The Weak Neutral Current Arxiv:1303.5522V1 [Hep-Ph]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

12 from Neutral Currents to Weak Vector Bosons

12 From neutral currents to weak vector bosons The unification of weak and electromagnetic interactions, 1973{1987 Fermi's theory of weak interactions survived nearly unaltered over the years. Its basic structure was slightly modified by the addition of Gamow-Teller terms and finally by the determination of the V-A form, but its essence as a four fermion interaction remained. Fermi's original insight was based on the analogy with elec- tromagnetism; from the start it was clear that there might be vector particles transmitting the weak force the way the photon transmits the electromagnetic force. Since the weak interaction was of short range, the vector particle would have to be heavy, and since beta decay changed nuclear charge, the particle would have to carry charge. The weak (or W) boson was the object of many searches. No evidence of the W boson was found in the mass region up to 20 GeV. The V-A theory, which was equivalent to a theory with a very heavy W , was a satisfactory description of all weak interaction data. Nevertheless, it was clear that the theory was not complete. As described in Chapter 6, it predicted cross sections at very high energies that violated unitarity, the basic principle that says that the probability for an individual process to occur must be less than or equal to unity. A consequence of unitarity is that the total cross section for a process with 2 angular momentum J can never exceed 4π(2J + 1)=pcm. However, we have seen that neutrino cross sections grow linearly with increasing center of mass energy. -

Discovery of Weak Neutral Currents∗

Discovery of Weak Neutral Currents∗ Dieter Haidt Emeritus at DESY, Hamburg 1 Introduction Following the tradition of previous Neutrino Conferences the opening talk is devoted to a historic event, this year to the epoch-making discovery of Weak Neutral Currents four decades ago. The major laboratories joined in a worldwide effort to investigate this new phenomenon. It resulted in new accelerators and colliders pushing the energy frontier from the GeV to the TeV regime and led to the development of new, almost bubble chamber like, general purpose detectors. While the Gargamelle collaboration consisted of seven european laboratories and was with nearly 60 members one of the biggest collaborations at the time, the LHC collaborations by now have grown to 3000 members coming from all parts in the world. Indeed, High Energy Physics is now done on a worldwide level thanks to net working and fast communications. It seems hardly imaginable that 40 years ago there was no handy, no world wide web, no laptop, no email and program codes had to be punched on cards. Before describing the discovery of weak neutral currents as such and the cir- cumstances how it came about a brief look at the past four decades is anticipated. The history of weak neutral currents has been told in numerous reviews and spe- cialized conferences. Neutral currents have since long a firm place in textbooks. The literature is correspondingly rich - just to point out a few references [1, 2, 3, 4]. 2 Four decades Figure 1 sketches the glorious electroweak way originating in the discovery of weak neutral currents by the Gargamelle Collaboration and followed by the series of eminent discoveries. -

Introduction to Subatomic- Particle Spectrometers∗

IIT-CAPP-15/2 Introduction to Subatomic- Particle Spectrometers∗ Daniel M. Kaplan Illinois Institute of Technology Chicago, IL 60616 Charles E. Lane Drexel University Philadelphia, PA 19104 Kenneth S. Nelsony University of Virginia Charlottesville, VA 22901 Abstract An introductory review, suitable for the beginning student of high-energy physics or professionals from other fields who may desire familiarity with subatomic-particle detection techniques. Subatomic-particle fundamentals and the basics of particle in- teractions with matter are summarized, after which we review particle detectors. We conclude with three examples that illustrate the variety of subatomic-particle spectrom- eters and exemplify the combined use of several detection techniques to characterize interaction events more-or-less completely. arXiv:physics/9805026v3 [physics.ins-det] 17 Jul 2015 ∗To appear in the Wiley Encyclopedia of Electrical and Electronics Engineering. yNow at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, Laurel, MD 20723. 1 Contents 1 Introduction 5 2 Overview of Subatomic Particles 5 2.1 Leptons, Hadrons, Gauge and Higgs Bosons . 5 2.2 Neutrinos . 6 2.3 Quarks . 8 3 Overview of Particle Detection 9 3.1 Position Measurement: Hodoscopes and Telescopes . 9 3.2 Momentum and Energy Measurement . 9 3.2.1 Magnetic Spectrometry . 9 3.2.2 Calorimeters . 10 3.3 Particle Identification . 10 3.3.1 Calorimetric Electron (and Photon) Identification . 10 3.3.2 Muon Identification . 11 3.3.3 Time of Flight and Ionization . 11 3.3.4 Cherenkov Detectors . 11 3.3.5 Transition-Radiation Detectors . 12 3.4 Neutrino Detection . 12 3.4.1 Reactor Neutrinos . 12 3.4.2 Detection of High Energy Neutrinos . -

