First Documented Record of Common Swift Apus Apus for Surinam and South America Marijke N

Total Page:16

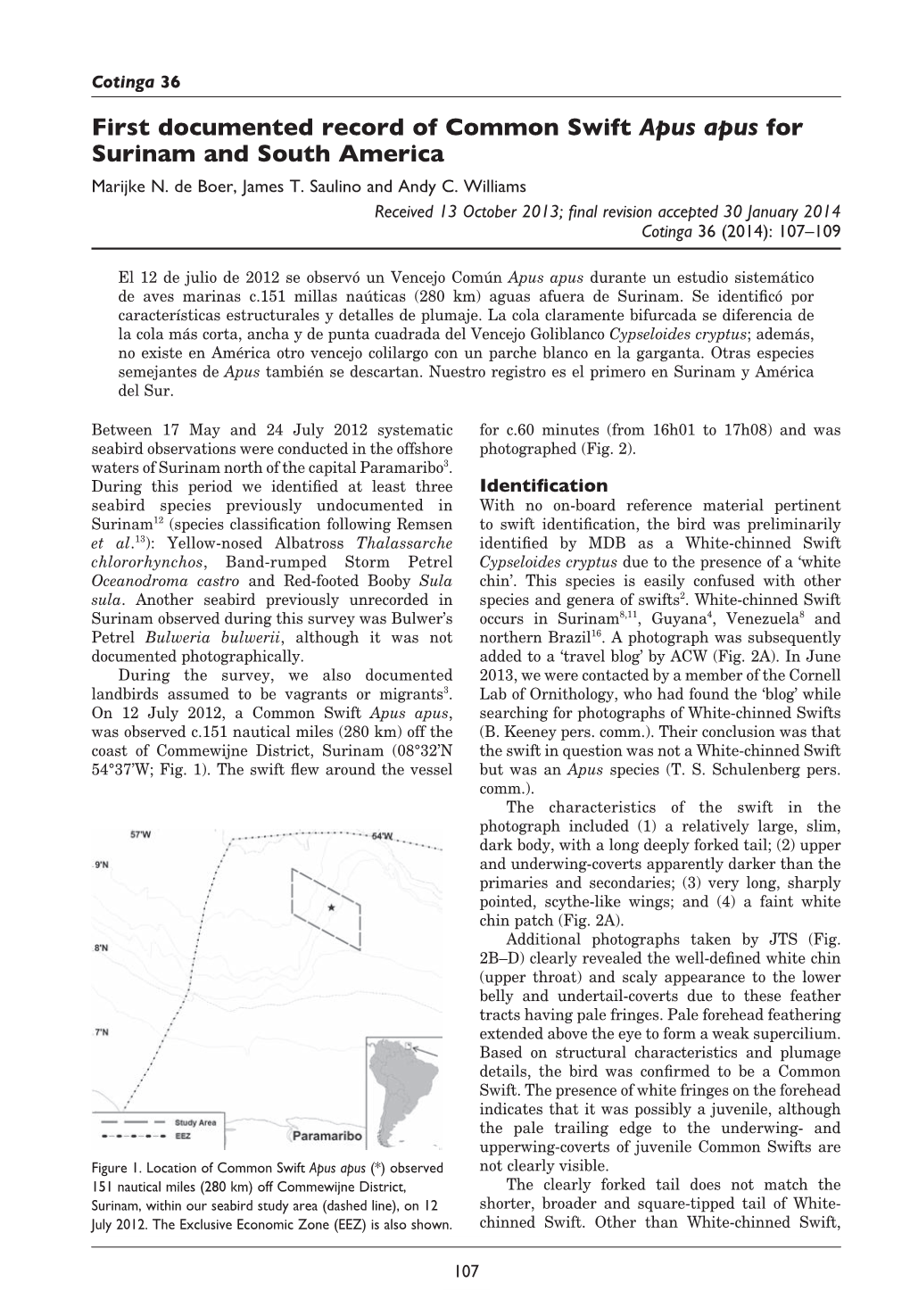

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cali Types of the Common Swift Apus Apus: Aduit Cali Given at the Nest

