Assessment of the Attended Coupon-Operated Access-Point Cost Recovery System for Community Water Supply Schemes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kwazulu-Natal Provincial Gazette Vol 12 No 1964 Dated 14 June 2018

KWAZULU-NATAL PROVINCE KWAZULU-NATAL PROVINSIE ISIFUNDAZWE SAKwAZULU-NATALI Provincial Gazette • Provinsiale Koerant • Igazethi Yesifundazwe (Registered at the post office as a newspaper) • (As 'n nuusblad by die poskantoor geregistreer) (lrejistiwee njengephephandaba eposihhovisi) PIETERMARITZBURG Vol. 12 14 JUNE 2018 No. 1964 14 JUNIE 2018 14 KUNHLANGULANA 2018 2 No. 1964 PROVINCIAL GAZETTE, 14 JUNE 2018 IMPORTANT NOTICE: THE GOVERNMENT PRINTING WORKS WILL NOT BE HELD RESPONSIBLE FOR ANY ERRORS THAT MIGHT OCCUR DUE TO THE SUBMISSION OF INCOMPLETE I INCORRECT I ILLEGIBLE COPY. No FUTURE QUERIES WILL BE HANDLED IN CONNECTION WITH THE ABOVE. CONTENTS Gazette Page No. No. GENERAL NOTICES, ALGEMENE KENNISGEWINGS 23 KwaZulu-Natal Gaming and Betting Act, 2010 (Act No. 08 of 2010): Star Bingo KZN (Pty) Ltd ........................ 1964 11 23 KwaZulu-Natal Wet op Dobbelary en Weddery, 2010 (Wet No. 08 van 2010): Star Bingo KZN (Edms) Bpk.... 1964 12 PROVINCIAL NOTICES, PROVINSIALE KENNISGEWINGS 54 Local Government: Municipal Property Rates Act, 2004: Ubuhlebezwe Municipality: Property By-Laws 2018/2019........................................................................................................................................................... 1964 14 55 KwaZulu-Natal Land Administration and Immovable Asset Management Act (2/2014): Portion 246 of the Farm Zeekoegat No. 937, KwaZulu-Natal.......................................................................................................... 1964 30 56 Local Government: Municipal -

Government Gazette Staatskoerant REPUBLIC of SOUTH AFRICA REPUBLIEK VAN SUID-AFRIKA

Government Gazette Staatskoerant REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA REPUBLIEK VAN SUID-AFRIKA November Vol. 641 Pretoria, 9 2018 November No. 42025 PART 1 OF 2 LEGAL NOTICES A WETLIKE KENNISGEWINGS ISSN 1682-5843 N.B. The Government Printing Works will 42025 not be held responsible for the quality of “Hard Copies” or “Electronic Files” submitted for publication purposes 9 771682 584003 AIDS HELPLINE: 0800-0123-22 Prevention is the cure 2 No. 42025 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 9 NOVEMBER 2018 IMPORTANT NOTICE: THE GOVERNMENT PRINTING WORKS WILL NOT BE HELD RESPONSIBLE FOR ANY ERRORS THAT MIGHT OCCUR DUE TO THE SUBMISSION OF INCOMPLETE / INCORRECT / ILLEGIBLE COPY. NO FUTURE QUERIES WILL BE HANDLED IN CONNECTION WITH THE ABOVE. Table of Contents LEGAL NOTICES BUSINESS NOTICES • BESIGHEIDSKENNISGEWINGS Gauteng ....................................................................................................................................... 12 KwaZulu-Natal ................................................................................................................................ 13 Mpumalanga .................................................................................................................................. 13 North West / Noordwes ..................................................................................................................... 14 Northern Cape / Noord-Kaap ............................................................................................................. 14 Western Cape / Wes-Kaap ............................................................................................................... -

