Berkson on Diamond.Pages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Frank O'hara As a Visual Artist Daniella M

Student Publications Student Scholarship Spring 2018 Fusing Both Arts to an Inseparable Unity: Frank O'Hara as a Visual Artist Daniella M. Snyder Gettysburg College Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship Part of the American Art and Architecture Commons, Art and Design Commons, and the Theory and Criticism Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Snyder, Daniella M., "Fusing Both Arts to an Inseparable Unity: Frank O'Hara as a Visual Artist" (2018). Student Publications. 615. https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship/615 This open access student research paper is brought to you by The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The uC pola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Fusing Both Arts to an Inseparable Unity: Frank O'Hara as a Visual Artist Abstract Frank O’Hara, a curator at the Museum of Modern Art in New York and a published poet in the 1950s and 60s, was an exemplary yet enigmatic figure in both the literary and art worlds. While he published poetry, wrote art criticism, and curated exhibitions—on Franz Kline, Robert Motherwell, and Jackson Pollock—he also collaborated on numerous projects with visual artists, including Larry Rivers, Michael Goldberg, Grace Hartigan, Joe Brainard, Jane Freilicher, and Norman Bluhm. Scholars who study O’Hara fail to recognize his work with the aforementioned visual artists, only considering him a “Painterly Poet” or a “Poet Among Painters,” but never a poet and a visual artist. Through W.J.T. Mitchell’s “imagetext” model, I apply a hybridized literary and visual analysis to understand O’Hara’s artistic work in a new way. -

Late Modernist Poetics and George Schneeman's Collaborations with the New York School Poets

Timothy Keane Studies in Visual Arts and Communication: an international journal Vol 1, No 2 (2014) on-line ISSN 2393 - 1221 No Real Assurances: Late Modernist Poetics and George Schneeman’s Collaborations with the New York School Poets Timothy Keane City University of New York Abstract: Painter George Schneeman’s collaborations with the New York School poets represent an under-examined, vast body of visual-textual hybrids that resolve challenges to mid-and-late century American art through an indirect alliance with late modernist literary practices. Schneeman worked with New York poets intermittently from 1966 into the early 2000s. This article examines these collagist works from a formalist perspective, uncovering how they incorporate gestural techniques of abstract art and the poetic use of juxtaposition, vortices, analogies, and pictorial and lexical imagism to generate non-representational, enigmatic assemblages. I argue that these late modernist works represent an authentically experimental form, violating boundaries between art and writing, disrupting the venerated concept of single authorship, and resisting the demands of the marketplace by affirming for their creators a unity between art-making and daily life—ambitions that have underpinned every twentieth century avant-garde movement. On first seeing George Schneeman’s painting in the 1960s, poet Alice Notley asked herself, “Is this [art] new? Or old fashioned?”1 Notley was probably reacting to Schneeman’s unassuming, intimate representations of Tuscan landscape and what she called their “privacy of relationship.” The potential newness Notley detected in Schneeman’s “old-fashioned” art might be explained by how his small-scale and quiet paintings share none of the self-conscious flamboyance in much American painting of the 1960s and 1970s. -

Download Program Notes

Friday November 17th, 2006 “As the Great Earth Rolls On” A Frank O’Hara 80th Birthday Celebration in words and moving pictures Presented by San Francisco Cinematheque & The Poetry Center, San Francisco State University Bill Berkson speaks and reads Frank O’Hara’s “In Memory of My Feelings.” Frank O’Hara: NET Outtake Series (1966), 16mm film on DVD, 34 min. courtesy American Poetry Archives, The Poetry Center, SFSU One in a series of edited outtakes from the National Educational Television program titled USA: Poetry, produced by KQED television from 1965-66 by Gordon Craig, Richard O. Moore and associates. Among the only film footage of Frank O’Hara (27 Mar. 1926-25 July 1966), who was killed in an accident later the same year at age 40, the program was shot March 5, 1966 at O’Hara’s apartment at 791 Broadway, on the street in Manhattan, and in painter Alfred Leslie’s studio at 92 Broadway. Together they collaborate on the dialogue for a film Leslie is making titled Philosophy in the Bedroom, the notes for which were later destroyed by a fire at Leslie’s studio. O’Hara reads several poems, including Liebeslied, An Airplane Whistle (After Heine), Ave Maria (beginning “Mothers of America, let your kids go to the movies”), Answer to Voznesensky and Yevtushenko, and For the Chinese New Year & For Bill Berkson. i n t e r m i s s i o n The Trouble with Paradise: a neo-benshi tribute by Mac McGinnes, read by Julian T. Brolaski and Dan Fisher. The dialog from one of O’Hara’s favorite films, Trouble in Paradise (1932), directed by Ernst Lubitsch, starring Miram Hopkins, Herbert Marshall, et al., is subverted using the poet’s own lines. -

