On Our Doorsteps 2010-12: Summary Report and Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Moulsecoomb & Bevendean

Moulsecoomb & Bevendean Neighbourhood Action Plan(NAP) Stanmer S Coldean Brighton Aldridge Community A27 Academy St Georges’s Community East Centre Moulsecoomb North Moulsecoomb The Orchards Moulsecoomb Community Room Leisure Centre Moulsecoomb Way Moulsecoomb S Birdham Road Hillview Good News Centre Children’s Moulsecoomb Centre Primary Moulsecoomb Boxing Club 67 Centre Moulsecoomb Moulsecoomb Library Hall Jubilee Court St Andrew’s Community Room Church Drive & Hall Holy Nativity Norwich C Church & Community Centre Hollingdean GP C Bevendean Ave Real Junk The Avenue Food Project Scout Hut S The Avenue & Community Garden University GP Bevendean of Brighton Cockcroft Heath HillPrimary Bevendean Lewes Road A270 S Coomb Road Primary Bear Road Moulsecoomb Brighton Aldridge & Bevendean Community Academy Neighbourhood Community Woodingdean Map Stanmer & Hollingdean Moulsecoomb Woodingdean Hillview Good News Centre Moulsecoomb Health Centre & Bevendean Moulsecoomb Boxing Club 67 Centre Stanford Norwich Hanover East Brighton Real Junk Food Project The Bevy Community S = School Pub C = Church GP = GP Surgery = Railway & Moulsecoomb Bevendean Hill View, Moulsecoomb The Moulsecoomb & Bevendean Neighbourhood Action Plan is based on local knowledge and Moulsecoomb Hall experiences that identifies priorities, resources and opportunities for people living in Moulsecoomb & Bevendean. The Bevy, community pub in Bevendean 4 w & Moulsecoomb Bevendean Bevendean primary Moulsecoomb primary Moulsecoomb Leisure Centre Moulsecoomb Library Holy Nativity community centre 5 Moulsecoomb & Bevendean Welcome to the (NAP) Neighbourhood Action Plan When communities work with each This NAP aims to fulfil the other and with local services, there commitment within the Brighton are more opportunities to listen, & Hove Collaboration Framework understand each other and shape working collaboratively to improve services that work. -

Route 70 Lower Bevendean

Route 70 Lower Bevendean - East Moulsecoomb Adult Single Fares citySAVER networkSAVER The Avenue/Lewes Rd Discovery 190 Lower Bevendean loop Metrobus Metrovoyager 270 190 The Avenue 270 190 190 East Moulsecoomb Accepted throughout. Please see the fares menu on this website for details. PlusBus Route 71 Whitehawk - Hove Park - Mile Oak Brighton PlusBus tickets accepted throughout. Please see Mile Oak Loop www.plusbus.info for further information. 190 Hove Park School 270 190 Boundary Road Concessionary Passes 270 270 190 Tesco/Hove St If you are a Brighton and Hove resident CentreFare area 270 270 270 190 Hove Town Hall You cannot travel free in the city area on Mondays to Fridays 270 270 270 270 190 Palmeira Square between 0400 and 0900 270 270 270 270 220 190 Churchill Square If you start your journey outside the city (eg. Lewes) you 270 270 270 270 220 220 190 North St/Old Steine/St James’s Street cannot have free travel until 0930 270 270 270 270 220 220 220 190 Upper Bedford Street 270 270 270 270 220 220 220 220 190 Roedean Rd/Lidl Any other resident 270 270 270 270 270 270 270 270 270 190 Swanborough Drive You cannot travel free between 2300 and 0930 on Mondays to Route 72 Whitehawk - Woodingdean Fridays Whitehawk, All Stops There are no time restrictions for any passes at weekends and 270 Downland Road on Bank Holidays (valid from 0001 until midnight). 270 190 Downs Hotel 270 270 190 Cowley Drive 270 270 270 190 Longhill School Fares are shown in pence. -

How Will You #PUSHBACK?

HE CAMPAIGN AND EXHIBITION, which is part Your City HOUSING RUNNING CRIPPLING of this year’s Brighton Fringe Festival, was Your say… IS A HUMAN FLAT OUT TO PAY MONTHLY Join BHCLT today RIGHT YOUR RENT? PAYMENT? inspired by the award-winning documentary #PUSHBACKBRIGHTON #PUSHBACKBRIGHTON #PUSHBACKBRIGHTON #PUSHBACKBRIGHTON film, PUSH. The film follows Leilani Farha, the TUN’s special rapporteur on adequate housing, as she Site 21a travels the world investigating why ordinary people C can’t afford to live in cities anymore. O END L D One of the key players in this worrying trend is E A Blackstone, a global financer buying up affordable N housing around the world. What is even more shocking L A N E is that Blackstone already own some of the more 3: COLDEAN Walking time: 25 mins unaffordable student housing in Brighton, after buying Distance: 1.2 miles – mostly flat iQ student housing firm in the UK’s largest ever private with steeper off road footpath up START property deal recently. to Site 21a Follow the trails to hunt the boards and find out more Start: Middleton Rise End: Site 21a (behind Varley Halls) about how initiatives like community led housing can WITHDEAN PARK Visit coldeancommunity.org help us all #PUSHBACK against local land grabs and or use the QR code on right to unaffordable and unsustainable development. As find out about their trail. communities and individuals deal with the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic, the need for secure and affordable housing is more important than ever. As BHCLT’s ‘Housing and Lockdown’ survey showed, there is a profound link between people’s housing situation and D PRESTON MOULSECOOMB Y their wellbeing; with 60% of renters in particular, saying K PARK their housing situation made lockdown harder. -