Avocetta W 17: 141-146 (1993) Cali types of the Common Swift Apus apus: aduIt cali given at the nest VrNCENT BRETAGNOLLE CEBC-CNRS,F-79360-Beauvoirsur Niort, France Abstract - Vocalizations of the Common Swifts were studi ed during two consecutive springs in southern France. I found that three cali types were given by the adults at the nest, and these are described quantitatively. Significant differences in the acoustic parameters of the calls are highlighted, as well as. a probable sexual dimorphism. This, together with the precise signification of the different cali types, rernam however to be critically assessed by playback experiments. Introduction France), where a large colony is easily accessible for field studies (for further details, see Gory, this Swifts (Order Apodiformes) are unusual among birds volume).A sample of 22 accessible nests was because many of their Iife history traits (i.e. longevity, selected, for which extensive data on breeding biology delayed maturity, large egg size) make them atypical and breeding success were also available dating from compared to similar-sized birds (Lack 1956, Gaillard 1978 (Gory et Jeantet 1986). The birds were tape et al. 1989), and convergent evolution of life histories recorded by Uher 4400 or Nagra IV at a speed of 19.5 with, e.g., long lived seabirds such as cmJs, on Agfa PE43 tapes, and with a Seinnheiser Procellariiformes, have been suggested repeatedly omnidirectional microphone MD421 placed within, or (e.g. Lack and Lack 1951, Malacarne et al. 1991). at the entrance of, the nesting cavity. Calls were Although investigations have been carried out on the analysed on a Real Time Spectrograph, which Common Swift Apus apus with regard to demography performs a fast Fourier transform (Richard 1991) at a (Lack 1956, Perrins 1971, Lebreton et al. -

Notes on the Breeding Biology of the White-Throated Swift in Southern California

Bull. Southern California Acad. Sci. 109(2), 2010, pp. 23–36 E Southern California Academy of Sciences, 2010 Notes on the Breeding Biology of the White-Throated Swift in Southern California Charles T. Collins Department of Biological Sciences, California State University, Long Beach, CA 90840, [email protected] Abstract.—Reproductive activities of White-throated Swifts (Aeronautes saxatalis) were examined from 1997 to 2006 at two nest sites in a human-made structure in southern California. The start of egg-laying was from 27 April to 30 May and hatching of the first chick ranged from 21 May to 23 June; all chicks had fledged by late July, 42–43 days after hatching. The annual molt of adults began in early June and broadly overlapped with the chick-rearing period. Year to year adult survival was minimally 73.9% and nesting pairs showed strong mate and nest site fidelity; pairs reused nests up to five consecutive years. The composition of the arthropod food (insects and spiders) brought to nestlings was different in the periods 1997–2000 and 2001–2004 but prey size was similar in both periods. The onset of breeding was more varied from year to year than the start of the primary feather molt suggesting differing environmental stimuli for these important components of the annual cycle. The White-throated Swift (Aeronautes saxatalis) is a widespread and familiar element of the southern California avifauna. Its staccato chattering vocalization often announces its presence, searching for aerial prey high overhead, long before visual contact is made. In recent decades, this swift has utilized human-made structures as buildings, bridges and highway overpasses for nesting and roosting (Collins and Johnson 1982; Ryan and Collins 2000). -

View Preprint

Does evolution of plumage patterns and of migratory behaviour in Apodini swifts (Aves: Apodiformes) follow distributional range shifts? Dieter Thomas Tietze, Martin Päckert, Michael Wink The Apodini swifts in the Old World serve as an example for a recent radiation on an intercontinental scale on the one hand. On the other hand they provide a model for the interplay of trait and distributional range evolution with speciation, extinction and trait s t transition rates on a low taxonomic level (23 extant taxa). Swifts are well adapted to a life n i mostly in the air and to long-distance movements. Their overall colouration is dull, but r P lighter feather patches of chin and rump stand out as visual signals. Only few Apodini taxa e r breed outside the tropics; they are the only species in the study group that migrate long P distances to wintering grounds in the tropics and subtropics. We reconstructed a dated molecular phylogeny including all species, numerous outgroups and fossil constraints. Several methods were used for historical biogeography and two models for the study of trait evolution. We finally correlated trait expression with geographic status. The differentiation of the Apodini took place in less than 9 Ma. Their ancestral range most likely comprised large parts of the Old-World tropics, although the majority of extant taxa breed in the Afrotropic and the closest relatives occur in the Indomalayan. The expression of all three investigated traits increased speciation rates and the traits were more likely lost than gained. Chin patches are found in almost all species, so that no association with phylogeny or range could be found. -