South Coast System

Infrastructure Master Plan 2020 2020/2021 – 2050/2051 Volume 4: South Coast System Infrastructure Development Division, Umgeni Water 310 Burger Street, Pietermaritzburg, 3201, Republic of South Africa P.O. Box 9, Pietermaritzburg, 3200, Republic of South Africa Tel: +27 (33) 341 1111 / Fax +27 (33) 341 1167 / Toll free: 0800 331 820 Think Water, Email: [email protected] / Web: www.umgeni.co.za think Umgeni Water. Improving Quality of Life and Enhancing Sustainable Economic Development. For further information, please contact: Planning Services Infrastructure Development Division Umgeni Water P.O.Box 9, Pietermaritzburg, 3200 KwaZulu‐Natal, South Africa Tel: 033 341‐1522 Fax: 033 341‐1218 Email: [email protected] Web: www.umgeni.co.za PREFACE This Infrastructure Master Plan 2020 describes: Umgeni Water’s infrastructure plans for the financial period 2020/2021 – 2050/2051, and Infrastructure master plans for other areas outside of Umgeni Water’s Operating Area but within KwaZulu-Natal. It is a comprehensive technical report that provides information on current infrastructure and on future infrastructure development plans. This report replaces the last comprehensive Infrastructure Master Plan that was compiled in 2019 and which only pertained to the Umgeni Water Operational area. The report is divided into ten volumes as per the organogram below. Volume 1 includes the following sections and a description of each is provided below: Section 2 describes the most recent changes and trends within the primary environmental dictates that influence development plans within the province. Section 3 relates only to the Umgeni Water Operational Areas and provides a review of historic water sales against past projections, as well as Umgeni Water’s most recent water demand projections, compiled at the end of 2019. -

Heritage Impact Assessment of Kwangqathu Residential Development, Ntshongweni, Kwazulu-Natal, South Africa

HERITAGE IMPACT ASSESSMENT OF KWANGQATHU RESIDENTIAL DEVELOPMENT, NTSHONGWENI, KWAZULU-NATAL, SOUTH AFRICA Assessment and report by For Balanced Environment Telephone Sue George 082 961 5750 Box 20057 Ashburton 3213 PIETERMARITZBURG South Africa Telephone 033 326 1136 Facsimile 086 672 8557 082 655 9077 / 072 725 1763 [email protected] 30 November 2007 HERITAGE IMPACT ASSESSMENT OF KWANGQATHU RESIDENTIAL DEVELOPMENT, NTSHONGWENI, KWAZULU-NATAL Management summary eThembeni Cultural Heritage was appointed by Balanced Environment to undertake a heritage impact assessment of a proposed residential development in Ntshongweni, in terms of the KwaZulu-Natal Heritage Act No 10 of 1997. Two eThembeni staff members inspected the area on 22 November 2007 and completed a controlled-exclusive surface survey, as well as a database and literature search. At least two places with heritage significance are located within the proposed development area. A Shembe Church site is demarcated with white stones, while the precinct of the Ntshangwe Catholic Church, established in 1938, includes buildings that are older than sixty years. Neither place, nor any structures older than sixty years, may be altered in any way without a permit from Amafa aKwaZulu- Natali. Both places of worship identified above are associated with living heritage, while the Catholic Church precinct could be considered as a historical settlement. The same restrictions in terms of alteration apply. The proposed development area comprises semi-rural scattered settlement with mostly informal dwellings interspersed by tuck shops, an informal taxi rank, the existing church precinct and school site, an abandoned satellite police station and open grassland, some of which is disturbed by historic farming, building or borrow pit activities. -

Provide Bulk Water and Sanitation Services to Improve Quality of Life

Provide bulk water and sanitation services to improve quality of life and enhance sustainable economic development IMVUTSHANE DAM 1 8.0 PG 57-63 9.0 PG 65-81 10.0 PG 83-93 11.0 PG 95-103 12.0 PG 105-111 13.0 PG 113-197 14.0 PG 199-204 UMGENI WATER • AMANZI PERFORMANCE AGAINST CREATING CONSERVING ENABLING IMPROVING FINANCIAL GRI CONTENT ANNUAL REPORT 2016/2017 SHAREHOLDER VALUE OUR NATURAL OUR PEOPLE RESILIENCY SUSTAINABILITY INDEX 2016/2017 COMPACT RESOURCES “Umgeni Water in numbers – An efficient, innovative and responsible organisation on the move” 410 million 33 million cubic metres of potable water per annum cubic metres (90 Ml/d) of (1 123 Ml/d) provided wastewater to 6 customers treated in 2016/2017 R1 163 million 72% of target water total CAPEX Spend (Parent), of which R503 million went towards infrastructure project projects for rural development milestones were met Financial Viability Umgeni Water maintained positive results in the 1 150 year due to continued sound fi nancial management: Revenue (Group) Surplus for the year Balance sheet Umgeni generated was (Group) was reserves were R2.5 R746 R6.8 Water billion MILLION billion Group employees In 2017 In 2017 In 2017 2 1.0 PG 7 2.0 PG 9-17 3.0 PG 18-21 4.0 PG 22-25 5.0 PG 26-33 6.0 PG 35-48 7.0 PG 51-54 UMGENI WATER • AMANZI ANNUAL REPORT REPORT ORGANISATIONAL MINISTER’S ACCOUNTING CHIEF EXECUTIVE’S CORPORATE STAKEHOLDER 2016/2017 PROFILE PROFILE FOREWORD AUTHORITY’S REPORT GOVERNANCE UNDERSTANDING REPORT AND SUPPORT Vision Leading water utility that enhances value in the provision of bulk water and sanitation services. -

