Company Law Lawyers Innovation FINAL

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Series Limited Liability Company Instructions

Series Limited Liability Company Instructions Wyoming Secretary of State Herschler Building East, Suite 101 122 W 25th Street Cheyenne, WY 82002-0020 307.777.7311 [email protected] Before Filing Please Note: _________________________________________________________________ Pursuant to W.S. 17-29-108, the name must include the words “Limited Liability Company,” or its abbreviations “LLC,” “L.L.C.,” “Limited Company,” “LC,” “L.C.,” “Ltd. Liability Company,” “Ltd. Liability Co.,” or “Limited Liability Co.” If established, the names of each series must be listed in accordance with Chapter 5 of the Business Entities Rules. Under the circumstances specified in W.S. 17-28-104(e), an email address is required. Filing fee of $100.00 plus $10.00 for each series established. Visa or MasterCard payment available for online filings only. To file online, visit: https://wyobiz.wyo.gov. Make check or money order payable to Wyoming Secretary of State for paper filings. Annual reports are due every year on the first day of the anniversary month of formation. If not paid within 60 days of the due date the entity will be subject to dissolution. The limitations on liabilities must be set forth in the Operating Agreement and must be listed in your articles. Processing time is up to 15 business days following the date of receipt in our office. Please review the form prior to submission. The Secretary of State’s Office is unable to process incomplete forms. Additional Contact Information: ___________________________________________________________ Department of Revenue (Sales and Use Tax Information) o Ph. 307.777.5200 OR https://revenue.state.wy.us/ Wyoming Business Council (Licensing or Permit Information) o Ph. -

Doing Business in Norway

Doing Business in Norway 2020 Edition 1 Norway • Hammerfest • Tromsø 5.4 million Population • 119th most populous country on earth Constitutional monarchy Form of government • Constitution day: 17 May • Head of State: King Harald V • Prime Minister: Erna Solberg, conservative • Member of the EEA from 1 January 1994 • Member of the EU: No Oslo Capital of Norway • 5 regions • Highest mountain: Galdhøpiggen 2,469 m. • Largest lake: Mjøsa 365 sq.m. • The distance from Oslo to Hammerfest is as far as from Oslo to Athens Gross domestic product ca. NOK 3300 billion Economy • Trondheim • Currency: Krone (NOK) • GDP per capita: ca. NOK 615,000 • The largest source of income is the extraction and export of subsea oil and natural gas • Bergen Norway • Oslo • Stavanger ISBN2 978-82-93788-00-3 3 Contents 8 I Why invest in Norway 11 II Civil Law 23 III Business Entities 35 IV Acquisition Finance 43 V Real Estate 59 VI Energy 69 VII Employment 83 VIII Tax 103 IX Intellectual Property 113 X Public Procurement 121 XI Dispute Resolution 4 5 Norway is known for nature attractions like fjords, mountains, northern lights and the midnight sun. Because of the Gulf Stream, Norway has a friendlier climate than the latitude indicates, leaving it with ice-free ports all year round. The Gulf Stream is a warm ocean current leading water from the Caribbean north easterly across the Atlantic Ocean, and then follows the Norwegian coast northwards. 6 7 I. Why invest in Norway In spite of being a small nation, Norway is a highly developed and modern country with a very strong, open and buoyant economy. -

Study on Digitalisation of Company Law

STUDY ON DIGITALISATION OF COMPANY LAW By everis for the European Commission – DG Justice and Consumers Final Report (draft) Justice and Consumers 1 The information and views set out in this presentation are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official opinion of the Commission. The Commission does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this presentation. Neither the Commission nor any person acting on the Commission’s behalf may be held responsible for the use which may be made of the information contained therein. © European Union, 2017 Prepared By everis Brussels and Company Law experts: Dr. Antigoni Alexandropoulou Enrica Senini Geert Somers 2 MEMBER STATES REPORT MEMBER STATES REPORT 3 1 GLOSSARY 5 1.1 BELGIUM 8 1.2 CYPRUS 22 1.3 CZECH REPUBLIC 41 1.4 DENMARK 59 1.5 ESTONIA 72 1.6 FINLAND 93 1.7 FRANCE 118 1.8 GERMANY 132 1.9 GREECE 158 1.10 HUNGARY 176 1.11 POLAND 192 1.12 PORTUGAL 206 1.13 SPAIN 225 1.14 UNITED KINGDOM 248 3 4 DOCUMENT META DATA Property Value Release date 13.12.2017 Status: Final Version 3.2 Authors: everis Reviewed by: DG – JUST Approved by: 5 1 GLOSSARY Business registers – central, commercial and companies' registers established in all EU Member States in accordance with Directive 2009/101/EC. Company Law – legislation that regulates the creation, registration or incorporation, operation, governance, and dissolution of companies. Digitalisation of Company Law – changes in the Company law related procedures to move from paper-based processes where a physical presence before an authority is required, to end-to-end direct online ones; Registration – procedures for the registration of companies with the national authority in charge (usually the business register). -

