The Secret – Dani Alves Article from – the Players Tribune

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uefa Champions League

UEFA CHAMPIONS LEAGUE - 2020/21 SEASON MATCH PRESS KITS Camp Nou - Barcelona Tuesday 8 December 2020 21.00CET (21.00 local time) FC Barcelona Group G - Matchday 6 Juventus Last updated 03/12/2020 15:29CET UEFA CHAMPIONS LEAGUE OFFICIAL SPONSORS Match-by-match lineups 2 Legend 4 1 FC Barcelona - Juventus Tuesday 8 December 2020 - 21.00CET (21.00 local time) Match press kit Camp Nou, Barcelona Match-by-match lineups FC Barcelona UEFA Champions League - Group stage Group G Club Pld W D L GF GA Pts FC Barcelona 5 5 0 0 16 2 15 Juventus 5 4 0 1 11 4 12 FC Dynamo Kyiv 5 0 1 4 3 13 1 Ferencvárosi TC 5 0 1 4 5 16 1 Matchday 1 (20/10/2020) FC Barcelona 5-1 Ferencvárosi TC Goals: 1-0 Messi 27 (P) , 2-0 Fati 42, 3-0 Coutinho 52, 3-1 Kharatin 70 (P) , 4-1 Pedri 82, 5-1 Dembélé 89 FC Barcelona: Neto, Dest, Piqué, Pjanić (76 Sergio Busquets), Messi, Coutinho (70 Ronald Araújo), Lenglet, Francisco Trincão (63 Dembélé), Sergi Roberto (62 Junior Firpo), F. de Jong, Fati (63 Pedri) Matchday 2 (28/10/2020) Juventus 0-2 FC Barcelona Goals: 0-1 Dembélé 14, 0-2 Messi 90+1 (P) FC Barcelona: Neto, Ronald Araújo (46 Sergio Busquets), Griezmann (89 Junior Firpo), Pjanić, Messi, Dembélé (66 Fati), Lenglet, Pedri (92 Braithwaite), Jordi Alba, Sergi Roberto, F. de Jong Matchday 3 (04/11/2020) FC Barcelona 2-1 FC Dynamo Kyiv Goals: 1-0 Messi 5 (P) , 2-0 Piqué 65, 2-1 Tsygankov 75 FC Barcelona: Ter Stegen, Dest, Piqué, Sergio Busquets (74 Lenglet), Griezmann (60 Dembélé), Pjanić (60 Sergi Roberto), Messi, Pedri (83 Aleñá), Jordi Alba, F. -

Report Player in Match

Spain. Super Cup 13.08.2017 Barcelona 1-3 Real Madrid Barcelona 1-3 Real Madrid Player actions data 2 1. Marc-Andre ter Stegen Player action spots Direction of passes Per match 1st half 2nd half ACTIONS DURING THE MATCH 1st half 2nd half INSTAT INDEX 257 - - Minutes played 93 - - 1 Actions / successful 36 / 30 83% 15 / 13 87% 21 / 17 81% 0% Shots / on target - - - Fouls - - - 7 8 7 5 6 Fouls committed / suffered - - - 3 15 30 45 60 75 90 PASSES / ACCURATE 24 / 22 92% 11 / 9 82% 13 / 13 100% Player's actions 0 Team actions non-attacking / accurate 10 / 10 100% 5 / 5 100% 5 / 5 100% 0% attacking / accurate 14 / 12 86% 6 / 4 67% 8 / 8 100% key / accurate - - - INSTAT INDEX forward / accurate 24 / 22 92% - - back / accurate - - - 34 to the right / accurate 11 / 10 91% - - 293 294 100% to the left / accurate 13 / 12 92% - - 296 265 into the box / accurate - - - 264 257 15 30 45 60 75 90 1 30 4 crosses / accurate - - - 100% 97% 100% InStat Index player's condition at every 5 minutes accurate inaccurate long / accurate 4 / 3 75% - - InStat Index team's condition at every 5 minutes Successful actions Unsuccessful actions CHALLENGES / WON - - - defensive / won - - - attacking / won - - - Challenges Passes distribution air / won - - - tackles / successful - - - 1 Keylor Navas - - 18 Jordi Alba 2 2 4 dribbles / successful - - - 12 Marcelo - - 23 Umtiti 6 7 13 0 4 Sergio Ramos - - 3 Pique 1 3 4 Interceptions / in opp. half 3 / 0 - 3 / 0 0% 5 Varane - - 22 Aleix Vidal 3 1 4 Picking up free balls / in opp. -