Notas Breves FOOD HABITS of the ALPINE SWIFT on TWO

Ardeola 56(2), 2009, 259-269 Notas Breves FOOD HABITS OF THE ALPINE SWIFT ON TWO CONTINENTS: INTRA- AND INTERSPECIFIC COMPARISONS DIETA DEL VENCEJO REAL EN DOS CONTINENTES: ANÁLISIS COMPARATIVO INTRA E INTERESPECÍFICO Charles T. COLLINS* 1, José L. TELLA** and Brian D. COLAHAN*** SUMMARY.—The prey brought by alpine swifts Tachymarptis melba to their chicks in Switzerland, Spain and South Africa included a wide variety of arthropods, principally insects but also spiders. Insects com- prised 10 orders and 79 families, the Homoptera, Diptera and Hymenoptera being the most often con- sumed. The assessment of geographical variation in the diet was complicated by the great variability among the individual supplies of prey. Prey size varied between 1.3 and 29.6 mm, differing significantly in the median prey size of the three populations (5.12 - 8.81 mm) according to the intraspecific variation in size of alpine swifts. In an interspecific comparison, prey size correlated positively with body size in seven species of swifts. RESUMEN.—Las presas aportadas por vencejos reales Tachymarptis melba a sus pollos en Suiza, Es- paña y Sudáfrica incluyeron una amplia variedad de artrópodos, principalmente insectos pero también arañas. Entre los insectos, fueron identificados 10 órdenes y 79 familias, siendo Homoptera, Diptera e Hymenoptera los más consumidos. Las variaciones geográficas en la dieta se vieron ensombrecidas por una gran variabilidad entre los aportes individuales de presas. El tamaño de presa varió entre 1.3 y 29.6 mm, oscilando las medianas para cada población entre 5,12 y 8,81 mm. Los vencejos reales mostraron di- ferencias significativas en el tamaño de sus presas correspondiendo con su variación intraespecífica en tamaño. -

"Official Gazette of RM", No. 28/04 and 37/07), the Government of the Republic of Montenegro, at Its Meeting Held on ______2007, Enacted This

In accordance with Article 6 paragraph 3 of the FT Law ("Official Gazette of RM", No. 28/04 and 37/07), the Government of the Republic of Montenegro, at its meeting held on ____________ 2007, enacted this DECISION ON CONTROL LIST FOR EXPORT, IMPORT AND TRANSIT OF GOODS Article 1 The goods that are being exported, imported and goods in transit procedure, shall be classified into the forms of export, import and transit, specifically: free export, import and transit and export, import and transit based on a license. The goods referred to in paragraph 1 of this Article were identified in the Control List for Export, Import and Transit of Goods that has been printed together with this Decision and constitutes an integral part hereof (Exhibit 1). Article 2 In the Control List, the goods for which export, import and transit is based on a license, were designated by the abbreviation: “D”, and automatic license were designated by abbreviation “AD”. The goods for which export, import and transit is based on a license designated by the abbreviation “D” and specific number, license is issued by following state authorities: - D1: the goods for which export, import and transit is based on a license issued by the state authority competent for protection of human health - D2: the goods for which export, import and transit is based on a license issued by the state authority competent for animal and plant health protection, if goods are imported, exported or in transit for veterinary or phyto-sanitary purposes - D3: the goods for which export, import and transit is based on a license issued by the state authority competent for environment protection - D4: the goods for which export, import and transit is based on a license issued by the state authority competent for culture. -