Kwazulu-Natal

KwaZulu-Natal Municipality Ward Voting District Voting Station Name Latitude Longitude Address KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305001 11830014 INDAWANA PRIMARY SCHOOL -29.99047 29.45013 NEXT NDAWANA SENIOR SECONDARY ELUSUTHU VILLAGE, NDAWANA A/A UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305001 11830025 MANGENI JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL -30.06311 29.53322 MANGENI VILLAGE UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305001 11830081 DELAMZI JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL -30.09754 29.58091 DELAMUZI UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305001 11830799 LUKHASINI PRIMARY SCHOOL -30.07072 29.60652 ELUKHASINI LUKHASINI A/A UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305001 11830878 TSAWULE JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL -30.05437 29.47796 TSAWULE TSAWULE UMZIMKHULU RURAL KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305001 11830889 ST PATRIC JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL -30.07164 29.56811 KHAYEKA KHAYEKA UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305001 11830890 MGANU JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL -29.98561 29.47094 NGWAGWANE VILLAGE NGWAGWANE UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305001 11831497 NDAWANA PRIMARY SCHOOL -29.98091 29.435 NEXT TO WESSEL CHURCH MPOPHOMENI LOCATION ,NDAWANA A/A UMZIMKHULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305002 11830058 CORINTH JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL -30.09861 29.72274 CORINTH LOC UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305002 11830069 ENGWAQA JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL -30.13608 29.65713 ENGWAQA LOC ENGWAQA UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305002 11830867 NYANISWENI JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL -30.11541 29.67829 ENYANISWENI VILLAGE NYANISWENI UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305002 11830913 EDGERTON PRIMARY SCHOOL -30.10827 29.6547 EDGERTON EDGETON UMZIMKHULU -

2017/18 – 2021/22 Idp

. 2017/18 – 2021/22 IDP CONTENTS 1 CHAPTER 1: EXECUTIVE SUMMARY……………………… ................................................................... 4 1.1 LOCATION: WHO ARE WE? .............................................................................................................. 4 2. CHAPTER 2: PLANNING AND DEVELOPMENT PRINCIPLES ........................................................... 7 2.1 LEGISLATIVE FRAMEWORK ........................................................................................................ 7 2.1 POLICY FRAMEWORK ................................................................................................................ 9 3. CHAPTER 3 SITUATIONAL ANALYSIS ........................................................................................ 17 3.1 DEMOGRAPHICS ..................................................................................................................... 17 3.1.1 Population .............................................................................................................................. 17 3.1.2 Gender Composition ............................................................................................................... 18 3.1.3 Age Group .............................................................................................................................. 18 3.1.4 Population Group ................................................................................................................... 19 3.1.5 Employment Status................................................................................................................ -

Heritage Impact Assessment of Port Edward / Harding Power Lines, Kwazulu-Natal and Eastern Cape Provinces, South Africa

HERITAGE IMPACT ASSESSMENT OF PORT EDWARD / HARDING POWER LINES, KWAZULU-NATAL AND EASTERN CAPE PROVINCES, SOUTH AFRICA Assessment and report by For SiVEST Telephone Richard Kinvig 033 345 2702; Fax 033 345 2672 Box 20057 Ashburton 3213 PIETERMARITZBURG South Africa Telephone 033 326 1136 Facsimile 086 672 8557 082 655 9077 / 072 725 1763 [email protected] 21 August 2008 HERITAGE IMPACT ASSESSMENT OF PORT EDWARD / HARDING POWER LINES, KWAZULU-NATAL AND EASTERN CAPE Management summary eThembeni Cultural Heritage was appointed by SiVEST to undertake a heritage impact assessment of three proposed power line routes between Port Edward and Harding. Since the proposed servitudes are located in both KwaZulu-Natal and the Eastern Cape, both the KwaZulu-Natal Heritage Act No 10 of 1997 and the Heritage Resources Management Act No 25 of 1999 apply to this project. Two eThembeni staff members inspected the area on 30 and 31 July and 1 August 2008 and completed a controlled-exclusive surface survey, as well as a database and literature search. The purpose of this heritage impact assessment has been to identify two preferred power line servitudes between Port Edward and Harding. Of the three route alternatives that we examined, none is preferable; i.e. all three are equally (un)likely to affect heritage resources. We recommend that a heritage practitioner return to the study area to survey both final servitudes, including an examination of exact tower placements and all construction infrastructure (contractor’s camp, access roads, etc.) before the start of any construction activities, to ensure that no heritage resources are affected. -