Who Can Replace Xavi? a Passing Motif Analysis of Football Players

Who can replace Xavi? A passing motif analysis of football players. Javier Lopez´ Pena˜ ∗ Raul´ Sanchez´ Navarro y Abstract level of passing sequences distributions (cf [6,9,13]), by studying passing networks [3, 4, 8], or from a dy- Traditionally, most of football statistical and media namic perspective studying game flow [2], or pass- coverage has been focused almost exclusively on goals ing flow motifs at the team level [5], where passing and (ocassionally) shots. However, most of the dura- flow motifs (developed following [10]) were satis- tion of a football game is spent away from the boxes, factorily proven by Gyarmati, Kwak and Rodr´ıguez passing the ball around. The way teams pass the to set appart passing style from football teams from ball around is the most characteristic measurement of randomized networks. what a team’s “unique style” is. In the present work In the present work we ellaborate on [5] by ex- we analyse passing sequences at the player level, us- tending the flow motif analysis to a player level. We ing the different passing frequencies as a “digital fin- start by breaking down all possible 3-passes motifs gerprint” of a player’s style. The resulting numbers into all the different variations resulting from labelling provide an adequate feature set which can be used a distinguished node in the motif, resulting on a to- in order to construct a measure of similarity between tal of 15 different 3-passes motifs at the player level players. Armed with such a similarity tool, one can (stemming from the 5 motifs for teams). -

P18 Layout 1

TUESDAY, APRIL 29, 2014 SPORTS Outrage over banana insult to footballer in Spain BARCELONA: A storm over racism in Villareal ground by certain people at the ums and the continental and global bod- Spanish football erupted yesterday after a game,” the club said in a statement. ies, UEFA and FIFA, have tried to launch fan threw a banana at Barcelona full-back Barcelona welcomed the condemna- campaigns. In November last year, FIFA Dani Alves, with Brazilian President Dilma tion of the banana insult by Villareal, which president Sepp Blatter said he was “sick- Rousseff joining widespread outrage. sent a message on Twitter after the game ened” to see some Real Betis supporters A spectator threw the banana onto the saying: “Pity to see an ignoramus capable make monkey chants at their own player, pitch near the 30-year-old Brazilian inter- of such a lamentable act. There is no room Brazilian defender Paulao, in a city derby national as his star-studded side played at for it in sport and even less in our club.” against Sevilla. Villareal on Sunday night. Villareal’s reaction was a move in the Earlier in the season, two Elche fans Alves won praise for his reaction, pick- right direction towards “converting were fined 4,000 euros ($5,400) and ing up the banana to take a bite before grounds into areas where sports take pri- banned from attending sporting events for going on with game and setting up a goal ority and where the bad behavior by some 12 months for racially abusing Granada in Barcelona’s dramatic come-from-behind people is, first, isolated and then, eradicat- defender Allan-Romeo Nyom. -

Brilliant Brazil Sizzle to First Copa Title in Over 10 Years

14 Tuesday, July 9, 2019 Sports Quick read PSG to take action Brilliant Brazil sizzle to first after Neymar skips training FRENCH champions Paris Saint- Germain have said they will take action against Neymar after the Copa title in over 10 years Brazilian forward failed to report for training on Monday. The 27-year-old is a reported target for Barcelona, whose President Josep Maria Bartomeu said last week that Neymar wanted to leave the Ligue 1 side to return to Spain, but that PSG were reluctant to sell him. Neymar joined PSG from Barcelona for a world record 222 million euros in 2017. “On Monday, July 8, Neymar was due to return to pre-season activities with the Paris St Ger- main senior squad,” PSG said in a statement on their website. “Paris St Germain notes that Neymar was not in attendance at the agreed time and place. This was without the club’s prior au- Peru’s fans react in Lima after their team lost the Copa America thorisation. The club regrets this final. Ten-man Brazil held on to win on home soil despite Gabriel situation and will therefore take Jesus’s dismissal during their 3-1 victory over Peru. (AFP) appropriate action.” (REUTERS) Peru pushed forward in the first for coach Tite, who took second half and were thrown a charge three years ago. Brazil coach Tite lifeline with 20 minutes remain- They also did it without slams Messi after ing when Jesus was sent off. Neymar, who was injured on ‘corruption’ claims He had been felled by Car- the eve of the tournament. -

