Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In the Heart of Boston Stunning Waterfront Location

IN THE HEART OF BOSTON STUNNING WATERFRONT LOCATION OWNED BY CSREFI INDEPENDENCE WHARF BOSTON INC. independence wharf 470 atlantic avenue • Boston, MA Combining a Financial District address with a waterfront location and unparalleled harbor views, Independence Wharf offers tenants statement-making, first-class office space in a landmark property in downtown Boston. The property is institutionally owned by CSREFI INDEPENDENCE WHARF BOSTON INC., a Delaware Corporation, which is wholly owned by the Credit Suisse Real Estate Fund International. Designed to take advantage of its unique location on the historic Fort Point Channel, the building has extremely generous window lines that provide tenants with breathtaking water and sky line views and spaces flooded with natural light. Independence Wharf’s inviting entrance connects to the Harborwalk, a publicly accessible wharf and walkway that provides easy pedestrian access to the harbor and all its attractions and amenities. Amenities abound inside the building as well, including “Best of Class” property management services, on-site conference center and public function space, on-site parking, state-of-the-art technical capabilities, and a top-notch valet service. OM R R C AR URPHY o HE R C N HI IS CI ASNEY el CT ST v LL R TI AL ST CT L De ST ESTO ST THAT CHER AY N N. ST WY Thomas P. O’Neill CA NORTH END CLAR ST BENN K NA ST E Union Wharf L T Federal Building CAUSEW N N WASH ET D ST MA LY P I ST C T NN RG FR O IE T IN T ND ST ST S FL IN PR PO ST T EE IN T RT GT CE ST LAND ST P ON OPER ST ST CO -

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 NANTUCKET HISTORIC DISTRICT Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: Nantucket Historic District Other Name/Site Number: 2. LOCATION Street & Number: Not for publication: City/Town: Nantucket Vicinity: State: MA County: Nantucket Code: 019 Zip Code: 02554, 02564, 02584 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: X Building(s): Public-Local: X District: X Public-State: Site: Public-Federal: Structure: Object: Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 5,027 6,686 buildings sites structures objects 5,027 6,686 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 13,188 Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: N/A NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 NANTUCKET HISTORIC DISTRICT Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this ____ nomination ____ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property ____ meets ____ does not meet the National Register Criteria. Signature of Certifying Official Date State or Federal Agency and Bureau In my opinion, the property ____ meets ____ does not meet the National Register criteria. -

Ye Crown Coffee House : a Story of Old Boston

Close. V i * '3 M ZCjft& I (jib ^ Site of the Crown Coffee House and Fidelity Trust Co. Building in 1916 p Qlrnuin (Enflfet ifym&t A Story of Old Boston BY WALTER K. WATKINS l}l}S&?>Q 1 Published by HENDERSON & ROSS Boston 1916 \>\tf Copyright 1916 Henderson & Ross omuorft jfl In presenting this history of one of Boston's old taverns we not only give to the readers its ancient history but also show how the locality developed, at an early day, from the mudflats of the water front to a business section and within the last quarter century has become the center of a commercial district* This story of the site of the Fidelity Trust Company Building, once that of the Crown Coffee House, is from the manuscript history of "Old Boston Taverns * 'pre- paredby Mr. W. K. Watkins. Pictures andprints are from the collection of Henderson & Ross* Photographs by Paul J* Weber* M m mS m rfffrai "• fr*Ji ifca£5*:: State Street, with the Crown Coffee House Site in the middle background, 191ft The High Street from the Market Place ye Crown Coffee House N 1635 the High Street leading from the Market Place to the water, with its dozen of low thatched- roofed-houses was a great con- trast to the tall office buildings of State Street of today. One of the latest ocean steamers would have filled its length, ending as it did, in the early days, at the waterside where Mer- chants Row now extends. At the foot of the Townhouse Street as it was later called, when the townhouse was built on the site of the Old State House, was the Town's Way to the flats. -

