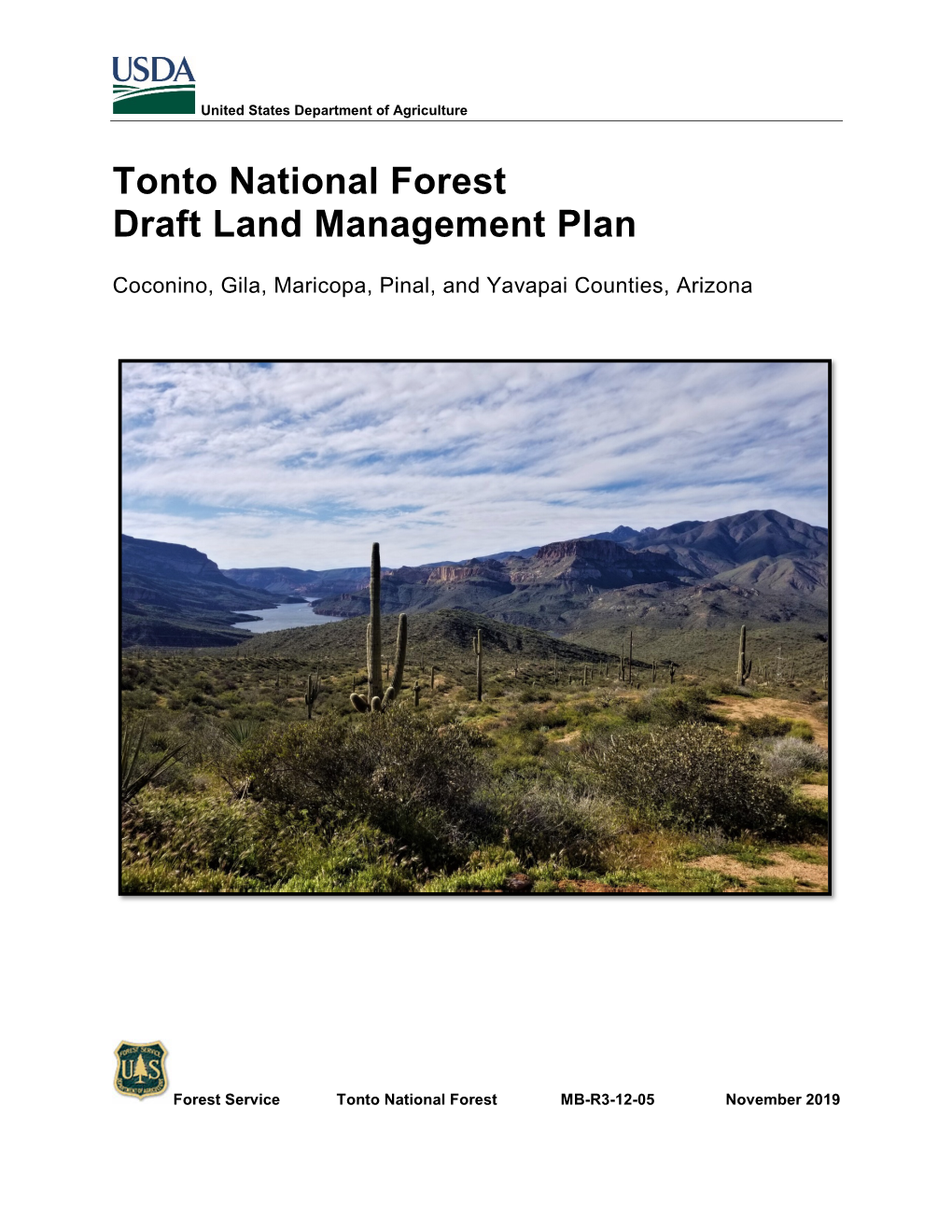

Tonto National Forest Draft Land Management Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tonto National Forest Travel Management Plan

Comments on the DEIS for the Tonto National Forest Travel Management Plan Submitted September 15, 2014 via Electronic Mail and Certified Mail #7014-0150-0001-2587-0812 On Behalf of: Archaeology Southwest Center for Biological Diversity Sierra Club The Wilderness Society WildEarth Guardians Table of Contents II. Federal Regulation of Travel Management .................................................................................. 4 III. Impacts from Year Round Motorized Use Must be Analyzed .................................................. 5 IV. The Forest Service’s Preferred Alternative .............................................................................. 6 V. Desired Conditions for Travel Management ................................................................................. 6 VI. Purpose and Need Statements ................................................................................................... 7 VII. Baseline Determination .............................................................................................................. 8 A. The Forest Service cannot arbitrarily reclassify roads as “open to motor vehicle use” in the baseline. ............................................................................................................................................ 10 B. Classification of all closed or decommissioned routes as “open to motor vehicle use” leads to mischaracterization of the impacts of the considered alternatives. ...................................................... 11 C. Failure -