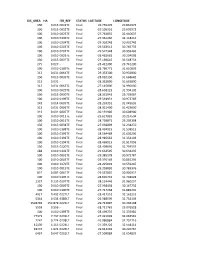

Gis Area Ha Itb Ref Status Latitude

GIS_AREA HA ITB_REF STATUS LATITUDE LONGITUDE 150 0.015 0031TE Final -29.755376 29.861975 150 0.015 0032TE Final -29.105316 29.699972 100 0.010 0025TE Final -27.764855 32.440637 100 0.010 0196TE Final -27.961260 32.118216 100 0.010 0204TE Final -29.303248 30.901742 100 0.010 0203TE Final -29.563513 30.765735 100 0.010 0201TE Final -29.572348 30.959465 100 0.010 0026TE Final -28.482681 30.204008 150 0.015 0037TE Final -27.169616 32.548754 275 0.027 - Final -28.412300 29.741200 100 0.010 0189TE Final -28.786771 31.610895 313 0.031 0064TE Final -29.353300 30.932800 150 0.015 0035TE Final -28.010150 31.668642 313 0.031 - Final -28.352800 31.655800 313 0.031 0063TE Final -27.145800 31.990000 100 0.010 0029TE Final -28.658123 31.994102 150 0.015 0030TE Final -28.331943 29.703087 100 0.010 0199TE Final -29.518951 30.973769 143 0.014 0005TE Final -28.293351 32.045095 313 0.031 0006TE Final -28.321400 31.423600 313 0.031 0007TE Final -30.191900 30.608900 100 0.010 0011TE Final -29.627881 30.214504 100 0.010 0016TE Final -28.759872 29.209398 150 0.015 0038TE Final -27.038009 32.238250 100 0.010 0188TE Final -28.494915 31.538515 100 0.010 0191TE Final -28.564468 31.636206 100 0.010 0192TE Final -28.985662 31.354103 100 0.010 0194TE Final -28.469913 31.917096 150 0.015 0220TE Final -28.403692 31.704555 188 0.019 0141TE Final -29.632595 30.634235 100 0.010 0001TE Final -29.385178 30.972787 100 0.010 0003TE Final -29.376149 30.865294 100 0.010 1470TE Final -28.225001 30.559247 100 0.010 0015TE Final -29.259892 30.783376 822 0.082 0062TE Final -29.537835 -

Assessmemt of the Attended Coupon* Access-Point Cost Recovery Systemfor Tjr N/ Community Water Supply Schemes

Assessmemt of the Attended Coupon* Access-Point Cost Recovery Systemfor tjr n/ Community Water Supply Schemes Lima Rural Development Foundation -.3C International Wats' •E.nd Sanitation Centre Tr1 ' *31 7O 30 689 80 -"•n K4 TT150/01 Wateir Research Commission ASSESSMENT OF THE ATTENDED COUPON-OPERATED ACCESS-POINT COST RECOVERY SYSTEM FOR COMMUNITY WATER SUPPLY SCHEMES Repor Watee th o trt Research Commission By LIMA RURAL DEVELOPMENT FOUNDATION WRC Report No: TT150/01 March 2001 Obtainable from: Water Research Commission PO Box 824 Pretoria 0001 The publication of this report emanates from a project entitled: A Case Study to Assess the Attended Coupon-Operated Access-Point Cost Recovery system for Community Water Supply Schemes(WRC Project No K5/1052) DISCLAIMER This report has been reviewed by the Water Research Commission (WRC) and approve publicationr dfo . Approval doe signift sno y thacontente th t s necessarily reflec viewe policietth d WRCe san th doer f so no , s mentio f tradno e namer so commercial products constitute endorsemen recommendatior to user nfo . ISBN 1868457168 Printe Republie th dn i Soutf co h Africa EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Poor cost recovery has been identified as the most limiting constraint to the sustainability of rural water supply schemes in Africa. Research has shown that inadequate cost recovery result: sin • Wealth influentiad yan l community members subsidreceivina f o y ygwa more th en i than poorer members, • Communities believe that water provision is cheap, • Limited government fund requiree sar operatdo t maintaid ean n existing schemes, rather than investing in new schemes. • As there are not economically viable schemes fail. -

