The Rogiet Hoard and the Coinage of Allectus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Windmill Post May 2020 Online.Pub

Windmill Post May 2020 For the Communies of Rogiet and Llanfihangel In this issue: •Notice Board •Chairman’s update •Activites and resources for children •A message from Rogiet Community Junction •A message from Rogiet Covid -19 Community Support Group •List of grocery suppliers •VE Day celebrations 1 NOTICE BOARD Cyber Crime As some of you will already know Cyber Crime is on the up. You may have received messages claiming to be from HMRC or TV Licencing saying that you are owed money or your licence has run out. During this difficult time there are a variety of scams and more are coming to light daily. Do not click on any links or give any personal details. If you have any suspicions at all contact: Action Fraud Crime Line – 0300 1232040 Local Police on 101 or Police HQ 01633 838111 and ask to be put through to the Cyber Crime Unit. Church Notices Due to the current coronavirus pandemic the church buildings are closed for the foreseeable future. If you are on Facebook you can follow St Mary’s Church, who are posting the scripture references for each Sunday service, and other information and updates. Rogiet Countryside Park All parkruns worldwide are currently suspended. The countryside park remains open to locals and is a beautiful place to take your exercise, but please make sure you abide by social distancing rules. Please continue to clean up after your dog as usual; waste bins continue to be emptied during this time. 2 Rogiet Craft Group The group, led by Janet Fowler, have produced some lovely decorations to mark the 75th anniversary of VE day. -

Monmouthshire Local Development Plan (Ldp) Proposed Rural Housing

MONMOUTHSHIRE LOCAL DEVELOPMENT PLAN (LDP) PROPOSED RURAL HOUSING ALLOCATIONS CONSULTATION DRAFT JUNE 2010 CONTENTS A. Introduction. 1. Background 2. Preferred Strategy Rural Housing Policy 3. Village Development Boundaries 4. Approach to Village Categorisation and Site Identification B. Rural Secondary Settlements 1. Usk 2. Raglan 3. Penperlleni/Goetre C. Main Villages 1. Caerwent 2. Cross Ash 3. Devauden 4. Dingestow 5. Grosmont 6. Little Mill 7. Llanarth 8. Llandewi Rhydderch 9. Llandogo 10. Llanellen 11. Llangybi 12. Llanishen 13. Llanover 14. Llanvair Discoed 15. Llanvair Kilgeddin 16. Llanvapley 17. Mathern 18. Mitchell Troy 19. Penallt 20. Pwllmeyric 21. Shirenewton/Mynyddbach 22. St. Arvans 23. The Bryn 24. Tintern 25. Trellech 26. Werngifford/Pandy D. Minor Villages (UDP Policy H4). 1. Bettws Newydd 2. Broadstone/Catbrook 3. Brynygwenin 4. Coed-y-Paen 5. Crick 6. Cuckoo’s Row 7. Great Oak 8. Gwehelog 9. Llandegveth 10. Llandenny 11. Llangattock Llingoed 12. Llangwm 13. Llansoy 14. Llantillio Crossenny 15. Llantrisant 16. Llanvetherine 17. Maypole/St Maughans Green 18. Penpergwm 19. Pen-y-Clawdd 20. The Narth 21. Tredunnock A. INTRODUCTION. 1. BACKGROUND The Monmouthshire Local Development Plan (LDP) Preferred Strategy was issued for consultation for a six week period from 4 June 2009 to 17 July 2009. The results of this consultation were reported to Council in January 2010 and the Report of Consultation was issued for public comment for a further consultation period from 19 February 2010 to 19 March 2010. The present report on Proposed Rural Housing Allocations is intended to form the basis for a further informal consultation to assist the Council in moving forward from the LDP Preferred Strategy to the Deposit LDP. -

