First Things First

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Budget Profile

2020-2021 Budget Profile Kansas City Kansas Public Schools School Finance Kansas State Department of Education Landon State Office Building 900 SW Jackson Street, Suite 356 Topeka, Kansas 66612-1212 www.ksde.org • Budget General Information (characteristics of district) • Supplemental Information for Tables in Summary of Expenditures • KSDE Website Information Available • Summary of Expenditures (Sumexpen.xlsx) i 20120-21 Budget General Information USD #: 500 Introduction The Kansas City, Kansas Public Schools (KCKPS) is a nationally recognized urban school district that serves approximately 22,000 students. With a Head Start program, four preschools, 29 elementary schools, 7 middle schools, and 5 high schools, the district serves a wonderfully diverse mixture of students. About 63 different languages are spoken in the homes of our students. To serve those students, the district employs approximately 4,000 staff. The vision of the Kansas City, Kansas Public Schools is to be one of the Top 10 school districts in the nation. Our goal is that “Each student will exit high school prepared for college and careers in a global society, and at every level, performance is on track and on time for success.” To help our students achieve this goal, the district has implemented a district-wide initiative called Diploma+. The goal of Diploma+ is for each student to graduate with a high school diploma plus one of the following seven endorsements: Completion of one year of college; Completion of an Industry-Recognized Certificate or Credential; Achievement of at least 21 on the ACT or 1060 on the SAT; Completion of an IB Diploma Programme or Career-Related Programme; Acceptance into the Military; Completion of a Qualified Internship or Industry-Approved Project; An Approved Plan for Post-Secondary Transition. -

Construction Progress Updates

fall 2018 CONSTRUCTION PROGRESS UPDATES TEACH IN KCKPS WHILE EARNING YOUR MASTER’S IN EDUCATION KCKPS TEACHERS OF THE YEAR HONORED AT ANNUAL KSDE BANQUET 2010 N. 59th St., Kansas City, KS 66104 KS City, Kansas St., 59th N. 2010 Kansas City, Kansas Public Schools Public Kansas City, Kansas EDUCATION CONNECTION — FALL 2018 1 IN THIS ISSUE Superintendent’s Message 3 Education Connection is a quarterly newsmagazine of the Kansas City, Kansas 4-5 Welcome Back Students Public Schools (KCKPS). Editorial copy and photography are created by the KCKPS 6 Students Have an Opportunity to Communications Department and produced Earn a Degree in 3 Years at the KU by NPG Newspapers. To receive a copy of Edwards Campus the magazine, call (913) 279-2242. A Spanish translation of the stories included in Education Connection is available on the district’s website Diploma+ 7 at kckps.org. 8-9 Construction Progress Updates Kansas City, Kansas Public Schools Central Offi ce and Training Center 10 KCKPS Honored as a Best Company 2010 N. 59th St. to Work For Kansas City, KS 66104 (913) 551-3200 www.kckps.org 10 Budget Approved for 2018-2019 School Year Superintendent of Schools Dr. Charles Foust Congratulations to Our Teachers 11 Director of Communications & Marketing Melissa Fears District Calendar 12 Editor, Education Connection 12 Teach in KCKPS While Earning Your KCK Board of Education Master’s in Education Wanda Brownlee Paige Harold Brown Stay in the Know Maxine Drew 13 Janey Humphries Brenda C. Jones Dr. Valdenia Winn Dr. Stacy Yeager COMMUNICATIONS RESOURCES Website: kckps.org fall 2018 CONSTRUCTION Facebook: facebook.com/kckschools PROGRESS UPDATES Twitter: twitter.com/kckschools TEACH IN KCKPS Instagram: instagram.com/kckschools WHILE EARNING YOUR MASTER’S IN EDUCATION KCKPS TEACHERS KCKPS-TV: OF THE YEAR HONORED AT ANNUAL Channel 18 (on Spectrum) KSDE BANQUET Channel 145 (on Google Fiber) YouTube: youtube.com/KCKPSTV 66104 KS City, Kansas St., 59th N. -

Download This

NPS Form 10-900 f - 0MB No. 10024-0018 Oct. 1990 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A) Complete each item by marking V in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-9000a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property ___ ________ Historic name Lowell Elementary School Other name/site number 209-2820-1711 2. Location Street & number 1040 Orville Avenue D not for publication City or town Kansas City d vicinity State Kansas Code KS County Wyandotte Code WY Zip code 66102 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this ^ nomination n request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property does not meet the National Register criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant D natfonajfy D statewig>-E locally. -