Initial Assessment of Water Resources in Cobre Valley, Arizona

Initial Assessment of Water Resources in Cobre Valley, Arizona Introduction 2 Overview of Cobre Valley 3 CLIMATE 3 TOPOGRAPHY 3 GROUNDWATER 3 SURFACE WATER 4 POPULATION 5 ECONOMY 7 POLLUTION AND CONTAMINATION 8 Status of Municipal Water Resources 10 GLOBE, AZ 10 MIAMI, AZ 12 TRI-CITIES (CLAYPOOL, CENTRAL HEIGHTS, MIDLAND CITY) AND UNINCORPORATED AREAS 15 Water Resources Uncertainty and Potential 18 INFRASTRUCTURE FUNDING 18 SUSTAINABLE WELLFIELDS AND ALTERNATIVE WATER SUPPLIES 19 PRIVATE WELL WATER SUPPLY AND WATER QUALITY 20 PUBLIC EDUCATION 20 ENVIRONMENTAL ISSUES 21 References 23 Appendices 25 1. ARIZONA WATER COMPANY VS CITY OF GLOBE LAWSUIT 25 2. AGENT ORANGE APPLICATION IN THE 1960s 26 3. INFRASTRUCTURE UPGRADES IN THE CITY OF GLOBE 27 Initial Assessment of Water Resources in Cobre Valley, Arizona 1 Introduction This initial assessment of water resources in the Cobre Valley provides a snapshot of available data and resources on various water-related topics from all known sources. This report is the first step in determining where data are lacking and what further investigation may be necessary for community planning and resource development purposes. The research has been driven by two primary questions: 1) What information and resources currently exist on water resources in Cobre Valley and 2) what further research is necessary to provide valuable and accurate information so that community members and decision makers can reach their long-term water resource management goals? Areas of investigation include: water supply, water quality, drought and floods, economic factors, and water-dependent environmental values. Research for this report was conducted through the systematic collection of data and information from numerous local, state, and federal sources. -

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 04/01/2021 to 06/30/2021 Coronado National Forest This Report Contains the Best Available Information at the Time of Publication

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 04/01/2021 to 06/30/2021 Coronado National Forest This report contains the best available information at the time of publication. Questions may be directed to the Project Contact. Expected Project Name Project Purpose Planning Status Decision Implementation Project Contact Projects Occurring Nationwide Gypsy Moth Management in the - Vegetation management Completed Actual: 11/28/2012 01/2013 Susan Ellsworth United States: A Cooperative (other than forest products) 775-355-5313 Approach [email protected]. EIS us *UPDATED* Description: The USDA Forest Service and Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service are analyzing a range of strategies for controlling gypsy moth damage to forests and trees in the United States. Web Link: http://www.na.fs.fed.us/wv/eis/ Location: UNIT - All Districts-level Units. STATE - All States. COUNTY - All Counties. LEGAL - Not Applicable. Nationwide. Locatable Mining Rule - 36 CFR - Regulations, Directives, In Progress: Expected:12/2021 12/2021 Sarah Shoemaker 228, subpart A. Orders NOI in Federal Register 907-586-7886 EIS 09/13/2018 [email protected] d.us *UPDATED* Est. DEIS NOA in Federal Register 03/2021 Description: The U.S. Department of Agriculture proposes revisions to its regulations at 36 CFR 228, Subpart A governing locatable minerals operations on National Forest System lands.A draft EIS & proposed rule should be available for review/comment in late 2020 Web Link: http://www.fs.usda.gov/project/?project=57214 Location: UNIT - All Districts-level Units. STATE - All States. COUNTY - All Counties. LEGAL - Not Applicable. These regulations apply to all NFS lands open to mineral entry under the US mining laws. -