9/10 November 2013 Voting Station List Kwazulu-Natal

9/10 November 2013 voting station list KwaZulu-Natal Municipality Ward Voting Voting station name Latitude Longitude Address district ETH - eThekwini [Durban 59500001 43400179 NOMFIHLELA PRIMARY -29.66898 30.62643 9 VIA UMSUNDUZI CLINIC, KWA XIMBA, ETHEKWINI Metro] SCHOOL ETH - eThekwini [Durban 59500001 43400180 OTHWEBA PRIMARY SCHOOL -29.69508 30.59244 , OTHEBA, KWAXIMBA Metro] ETH - eThekwini [Durban 59500001 43400191 CATO RIDGE LIBRARY -29.73666 30.57885 OLD MAIN ROAD, CATO RIDGE, ETHEKWINI Metro] ACTIVITIES ROOM ETH - eThekwini [Durban 59500001 43400528 NGIDI PRIMARY SCHOOL -29.653894 30.660039 BHOBHONONO, KWA XIMBA, ETHEKWINI Metro] ETH - eThekwini [Durban 59500001 43400539 MVINI PRIMARY SCHOOL -29.63687 30.671642 MUTHI ROAD, CATO RIDGE, KWAXIMBA Metro] ETH - eThekwini [Durban 59500001 43400595 XIMBA COMMUNITY HALL -29.66559 30.636613 KWAXIMBA MAIN ROAD, NO. 9 AREA, XIMBA TRIBAL Metro] AUTHORITY,CATO RIDGE, ETHEKWINI ETH - eThekwini [Durban 59500001 43400607 MABHILA PRIMARY SCHOOL -29.683425 30.63102 NAGLE ISAM RD, CATO RIDGE, ETHEKWINI Metro] ETH - eThekwini [Durban 59500001 43400618 NTUKUSO PRIMARY SCHOOL -29.67385 30.58848 NUBE ROAD, KWAXIMBA, ETHEKWINI Metro] ETH - eThekwini [Durban 59500001 43400696 INGCINDEZI PRIMARY SCHOOL -29.705158 30.577373 ALICE GOSEWELL ROUD, CATO RIDGE, ETHEKWINI Metro] ETH - eThekwini [Durban 59500001 43400708 INSIMANGWE PRIMARY -29.68598 30.61588 MAQATHA ROAD, CATO RIDGE, KWAXIMBA TC Metro] SCHOOL ETH - eThekwini [Durban 59500001 43400719 INDUNAKAZI PRIMARY -29.67793 30.70337 D1004 PHUMEKHAYA ROAD, -

1117 20-3 Kzng13

KWAZULU-NATAL PROVINCE RKEPUBLICWAZULU-NATAL PROVINSIEREPUBLIIEK OF VAN SOUTHISIFUNDAZWEAFRICA SAKWAZULUSUID-NATALI-AFRIKA Provincial Gazette • Provinsiale Koerant • Igazethi Yesifundazwe GAZETTE EXTRAORDINARY—BUITENGEWONE KOERANT—IGAZETHI EYISIPESHELI (Registered at the post office as a newspaper) • (As ’n nuusblad by die poskantoor geregistreer) (Irejistiwee njengephephandaba eposihhovisi) PIETERMARITZBURG, 20 MARCH 2014 Vol. 8 20 MAART 2014 No. 1117 20 kuNDASA 2014 We oil hawm he power to preftvent kllDc AIDS HEIRINE 0800 012 322 DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH Prevention is the cure N.B. The Government Printing Works will not be held responsible for the quality of “Hard Copies” or “Electronic Files” submitted for publication purposes 401207—A 1117—1 2 Extraordinary Provincial Gazette of KwaZulu-Natal 20 March 2014 IMPORTANT NOTICE The Government Printing Works will not be held responsible for faxed documents not received due to errors on the fax machine or faxes received which are unclear or incomplete. Please be advised that an “OK” slip, received from a fax machine, will not be accepted as proof that documents were received by the GPW for printing. If documents are faxed to the GPW it will be the sender’s respon- sibility to phone and confirm that the documents were received in good order. Furthermore the Government Printing Works will also not be held responsible for cancellations and amendments which have not been done on original documents received from clients. Page No. ADVERTISEMENT Road Carrier Permits, Pietermaritzburg........................................................................................................................