History of the Kansas Speech Communication Association

/K HISTORY OF THE KANSAS SPEECH COMMUNICATION ASSOCIATION/ by JOSEPH PAUL GLOTZBACH A .A Cloud County Community College, 1976 B. S. E. Emporia State University, 1978 A THESIS submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS SPEECH KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 1989 Approved by: Major Professor AllEDfl 3D1T75 .T+ ^Lx:' TABLE OF CONTENTS Qj5(p CHAPTER PAGE 1. INTRODUCTION 1 2. A SHORT HISTORY OF KSCA 8 3. CURRICULUM 34 4. CERTIFICATION 52 5. CONCLUSION 69 SOURCES CONSULTED 74 APPENDICES A. OFFICERS 79 B. CALENDAR OF EVENTS 109 C. ANNUAL CONFERENCES 115 D. OUTSTANDING TEACHERS 119 E. CONSTITUTION 122 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to express my appreciation to Professor Charlie Griffin who helped me through this project and Professors Harold Nichols and Bill Schenck-Hamlin for their input into this project. I also wish to thank those members of the Kansas Speech Communication Association who have given me files and journals from which this information came and especially Pat Lowrance of Butler County Community College who planted the seeds of the idea for this thesis. My final and deepest appreciation goes to my wife, Carol, and children, Jeremy and Megan, who have patiently waited for me to finish this project and will once again find out what normal life can be like. J.P.G. CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION In 1987, Larry Laas, President of the Kansas Speech Communication Association and speech teacher at Satanta High School, in the executive meeting of the KSCA board, stressed the importance of establishing in the Association the position of Historian. -

On His Birthday, President Scott Martens Opened the Meeting

Lisa Terrell, Counselor, Bonner Springs Susan Wilson Yao, Counselor, Turner High School John Nguyen, Principal, Piper High School Polly Vader, Counselor, Piper High School Mary Kate Kelly, Counselor, Bishop Ward High School member Jay Dunlap, President, Bishop Ward High School Finally, a huge thank you to our members who served as judges for this week’s speech presentations, Karole Bradford, Hank Chamberlain, Terry Robinson, Jen Wewers, and Terry Websites: Club: www.rotarydowntownkck.org, District: www.rotary5710.org, International: www.rotary.org Woodbury. Volume 82 April 16, 2021 No. 42 NEXT WEEK AT ROTARY – We will host male students from several area high schools who will present to the Club in connection with LAST TUESDAY AT ROTARY – On his birthday, President Scott our annual Scholarship Competition. Terry Robinson is the Martens opened the meeting and led members in the Pledge of program chair for April. If you would be willing to serve as a Allegiance. Happy Birthday Scott!! Jay Dunlap provided the judge for next week’s student speeches, please contact invocation, focusing on faith, hope and love. We were also joined Rosemary Podrebarac. by a guest, Beverly Russell, who is the Director of Sales for the Hilton Garden Inn Kansas City, Kansas. ANNOUNCEMENTS: For Community Service opportunities, in honor of Earth Day Terry Robinson, program chair for the month of April, welcomed (April 22nd), the Club is undertaking some area Clean-up some talented young women from area high schools. Ken Davis Activities: served as master of ceremonies for the day, as these young women • Rosedale Clean-up: We have selected this Saturday, made presentations to the Club to be considered for a scholarship April 17, 2021, from 9 am -11 am, to clean up the Frank to be awarded. -

Comprehensive Economic Development Strategy Plan for Metropolitan Kansas City

Comprehensive Economic Development Strategy Plan for Metropolitan Kansas City Mid-America Regional Council Community Services Corporation 600 Broadway, Suite 200 | Kansas City, MO 64105 816-474-4240 | www.marc.org April 2014 MID-AMERICA REGIONAL COUNCIL Comprehensive Economic Development Strategy Plan 1 Mid-America Regional Council • 2014 Table of Contents Introduction ...........................................................................................................................................................3 Analyzing Greater Kansas City’s Economy ...............................................................................................4 Population Trends ........................................................................................................................................4 Employment ...................................................................................................................................................5 Industry Specialization ...............................................................................................................................8 Exports .............................................................................................................................................................11 Innovation and Entrepreneurship ..........................................................................................................12 Education and Workforce ........................................................................................................................13 -