The Weak Charge of the Proton Via Parity Violating Electron Scattering

The Weak Charge of the Proton via Parity Violating Electron Scattering Dave “Dawei” Mack (TJNAF) SPIN2014 Beijing, China Oct 20, 2014 DOE, NSF, NSERC SPIN2014 All Spin Measurements Single Spin Asymmetries PV You are here … … where experiments are unusually difficult, but we don’t annoy everyone by publishing frequently. 2 Motivation 3 The Standard Model (a great achievement, but not a theory of everything) Too many free parameters (masses, mixing angles, etc.). No explanation for the 3 generations of leptons, etc. Not enough CP violation to get from the Big Bang to today’s world No gravity. (dominates dynamics at planetary scales) No dark matter. (essential for understanding galactic-scale dynamics) No dark energy. (essential for understanding expansion of the universe) What we call the SM is only +gravity part of a larger model. +dark matter +dark energy The astrophysical observations are compelling, but only hint at the nature of dark matter and energy. We can look but not touch! To extend the SM, we need more BSM evidence (or tight constraints) from controlled experiments4 . The Quark Weak Vector Charges p Qw is the neutral-weak analog of the proton’s electric charge Note the traditional roles of the proton and neutron are almost reversed: ie, neutron weak charge is dominant, proton weak charge is almost zero. This suppression of the proton weak charge in the SM makes it a sensitive way to: 2 •measure sin θW at low energies, and •search for evidence of new PV interactions between electrons and light quarks. 5 2 Running of sin θW 2 But sin θW is determined much better at the Z pole. -

Measurement of Neutrino-Nucleon Neutral-Current Elastic Scattering Cross-Section at Sciboone

Measurement of Neutrino-Nucleon Neutral-Current Elastic Scattering Cross-section at SciBooNE Hideyuki Takei Thesis submitted to the Department of Physics in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Science at Tokyo Institute of Technology February, 2009 2 Abstract In this thesis, results of neutrino-nucleon neutral current (NC) elastic scattering analysis are presented. Neutrinos interact with other particles only with weak force. Measure- ment of cross-section for neutrino-nucleon reactions at various neutrino en- ergy are important for the study of nucleon structure. It also provides data to be used for beam flux monitor in neutrino oscillation experiments. The cross-section for neutrino-nucleon NC elastic scattering contains the 2 axial vector form factor GA(Q ) as well as electromagnetic form factors unlike electromagnetic interaction. GA is propotional to strange part of nucleon spin (∆ s) in Q2 → 0 limit. Measurement of NC elastic cross-section with smaller Q2 enables us to access ∆ s. NC elastic cross-sections of neutrino- nucleon and antineutrino-nucleon were measured earlier by E734 experiment at Brookheaven National Laboratory (BNL) in 1987. In this experiment, cross-sections were measured in Q2 > 0.4 GeV 2 region. Result from this experiment was the only published data for NC elastic scattering cross-section published before our experiment. SciBooNE is an experiment for the measurement of neutrino-nucleon scat- tering cross-secitons using Booster Neutrino Beam (BNB) at FNAL. BNB has energy peak at 0.7 GeV. In this energy region, NC elastic scattering, charged current elastic scattering, charged current pion production, and neutral cur- rent pion production are the major reaction branches. -