Pinal Creek Trail

Pinal Creek Trail Conceptual Plan November 2012 COBRE VALLEY COMPREHENSIVE TRANSPORTATION STUDY PINAL CREEK TRAIL CONCEPTUAL PLAN Final Report November 2012 Prepared For: City of Globe and Gila County Funded By: ADOT Planning Assistance for Rural Areas (PARA) Program Prepared By: Trail graphic prepared by RBF Consulting Cobre Valley Comprehensive Transportation Study TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 1. INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Purpose of the Study ............................................................................................................................ 1 1.2 Study Objectives ................................................................................................................................... 1 1.3 Study Area Overview ........................................................................................................................... 2 1.4 Study Process......................................................................................................................................... 3 2. REVIEW OF 1992 PINAL CREEK LINEAR PARK CONCEPT ............................................................... 4 2.1 1992 Pinal Creek Linear Park Concept Report ............................................................................... 4 2.2 1992 Pinal Creek Linear Park Goals ................................................................................................. 4 2.3 Original Pinal -

Ecotourism Outlook 2019 Prepared for the 2019 Outlook Marketing Forum

Ecotourism Outlook 2019 Prepared for the 2019 Outlook Marketing Forum Prepared by: Qwynne Lackey, Leah Joyner & Dr. Kelly Bricker, Professor University of Utah Ecotourism and Green Economy What is Ecotourism? Ecotourism is a subsector of the sustainable tourism industry that emphasizes social, environmental, and economic sustainability. When implemented properly, ecotourism exemplifies the benefits of responsible tourism development and management. TIES announced that it had updated its definition of ecotourism in 2015. This revised definition is more inclusive, highlights interpretation as a pillar of ecotourism, and is less ambiguous than the version adopted 25 years prior. In 2018, no new alterations were made to this highly cited definition which describes ecotourism as: “Responsible travel to natural areas that conserves the environment, sustains the well-being of the local people and involves interpretation and education.”1 This definition clearly outlines the key components of ecotourism: conservation, communities, and sustainable travel. Ecotourism represents a set of principles that have been successfully implemented in various communities and supported by extensive industry practice and academic research. Twenty-eight years since TIES was started, it is important to re-visit three principles found in TIES literature – that ecotourism: • is NON-CONSUMPTIVE / NON-EXTRACTIVE • creates an ecological CONSCIENCE • holds ECO-CENTRIC values and ethics in relation to nature TIES considers non-consumptive and non-extractive use of resources for and by tourists and minimized impacts to the environment and people as major characteristics of authentic ecotourism. What are the Principles of Ecotourism? Since 1990, when TIES framework for ecotourism principles was established, we have learned more about the tourism industry through scientific and design-related research and are also better informed about environmental degradation and impacts on local cultures and non-human species. -

AP Press Release

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: GOLETA, California: February 28, 2017 Breathtaking Adventures Offered this Spring Break What better way to utilize a week of freedom than to explore the great outdoors and see what all those rambling nature poets you read about in your American Literature class were talking about? UCSB Adventure Programs brings you a wide array of adventures to choose from for this spring break. This year’s trips include: AdventureFest, Grand Canyon Backpacking, The Lost Coast Backpacking Trip, The Colorado River Canoe, and The Santa Cruz Island Stewardship Adventure. Take the grand tour of the glorious southwest with AdventureFest. From March 25th to April 2nd, this nine day trip features the exploration of Joshua Tree National Park, the Colorado River through Black Canyon, and Zion National Park. This trip will test the limits of your mind and body with a variety of excursions, including canoeing, hiking, camping, and rock climbing! You must have a belay test and be able to swim for the trip. While no hiking experience is necessary, you must be in good physical condition to handle the nonstop adventure of this trip, so make sure you have been hitting the gym! Camping and hiking inside the sky-high walls of the Grand Canyon is something that few people get to experience in their life. The Grand Canyon backpacking trip takes place over the course of a week from March 26th to April 2nd. You will meet early on the first day at UCSB to drive to the canyon. On the second day you hike for over 9 miles into the canyon and spend the next five days hiking, camping, and exploring in the canyon. -