ILLINOIS SERIES LLC's: Cost Effective Means to Limit Liability

ILLINOIS SERIES LLC'S: Cost Effective Means to Limit Liability Approximately two years ago, the Illinois Limited Liability Company Act was amended to allow for the creation of series limited liability companies ("Series LLCs"). Illinois followed Delaware, which introduced the Series LLC in 1996 in an effort to allow business owners to lower up-front costs and long term maintenance expenses for limited liability companies. While Series LLCs are widely used, especially within the real estate business sector, many business owners still do not know or understand the advantages of operating their business as a Series LLC. Like a corporation or a non-series limited liability company, a Series LLC is treated as a single legal entity. A Series LLC files a single annual report and pays a single annual fee. However, the "master" or "parent" Series LLC is permitted to form multiple or "subs" or "mini" limited liability companies under the framework of the master. Each sub formed under the master may have the same or different ownership and management structure. By electing to designate limited liability company as a Series LLC, a business owner may, at any time, form a sub by filing a registration of series with the Illinois Secretary of State. The up- front costs are a bit more than for a standard limited liability company, $750.00 compared to $500.00, but each registration of a new sub is only $50.00. Previously established limited liability companies may also be converted to a Series LLC by filing an article of amendment with the Illinois Secretary of State along with the appropriate filing fee. -

E-Commerce – New Opportunities, New Barriers

Kommerskollegium 2012:4 E-commerce – New Opportunities, New Barriers A survey of e-commerce barriers in countries outside the EU APP The National Board of Trade is the Swedish governmental tioning economy and for economic development. Our publica- agency responsible for issues relating to foreign trade and tions are the sole responsibility of the National Board of Trade. trade policy. Our mission is to promote an open and free trade with transparent rules. The basis for this task, given us by the The National Board of Trade also provides service to compa- Government, is that a smoothly functioning international trade nies, for instance through our Solvit Centre which assists com- and a further liberalized trade policy are in the interest of panies as well as people encountering trade barriers on the Sweden. To this end we strive for an efficient internal market, a internal market. The Board also administers The Swedish Trade liberalized common trade policy in the EU and an open and Procedures Council, SWEPRO. strong multilateral trading system, especially within the World Trade Organization (WTO). In addition, as an expert authority in trade policy issues, the National Board of Trade provides assistance to developing As the expert authority in trade and trade policy, the Board pro- countries, through trade-related development cooperation. We vides the Government with analyses and background material, also host Open Trade Gate Sweden, a one-stop information related to ongoing international trade negotiation as well as centre assisting exporters from developing countries with infor- more structural or long-term analyses of trade related issues. -

Series Limited Liability Company

A Series Limited Liability Company (Series LLC) is a form of entity that allows a single “master” LLC to partition its assets and liabilities among various cells known as Sub-LLCs. Each Sub-LLC may have different assets, operations, and/or investment objectives, and the members and managers, as well as their rights, obligations, and their sharing ratios, may be varied. The profits, losses, and liabilities of each Sub-LLC are legally separate from the other Sub-LLCs, which provides a liability shield between each Sub-LLC and the Series LLC. The Series LLC effectively creates a Parent/Subsidiary structure without requiring the administrative complexity and cost of creating “and managing multiple LLCs; the structure is similar to that of an S corporation with a Qualified Subchapter S Subsidiary (known as a QSUB). A Series LLC may be appropriate where a business has a variety of assets or operations that would benefit from liability protection from each other, or where multiple owners have different interests in the business or in different parts of the business operations. A Series LLC may be appropriate in various situations, such as: real estate development; oil and gas exploration; professional businesses; artists and musicians, manufacturing and distribution; hedge funds and private equity; or franchise businesses. The potential benefits of a Series LLC include reduced administrative costs and fewer state filings, liability protection for each Sub-LLC and the Series LLC, and the ease of adding or terminating individual Sub-LLCs. Additionally, distributions can be made from any Sub-LLC, and each Sub-LLC may have a different sharing ratio. -