Boston Harbor National Park Service Sites Alternative Transportation Systems Evaluation Report

U.S. Department of Transportation Boston Harbor National Park Service Research and Special Programs Sites Alternative Transportation Administration Systems Evaluation Report Final Report Prepared for: National Park Service Boston, Massachusetts Northeast Region Prepared by: John A. Volpe National Transportation Systems Center Cambridge, Massachusetts in association with Cambridge Systematics, Inc. Norris and Norris Architects Childs Engineering EG&G June 2001 Form Approved REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE OMB No. 0704-0188 The public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing the burden, to Department of Defense, Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports (0704-0188), 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302. Respondents should be aware that notwithstanding any other provision of law, no person shall be subject to any penalty for failing to comply with a collection of information if it does not display a currently valid OMB control number. PLEASE DO NOT RETURN YOUR FORM TO THE ABOVE ADDRESS. 1. REPORT DATE (DD-MM-YYYY) 2. REPORT TYPE 3. DATES COVERED (From - To) 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5a. CONTRACT NUMBER 5b. GRANT NUMBER 5c. PROGRAM ELEMENT NUMBER 6. AUTHOR(S) 5d. PROJECT NUMBER 5e. TASK NUMBER 5f. WORK UNIT NUMBER 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 8. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION REPORT NUMBER 9. SPONSORING/MONITORING AGENCY NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 10. -

State of the Park Report, Salem Maritime National Historic Site

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior STATE OF THE PARK REPORT Salem Maritime National Historic Site Salem, Massachusetts April 2013 National Park Service 2013 State of the Park Report for Salem Maritime National Historic Site State of the Park Series No. 7. National Park Service, Washington, D.C. On the cover: The tall ship, Friendship of Salem, the Custom House, Hawkes House, and historic wharves at Salem Maritime Na- tional Historic Site. (NPS) Disclaimer. This State of the Park report summarizes the current condition of park resources, visitor experience, and park infra- structure as assessed by a combination of available factual information and the expert opinion and professional judgment of park staff and subject matter experts. The internet version of this report provides the associated workshop summary report and additional details and sources of information about the findings summarized in the report, including references, accounts on the origin and quality of the data, and the methods and analytic approaches used in data collection and assessments of condition. This report provides evaluations of status and trends based on interpretation by NPS scientists and managers of both quantitative and non-quantitative assessments and observations. Future condition ratings may differ from findings in this report as new data and knowledge become available. The park superintendent approved the publication of this report. SALEM MARITIME NATIONAL HISTORIC SITE CONTENTS Executive Summary 1 State of the Park Summary Table 3 Summary of Stewardship Activities and Key Accomplishments to Maintain or Improve Priority Resource Condition: 5 Key Issues and Challenges for Consideration in Management Planning 6 Chapter 1. -

Inner Harbor Connector Ferry

Inner Harbor Connector Ferry Business Plan for New Water Transportation Service 1 2 Inner Harbor Connector Contents The Inner Harbor Connector 3 Overview 4 Why Ferries 5 Ferries Today 7 Existing Conditions 7 Best Practices 10 Comprehensive Study Process 13 Collecting Ideas 13 Forecasting Ridership 14 Narrowing the Dock List 15 Selecting Routes 16 Dock Locations and Conditions 19 Long Wharf North and Central (Downtown/North End) 21 Lewis Mall (East Boston) 23 Navy Yard Pier 4 (Charlestown) 25 Fan Pier (Seaport) 27 Dock Improvement Recommendations 31 Long Wharf North and Central (Downtown/North End) 33 Lewis Mall (East Boston) 34 Navy Yard Pier 4 (Charlestown) 35 Fan Pier (Seaport) 36 Route Configuration and Schedule 39 Vessel Recommendations 41 Vessel Design and Power 41 Cost Estimates 42 Zero Emissions Alternative 43 Ridership and Fares 45 Multi-modal Sensitivity 47 Finances 51 Overview 51 Pro Forma 52 Assumptions 53 Funding Opportunities 55 Emissions Impact 59 Implementation 63 Appendix 65 1 Proposed route of the Inner Harbor Connector ferry 2 Inner Harbor Connector The Inner Harbor Connector Authority (MBTA) ferry service between Charlestown and Long Wharf, it should be noted that the plans do not specify There is an opportunity to expand the existing or require that the new service be operated by a state entity. ferry service between Charlestown and downtown Massachusetts Department of Transportation (MassDOT) Boston to also serve East Boston and the South and the Massachusetts Port Authority (Massport) were Boston Seaport and connect multiple vibrant both among the funders of this study and hope to work in neighborhoods around Boston Harbor. -