The Poetry Project Newsletter

THE POETRY PROJECT NEWSLETTER $5.00 #212 OCTOBER/NOVEMBER 2007 How to Be Perfect POEMS BY RON PADGETT ISBN: 978-1-56689-203-2 “Ron Padgett’s How to Be Perfect is. New Perfect.” —lyn hejinian Poetry Ripple Effect: from New and Selected Poems BY ELAINE EQUI ISBN: 978-1-56689-197-4 Coffee “[Equi’s] poems encourage readers House to see anew.” —New York Times The Marvelous Press Bones of Time: Excavations and Explanations POEMS BY BRENDA COULTAS ISBN: 978-1-56689-204-9 “This is a revelatory book.” —edward sanders COMING SOON Vertigo Poetry from POEMS BY MARTHA RONK Anne Boyer, ISBN: 978-1-56689-205-6 Linda Hogan, “Short, stunning lyrics.” —Publishers Weekly Eugen Jebeleanu, (starred review) Raymond McDaniel, A.B. Spellman, and Broken World Marjorie Welish. POEMS BY JOSEPH LEASE ISBN: 978-1-56689-198-1 “An exquisite collection!” —marjorie perloff Skirt Full of Black POEMS BY SUN YUNG SHIN ISBN: 978-1-56689-199-8 “A spirited and restless imagination at work.” Good books are brewing at —marilyn chin www.coffeehousepress.org THE POETRY PROJECT ST. MARK’S CHURCH in-the-BowerY 131 EAST 10TH STREET NEW YORK NY 10003 NEWSLETTER www.poetryproject.com #212 OCTOBER/NOVEMBER 2007 NEWSLETTER EDITOR John Coletti WELCOME BACK... DISTRIBUTION Small Press Distribution, 1341 Seventh St., Berkeley, CA 94710 4 ANNOUNCEMENTS THE POETRY PROJECT LTD. STAFF ARTISTIC DIRECTOR Stacy Szymaszek PROGRAM COORDINATOR Corrine Fitzpatrick PROGRAM ASSISTANT Arlo Quint 6 WRITING WORKSHOPS MONDAY NIGHT COORDINATOR Akilah Oliver WEDNESDAY NIGHT COORDINATOR Stacy Szymaszek FRIDAY NIGHT COORDINATOR Corrine Fitzpatrick 7 REMEMBERING SEKOU SUNDIATA SOUND TECHNICIAN David Vogen BOOKKEEPER Stephen Rosenthal DEVELOpmENT CONSULTANT Stephanie Gray BOX OFFICE Courtney Frederick, Erika Recordon, Nicole Wallace 8 IN CONVERSATION INTERNS Diana Hamilton, Owen Hutchinson, Austin LaGrone, Nicole Wallace A CHAT BETWEEN BRENDA COULTAS AND AKILAH OLIVER VOLUNTEERS Jim Behrle, David Cameron, Christine Gans, HR Hegnauer, Sarah Kolbasowski, Dgls. -

Part of His History 1944-2020 by Steve Clay Originally Published in the Brooklyn Rail Dec 20 – Jan 21, 2021 Issue

IN MEMORIAM Lewis Warsh: Part of His History 1944-2020 By Steve Clay Originally published in The Brooklyn Rail Dec 20 – Jan 21, 2021 Issue Working with Lewis Warsh was always an effortless pleasure and indistinguishable from our friendship. I first met him in Brooklyn in 1995, introduced by Mitch Highfill. We spoke about his archive and collection of rare books he wanted to sell, and arranged to meet at his apartment. During that visit I looked at his treasures, among which was a small book he'd assembled by hand when he found a set of black and white photographs taken in 1968, primarily on Bustin's Island, Maine and in Bolinas, California. The photographs were classic family-style vacation snapshots of Lewis and Anne Waldman, Ted, Sandy, and Kate Berrigan, Tom, Angelica, and baby Juliet Clark, Joanne Kyger, Jack Boyce, and others. Lewis had mounted the photos into a store- bought hardcover photo book, then typed captions and placed them across from the pictures: The front cover read Bustin's Island '68. I immediately proposed that Granary Books publish Portrait of Lewis Warsh, pencil on paper by Phong H. Bui. an edition. I was impressed with the spontaneity of the photographs and the sincerity of the writing. They gave me a private glimpse into a community of poets whose work and stories I knew but was now seeing in their formative years as friends and collaborators. It's a remarkably lucid portrait of a time and place. The captions, written 28 years after the fact, brought perspective to the changes during the intervening years. -