The Reign and Coinage of Carausius

58 REIGN AND COINAGE OF CARAUSIUS. TABLE OF MINT-MARKS. 1. MARKS ATTRIBUTABLE TO COLCHESTER.. Varietyor types noted. Marki. Suggested lnterretatlona.p Carauslna. Allectus. N JR IE N IE Cl· 6 3 The mark of Ce.mulodunum.1 • � I Ditto ·I· 2(?) 93 Ditto 3 Ditto, blundered. :1..:G :1..: 3 Ditto, retrograde. ·I· I Stukeley, Pl. uix. 2, probably OLA misread. ·I· 12 Camulodunum. One 21st part CXXI of a denarius. ·I· 26 Moneta Camulodunensis. MC ·I· I MC incomplete. 1 Moueta Camuloduuensis, &o. MCXXI_._,_. ·I· 5 1 Mone� . eignata Camulodu- MSC nene1s. __:.l_:__ 3 Moneta signata Ooloniae Ca- MSCC muloduneneie. I· 1 Moneta signata Ooloniae. MSCL ·I· I MCXXI blundered. MSXXI ·I· 1 1 Probably QC blundered. PC ·I· I(?; S8 Quinariue Camuloduneneis.11 cQ • 10 The city mark is sometimes found in the field on the coinage of Diocletian. 11 Cf. Num. Ohron., 1906, p. 132. MINT-MARKS. 59 MABKS ATTRIBUTABLE TO COLCHESTER-continued. Variety of types noted. Jl!arks. Suggested Interpretation•. Carauslus. Allectus. N IR IE. A/ IE. ·I· I Signata Camuloduni. SC ·I· 1 Signata. moneta Camulodu- SMC nensis. •I· I Signo.ta moneta Caruulodu- SMC nensis, with series mark. ·I· 7 4 Signata prima (offlcina) Ca- SPC mulodnnens�. ·I· 2 The 21st part of a donarius. XXIC Camulodunum. BIE I Secundae (offlcinac) emissa, CXXI &c. ·IC I Tortfo (offlcina) Camulodu- nensis. FIO I(?' Faciunda offlcina Camulodu- � nensis . IP 1 Prima offlcina Camulo,lu- � nensis. s I. 1 1 Incomplete. SIA 1 Signata prima (offlcina) Camu- lodunensis. SIA I Signata prima (officina) Co- CL loniae. -

Notice of Poll & Situation of Polling Stations Hysybsiad O Bleidleisio & Lleoliad Gorsafoedd Pleidleisio

NOTICE OF POLL & SITUATION OF POLLING STATIONS HYSYBSIAD O BLEIDLEISIO & LLEOLIAD GORSAFOEDD PLEIDLEISIO Local Authority Name: Monmouthshire County Council Enw’r awdurdod lleol: Cyngor Sir Fynwy Name of ward/area: Caerwent Enw’r ward/adran: Number of councillors to be elected in the ward/area: 1 Nefer y ceynghorwyr i’w hetol yn y ward adran hon: A poll will be held on 4 May 2017 between 7am and 10pm in this ward/area Cynhelir yr etholiad ar 4 Mai 2017 rhwng 7yb a 10yh yn y ward/adran hon The following people stand nominated for election to this ward/area Mae’r bobl a ganlyn wedi’u henwebu I sefyll i’w hethol Names of Signatories Name of Description (if Home Address Proposers(+), Seconders(++) & Candidate any) Assentors BURRETT 34 Severn Crescent, Welsh Labour Irene M.W. Hunt (+) Elizabeth M Gardiner (++) Lisset Maria Chepstow, NP16 5EA Candidate/Ymgeisydd Terry P Gardiner Andrew S Lauder Llafur Cymru David G Rogers Claire M Rogers Huw R Hudson Hilary A Counsell Brian W Counsell Ceri T Wynne KEEN 35 Ffordd Sain Ffwyst, Liberal Democrats Kerry J Wreford-Bush (+) Jodie Turner (++) Les Llanfoist, Abergavenny, Amy C Hanson Caroline L Morris NP7 9QF Timothy R Wreford-Bush Rebecca Bailey Gareth Davies Karen A Dally Martin D Dally Andrew J Twomlow MURPHY Swn Aderyn, Llanfair Welsh Conservative Suzanne J Murphy (+) William D James (++) Phil Discoed, Chepstow, Party Candidate Frances M James Christopher J Butler Monmouthshire, Kathleen N Butler Jacqueline G Williams NP16 6LX John A Williams Derek J Taylor Elsie I Taylor Karen L Wenborn NORRIE Fir Tree House, Crick UKIP Wales Clive J Burchill (+) Janice M Burchill (++) Gordon Road, Crick, Caldicot, Ivan J Weaver Kay Swift NP26 5UW Brian M Williams Amy Griffiths-Burdon Thomas A Evans Richard Martin Charles R Bedford Michael D Barnfather The situation of Polling Stations and the description of persons entitled to vote thereat are as follows: Mae lleoliadau’r Gorsafoedd Pleidleisio a disgrifiad o’r bobl sydd â hawl i bleidleisio yno fel y canlyn: No. -

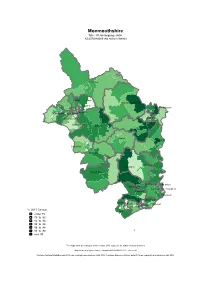

Monmouthshire Table: Welsh Language Skills KS207WA0009 (No Skills in Welsh)