John D Walker and The

JOHN HENRY PEARCE by Tom Kollenborn © 1984 John Henry Pearce was truly an interesting pioneer of the Superstition Mountain and Goldfield area. His charismatic character endeared him to those who called him friend. Pearce was born in Taylor, Arizona, on January 22, 1883. His father founded and operated Pearce’s Ferry across the Colorado River near the western end of the Grand Canyon. Pearce’s father had accompanied John Wesley Powell through the Grand Canyon in 1869. John Pearce began his search for Jacob Waltz’s gold in 1929, shortly after arriving in the area. When John first arrived, he built a cabin on the Apache Trail about seven miles north- east of Apache Junction. Before moving to his Apache Trail site, John mined three gold mines and hauled his ore to the Hayden mill on the Gila River. He sold his gold to the United States government for $35.00 an ounce. During the depression his claims around the Goldfield area kept food on the table for his family. All the years John Pearce lived on the Apache Trail he also maintained a permanent camp deep in the Superstition Wilderness near Weaver’s Needle in Needle Canyon. He operated this camp from 1929 to the time of his death in 1959. John traveled the eleven miles to his camp by driving his truck to County Line Divide, then he would hike or ride horseback to his Needle Canyon Camp. Actually, Pearce had two mines in the Superstition Wilderness— one near his Needle Canyon Camp and the other located near Black Mesa Ridge. -

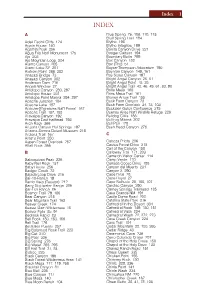

Index 1 INDEX

Index 1 INDEX A Blue Spring 76, 106, 110, 115 Bluff Spring Trail 184 Adeii Eechii Cliffs 124 Blythe 198 Agate House 140 Blythe Intaglios 199 Agathla Peak 256 Bonita Canyon Drive 221 Agua Fria Nat'l Monument 175 Booger Canyon 194 Ajo 203 Boundary Butte 299 Ajo Mountain Loop 204 Box Canyon 132 Alamo Canyon 205 Box (The) 51 Alamo Lake SP 201 Boyce-Thompson Arboretum 190 Alstrom Point 266, 302 Boynton Canyon 149, 161 Anasazi Bridge 73 Boy Scout Canyon 197 Anasazi Canyon 302 Bright Angel Canyon 25, 51 Anderson Dam 216 Bright Angel Point 15, 25 Angels Window 27 Bright Angel Trail 42, 46, 49, 61, 80, 90 Antelope Canyon 280, 297 Brins Mesa 160 Antelope House 231 Brins Mesa Trail 161 Antelope Point Marina 294, 297 Broken Arrow Trail 155 Apache Junction 184 Buck Farm Canyon 73 Apache Lake 187 Buck Farm Overlook 34, 73, 103 Apache-Sitgreaves Nat'l Forest 167 Buckskin Gulch Confluence 275 Apache Trail 187, 188 Buenos Aires Nat'l Wildlife Refuge 226 Aravaipa Canyon 192 Bulldog Cliffs 186 Aravaipa East trailhead 193 Bullfrog Marina 302 Arch Rock 366 Bull Pen 170 Arizona Canyon Hot Springs 197 Bush Head Canyon 278 Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum 216 Arizona Trail 167 C Artist's Point 250 Aspen Forest Overlook 257 Cabeza Prieta 206 Atlatl Rock 366 Cactus Forest Drive 218 Call of the Canyon 158 B Calloway Trail 171, 203 Cameron Visitor Center 114 Baboquivari Peak 226 Camp Verde 170 Baby Bell Rock 157 Canada Goose Drive 198 Baby Rocks 256 Canyon del Muerto 231 Badger Creek 72 Canyon X 290 Bajada Loop Drive 216 Cape Final 28 Bar-10-Ranch 19 Cape Royal 27 Barrio -

Shirak Guidebook

Wuthering Heights of Shirak -the Land of Steppe and Sky YYerevanerevan 22013013 1 Facts About Shirak FOREWORD Mix up the vast open spaces of the Shirak steppe, the wuthering wind that sweeps through its heights, the snowcapped tops of Mt. Aragats and the dramatic gorges and sparkling lakes of Akhurian River. Sprinkle in the white sheep fl ocks and the cry of an eagle. Add churches, mysterious Urartian ruins, abundant wildlife and unique architecture. Th en top it all off with a turbulent history, Gyumri’s joi de vivre and Gurdjieff ’s mystical teaching, revealing a truly magnifi cent region fi lled with experi- ences to last you a lifetime. However, don’t be deceived that merely seeing all these highlights will give you a complete picture of what Shirak really is. Dig deeper and you’ll be surprised to fi nd that your fondest memories will most likely lie with the locals themselves. You’ll eas- ily be touched by these proud, witt y, and legendarily hospitable people, even if you cannot speak their language. Only when you meet its remarkable people will you understand this land and its powerful energy which emanates from their sculptures, paintings, music and poetry. Visiting the province takes creativity and imagination, as the tourist industry is at best ‘nascent’. A great deal of the current tourist fl ow consists of Diasporan Armenians seeking the opportunity to make personal contributions to their historic homeland, along with a few scatt ered independent travelers. Although there are some rural “rest- places” and picnic areas, they cater mainly to locals who want to unwind with hearty feasts and family chats, thus rarely providing any activities. -