2012 Annual Report.Indd

A Message From the to nurture more fruit orchards, community gardens, and to benefi t those in need in the Kansas City metropolitan area. Executive Director We are extremely grateful to all our supporters and collaborators for your contributions this year. Now more than KCCG is celebrating a successful ever, we need your support. From fi nancial contributions to and challenging year, as we innovative new ideas for transforming Kansas City’s food system fi nd ourselves transforming through urban gardening in the coming years, KCCG depends from a relatively small, grass- on your voices, your vision, and your investment in gardening roots nonprofi t organization to for Kansas City’s future. Thank you for making 2012 a landmark one with a greater vision and a year both for KCCG and for increased healthy food access in broader impact than ever before. Kansas City. As more and more commu- nity and backyard gardeners, Ben Sharda neighborhood groups, schools, Executive Director congregations, and others reach out to KCCG for support to grow their own healthy food, we fi nd that our agency expenses and staffi ng are also growing to keep pace with the needs of the community. The Greater Kansas City Food Policy Coalition reports that thousands of people in the metropolitan area are experi- Board of Directors encing food insecurity. Many of the households that KCCG serves are living in urban food deserts, without adequate Deandra Palmer President transportation to purchase healthy food. Gardening is a great Becky Johnston Vice President way to help families and neighborhoods improve nutrition Sarah Soard Secretary and increase access to fresh fruits and vegetables, while saving Vince Magers Treasurer money on food costs. -

Hundreds of Students Benefit from Diploma+ Scholarship Initiative

WINTER 2016 HUNDREDS OF STUDENTS BENEFIT FROM DIPLOMA+ SCHOLARSHIP INITIATIVE CYNTHIA LANE NAMED SUPERINTENDENT OF THE YEAR SCHOOL LIBRARIES REMAIN RELEVANT AND RESOURCEFUL IN TODAY’S TECH-SAVVY WORLD 2010 N. 59th St., Kansas City, KS 66104 KS City, Kansas St., 59th N. 2010 Kansas City, Kansas Public Schools Public Kansas City, Kansas EDUCATION CONNECTION — WINTER 2016 1 @V\)LSVUNH[2*2** :[HY[`V\YUL^`LHYUV^ ,UYVSSMVY1HU\HY`*SHZZLZ 4HPU*HTW\Z;LJOUPJHS,K\JH[PVU*LU[LY2*2**7PVULLY*LU[LYH[3LH]LU^VY[O ^^^RJRJJLK\HKTPZZ'RJRJJLK\ ¸(U,X\HS6WWVY[\UP[`,K\JH[PVUHS0UZ[P[\[PVU¹ 75050609 2 EDUCATION CONNECTION — WINTER 2016 MESSAGE FROM THE SUPERINTENDENT We live in a ensure KCKPS, and therefore the community, continues to excel and achieve. state where, if A key challenge in front of KCKPS (and all school you drive down districts) is to evolve our education system to meet the demands of our fast-moving global society. We almost any know that today, each student must have a solid rural road, you academic foundation, anchored by strong literacy skills, along with the work-ready skills required in will see barns professions of the future. One question we must that could continue to ask is: How do we transform the educa- tional experiences our students receive in a manner never have that will prepare them for the demands they will face been put up by in their futures? Forum participants grappled with this question, an individual even as they applauded the progress of the dis- Dr. Cynthia Lane working alone. trict. -

Kansas Preservation

Kansas Preservation Jan/Feb 2008 • Volume 30, No. 1 REAL PLACES. REAL STORIES. A Tale of Two Bridges See story on page 3. Newsletter of the Cultural Resources Division Kansas Historical Society Contents 2 A Tale of Two Bridges A New Look for a New Year 7 Nominations to the National Long-time readers will notice a new look for our award-winning, bimonthly Register of Historic Places newsletter. With this first issue of 2008, we are proud to introduce full color and 15 a new cover and layout design by our graphic designer, Linda Kunkle Park. New Opportunities for Historic We are excited about 2008, which will mark the 30th year of publication for Properties in Kansas Kansas Preservation. The first issue debuted in Autumn 1978 (sure to be worth a fortune today on eBay) and featured four fact-filled pages. The mission statement, 17 found on page 2, stated: “The purpose of this quarterly publication is to provide Be on the Lookout for the information on techniques, planning programs, projects, and related subjects to Past-O-Rama! assist Kansans in taking best advantage of their historic resources. We hope to 18 encourage the preservation and continuing use of the state’s architectural, 2008 KATP Field School historic, and cultural resources.” This purpose remains true today, although we have since added archeological resources to the list and increased our publication frequency. The first issue reported that the office had been renamed the Historic KANSAS PreserVatioN Preservation Department (previously known as Historic Sites Survey office). Published bimonthly by the Cultural Otherwise the topics were not dissimilar from today with articles on the Historic Resources Division, Kansas Historical Society, Sites Board of Review, the rehabilitation tax credit for National Register-listed 6425 SW 6th Avenue, Topeka KS 66615-1099. -