Monmouthshire Table: Welsh language skills KS207WA0009 (No skills in Welsh) Crucorney Cantref Mardy Llantilio Crossenny Croesonen Lansdown Dixton with Osbaston Priory Llanelly Hill GrofieldCastle Wyesham Drybridge Llanwenarth Ultra Overmonnow Llanfoist Fawr Llanover Mitchel Troy Raglan Trellech United Goetre Fawr Llanbadoc Usk St. Arvans Devauden Llangybi Fawr St. Kingsmark St. Mary's Shirenewton Larkfield St. Christopher's Caerwent Thornwell Dewstow Caldicot Castle The Elms Rogiet West End Portskewett Green Lane %, 2011 Census Severn Mill under 79 79 to 82 82 to 84 84 to 86 86 to 88 88 to 90 over 90 The maps show percentages within Census 2011 output areas, within electoral divisions Map created by Hywel Jones. Variables KS208WA0022−27 corrected Contains National Statistics data © Crown copyright and database right 2013; Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2013 Monmouthshire Table: Welsh language skills KS207WA0010 (Can understand spoken Welsh only) Crucorney Mardy Llantilio Crossenny Cantref Lansdown Croesonen Priory Dixton with Osbaston Llanelly Hill Grofield Castle Drybridge Wyesham Llanwenarth Ultra Llanfoist Fawr Overmonnow Llanover Mitchel Troy Goetre Fawr Raglan Trellech United Llanbadoc Usk St. Arvans Devauden Llangybi Fawr St. Kingsmark St. Mary's Shirenewton Larkfield St. Christopher's Caerwent Thornwell Caldicot Castle Portskewett Rogiet Dewstow Green Lane The Elms %, 2011 Census West End Severn Mill under 1 1 to 2 2 to 2 2 to 3 3 to 4 4 to 5 over 5 The maps show percentages within Census 2011 -

Diocletian's New Empire

1 Diocletian's New Empire Eutropius, Brevarium, 9.18-27.2 (Eutr. 9.18-27.2) 18. After the death of Probus, CARUS was created emperor, a native of Narbo in Gaul, who immediately made his sons, Carinus and Numerianus, Caesars, and reigned, in conjunction with them, two years. News being brought, while he was engaged in a war with the Sarmatians, of an insurrection among the Persians, he set out for the east, and achieved some noble exploits against that people; he routed them in the field, and took Seleucia and Ctesiphon, their noblest cities, but, while he was encamped on the Tigris, he was killed by lightning. His son NUMERIANUS, too, whom he had taken with him to Persia, a young man of very great ability, while, from being affected with a disease in his eyes, he was carried in a litter, was cut off by a plot of which Aper, his father-in-law, was the promoter; and his death, though attempted craftily to be concealed until Aper could seize the throne, was made known by the odour of his dead body; for the soldiers, who attended him, being struck by the smell, and opening the curtains of his litter, discovered his death some days after it had taken place. 19. 1. In the meantime CARINUS, whom Carus, when he set out to the war with Parthia, had left, with the authority of Caesar, to command in Illyricum, Gaul, and Italy, disgraced himself by all manner of crimes; he put to death many innocent persons on false accusations, formed illicit connexions with the wives of noblemen, and wrought the ruin of several of his school-fellows, who happened to have offended him at school by some slight provocation. -

The M4 Motorway (Rogiet Toll Plaza, Monmouthshire) (50 Mph Speed Limit) Regulations 2010 (Revocation) Regulations 2019

Status: This is the original version (as it was originally made). This item of legislation is currently only available in its original format. WELSH STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 2019 No. 1306 (W. 227) ROAD TRAFFIC, WALES The M4 Motorway (Rogiet Toll Plaza, Monmouthshire) (50 mph Speed Limit) Regulations 2010 (Revocation) Regulations 2019 Made - - - - 3 October 2019 Laid before the National Assembly for Wales - - 7 October 2019 Coming into force - - 31 October 2019 The Welsh Ministers, in exercise of the powers conferred on them by section 17(2), (3) and (3ZAA) of the Road Traffic Regulation Act 1984(1), and after consultation with such representative organisations as were thought fit in accordance with section 134(10) of that Act, make the following Regulations. Title and commencement 1. The title of these Regulations is the M4 Motorway (Rogiet Toll Plaza, Monmouthshire) (50 mph Speed Limit) Regulations 2010 (Revocation) Regulations 2019 and they come into force on 31 October 2019. Revocation 2. The M4 Motorway (Rogiet Toll Plaza, Monmouthshire) (50 mph Speed Limit) Regulations 2010(2) are revoked. Ken Skates Minister for Economy and Transport, one of the 3 October 2019 Welsh Ministers (1) 1984 c. 27. Section 17(2) was amended by the New Roads and Street Works Act 1991 (c. 22), Schedule 8, paragraph 28(3) and the Road Traffic Act 1991 (c. 40), Schedule 4, paragraph 25 and Schedule 8. Section 17(3ZAA) was inserted by the Wales Act 2017 (c. 4), section 26(2). (2) S.I. 2010/1512 (W. 138). Document Generated: 2019-11-01 Status: This is the original version (as it was originally made). -