Tinamiformes – Falconiformes

LIST OF THE 2,008 BIRD SPECIES (WITH SCIENTIFIC AND ENGLISH NAMES) KNOWN FROM THE A.O.U. CHECK-LIST AREA. Notes: "(A)" = accidental/casualin A.O.U. area; "(H)" -- recordedin A.O.U. area only from Hawaii; "(I)" = introducedinto A.O.U. area; "(N)" = has not bred in A.O.U. area but occursregularly as nonbreedingvisitor; "?" precedingname = extinct. TINAMIFORMES TINAMIDAE Tinamus major Great Tinamou. Nothocercusbonapartei Highland Tinamou. Crypturellus soui Little Tinamou. Crypturelluscinnamomeus Thicket Tinamou. Crypturellusboucardi Slaty-breastedTinamou. Crypturellus kerriae Choco Tinamou. GAVIIFORMES GAVIIDAE Gavia stellata Red-throated Loon. Gavia arctica Arctic Loon. Gavia pacifica Pacific Loon. Gavia immer Common Loon. Gavia adamsii Yellow-billed Loon. PODICIPEDIFORMES PODICIPEDIDAE Tachybaptusdominicus Least Grebe. Podilymbuspodiceps Pied-billed Grebe. ?Podilymbusgigas Atitlan Grebe. Podicepsauritus Horned Grebe. Podicepsgrisegena Red-neckedGrebe. Podicepsnigricollis Eared Grebe. Aechmophorusoccidentalis Western Grebe. Aechmophorusclarkii Clark's Grebe. PROCELLARIIFORMES DIOMEDEIDAE Thalassarchechlororhynchos Yellow-nosed Albatross. (A) Thalassarchecauta Shy Albatross.(A) Thalassarchemelanophris Black-browed Albatross. (A) Phoebetriapalpebrata Light-mantled Albatross. (A) Diomedea exulans WanderingAlbatross. (A) Phoebastriaimmutabilis Laysan Albatross. Phoebastrianigripes Black-lootedAlbatross. Phoebastriaalbatrus Short-tailedAlbatross. (N) PROCELLARIIDAE Fulmarus glacialis Northern Fulmar. Pterodroma neglecta KermadecPetrel. (A) Pterodroma -

Diet of Breeding White-Throated and Black Swifts in Southern California

DIET OF BREEDING WHITE-THROATED AND BLACK SWIFTS IN SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA ALLISON D. RUDALEVIGE, DESSlE L. A. UNDERWOOD, and CHARLES T. COLLINS, Department of BiologicalSciences, California State University,Long Beach, California 90840 (current addressof Rudalevige:Biology Department, Universityof California,Riverside, California 92521) ABSTRACT: We analyzed the diet of nestling White-throated(Aeronautes saxatalis) and Black Swifts (Cypseloidesniger) in southern California. White- throatedSwifts fed their nestlingson bolusesof insectsmore taxonomicallydiverse, on average(over 50 arthropodfamilies represented), than did BlackSwifts (seven arthropodfamilies, primarfiy ants). In some casesWhite-throated Swift boluses containedprimarily one species,while other bolusesshowed more variation.In contrast,all BlackSwift samplescontained high numbersof wingedants with few individualsof other taxa. Our resultsprovide new informationon the White-throated Swift'sdiet and supportprevious studies of the BlackSwift. Swiftsare amongthe mostaerial of birds,spending most of the day on the wing in searchof their arthropodprey. Food itemsinclude a wide array of insectsand some ballooningspiders, all gatheredaloft in the air column (Lack and Owen 1955). The food habitsof a numberof speciesof swifts have been recorded(Collins 1968, Hespenheide1975, Lack and Owen 1955, Marfn 1999, Tarburton 1986, 1993), but there is stilllittle informa- tion availablefor others, even for some speciesthat are widespreadand common.Here we providedata on the prey sizeand compositionof food broughtto nestlingsof the White-throated(Aerona u tes saxa talis) and Black (Cypseloidesniger) Swifts in southernCalifornia. The White-throatedSwift is a commonresident that nestswidely in southernCalifornia, while the Black Swift is a local summerresident, migrating south in late August (Garrettand Dunn 1981, Foersterand Collins 1990). METHODS When feedingyoung, swifts of the subfamiliesApodinae and Chaeturinae return to the nest with a bolusof food in their mouths(Collins 1998). -