1989-1990 Eight College Teachers Participated in the Training

SATYENDRA NATH BOSE NATIONAL CENTRE FOR BASIC SCIENCES Calcutta ANNUAL REPORT April 1, 1989 to March 31,1990 Objectives The objectives of the S N Bose National Centre for Basic Sciences established in June 1986 as a registered society functioning under the umbrella of the Department of Science & Technology, Government of India, are : To foster, encourage and promote the growth of advanced studies in selected branches of basic sciences ; To conduct original research in theoretical and mathematical sciences and other basic sciences in frontier areas, including challenging theoretical studies of future applications ; To provide a forum of personal contacts and intellectual interaction among scientists within the country and also between them and scientists abroad ; To train young scientists for research in basic sciences. Governing Body The present Governing Body of the Centre consists of the following members : 1 Dr V Gowariker Secretary Chairman Department of Science & Technology Government of India, New Delhi 2 Professor C N R Rao Direct or Member Indian Institute of Science Bangalore 3 Professor C S Seshadri Dean Member School of Mathematics SPIC, Science Foundation Madras Professor J V Narlikar Director Member Inter-Universit y Centre for Astronomy & Astrophysics Pune Shri B K Chaturvedi Joint Secretary & Financial Adviser Member Department of Science & Technology Government of India, New Delhi Shri T C Dutt Chief Secretary Member Government of West Bengal Calcutta Professor C K Mzjumdar Director Member S N Bose National Centre for Basic Sciences Calcutta Dr J Pal Chaud huri Administrative Officer Non-member-Secretary S N Bose National Centre for Basic Sciences Calcutta At the moment the Centre operates from a rented house located at DB 17, Sector I, Salt Lake City, Calcutta 700 064. -

TRIUMF & Canadian Scientists Help Measure Proton's Weak Charge

Canada’s national laboratory for particle and nuclear physics Laboratoire national canadien pour la recherche en physique nucléaire et en physique des particules News Release | For Immediate Release | 17 Sep 2013, 5:00 p.m. PDT TRIUMF & Canadian Scientists Help Measure Proton’s Weak Charge (Newport News, VA, USA) --- An international team including Canadian researchers at TRIUMF has reported first results for the proton’s weak charge in Physical Review Letters (to appear in the October 18, 2013 issue) based on precise new data from Jefferson Laboratory, the premier U.S. electron-beam facility for nuclear and particle physics in Newport News, Virginia. The Q-weak experiment used a high-energy electron beam to measure the weak charge of the proton—a fundamental property that sets the scale of its interactions via the weak nuclear force. This is distinct from but analogous to its more familiar electric charge (Q), hence, the experiment’s name: ‘Q-weak.’ Following a decade of design and construction, Q-weak had a successful experimental run in 2010–12 in Hall C at Jefferson Laboratory. Data analysis has been underway ever since. “Nobody has ever attempted a measurement of the proton’s weak charge before,” says Roger Carlini, Q- weak’s spokesperson at Jefferson Laboratory, “due to the extreme technical challenges to reach the required sensitivity. The first 4% of the data have now been fully analyzed and already have an important scientific impact, although the ultimate sensitivity awaits analysis of the complete experiment.” The first result, based on Q-weak’s commissioning data set, is Q_W^p= 0.064 ± 0.012. -

Neutrino Masses-How to Add Them to the Standard Model

he Oscillating Neutrino The Oscillating Neutrino of spatial coordinates) has the property of interchanging the two states eR and eL. Neutrino Masses What about the neutrino? The right-handed neutrino has never been observed, How to add them to the Standard Model and it is not known whether that particle state and the left-handed antineutrino c exist. In the Standard Model, the field ne , which would create those states, is not Stuart Raby and Richard Slansky included. Instead, the neutrino is associated with only two types of ripples (particle states) and is defined by a single field ne: n annihilates a left-handed electron neutrino n or creates a right-handed he Standard Model includes a set of particles—the quarks and leptons e eL electron antineutrino n . —and their interactions. The quarks and leptons are spin-1/2 particles, or weR fermions. They fall into three families that differ only in the masses of the T The left-handed electron neutrino has fermion number N = +1, and the right- member particles. The origin of those masses is one of the greatest unsolved handed electron antineutrino has fermion number N = 21. This description of the mysteries of particle physics. The greatest success of the Standard Model is the neutrino is not invariant under the parity operation. Parity interchanges left-handed description of the forces of nature in terms of local symmetries. The three families and right-handed particles, but we just said that, in the Standard Model, the right- of quarks and leptons transform identically under these local symmetries, and thus handed neutrino does not exist. -