The Political and Military Aspects of Accession of Constantine the Great

Graeco-Latina Brunensia 24 / 2019 / 2 https://doi.org/10.5817/GLB2019-2-2 The Political and Military Aspects of Accession of Constantine the Great Stanislav Doležal (University of South Bohemia in České Budějovice) Abstract The article argues that Constantine the Great, until he was recognized by Galerius, the senior ČLÁNKY / ARTICLES Emperor of the Tetrarchy, was an usurper with no right to the imperial power, nothwithstand- ing his claim that his father, the Emperor Constantius I, conferred upon him the imperial title before he died. Tetrarchic principles, envisaged by Diocletian, were specifically put in place to supersede and override blood kinship. Constantine’s accession to power started as a military coup in which a military unit composed of barbarian soldiers seems to have played an impor- tant role. Keywords Constantine the Great; Roman emperor; usurpation; tetrarchy 19 Stanislav Doležal The Political and Military Aspects of Accession of Constantine the Great On 25 July 306 at York, the Roman Emperor Constantius I died peacefully in his bed. On the same day, a new Emperor was made – his eldest son Constantine who had been present at his father’s deathbed. What exactly happened on that day? Britain, a remote province (actually several provinces)1 on the edge of the Roman Empire, had a tendency to defect from the central government. It produced several usurpers in the past.2 Was Constantine one of them? What gave him the right to be an Emperor in the first place? It can be argued that the political system that was still valid in 306, today known as the Tetrarchy, made any such seizure of power illegal. -

A List of Churches and Ministry Areas in the Monmouth Archdeaconry

Monmouth Archdeaconry Ministry Areas No. 1 Abergavenny (St Mary, Christchurch) Llanwenarth (St Peter) Abergavenny (Holy Trinity) Govilon (Christchurch) Llanfoist (St Ffwyst) Llanelen (St Helen) No. 2 Llantilio Pertholey (St Teilo, Bettws Chapel) Llanfihangel Crucorney Group (United Parish of Crucorney) (St David, St Martin, St Michael) Grosmont (St Nicholas) Skenfrith (St Bride) Llanfair (St Mary) Llangattock Lingoed (St Cadoc) Llanaddewi Rydderch (St David) Llanarth & Llansantfraed (St Bridget) Llangattock - j - Usk (St Cadoc) Llantilio Crossenny (St Teilo) Penrhos (St Cadoc) Llanvetherine (St James the Elder) Llanvapley (St Mable) Llanddewi Skirrid (St David) No. 3 Dingestow (St Dingat) Cwmcarvan (St Catwg) Penyclawdd (St Martin) Tregaer (St Mary) Rockfield (St Cenhedlon) St Maughan's & Llangattock - Vibon Avel (St Meugan) Llanvihangel-ystern-llewern (St Michael) Monmouth (St Mary the Virgin) Overmonnow (St Thomas) Mitchel Troy (St Michael) Wonastow (St Wonnow) Llandogo (St Oudoceus) Llanishen (St Dennis) Trellech Grange (Parish Church) Llanfihangel-Tor-y-Mynydd (St Michael) Llansoy (St Tysoi) Trellech & Penallt (Old St Marys Church, St Nicholas) No. 4 Caerwent (St Stephen & St Tathan) Llanvair Discoed (St Mary) Penhow (St John the Baptist) St Brides Netherwent (St Bridget) Llanvaches (St Dubritius) Llandevaud (St Peter) Caldicot (St Mary the Virgin, St Marys Portskewett, St Marys Rogiet) Magor (Langstone Parish Church, St Cadwaladr, St Martin, St Mary Magdalene, St Marys Llanwern, St Marys Magor, St Marys Nash, St Marys Undy, St Marys -