Uefa Champions League

UEFA CHAMPIONS LEAGUE - 2016/17 SEASON MATCH PRESS KITS Estadio Ramón Sánchez Pizjuán - Seville Tuesday 22 November 2016 Sevilla FC 20.45CET (20.45 local time) Juventus Group H - Matchday 5 Last updated 28/08/2017 19:57CET UEFA CHAMPIONS LEAGUE OFFICIAL SPONSORS Previous meetings 2 Match background 7 Squad list 9 Head coach 11 Match officials 12 Fixtures and results 14 Match-by-match lineups 18 Competition facts 20 Team facts 21 Legend 23 1 Sevilla FC - Juventus Tuesday 22 November 2016 - 20.45CET (20.45 local time) Match press kit Estadio Ramón Sánchez Pizjuán, Seville Previous meetings Head to Head UEFA Champions League Date Stage Match Result Venue Goalscorers 14/09/2016 GS Juventus - Sevilla FC 0-0 Turin UEFA Champions League Date Stage Match Result Venue Goalscorers 08/12/2015 GS Sevilla FC - Juventus 1-0 Seville Llorente 65 30/09/2015 GS Juventus - Sevilla FC 2-0 Turin Morata 41, Zaza 87 Home Away Final Total Pld W D L Pld W D L Pld W D L Pld W D L GF GA Sevilla FC 1 1 0 0 2 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 3 1 1 1 1 2 Juventus 2 1 1 0 1 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 3 1 1 1 2 1 Sevilla FC - Record versus clubs from opponents' country UEFA Europa League Date Stage Match Result Venue Goalscorers 0-2 Bacca 22, Daniel 14/05/2015 SF ACF Fiorentina - Sevilla FC Florence agg: 0-5 Carriço 27 Aleix Vidal 17, 52, 07/05/2015 SF Sevilla FC - ACF Fiorentina 3-0 Seville Gameiro 75 UEFA Cup Date Stage Match Result Venue Goalscorers 18/12/2008 GS UC Sampdoria - Sevilla FC 1-0 Genoa Bottinelli 75 UEFA Super Cup Date Stage Match Result Venue Goalscorers F. -

Brazil Destroys Uruguay, Argentina Survives

Tomic pulls out at SportsSports Miami with injury 43 SATURDAY,MARCH 25, 2017 SATURDAY,MARCH BUENOS AIRES: Argentina’s forward Lionel Messi (2nd-R) vies for the ball with Chile’s midfielder Charles Aranguiz (C) during their 2018 FIFA World Cup qualifier football match at the Monumental stadium in Buenos Aires, Argentina, on Thursday. — AFP Brazil destroys Uruguay, Argentina survives SAO PAULO: Brazil was not intimidated by also needed a penalty to score a 1-0 home vic- but Brazil was countering dangerously. On 74 ference. Uruguay resented the absence of sus- more than 60,000 raucous fans at the Estadio tory against Bolivia. Elsewhere, seventh-place minutes, Neymar’s genius appeared. After pended targetman Luis Suarez, while Brazil Centenario in Montevideo, beating second- Paraguay beat fifth-place Ecuador 2-1 and bot- defender Miranda cleared the ball from his missed teenage sensation Gabriel Jesus, who place Uruguay 4-1 in South America’s World tom team Venezuela drew 2-2 with eighth- box, the Barcelona star beat Uruguayan Coates has a broken toe. Brazil will miss defender Dani Cup qualifying group to retain the lead in the place Peru. in a quick race and lobbed Silva to make it 3-1 Alves in the clash against Paraguay on Tuesday standings after 13 matches. Midfielder and score his first goal against Uruguay. By in Sao Paulo the match that will likely secure its Paulinho scored a surprising hat trick, with BRAZIL then the Montevideo stadium, which hosted spot in the next World Cup. Uruguay will travel Barcelona star Neymar adding another, to keep For the first time since September, a team the 1930 World Cup final, sounded more like to face Peru. -

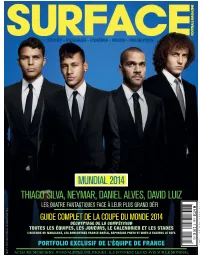

Thiago Silva, Neymar, Daniel Alves, David Luiz Luiz David Alves, Daniel Neymar, Silva, Thiago