“Why I Am Not a Painter”: Frank O’Hara, Art, Poetry, & Criticism

ARTHI 5770 / MFA 5070 “Why I Am Not a Painter”: Frank O’Hara, Art, Poetry, & Criticism David Getsy, Art History, Theory & Criticism [email protected] Terry R. Myers, Painting & Drawing, [email protected] School of the Art Institute of Chicago Fall 2012 graduate seminar Thursdays 1-4pm, MC1501 Course Description The seminar will examine the artistic culture of the 1950s and 60s through the pivotal and contradictory role of the poet and MoMA curator Frank O’Hara. Central to the history of American poetry but often overlooked in his importance to modernist art criticism, O’Hara established a hybrid practice based on blurred boundaries. Focusing on his collaborations with artists, the seminar will provide an in-depth analysis of O’Hara’s multiple practices including poetry, art criticism, and curation. Emphasis will be placed on his relation to Abstract Expressionism, and his cultivation of such artists as Larry Rivers, Jasper Johns, and Elaine de Kooning. Through O’Hara’s example, we will seek to address the difficulties, pleasures, and rewards of bringing the visual and the verbal into intimate contact; and we will consider his unique position as a poet, Elaine de Kooning, Frank O’Hara, 1962 critic, curator, and visual collaborator as a pioneering model for today. Course Structure Each three-hour session will focus on the presentation and discussion of required texts and student research. Students will be evaluated on the basis of their preparation, attendance, and critical engagement with course readings and concepts in addition to formal written assignments. There is one required textbook: Donald Allen, ed., The Collected Poems of Frank O’Hara (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995) All other readings will be made available via the course homepage on the SAIC portal. -

Bernadette Mayer Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf0199n71x No online items Bernadette Mayer Papers Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego Copyright 2019 9500 Gilman Drive La Jolla 92093-0175 [email protected] URL: http://libraries.ucsd.edu/collections/sca/index.html Bernadette Mayer Papers MSS 0420 1 Descriptive Summary Languages: English Contributing Institution: Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego 9500 Gilman Drive La Jolla 92093-0175 Title: Bernadette Mayer Papers Identifier/Call Number: MSS 0420 Physical Description: 30.0 Linear feet(70 archives boxes, 1 card file box and 7 oversize file folders) Date (inclusive): 1958-2017 Abstract: Papers of Bernadette Mayer, writer, teacher, editor, and publisher. Most often associated with the New York School, Mayer uses compositional methods such as chance operations, collage and cut-up. Materials include correspondence with writers, artists, publishers, and friends; manuscripts and typescripts; notebooks and loose notes; teaching notes; audio recordings and photographs; and biographical materials such as calendars, datebooks and ephemera. Scope and Content of Collection The Bernadette Mayer Papers document Mayer's career as a writer and teacher and, to a lesser extent, her career as a publisher and editor. Additionally, the papers reflect the broader community of artists and writers known as the New York School. Materials include correspondence from writers, artists, publishers, and friends; notebooks and loose notes; manuscripts and typescripts of Mayer's works; teaching notes; audio recordings and photographs; and biographical materials such as calendars, datebooks and ephemera. Accession Processed in 1998 Arranged in eleven series: 1) BIOGRAPHICAL MATERIAL, 2) CORRESPONDENCE, 3) WRITINGS, 4) NOTEBOOKS, 5) WRITINGS OF OTHERS, 6) TEACHING MATERIAL, 7) EDITING MATERIAL, 8) EPHEMERA, 9) PHOTOGRAPHS, 10) SOUND RECORDINGS, and 11) ORIGINALS OF PRESERVATION PHOTOCOPIES. -