Weekly List of Determined Planning Applications

Monmouthshire County Council Weekly List of Determined Planning Applications Week 02/08/2014 to 08/08/2014 Print Date 13/08/2014 Application No Development Description Decision SIte Address Decision Date Decision Level Community Council Caerwent DC/2014/00113 Outline application for dwelling at the rear of myrtle cottage Refuse Myrtle Cottage 06-August-2014 Committee The Cross Caerwent Caerwent Caldicot NP26 5AZ DC/2014/00712 Proposed alteration of approved dwelling to include rear conservatory extension. Approve C/O PLOT 51 05-August-2014 Delegated Castlemead Caerwent Ash Tree Road Caerwent NP26 5NU Caerwent 2 Crucorney DC/2014/00677 Replace existing roof lights and installation of new roof light Approve Old Garden 04-August-2014 Delegated Officer Grosmont Grosmont Abergavenny NP7 8EP DC/2014/00668 Replacement of velux roof light with new window Approve Steppes Barn 04-August-2014 Delegated Officer Grosmont Grosmont Abergavenny NP7 8HU Crucorney 2 Print Date 13/08/2014 MCC Weekly List of Registered Applications 02/08/2014 to 08/08/2014 Page 2 of 9 Application No Development Description Decision SIte Address Decision Date Decision Level Community Council Devauden DC/2014/00557 Erection of new garage & store Approve Court Robin House 04-August-2014 Delegated Court Robin Lane Llangwm Llangwm Monmouthshire NP26 1EF Devauden 1 Drybridge DC/2014/00826 Discharge of condition no. 3 of planning permission DC/2013/00205. Approve Trevor Bowen Court 06-August-2014 Delegated Officer Wonastow Road Monmouth Monmouth NP25 5BH Drybridge 1 Goytre Fawr DC/2014/00197 Erection of one dwelling and garage. Approve Land rear of 1 and 2 Bedfont Cottages 07-August-2014 Committee Newtown Road Goetre Fawr Goytre NP4 0AW Goytre Fawr 1 Green Lane DC/2014/00721 Single storey timber garden room to replace existing dilapidated concrete garage. -

The Cambridge Companion to Age of Constantine.Pdf

The Cambridge Companion to THE AGE OF CONSTANTINE S The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Constantine offers students a com- prehensive one-volume introduction to this pivotal emperor and his times. Richly illustrated and designed as a readable survey accessible to all audiences, it also achieves a level of scholarly sophistication and a freshness of interpretation that will be welcomed by the experts. The volume is divided into five sections that examine political history, reli- gion, social and economic history, art, and foreign relations during the reign of Constantine, a ruler who gains in importance because he steered the Roman Empire on a course parallel with his own personal develop- ment. Each chapter examines the intimate interplay between emperor and empire and between a powerful personality and his world. Collec- tively, the chapters show how both were mutually affected in ways that shaped the world of late antiquity and even affect our own world today. Noel Lenski is Associate Professor of Classics at the University of Colorado, Boulder. A specialist in the history of late antiquity, he is the author of numerous articles on military, political, cultural, and social history and the monograph Failure of Empire: Valens and the Roman State in the Fourth Century ad. Cambridge Collections Online © Cambridge University Press, 2007 Cambridge Collections Online © Cambridge University Press, 2007 The Cambridge Companion to THE AGE OF CONSTANTINE S Edited by Noel Lenski University of Colorado Cambridge Collections Online © Cambridge University Press, 2007 cambridge university press Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, Sao˜ Paulo Cambridge University Press 40 West 20th Street, New York, ny 10011-4211, usa www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521818384 c Cambridge University Press 2006 This publication is in copyright. -

A Tale of Two Periods

A tale of two periods Change and continuity in the Roman Empire between 249 and 324 Pictured left: a section of the Naqš-i Rustam, the victory monument of Shapur I of Persia, showing the captured Roman emperor Valerian kneeling before the victorious Sassanid monarch (source: www.bbc.co.uk). Pictured right: a group of statues found on St. Mark’s Basilica in Venice, depicting the members of the first tetrarchy – Diocletian, Maximian, Constantius and Galerius – holding each other and with their hands on their swords, ready to act if necessary (source: www.wikipedia.org). The former image depicts the biggest shame suffered by the empire during the third-century ‘crisis’, while the latter is the most prominent surviving symbol of tetrar- chic ideology. S. L. Vennik Kluut 14 1991 VB Velserbroek S0930156 RMA-thesis Ancient History Supervisor: Dr. F. G. Naerebout Faculty of Humanities University of Leiden Date: 30-05-2014 2 Table of contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................. 3 Sources ............................................................................................................................................ 6 Historiography ............................................................................................................................... 10 1. Narrative ............................................................................................................................................ 14 From