N°30 -JUIN-JUILET - 2014 3’:HIKORC=ZUX^U]:?a@k@n@a@fM 04725 - 30H - F: 3,90 E - RD "; MUNDIAL 2014 DÉCRYPTAGE DE LA COMPÉTITION DÉCRYPTAGE LES FANTASTIQUES À LEUR PLUS QUATRE FACE GRAND DÉFI GUIDE COMPLET DE LA COUPE DU MONDE 2014 PORTFOLIO EXCLUSIF DE L’ÉQUIPE DE FRANCE EXCLUSIF DE L’ÉQUIPE PORTFOLIO TOUTES LES ÉQUIPES, LES JOUEURS, LE CALENDRIER ET LES STADES LES JOUEURS, TOUTES LES ÉQUIPES, L’HISTOIRE DU MARACANÃ, LES RENCONTRES FRANCE-BRÉSIL, REPORTAGE PHOTO ET VIDÉO À TRAVERS LE PAYS TRAVERS VIDÉO À PHOTO ET REPORTAGE LES RENCONTRES FRANCE-BRÉSIL, DU MARACANÃ, L’HISTOIRE THIAGO SILVA, NEYMAR, DANIEL ALVES, DAVID LUIZ LUIZ DAVID ALVES, DANIEL NEYMAR, SILVA, THIAGO ACTEURS, MUSICIENS, JOURNALISTES, POLITIQUES : ILS DONNENT LEURS AVIS SUR LE MONDIAL AVIS : ILS DONNENT LEURS POLITIQUES MUSICIENS, JOURNALISTES, ACTEURS, Belgique/Luxembourg : 3.50 €/Maroc : 40 Mad/Dom surface : 4.00 €/Tom 440 CFP/Zone CFA : 2500 cfa 2500 : CFA CFP/Zone 440 €/Tom 4.00 : surface Mad/Dom 40 : €/Maroc 3.50 : Belgique/Luxembourg COUVERTURE TEXTE : TONY DAVID, MARCELO MARTINS, ALEXANDRE PAUL DÉMÉTRIUS ET RÉMI DUMONT - PHOTOS : VIVIEN LAVAU NEYMAR, THIAGO SILVA, DANIEL ALVES ET DAVID LUIZ succès, c’est aussi à cause d’une tant que l’on ne le pense. D’après gestion à tâtons de sa sélection. David Luiz, « cela nous a ren- Depuis le dernier Mondial, pas dus plus confiants, plus forts. moins de cent joueurs ont été Maintenant, nous sommes plus utilisés par trois sélection- respectés à travers le monde, neurs différents (Dunga, Mano car les gens ont vu que nous for- Menezes et Luiz Felipe Scolari) mions une bonne équipe. -

Juventus Falls to Barcellona in Champions League Published on Iitaly.Org (

Juventus Falls to Barcellona in Champions League Published on iItaly.org (http://www.iitaly.org) Juventus Falls to Barcellona in Champions League Alessandro Antonio Pugliese (June 06, 2015) In Berlin. Both teams were champions of their respective leagues and their domestic cups, so the winner of this match would complete the Treble, which is when a team wins three trophies in a single season. The last time an Italian team made it to the Champions League Final, Inter won the Treble in 2010. Barcelona and Juventus squared off in the UEFA Champions League Final at the Olympiastadion i The atmosphere in Berlin was fantastic and it also was in New York City. On 6 West 33rd Street at the Football Factory at Legends Pub NYC, a large crowd of Juventus fans arrived hours before kickoff, most dressed in the traditional black-and-white jerseys of La Vecchia Signora. Juventus Club NYC member Mara Gerety said “Confidence is high . this is going to be one amazing game of football.” Many thought it would be a walk in the park for Barcelona and after scoring in the 4th minute it looked like it might be just that. But Barça had to battle hard until the very end. The Spanish champions completed 15 passes in the build up to the first goal as the Brazilian Neymar played a ball to Andres Inestia who sprinted into the box and then played a square pass to Ivan Rakitic, who scored with a tap in. It was a brilliant start for the Blaugrana and it looked like a blowout could have been in the cards. -

THUMBNAILS Cristiano Ronaldo Has Felt Relaxed After Joining Juventus

Cristiano Ronaldo has felt relaxed after joining Juventus. RADOMIR ANTIC FORMER COACH OF REAL MADRID, BARCELONA AND ATLETICO MADRID BHUBANESWAR, THURSDAY 21 FEBRUARY 2019 11 THUMBNAILS Ryder Cup: Steve Stricker will be named the captain When Barcelona drew blank of the US 2020 Ryder Cup team, according to multi- We played good football, but you have to hit the target as well, and we didn't: Valverde ple reports, becoming the first American in the role AGENCE FRANCE-PRESSE The visitors -- who started crowd of almost 58,000 with a a little bit of a disappointment, last 16 tie at Anfield. without a major title. LYON, 20 FEBRUARY: with Sergi Roberto in midfield thunderous strike from 20 yards but there is still the second leg Sadio Mane wasted the best Stricker would become rather than the out-of-form out in the ninth minute that was to come and we hope to do bet- chance for the hosts on Tues- the 29th US captain and arcelona coach Ernesto Philippe Coutinho -- had good tipped onto the bar by Marc- ter,” said defender Clement day, when the Senegalese for- be charged with reclaim- Valverde (in photo) reason to be wary of their hosts, Andre ter Stegen. The same play- Lenglet. At least they extend- ward fired wide during an open ing the trophy. shrugged off his team's who have excelled in big games er later shot over at the end of ed their unbeaten record against first 45 minutes, but a cagey sec- Bstruggles in front of this season. Bruno Genesio's a fantastic move, while Houssem Lyon to seven matches, but ond half left it all to be decid- goal after they were held to a team had taken four points Aouar had earlier been denied there remains hope for the ed when the sides meet again 0-0 draw away at Lyon in the from a possible six against by the goalkeeper, but it was French club ahead of the return. -