Directors' Duties and Liabilities in Financial Distress During Covid-19

Directors’ duties and liabilities in financial distress during Covid-19 July 2020 allenovery.com Directors’ duties and liabilities in financial distress during Covid-19 A global perspective Uncertain times give rise to many questions Many directors are uncertain about their responsibilities and the liability risks The Covid-19 pandemic and the ensuing economic in these circumstances. They are facing questions such as: crisis has a significant impact, both financial and – If the company has limited financial means, is it allowed to pay critical suppliers and otherwise, on companies around the world. leave other creditors as yet unpaid? Are there personal liability risks for ‘creditor stretching’? – Can you enter into new contracts if it is increasingly uncertain that the company Boards are struggling to ensure survival in the will be able to meet its obligations? short term and preserve cash, whilst planning – Can directors be held liable as ‘shadow directors’ by influencing the policy of subsidiaries for the future, in a world full of uncertainties. in other jurisdictions? – What is the ‘tipping point’ where the board must let creditor interest take precedence over creating and preserving shareholder value? – What happens to intragroup receivables subordinated in the face of financial difficulties? – At what stage must the board consult its shareholders in case of financial distress and does it have a duty to file for insolvency protection? – Do special laws apply in the face of Covid-19 that suspend, mitigate or, to the contrary, aggravate directors’ duties and liability risks? 2 Directors’ duties and liabilities in financial distress during Covid-19 | July 2020 allenovery.com There are more jurisdictions involved than you think Guidance to navigating these risks Most directors are generally aware of their duties under the governing laws of the country We have put together an overview of the main issues facing directors in financially uncertain from which the company is run. -

19LSO-0059 V0.6 Series LLC Naming and Designation Requirements

2019 STATE OF WYOMING 19LSO-0059 Working Draft 0.6 DRAFT ONLY NOT APPROVED FOR INTRODUCTION HOUSE BILL NO. [BILL NUMBER] Series LLC naming and designation requirements. Sponsored by: HDraft Committee A BILL for 1 AN ACT relating to business entities; specifying that a series 2 limited liability company may be named or designated in any 3 manner; requiring registered agents to maintain series naming 4 or designation information; prohibiting the adoption of rules 5 relating to series naming or designation requirements and 6 filing requirements; requiring the repeal of specified rules; 7 making an appropriation; and providing for an effective date. 8 9 Be It Enacted by the Legislature of the State of Wyoming: 10 11 Section 1. W.S. 17-29-211 by creating new subsection 12 (o) is created to read: 13 1 [Bill Number] 2019 STATE OF WYOMING 19LSO-0059 Working Draft 0.6 1 17-29-211. Series of members, managers, transferable 2 interests or assets. 3 4 (o) A series may be named or designated in any manner 5 consistent with the operating agreement of the series or the 6 articles of organization of a limited liability company. The 7 secretary of state shall not adopt rules specifying naming or 8 designation requirements for series created under this 9 section. 10 11 Section 2. W.S. 17-28-107 is amended to read: 12 13 17-28-107. Duties of the registered agent; duties of 14 the entity. 15 16 (a) The registered agent shall: 17 18 (v) Maintain at the registered office, the 19 following information for each domestic entity represented 20 which shall be current within sixty (60) days of any change 21 until the entity's first annual report is accepted for filing 22 with the secretary of state and thereafter when the annual 2 [Bill Number] 2019 STATE OF WYOMING 19LSO-0059 Working Draft 0.6 1 report is due for filing and shall be maintained in a format 2 that can be reasonably produced on demand: 3 4 (D) Names or designations of each series 5 created under W.S. -

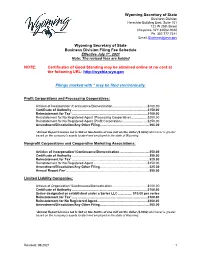

Wyoming Secretary of State Business Division Filing Fee Schedule Effective July 1St, 2021 Note: the Revised Fees Are Bolded

Wyoming Secretary of State Business Division Herschler Building East, Suite 101 122 W 25th Street Cheyenne, WY 82002-0020 Ph. 307.777.7311 Email: [email protected] Wyoming Secretary of State Business Division Filing Fee Schedule Effective July 1st, 2021 Note: The revised fees are bolded NOTE: Certificates of Good Standing may be obtained online at no cost at the following URL: http://wyobiz.wyo.gov Filings marked with * may be filed electronically. Profit Corporations and Processing Cooperatives: Articles of Incorporation*/Continuance/Domestication ....................................... $100.00 Certificate of Authority ....................................................................................$150.00 Reinstatement for Tax* ....................................................................................$100.00 Reinstatement for No Registered Agent (Processing Cooperative) ..................$200.00 Reinstatement for No Registered Agent (Profit Corporation) ............................$250.00 Amendment/Dissolution/Any Other Filing....................................................... $60.00 *Annual Report License tax is $60 or two-tenths of one mill on the dollar ($.0002) whichever is greater based on the company’s assets located and employed in the state of Wyoming. Nonprofit Corporations and Cooperative Marketing Associations: Articles of Incorporation*/Continuance/Domestication .................................$50.00 Certificate of Authority ......................................................................................$50.00 -