Table of Contents

TABLEGUIDELINES OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 12: CONTACT INFORMATION AND MAPS 12.1 ADOT CONTACT INFORMATION……………………………………………….......122 12.2 BLM CONTACT INFORMATION…………………………………………………......123 12.3 USFS CONTACT INFORMATION………………………………………………….....124 12.4 FHWA CONTACT INFORMATION…………………………………………………....130 12.5 GIS INFORMATION..............................................................................................131 12.6 MAPS...................................................................................................................132 121 12.1 ADOT CONTACT INFORMATION ADOT web link azdot.gov/ ADOT maps azdot.gov/maps General Information 602-712-7355 OFFICE ADOT DIRECTOR 602.712.7227 Deputy Director of Transportation 602.712.7391 Deputy Director of Policy 602.712.7550 Deputy Director of Business Operations 602.712.7228 Multimodal Planning Division (MPD) Director 602.712.7431 MPD Planning and Programming Director 602.712.8140 MPD Planning and Environmental Linkages Manager 602.712.4574 Infrastructure Delivery and Operations Division (IDO) 602.712.7391 State Engineer, Sr. Deputy State Engineer and Deputy State Engineer Offices 602.712.7391 DISTRICT ENGINEERS Northcentral azdot.gov/business/district-contacts/northcentral 928.774.1491 Northeast azdot.gov/business/district-contacts/northeast 928.524.5400 Central Construction District azdot.gov/business/district-contacts/central 602.712.8965 Central Maintenance District azdot.gov/business/district-contacts/central 602.712.6664 Northwest azdot.gov/business/district-contacts/northwest 928.777.5861 -

The Maricopa County Wildlife Connectivity Assessment: Report on Stakeholder Input January 2012

The Maricopa County Wildlife Connectivity Assessment: Report on Stakeholder Input January 2012 (Photographs: Arizona Game and Fish Department) Arizona Game and Fish Department In partnership with the Arizona Wildlife Linkages Workgroup TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES ............................................................................................................................ i RECOMMENDED CITATION ........................................................................................................ ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ................................................................................................................. ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................ iii DEFINITIONS ................................................................................................................................ iv BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................................ 1 THE MARICOPA COUNTY WILDLIFE CONNECTIVITY ASSESSMENT ................................... 8 HOW TO USE THIS REPORT AND ASSOCIATED GIS DATA ................................................... 10 METHODS ..................................................................................................................................... 12 MASTER LIST OF WILDLIFE LINKAGES AND HABITAT BLOCKSAND BARRIERS ................ 16 REFERENCE MAPS ....................................................................................................................... -

Saddlebrooke Hiking Club Hike Database 11-15-2020 Hike Location Hike Rating Hike Name Hike Description

SaddleBrooke Hiking Club Hike Database 11-15-2020 Hike Location Hike Rating Hike Name Hike Description AZ Trail B Arizona Trail: Alamo Canyon This passage begins at a point west of the White Canyon Wilderness on the Tonto (Passage 17) National Forest boundary about 0.6 miles due east of Ajax Peak. From here the trail heads west and north for about 1.5 miles, eventually dropping into a two- track road and drainage. Follow the drainage north for about 100 feet until it turns left (west) via the rocky drainage and follow this rocky two-track for approximately 150 feet. At this point there is new signage installed leading north (uphill) to a saddle. This is a newly constructed trail which passes through the saddle and leads downhill across a rugged and lush hillside, eventually arriving at FR4. After crossing FR4, the trail continues west and turns north as you work your way toward Picketpost Mountain. The trail will continue north and eventually wraps around to the west side of Picketpost and somewhat paralleling Alamo Canyon drainage until reaching the Picketpost Trailhead. Hike 13.6 miles; trailhead elevations 3471 feet south and 2399 feet north; net elevation change 1371 feet; accumulated gains 1214 northward and 2707 feet southward; RTD __ miles (dirt). AZ Trail A Arizona Trail: Babbitt Ranch This passage begins just east of the Cedar Ranch area where FR 417 and FR (Passage 35) 9008A intersect. From here the route follows a pipeline road north to the Tub Ranch Camp. The route continues towards the corrals (east of the buildings).