Joanne Kyger and the Aesthetics of Attention

Joanne Kyger and the Aesthetics of Attention Terence Diggory Skidmore College In the popular mind Beat writing is expressionist, a “howl” of agony or an exclamation of ecstasy. Emotion is projected, expressed from the writer into the world. The attention of the reader or listener is directed to the writer as the source of what is expressed, so the person of Allen Ginsberg or Jack Kerouac, for instance, becomes as famous as his writing. Joanne Kyger, the subject of this paper, is not famous in this way. The fact that she is a woman has tended to keep her on the margins of the homosocial network of Beat writers, as recent critics, including my fellow panelists, Linda Russo and Amy Friedman, have noted. But Kyger’s writing practice also tends to direct attention away from the writer onto the world in which the writer is situated. “Being me” seems less urgent to Kyger than “being there,” the phrase that both Michael Davidson (88) and Linda Russo (“Introduction”) cite to characterize Kyger’s work. The phrase “being there” appears in a sequence entitled Joanne (1970), and that title makes clear that Kyger is not wholly detached from the concept of personal identity. But she writes, “I wasn’t built in a day” (About Now 196). The sequence Joanne, like much of her later work, gives the impression of a self being built during the writing process rather than a preexisting self being expressed through the writing. Individual moments of perception supply the building blocks, and each moment is equally capable of making or unmaking what has preceded it. -

248-Newsletter.Pdf

The Poetry Project October / november 2016 Issue #248 The Poetry Project October / November 2016 Issue #248 Director: Stacy Szymaszek Managing Director: Nicole Wallace Archivist: Will Edmiston Program Director: Simone White Archival Assistant: Marlan Sigelman Communications & Membership Coordinator: Laura Henriksen Bookkeeper: Carlos Estrada Newsletter Editor: Betsy Fagin Workshop/Master Class Leaders (Fall 2016): Krystal Reviews Editor: Sara Jane Stoner Languell, Trace Peterson, Brenda Coultas, Miyung Mi Kim Monday Night Readings Coordinator: Judah Rubin Box Office Staff: Micaela Foley, Cori Hutchinson, and Wednesday Night Readings Coordinator: Simone White Catherine Vail Friday Night Readings Coordinator: Ariel Goldberg Interns: Shelby Cook, Iris Dumaual, and Cori Hutchinson Friday Night Readings Assistant: Yanyi Luo Newsletter Consultant: Krystal Languell Volunteers Damla Bek, Reynaldo Carrasco, Mel Elberg, Micaela Foley, Hadley Gitto, Cori Hutchinson, Anna Kreienberg, Phoebe Lifton, Dave Morse, Batya Rosenblum, Erkinaz Shuminov, Viktorsha Uliyanova, Shanxing Wang, and Emma Wippermann. Board of Directors Camille Rankine (Chair), Katy Lederer (Vice-Chair), Carol Overby (Treasurer), and Kristine Hsu (Secretary), Todd Colby, Adam Fitzgerald, Boo Froebel, John S. Hall, Erica Hunt, Jonathan Morrill, Elinor Nauen, Laura Nicoll, Purvi Shah, Jo Ann Wasserman, and David Wilk. Friends Committee Brooke Alexander, Dianne Benson, Will Creeley, Raymond Foye, Michael Friedman, Steve Hamilton, Viki Hudspith, Siri Hustvedt, Yvonne Jacquette, Gillian McCain, Eileen Myles, Patricia Spears Jones, Michel de Konkoly Thege, Greg Masters, Ron Padgett, Bob Holman, Paul Slovak, John Yau, Anne Waldman and Hal Willner. Funders The Poetry Project is very grateful for the continued support of our funders Axe-Houghton Foundation; Committee on Poetry; Dr. Gerald J. & Dorothy R. Friedman Foundation, Inc.; Jerome Foundation; Leaves of Grass Fund; Leslie Scalapino – O Books Fund; LitTAP; New York Council for the Humanities; Poets & Writers, Inc.; Poets for the Planet Fund; The Robert D. -

Moma's FALL 2006 SEASON of ADULT and ACADEMIC PROGRAMS EXPLORE WIDE VARIETY of TOPICS RELATED to MODERN and CONTEMPORARY ART I