Cross Sections for Neutral-Current Neutrino-Nucleus Interactions: Applications for 12C and 16O

PHYSICAL REVIEW C VOLUME 59, NUMBER 6 JUNE 1999 Cross sections for neutral-current neutrino-nucleus interactions: Applications for 12C and 16O N. Jachowicz,* S. Rombouts, K. Heyde,† and J. Ryckebusch Institute for Theoretical Physics, Vakgroep Subatomaire en Stralingsfysica, Proeftuinstraat 86, B-9000 Gent, Belgium ~Received 29 September 1998; revised manuscipt received 4 February 1999! We study quasielastic neutrino-nucleus scattering on 12C and 16O within a continuum random phase ap- proximation ~RPA! model. The RPA equations are solved using a Green’s function approach with an effective Skyrme ~SkE2! two-body interaction. Besides a comparison with existing calculations, we carry out a detailed study using various methods ~Tamm-Dancoff approximation and RPA! and different forces ~SkE2 and Landau- Migdal!. We evaluate cross sections that may be relevant for neutrino nucleosynthesis. @S0556-2813~99!01606-4# PACS number~s!: 25.30.Pt, 24.10.Eq, 26.30.1k I. INTRODUCTION function approach in which the polarization propagator is approximated by an iteration of the first-order contribution Neutrinos are extremely well-suited probes to provide de- @14#. The unperturbed wave functions are generated using tailed information about the structure and properties of the either a Woods-Saxon potential or a HF calculation using a weak interaction, as they are only interacting via the weak Skyrme force. The latter approach makes self-consistent HF- forces. Moreover, being intrinsically polarized and coupling RPA calculations possible. Calculations using either a to the axial vector as well as to the vector part of the had- Skyrme or a Landau-Migdal force must give indications ronic current, neutrinos are able to reveal other and more about possible differences and sensitivity in methods to the precise nuclear structure information than, e.g., electrons do. -

The Search for Supersymmetry

The Search for Supersymmetry • Introduction the Standard Model of Particle Physics • Introduction to Collider Physics • Successes of the Standard Model • What the Standard Model Does Not Do • Physics Beyond the Standard Model • Introduction to Supersymmetry • Searching for Supersymmetry • Dark Matter Searches • Future Prospects • Other Scenarios • Summary Peter Krieger, Carleton University, August 2000 Force Unifications Standard Model does NOT account magnetism for gravitational interactions Maxwell electromagnetism electricity electroweak S T A Planck Scale (or Planck Mass) weak interactions N D A is defined as the energy scale at R GUT D which gravitational interactions M O become of the same strength as D E SM interactions strong interactions L TOE celestial movement gravitation Newton terrestrial movement - - - MEW MGUT Mplanck The Standard Model Describes the FUNDAMENTAL PARTICLES and their INTERACTIONS All known FORCES are mediated by PARTICLE EXCHANGE a a Effective strength of an interaction depends on X • the coupling strength at the vertex αα • the mass of the exchanged particle MX a a Force Effective Strength Process Strong 100 Nuclear binding Electromagnetic 10-2 Electron-nucleus binding Weak 10-5 Radioactive β decay The Standard Model SPIN-½ MATTER PARTICLES interact via the exchange of SPIN-1 BOSONS MATTER PARTICLES – three generations of quarks and leptons |Q| m < m < m ⎛ e ⎞ ⎛ µ ⎞ ⎛ τ ⎞ 1 e µ τ Mass increases with generation: ⎜ ⎟ ⎜ ⎟ ⎜ ⎟ m = 0 ⎜ ⎟ ⎜ν ⎟ ⎜ ⎟ ν ⎝ν e ⎠ ⎝ µ ⎠ ⎝ν τ ⎠ 0 Mu,d ~ 0.3 GeV ⎛u⎞ ⎛c⎞ ⎛ t ⎞ 2 ⎜ ⎟ ⎜ ⎟ ⎜ ⎟ 3 Each quark comes in 1 three ‘colour’ changes Mt ~ 170 GeV ⎝d⎠ ⎝s⎠ ⎝b⎠ 3 GAUGE BOSONS – mediate the interaction of the fundamental fermions γ 1 Gauge particle of electromagnetism (carries no electric charge) W ± ,Z 0 3 Gauge particles of the weak interaction (each carries weak charge) g 8 Gauge particles of the strong interaction (each gluon carries a colour and an anti-colour charge charge) All Standard Model fermions and gauge bosons have been experimentally observed There is one more particle in the SM – the Higgs Boson. -