60,606,060 Ordinary Shares Goldman Sachs International BNP Paribas

Burrups Ltd Project: JC Decaux English Final No: 000000 Job Number/Filename: 633501_doc1.3d, Page: 1 of 104 0 Time: 16:42:46, Date: 22/06/01, BL: 0 SA (incorporated in France as a socie´ te´ anonyme) 60,606,060 Ordinary Shares This is an initial public offering of shares of JCDecaux SA. JCDecaux SA will offer 42,424,242 newly issued shares and certain of its shareholders will offer 18,181,818 existing shares. JCDecaux SA will not receive any proceeds from the sale of shares by the selling shareholders. This global offering includes a French retail offering (offre a` prix ouvert) of 2,500,423 shares, and an international offering to institutions of 58,105,637 shares. This offering circular relates only to the international offering outside of France. The French public offering is being made pursuant to a separate prospectus in the French language. Concurrently with the offering, JCDecaux SA is offering up to 1,136,363 additional newly issued shares reserved for its French employees. Prior to the global offering there has been no public market for the shares. The shares have been approved for listing on the Premier Marche´ of Euronext Paris S.A. See ‘‘Risk Factors’’ on page 17 of this offering circular for a discussion of certain factors to be considered in connection with an investment in the shares. Offering Price: E16.50 per share JCDecaux SA has granted the Underwriters (as listed later in this offering circular) warrants to purchase 9,090,909 additional shares. The warrants are exercisable for 30 days from the date of this offering circular, to cover over-allotments. -

Delaware Series Llc

MAJOR CHANGES TO THE DELAWARE SERIES LLC August 1, 2019 Lacee J. Wentworth, J.D. Associate, Handler Thayer, LLP Many lawyers advise their clients to form or incorporate their companies in Delaware due to, among other reasons, Delaware’s prestigious Court of Chancery that specializes in corporate law and resolving business disputes on an expedited basis without a jury. The high volume of cases in Delaware means a more predictable outcome for clients. In fact, many publicly traded companies and Fortune 500 companies have incorporated in Delaware regardless of their principal location. Since 1996 the Delaware Limited Liability Company Act (the “Act”) has allowed the formation of limited liability companies (“LLCs”) with or without series, having characteristics like that of a separate LLC. Each separate series can have separate members, managers, classes of limited liability interests, assets, business purpose and investment objectives. Under the Act, each series is treated as an entity separate from each other series of the same LLC and the LLC itself, which is often referred to as the “series LLC” or “master LLC.” Series LLCs A series LLC is an alternative business structure to forming multiple, independent LLCs to segregate and protect a company’s proposed assets. This novel business structure is often useful when utilized by family offices with multiple investment strategies and classes of assets, real estate investors who own several properties or companies that own multiple brands or other intellectual property. However, many lawyers and business owners do not form series LLCs due to many issues and challenges with the alternative business structure. -

Doing Business in France 2018

Doing business in France 2018 Moore Stephens Europe PRECISE. PROVEN. PERFORMANCE. Doing business in France 2018 Introduction The Moore Stephens Europe Doing Business In series of guides have been prepared by Moore Stephens member firms in the relevant country in order to provide general information for persons contemplating doing business with or in the country concerned and/or individuals intending to live and work in that country temporarily or permanently. Doing Business in France 2018 has been written for Moore Stephens Europe Ltd by COFFRA. In addition to background facts about France, it includes relevant information on business operations and taxation matters. This Guide is intended to assist organisations that are considering establishing a business in France either as a separate entity or as a subsidiary of an existing foreign company. It will also be helpful to anyone planning to come to France to work and live there either on secondment or as a permanent life choice. Unless otherwise noted, the information contained in this Guide is believed to be accurate as of 1 October 2018. However, general publications of this nature cannot be used and are not intended to be used as a substitute for professional guidance specific to the reader’s particular circumstances. Moore Stephens Europe Ltd provides the Regional Executive Office for the European Region of Moore Stephens International. Founded in 1907, Moore Stephens International is one of the world’s major accounting and consulting networks comprising 271 independently owned and managed firms and 614 offices in 112 countries around the world. Our member firms’ objective is simple: to be viewed as the first point of contact for all our clients’ financial, advisory and compliance needs.