Fastest Migration Highest

GO!” Everyone knows birds can fly. ET’S But not everyone knows that “L certain birds are really, really good at it. Meet a few of these champions of the skies. Flying Acby Ellen eLambeth; art sby Dave Clegg! Highest You don’t have to be a lightweight to fly high. Just look at a Ruppell’s griffon vulture (left). One was recorded flying at an altitude of 36,000 feet. That’s as high as passenger planes fly! In fact, it’s so high that you would pass out from lack of oxygen if you weren’t inside a plane. How does the vulture manage? It has Fastest (on the level) Swifts are birds that have that name for good special blood cells that make a small amount reason: They’re speedy! The swiftest bird using its own of oxygen go a long way. flapping-wing power is the common swift of Europe, Asia, and Africa (below). It’s been clocked at nearly 70 miles per hour. That’s the speed limit for cars on some highways. Vroom-vroom! Fastest (in a dive) Fastest Migration With gravity helping out, a bird can pick up extra speed. Imagine taking a trip of about 4,200 And no bird can go faster than a peregrine falcon in a dive miles. Sure, you could easily do it in an airplane. after prey (right). In fact, no other animal on Earth can go as But a great snipe (right) did it on the wing in just fast as a peregrine: more than 200 miles per hour! three and a half days! That means it averaged about 60 miles The prey, by the way, is usually another bird, per hour during its migration between northern which the peregrine strikes in mid-air with its balled-up Europe and central Africa. -

Peru: from the Cusco Andes to the Manu

The critically endangered Royal Cinclodes - our bird-of-the-trip (all photos taken on this tour by Pete Morris) PERU: FROM THE CUSCO ANDES TO THE MANU 26 JULY – 12 AUGUST 2017 LEADERS: PETE MORRIS and GUNNAR ENGBLOM This brand new itinerary really was a tour of two halves! For the frst half of the tour we really were up on the roof of the world, exploring the Andes that surround Cusco up to altitudes in excess of 4000m. Cold clear air and fantastic snow-clad peaks were the order of the day here as we went about our task of seeking out a number of scarce, localized and seldom-seen endemics. For the second half of the tour we plunged down off of the mountains and took the long snaking Manu Road, right down to the Amazon basin. Here we traded the mountainous peaks for vistas of forest that stretched as far as the eye could see in one of the planet’s most diverse regions. Here, the temperatures rose in line with our ever growing list of sightings! In all, we amassed a grand total of 537 species of birds, including 36 which provided audio encounters only! As we all know though, it’s not necessarily the shear number of species that counts, but more the quality, and we found many high quality species. New species for the Birdquest life list included Apurimac Spinetail, Vilcabamba Thistletail, Am- pay (still to be described) and Vilcabamba Tapaculos and Apurimac Brushfnch, whilst other montane goodies included the stunning Bearded Mountaineer, White-tufted Sunbeam the critically endangered Royal Cinclodes, 1 BirdQuest Tour Report: Peru: From the Cusco Andes to The Manu 2017 www.birdquest-tours.com These wonderful Blue-headed Macaws were a brilliant highlight near to Atalaya. -