Data-Driven Performance Evaluation and Player Ranking in Soccer Via a Machine Learning Approach

PlayeRank: data-driven performance evaluation and player ranking in soccer via a machine learning approach Luca Pappalardo∗ Paolo Cintia† Paolo Ferragina Institute of Information Science and Department of Computer Science, Department of Computer Science, Techologies (ISTI), CNR University of Pisa University of Pisa Pisa, Italy Pisa, Italy Pisa, Italy [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Emanuele Massucco Dino Pedreschi Fosca Giannotti Wyscout Department of Computer Science, Institute of Information Science and Chiavari, Italy University of Pisa Techologies (ISTI), CNR [email protected] Pisa, Italy Pisa, Italy [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT 1 INTRODUCTION The problem of evaluating the performance of soccer players is Rankings of soccer players and data-driven evaluations of their attracting the interest of many companies and the scientific com- performance are becoming more and more central in the soccer munity, thanks to the availability of massive data capturing all the industry [5, 12, 28, 33]. On the one hand, many sports companies, events generated during a match (e.g., tackles, passes, shots, etc.). websites and television broadcasters, such as Opta, WhoScored.com Unfortunately, there is no consolidated and widely accepted metric and Sky, as well as the plethora of online platforms for fantasy for measuring performance quality in all of its facets. In this paper, football and e-sports, widely use soccer statistics to compare the we design and implement PlayeRank, a data-driven framework that performance of professional players, with the purpose of increasing offers a principled multi-dimensional and role-aware evaluation of fan engagement via critical analyses, insights and scoring patterns. -

MP-ES — Ministério Público Do Estado Do Espírito Santo

MP-ES — Ministério Público do Estado do Espírito Santo Eder Pontes da Silva Procuradores de Justiça: Procurador-Geral de Justiça José Adalberto Dazzi José Maria Rodrigues de Oliveira Eloiza Helena Chiabai Filho Elda Marcia Moraes Spedo Sérgio Dário Machado Fernando Franklin da Costa Santos Sócrates de Souza Subprocuradora-Geral de Justiça Administrativo Catarina Cecin Gazele Valdeci de Lourdes P. Vasconcelos Licéa Maria de Moraes Carvalho Josemar Moreira José Marçal de Ataíde Assi Carla Viana Cola Elcy de Souza Subprocurador-Geral de Justiça Judicial Heloisa Malta Carpi Ivanilce da Cruz Romão Fernando Zardini Antonio Fábio Vello Corrêa Célia Lúcia Vaz de Araújo Alexandre José Guimarães José Claudio Rodrigues Pimenta Subprocurador-Geral de Justiça Institucional Antonio Carlos Amancio Pereira Mariela Santos Neves Siqueira Andréa Maria da Silva Rocha Maria da Penha de Mattos Saudino Domingos Ramos Ferreira Adonias Zam Maria Elizabeth de Moraes Corregedora-Geral do Ministério Público Eliezer Siqueira de Sousa Elias Faissal Junior Amâncio Pereira Gabriel de Souza Cardoso Maria Auxiliadora Freire Machado Ouvidor do Ministério Público Rua : Procurador Antônio Benedicto Amancio Pereira, 121, Santa Helena - 29050-265 - Vitória/ES — www.mpes.gov.br Data: (Sexta-feira) 07 de junho de 2013. PROCURADORIA GERAL DE JUSTIÇA ATO DO SENHOR PROCURADOR-GERAL DE JUSTIÇA: O PROCURADOR-GERAL DE JUSTIÇA, no uso de suas atribuições legais, assinou os seguintes atos: Convênio MP/nº 008/2013. Celebrado entre o Ministério Público do Estado do Espírito Santo e o Município de São Mateus. - Resumo - Objeto: Regulamentar a cessão e disponibilidade de Servidores do Município de São Mateus, durante o prazo de vigência do presente instrumento.