How the First Neutral-Current Experiments Ended

How the first neutral-current experiments ended Peter Galison Lyman Laboratory of Physics, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138 At the beginning of the 1970s there seemed little reason to believe that strangeness-conserving neutral currents existed: theoreticians had no pressing need for them and several experiments suggested that they were suppressed if they were present at all. Indeed the two remarkable neutrino experiments that eventual- ly led to their discovery were designed and built for very different purposes, including the search for the vector boson and the investigation of the parton model. In retrospect we know that certain gauge theories (notably the Weinberg-Salam model) predicted that neutral currents exist. But until 't Hooft and Veltman proved that such theories were renormalizable, little effort was made to test the new theories. After the proof the two experimental groups began to reorient their goals to settle an increasingly central issue of physics. Do neutral currents exist? We ask here: What kind of evidence and arguments persuaded the par- ticipants that they had before them a real effect and not an artifact of the apparatus~ What eventually con- vinced them that their experiment was over? An answer to these questions requires an examination of the organization of the experiments, the nature of the apparatus, and the previous work of the experimentalists. Finally, some general observations are made about the recent evolution of experimental physics. CONTENTS weak interaction. Certainly the provisional advance af- I. Introduction 477 forded by such a move had many historical precedents. A II. The Experiment "Cxargamelle": from W Search to hundred years earlier Ampere unravelled many of the Neutral-Current Test 481 laws of electrodynamics by studying the interactions of III. -

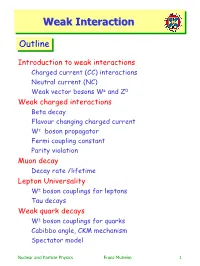

Weak Interactioninteraction

WeakWeak InteractionInteraction OutlineOutline Introduction to weak interactions Charged current (CC) interactions Neutral current (NC) Weak vector bosons W± and Z0 Weak charged interactions Beta decay Flavour changing charged current W± boson propagator Fermi coupling constant Parity violation Muon decay Decay rate /lifetime Lepton Universality W± boson couplings for leptons Tau decays Weak quark decays W± boson couplings for quarks Cabibbo angle, CKM mechanism Spectator model Nuclear and Particle Physics Franz Muheim 1 IntroductionIntroduction Weak Interactions Account for large variety of physical processes Muon and Tau decays, Neutrino interactions Decays of lightest mesons and baryons Z0 and W± boson production at √s ~ O(100 GeV) Natural radioactivity, fission, fusion (sun) Major Characteristics Long lifetimes Small cross sections (not always) “Quantum Flavour Dynamics” Charged Current (CC) Neutral Current (NC) mediated by exchange of W± boson Z0 boson Intermediate vector bosons MW = 80.4 GeV ± 0 W and Z have mass MZ = 91.2 GeV Self Interactions of W± and Z0 also W± and γ Nuclear and Particle Physics Franz Muheim 2 BetaBeta DecayDecay Weak Nuclear Decays See also Nuclear Physics Recall β+ = e+ β- = e- Continuous energy spectrum of e- or e+ Î 3-body decay, Pauli postulates neutrino, 1930 Interpretation Fermi, 1932 Bound n or p decay − n → pe ν e ⎛ − t ⎞ N(t) = N(0)exp⎜ ⎟ ⎝ τ n ⎠ p → ne +ν (bound p) τ n = 885.7 ± 0.8 s e 32 τ 1 = τ n ln 2 = 613.9 ± 0.6 s τ p > 10 y (p stable) 2 Modern quark level picture Weak charged current mediated