30Celebrating 30 Years of Giving

Celebrating 30 Years of Giving 3030More Giving, Smarter Investing, a Better Kansas City Vision Community dreams fulfilled through the power of philanthropy Mission To improve the quality of life in Greater Kansas City by increasing charitable giving, connecting donors to community needs they care about, and providing leadership on critical community issues Commitment to Diversity As the community’s foundation, we are committed to promoting equity and inclusion throughout the region we serve, and it is our obligation to model diversity and focus the community conversation on racial equity. “We make a living by what we get, we make a life by what we give.” SIR WINSTON CHURCHILL Introduction Thirty years ago, seven people who were passionate about making Kansas City a better place created what we now know to be the Greater Kansas ANNUAL REPORT 2007 City Community Foundation. The Community Foundation began when those seven individuals passed 3 INTRODUCTION a hat to collect a couple hundred dollars and some change. Now, more than 2,200 funds have joined our family of giving. By the end of 2007, 4 BOARD OF DIRECTORS our donors had given more than $1.25 billion to community causes in just three decades. 6 AFFILIATES If you want to give back to the place you call home, we encourage you 10 FINANCIALS to give us a call. We can help you do everything from organizing and automating your charitable giving to creating a giving plan that will last 17 DONOR STORIES for generations to come. 79 FUND LISTING We invite you to read through our annual report, which will give you a glimpse of the 30 years we have been serving people—just like you— 97 STAFF LISTING who want to make a difference. -

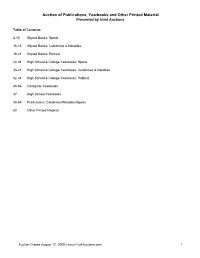

Augustfinalip Sorted

Auction of Publications, Yearbooks and Other Printed Material Presented by Hunt Auctions Table of Contents 2-15 Signed Books: Sports 16-18 Signed Books: Celebrities & Notables 19-21 Signed Books: Political 22-34 High School & College Yearbooks: Sports 35-41 High School & College Yearbooks: Celebrities & Notables 42-44 High School & College Yearbooks: Political 45-56 Collegiate Yearbooks 57 High School Yearbooks 58-59 Publications: Celebrities/Notables/Sports 60 Other Printed Material Auction Closes August 12, 2009 | www.HuntAuctions.com 1 Auction of Publications, Yearbooks and Other Printed Material Presented by Hunt Auctions Signed Books: Sports 195 Hank Aaron signed "Aaron" hardcover book. (EX/MT) 306 Hank Aaron and Lonnie Wheeler signed "I Had A Hammer" hardcover book. (EX-EX/MT) 100 Kareem Abdul-Jabbar signed "Rookie the World of the NBA" hardcover book by David Klein. (EX) 106 Kareem Abdul-Jabbar signed "Stand Tall" hardcover book by Phil Pepe. (EX) 131 Tommie Agee, Cleon Jones, and Ron Swoboda multi-signed "A Magic Summer" hardcover book. (EX-EX/MT) 83 Muhammad Ali signed book His Life and Times (EX/MT) 90 Muhammad Ali signed Neil Leifer book Memories (EX/MT) 91 Muhammad Ali signed Neil Leifer book Memories (EX/MT) 94 Muhammad Ali twice signed book The Greatest (EX-EX/MT) 1443 Muhammad Ali signed book My Own Story (EX-EX/MT) 1444 Muhammad Ali signed book A View from the Corner (EX-EX/MT) 1445 Muhammad Ali signed book In This Corner (EX-EX/MT) 1446 Muhammad Ali signed book The Fighting Prophet (EX-EX/MT) 299 Mel Allen (d.1996) signed "The Men Of Autumn" hardcover book. -

Military Academy Established 1880 - Lexiivgtdiv, Mo

tmsssmu'^i'i lOENTUIDRTH MILITARY ACADEMY ESTABLISHED 1880 - LEXIIVGTDIV, MO. HIGH SCHOOL AND JUNIOR COLLEGE WENTWOHTH'S PURPOSE it is the purpose of Wentworth Military Academy to provide the best conditions possible for the all 'round development of worthy boys and young men. To attain this high purpose, the Academy places greatest emphasis upon these four points: First, it is the Academy's aim to assemble only the highest types of students—deserving youths of good parentage—to assure wholesome associations and greater progress. Every pre caution is taken to keep undesirable boys—all those that might prove detrimental to others— out of the Academy. Second, to employ only men of highest character and ability for its faculty. It is not enough for a Wentworth faculty member to be merely a scholar and a splendid instructor, hie must also possess a spirit of friendliness and a sincere desire to give kindly help whenever necessary. hHe must thoroughly understand the innermost problems of boys—be patient with them—and be ready to serve each boy to the best of his ability. Third, to provide the very best equipment throughout every department to the end that every boy will have all those things necessary to his health and happiness and that none shall want for anything that will help him to make progress. Fourth, to provide a program for each day that will best serve the interests of every student. WENTWDHTH FROM THE AIR No. I. Administration Building, "D" Company No. 9. Drill and Athletic Field. Barracks, Music Facilities and Rifle No.