Faneuil Hall Marketplace Office Space

FANEUIL HALL MARKETPLACE OFFICE SPACE HISTORIC LOCATION MEETS COOL, CREATIVE, BRICK & BEAM OFFICE SPACE SPEC SUITES AVAILABLE vision planvision illustrative faneuil hall marketplace – vision plan overview – vision marketplace hall faneuil AVAILABLE TO PARK STREET, STATE STREET, & DOWNTOWN CROSSING SPACE FANEUIL HALL AMENITIES NORTH STREET faneuil hall faneuil north street 7 5 SOUTH MARKET BUILDING STATE NEW YORK STREET DELI PARKING 5th floor 7,048 RSF GREEK 13,036 RSF 5,988 RSF 6,155 RSF CUISINE 9,893 RSF 3,738 RSF New Spec Suites FOOD 1 COLONNADE 6 *Ability to assemble 32,000 +/- RSF of contiguous space north market south market quincy market 4th floor CHATHAM STREET CHATHAM CLINTON STREET chatham streetchatham 2 streetclinton 3,699 RSF 3,132 RSF sasaki | ashkenazy acquisition | acquisition sasaki | ashkenazy 1,701 RSF 7 1,384 RSF 851 RSF s market street market s QUINCY 836 RSF n market street market n MARKET 630 RSF 4 3rd floor 5,840 RSF 8 10,109 RSF 4,269 RSF elkus manfredi architects 3,404 RSF TO AQUARIUM & SOUTH NORTH 1,215 RSF ROSE F. KENNEDY TO HAYMARKET GREENWAY & NORTH STATION 805 RSF N BOSTON COMMON SEAPORT FINANCIAL DISTRICT DOWNTOWN CROSSING 7- MINU TE W ALK STATE STREET GOVERNMENT CENTER ROSE KENNEDY GREENWAY 2-MINUTE WALK SOUTH MARKET LONG WHARF NORTH FERRY TO THE SOUTH SHORE ALTCORK1002 Date: 6/17/11 Version : 1 Page: 1 ALTCORK1002_T Shirt PE back NA JHavens New Balance PE 4.25” x 3.9” NA Anthony Shea SJuselius NA NA SJuselius 617.587.8675 NA CMYK 4.25” x 3.9” grphc prints 1.25” from collar on back. -

Getting a Dose of Boston History While Dining Everybody Loves A

Getting a Dose of Boston History While Dining Everybody loves a good meal, but sometimes that’s just not enough. For those of you who would like a dose of history with your dinner, Boston is the ideal place to get just the right mix. Here are some of the top choices, although there are many more as well. Boston’s Old City Hall, built in 1865 in the French Second Empire Style, is the home of the Ruth’s Chris Steak House. On the way in, check out Ben Franklin’s Statue, which is where the first public school in America was built. Hence, the address of 45 School Street. The Old City Hall is just across the street from The Omni Parker House, which was where visiting dignitaries would stay. It was Boston’s first hotel and opened in 1855. No discussion of famous Boston restaurants would be complete without noting Parker’s Restaurant at The Omni Parker House, where Parker House Rolls and Boston Crème Pie were invented. 60 School Street. The Chart House is housed in Boston’s oldest wharf building (circa 1760) and is known as The Gardiner Building. It once housed the offices of John Hancock and was known as John Hancock’s Counting House. Located at 60 Long Wharf, just behind the Marriott Long Wharf Hotel. Perhaps the most famous restaurant in town is The Union Oyster House, which was established in 1826 and claims to be America's oldest restaurant. The building itself, located a few steps from Faneuil Hall, is even more long-standing and has served as a local landmark for over 250 years. -