Bird) Species List

Aves (Bird) Species List Higher Classification1 Kingdom: Animalia, Phyllum: Chordata, Class: Reptilia, Diapsida, Archosauria, Aves Order (O:) and Family (F:) English Name2 Scientific Name3 O: Tinamiformes (Tinamous) F: Tinamidae (Tinamous) Great Tinamou Tinamus major Highland Tinamou Nothocercus bonapartei O: Galliformes (Turkeys, Pheasants & Quail) F: Cracidae Black Guan Chamaepetes unicolor (Chachalacas, Guans & Curassows) Gray-headed Chachalaca Ortalis cinereiceps F: Odontophoridae (New World Quail) Black-breasted Wood-quail Odontophorus leucolaemus Buffy-crowned Wood-Partridge Dendrortyx leucophrys Marbled Wood-Quail Odontophorus gujanensis Spotted Wood-Quail Odontophorus guttatus O: Suliformes (Cormorants) F: Fregatidae (Frigatebirds) Magnificent Frigatebird Fregata magnificens O: Pelecaniformes (Pelicans, Tropicbirds & Allies) F: Ardeidae (Herons, Egrets & Bitterns) Cattle Egret Bubulcus ibis O: Charadriiformes (Sandpipers & Allies) F: Scolopacidae (Sandpipers) Spotted Sandpiper Actitis macularius O: Gruiformes (Cranes & Allies) F: Rallidae (Rails) Gray-Cowled Wood-Rail Aramides cajaneus O: Accipitriformes (Diurnal Birds of Prey) F: Cathartidae (Vultures & Condors) Black Vulture Coragyps atratus Turkey Vulture Cathartes aura F: Pandionidae (Osprey) Osprey Pandion haliaetus F: Accipitridae (Hawks, Eagles & Kites) Barred Hawk Morphnarchus princeps Broad-winged Hawk Buteo platypterus Double-toothed Kite Harpagus bidentatus Gray-headed Kite Leptodon cayanensis Northern Harrier Circus cyaneus Ornate Hawk-Eagle Spizaetus ornatus Red-tailed -

Crustacea, Notostraca) from Iran

Journal of Biological Research -Thessaloniki 19 : 75 – 79 , 20 13 J. Biol. Res. -Thessalon. is available online at http://www.jbr.gr Indexed in: Wos (Web of science, IsI thomson), sCOPUs, CAs (Chemical Abstracts service) and dOAj (directory of Open Access journals) — Short CommuniCation — on the occurrence of Lepidurus apus (Linnaeus, 1758) (Crustacea, notostraca) from iran Behroz AtAshBAr 1,2 *, N aser Agh 2, L ynda BeLAdjAL 1 and johan MerteNs 1 1 Department of Biology , Faculty of Science , Ghent University , K.L. Ledeganckstraat 35 , 9000 Gent , Belgium 2 Department of Biology and Aquaculture , Artemia and Aquatic Animals Research Institute , Urmia University , Urmia-57153 , Iran received: 16 November 2011 Accepted after revision: 18 july 2012 the occurrence of Lepidurus apus in Iran is reported for the first time. this species was found in Aigher goli located in the mountains area, east Azerbaijan province (North east, Iran). details on biogeography, ecology and morphology of this species are provided. Key words: Lepidurus apus , Aigher goli, east Azerbaijan, Iran. INtrOdUCtION their world-wide distribution is due to their anti qu - ity, but possibly also to their passive transport: geo - Notostracan records date back to the Carboniferous graphical barriers are more effective for non-passive - and possibly up to the devonian period (Wallossek, ly distributed animals. From an ecological point of 1993, 1995; Kelber, 1998). In fact, there are Upper view, notostracans, like most branchiopods, are re - triassic Triops fossils from germany -

Lista Das Aves Do Brasil

90 Annotated checklist of the birds of Brazil by the Brazilian Ornithological Records Committee / Lista comentada das aves do Brasil pelo Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos content / conteÚDO Abstract ............................. 91 Charadriiformes ......................121 Scleruridae .............187 Charadriidae .........121 Dendrocolaptidae ...188 Introduction ........................ 92 Haematopodidae ...121 Xenopidae .............. 195 Methods ................................ 92 Recurvirostridae ....122 Furnariidae ............. 195 Burhinidae ............122 Tyrannides .......................203 Results ................................... 94 Chionidae .............122 Pipridae ..................203 Scolopacidae .........122 Oxyruncidae ..........206 Discussion ............................. 94 Thinocoridae .........124 Onychorhynchidae 206 Checklist of birds of Brazil 96 Jacanidae ...............124 Tityridae ................207 Rheiformes .............................. 96 Rostratulidae .........124 Cotingidae .............209 Tinamiformes .......................... 96 Glareolidae ............124 Pipritidae ............... 211 Anseriformes ........................... 98 Stercorariidae ........125 Platyrinchidae......... 211 Anhimidae ............ 98 Laridae ..................125 Tachurisidae ...........212 Anatidae ................ 98 Sternidae ...............126 Rhynchocyclidae ....212 Galliformes ..............................100 Rynchopidae .........127 Tyrannidae ............. 218 Cracidae ................100 Columbiformes