MoMA’S FALL 2006 SEASON OF ADULT AND ACADEMIC PROGRAMS EXPLORE WIDE VARIETY OF TOPICS RELATED TO MODERN AND CONTEMPORARY ART IN TOURS, LECTURES, AND COURSES Lewis B. and Dorothy Cullman Education and Research Building Opening November 28 Symposium Explores The Feminist Future on January 26 and 27 New York, October 12, 2006—MoMA’s fall adult and academic programs explore the visual and intellectual complexity of modern and contemporary art through programs that are accessible to audiences of various levels and backgrounds. A variety of educational formats— courses, lectures, conversations, symposia, and poetry readings—use MoMA’s collection and special exhibitions as a point of focus. Participants gain insight through firsthand observations and discussions with distinguished experts, artists, writers, and MoMA curators and educators. Many of the programs will take place in the new Lewis B. and Dorothy Cullman Education and Research Building, which will open on November 28, 2006, marking the completion of The Museum of Modern Art's expansion and renovation project. Designed by Yoshio Taniguchi, the new building serves as a vital link between the Museum and its diverse and expanding audiences, and broadens access to the Museum's extensive educational resources, underscoring the integral relationships between education and other departments at MoMA. ADULT AND ACADEMIC PROGRAMS SCHEDULE.......................................................... 1 Special Exhibition Programs.................................................................................. -

R in 1963 Frank O'hara Threw a Party for Edwin Denby's Sixtieth Birthday. the Invitation Was Printed with an Acrostic Poem B

EDWIN DENBY’S NEW YORK SCHOOL MARY MAXWELL In 1963 Frank O’Hara threw a party for Edwin Denby’s sixtieth birthday. The invitation was printed with an acrostic poem by O’Hara entitled ‘‘Edwin’s Hand.’’ The first stanzas read: Easy to love, but di≈cult to please, he walks densely as a child in the midst of spectacular needs to understand. Desire makes our enchanter gracious, and naturally he’s surprised to be. And so are you to be you, when he smiles. At O’Hara’s funeral three years later (a gathering at which Larry Rivers announced that ‘‘there are at least sixty people in New York who thought Frank O’Hara was their best friend’’), Denby was the first friend to speak, ‘‘standing Lincoln-like and low-voiced under the big elm at Springs,’’ according to Bill Berkson. Of O’Hara’s R 65 66 MAXWELL sudden death, Denby later said, ‘‘Some people never recovered; in ways, I never did.’’ One of the ways Denby did not recover (though he himself would never have said so) was that as a poet, he had lost his most important advocate. His first collection of poems, In Public, in Private, for example, had been praised by O’Hara in 1957 as ‘‘an increasingly important book for the risks it takes in successfully establishing a specifically American spoken diction which has a classical firmness and clarity under his hand.’’ And though Denby is still universally lauded as the most important and influential American dance critic of the twentieth century, he remains rela- tively unknown as a poet beyond a small group of enthusiasts. -

Introduction

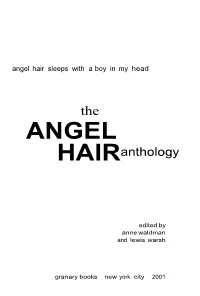

angel hair sleeps with a boy in my head the ANGEL anthology HAIR edited by anne waldman and lewis warsh granary books new york city 2001 INTRODUCTION ANNE WALDMAN I met Lewis Warsh at the Berkeley Poetry Conference and will always forever after think we founded Angel Hair within that auspicious moment. Conflation of time triggered by romance adjacent to the glam• orous history-making events of the confer• ence seems a reasonable explanation. Perhaps Angel Hair was what we made together in our brief substantive marriage that lasted and had repercussions. And sped INTRODUCTION us on our way as writers. Aspirations to be a poet were rising, the ante grew higher at LEWIS WARSH Berkeley surrounded by heroic figures of the New American Poetry. Here was a fellow Anne Waldman and I met in the earliest New Yorker, same age, who had also written stages of our becoming poets. Possibly edit• novels, was resolute, erudite about contem• ing a magazine is a tricky idea under these porary poetry. Mutual recognition lit us up. circumstances. Possibly it's the best idea-to Don't I know you? test one's ideas before you even have them, Summer before last year at Bennington or when they're pre-embryonic. In a sense where I'd been editing SILO magazine doing a magazine at this early moment was under tutalage of printer-poet Claude our way of giving birth-as much to the Fredericks, studying literature and poetry actual magazine and books as to our selves as with Howard Nemerov and other literary poets.