Who Was Jack Tar?: Aspects of the Social History of Boston, Massachusetts Seamen, 1700-1770

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1972 Who Was Jack Tar?: Aspects of the Social History of Boston, Massachusetts Seamen, 1700-1770 Clark Joseph Strickland College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Strickland, Clark Joseph, "Who Was Jack Tar?: Aspects of the Social History of Boston, Massachusetts Seamen, 1700-1770" (1972). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539624780. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-v75p-nz66 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WHO WAS JACK TAR? ASPECTS OF THE SOCIAL HISTORY OF BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS SEAMEN, 1700 - 1770 A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Clark J. Strickland 1972 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of f.hoV*A W *Y»onn ViA 1 AT*omon WAMVA* +*VW <s f* AyV A +•V A4VIac» V4 ^ OW f Master of Arts Clark J, Strickland Author Approved, July 1972 Richard Maxwell Brown PhilipsJ U Funigiello J oj Se ii 5 8 5 2 7 3 Cojk TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ABSTRACT........................................... iv CHAPTER I. -

Mepa Environmental Notification Form

ENVIRONMENTAL NOTIFICATION FORM The Pinnacle at Central Wharf Submitted to: Executive Office of Energy & Environmental Affairs MEPA Office 100 Cambridge Street, Suite 900 Boston, MA 02114 Submitted by: RHDC 70 East India LLC c/o The Chiofaro Company One International Place Boston, MA 02110 Prepared by: Epsilon Associates, Inc. 3 Mill & Main Place, Suite 250 Maynard, MA 01754 In Association with: Copley Wolff Design Group Cosentini Associates DLA Piper LLP (US) Haley and Aldrich Howard Stein Hudson Kohn Pedersen Fox Associates PC McNamara Salvia Nitsch Engineering July 15, 2020 July 15, 2020 PRINCIPALS Subject: The Pinnacle at Central Wharf Theodore A Barten, PE Environmental Notification Form Margaret B Briggs Massachusetts Environmental Policy Act (MEPA) Dale T Raczynski, PE Cindy Schlessinger Dear Interested Party: Lester B Smith, Jr Robert D O’Neal, CCM, INCE On behalf of the Proponent, RHDC 70 East India LLC, I am pleased to send you the Michael D Howard, PWS enclosed Environmental Notification Form (ENF) for the redevelopment of the 1.32-acre Douglas J Kelleher Boston Harbor Garage site in Boston’s Downtown Waterfront District. The project is AJ Jablonowski, PE located at 70 East India Row (a/k/a 270 Atlantic Avenue) in the City of Boston. Stephen H Slocomb, PE The Proponent expects that the ENF will be noticed in the Environmental Monitor on July David E Hewett, LEED AP 22, 2020 and that comments will be due by August 11, 2020. Comments can be submitted Dwight R Dunk, LPD online at: David C Klinch, PWS, PMP Maria B Hartnett https://eeaonline.eea.state.ma.us/EEA/PublicComment/Landing/ or sent to: ASSOCIATES Secretary Kathleen A. -

Boston Nps Map A5282872-8D05

t t E S S G t t B S B d u t D t a n n I S r S r k t l t e e R North S l o r e s To 95 t e o t c H B l o t m i t S m t S n l f b t t n l a le h S S u S u R t c o o t s a S n t E n S C T a R m n t o g V e u l S I s U D e M n n R l s E t M i e o F B V o e T p r s S n x e in t t P p s u r e l h H i L m e r u S C IE G o a S i u I C h u q e L t n n r R E L P H r r u n o T a i el a t S S k e S 1 R S w t gh C r S re t t 0 R 0 0.1 Kilometer 0.3 F t S t e M S Y a n t O r r E e M d u M k t t T R Phipps n S a S S e r H H l c i t Bunker Hill em a Forge Shop V D e l n t C o i o d S nt ll I 0 0.1 Mile 0.3 Street o o Monument S w h o n t e P R c e P S p Cemetery S W e M t IE S o M r o e R Bunker Hill t r t n o v C A t u R A s G S m t s y 9 C S h p a V e t q e t Community u n V I e e s E W THOMPSON S a t W 1 r e e s c y T s College e t r t e SQUARE i S v n n n d t Gate 4 t o S S P r A u w Y n S W t o i IE t a t n t o a lla L e R W c 5 S s t n e Boston Marine Society M C C S t i y n e t t o 8 r a a y h a r t e f e e e m t S L in t re l l A S o S S u C t S a em n P m o d t Massachusetts f h t w S S n a 1 i COMMUNITY u o t m S p r n S s h b e Commandant’s Korean War o M S i u COLLEGE t n t S t p S O S t b il c M TRAIN ING FIELD House Veterans Memorial d R l e D u d i n C R il n ti W p P t d s R o o S Y g u a u m u d USS Constitution i A sh t M r o D n W O in on h t th m t o SHIPYARD g g i er s S a n n lw Museum O P a M n i o a l W t U f n t n i E C PARK y B O Ly o o e n IE s n r v S t m D K a n H W d R N d e S S R y 2 S e t 2 a t 7 s R IG D t Y r Building -

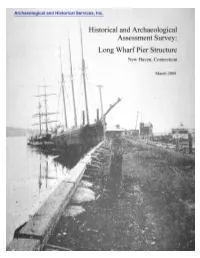

Long Wharf\Report.Wpd

REPORT: HISTORICAL AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT SURVEY LONG WHARF PIER STRUCTURE NEW HAVEN, CONNECTICUT Prepared for Parsons Brinckerhoff Quade & Douglas, Inc. March 2008 Archaeological and Historical Services, Inc. Author: Bruce Clouette 569 Middle Turnpike P.O. Box 543 Storrs, CT 06268 (860) 429-2142 voice (860) 429-9454 fax [email protected] REPORT: HISTORICAL AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT SURVEY LONG WHARF PIER STRUCTURE NEW HAVEN, CONNECTICUT Prepared for Parsons Brinckerhoff Quade & Douglas, Inc. March 2008 Archaeological and Historical Services, Inc. Author: Bruce Clouette 569 Middle Turnpike P.O. Box 543 Storrs, CT 06268 (860) 429-2142 voice (860) 429-9454 fax [email protected] ABSTRACT/MANAGEMENT SUMMARY In connection with environmental review studies of proposed I-95 improvements, the Connecticut State Historic Preservation Office (SHPO) in August 2007 requested “information regarding the historic use, development chronology, and archaeological integrity of the Long Wharf pier structure” in New Haven, Connecticut. Extending approximately 650 feet into New Haven harbor, the wharf is the home berth of the schooner Amistad. This report, prepared by Archaeological and Historical Services, Inc. of Storrs, Connecticut, presents in detail the information about the structure that was requested by the SHPO. In its present form, Long Wharf is a concrete slab and riprap structure that was created in the early 1960s in connection with a massive urban renewal project. The base of the modern wharf, however, is a stone and earth-fill structure built in 1810 by William Lanson, a prominent and sometimes controversial member of New Haven’s African American community. That structure was a 1,500-foot extension of an 18th-century timber wharf, making the whole, at some 3,900 feet, the longest wharf in the country at the time.