25 Tivoli & Prestonvilleneighbourhood

25 tivoli & prestonvilleneighbourhood context key stages of historic development Tivoli and Prestonville neighbourhood lies on average 2km from the city centre on the M23 to London A27 Dyke Road sustainable transport corridor. Dyke Road hollingbury M23 to London to Lewes/ Tivoli asda 1865 Eastbourne The neighbourhood lies to the north of Seven Dials, an important city hub, and along copse 15 mins by bus A27 the eastern side of the Dyke Road ridge. In the 19th century the area was home to Falmer station market gardens, windmills, brick fields and a large open air laundry. The land on both sides of Old Shoreham Road (the original Prestonville) began development as A27 Moulsecoomb Preston to Southampton a middle-class housing estate in the mid 1860s. In the 1880s the Port Hall area was station developed in the north of the neighbourhood. The network of streets to the west, which village Preston Park were named after English towns and cities, were added in the 1890s. Development The Drove station to southampton continued northward along and to the east of Dyke Road reaching the area around London Road Tivoli Crescent North and Preston Park Station by 1920. Millers Tivoli & Prestonville station moulsecoomb stn Road neighbourhood railway preston park stn lewes rd The south of the neighbourhood contains some high quality mid-19th century buildings whilst Dyke Road hosts among others the remnants of Port Hall, the Booth Museum sainsburys windmill Hovebrighton station station 7 mins by bus of Natural History and the Church of the Good Shepherd. bus via london rd london road stn central Hove railway hove stn typology Port Hall Brighton station london rd 7 minutes by bus shops Tivoli and Prestonville neighbourhood may be classified as Shoreham 5 mins by bus an urban pre-1914 residential inner suburb whose street Road city centre further 3 pattern, architecture and character have been well preserved. -

100 Years of Council Housing in Brighton and Hove 1919

100 Years of Council Housing in Brighton & Hove 1919 - 2019 By Alan Cooke and Di Parkin Brighton & Hove University of the Third Age Local History Group Social Housing in Brighton before 1919 Brighton (and to a lesser extent Hove) had long been an area with a large number of poor people who could not afford decent housing. In 1795 – The Percy Almshouses were built for six widows, in Lewes Road, by the Level and Elm Grove In 1859 – the Wagner Almshouses were added to the Percy building Reports by Edward Cresy in 1848 and Dr Wm Kebbell in 1849 (Inspectors for the General Board of Health) painted sombre portraits of life in Brighton’s slums, and Kebbell set up a charitable trust to build ‘Model Dwellings For the Poor’ in Church Street and Clarence Yard in the early 1860s. The Percy and Wagner Almshouses, 1795 and 1859 Kebbell’s Model Dwellings in Church Street and Clarence Yard, 1860s The Revd Arthur Wagner and others Between 1870 and 1895, it is estimated that the Revd Arthur Wagner, Vicar of St Paul’s Church, spent around £40,000 building houses for the poorer people of Brighton. That is equivalent to about £3.5 mn today. Most of these houses were along the lower slopes and streets of what is now Hanover, and also between Lewes Road and Upper Lewes Road, where his churches of The Annunciation and St Martins now stand. The ‘working classes’ were heavily dependent upon philanthropists such as Wagner and others to provide decent accommodation at affordable prices. Slum clearances Brighton had long been notorious for its slums, particularly in the Pimlico and Carlton Hill areas. -

70 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

70 bus time schedule & line map 70 Lower Bevendean - Moulsecoomb (Brighton View In Website Mode Academy) The 70 bus line Lower Bevendean - Moulsecoomb (Brighton Academy) has one route. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Moulsecoomb: 7:38 AM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 70 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 70 bus arriving. Direction: Moulsecoomb 70 bus Time Schedule 33 stops Moulsecoomb Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 7:38 AM Brighton University, Moulsecoomb Tuesday 7:38 AM The Avenue Steps, Moulsecoomb The Avenue Steps, Brighton and Hove Wednesday 7:38 AM Manton Road, Bevendean Thursday 7:38 AM Friday 7:38 AM The Avenue Shops, Bevendean Saturday Not Operational Hazelgrove, Bevendean Surgery, Bevendean School, Bevendean 70 bus Info Direction: Moulsecoomb Knepp Close, Bevendean Stops: 33 Trip Duration: 26 min Line Summary: Brighton University, Moulsecoomb, Norwich Crescent, Bevendean The Avenue Steps, Moulsecoomb, Manton Road, Bevendean, The Avenue Shops, Bevendean, Kenilworth Close, Bevendean Hazelgrove, Bevendean, Surgery, Bevendean, School, Norwich Drive, Brighton and Hove Bevendean, Knepp Close, Bevendean, Norwich Crescent, Bevendean, Kenilworth Close, Bevendean, Norwich Close, Bevendean Norwich Close, Bevendean, Norwich Drive East End, Norwich Close, Brighton and Hove Bevendean, Bodiam Close, Bevendean, Bodiam Avenue, Bevendean, Hornby Road, Bevendean, Norwich Drive East End, Bevendean Leybourne Road, Bevendean, Leybourne Parade, Bevendean, Taunton Way, Bevendean, -

Support for Groups in East Brighton Trust Area 2017

Support for groups in East Brighton Trust area 2017 In 2017 the Resource Centre supported 23 different community groups in East Brighton with funding from East Brighton Trust (EBT). These are all grassroots community groups which are run by and for the local community. One-to-one support Accounts examinations We carried out 22 consultancy sessions with 15 different We carried out Examinations of Accounts for 16 different EBT groups. All of our support aims to help groups find a EBT groups. solution to issues they are grappling with, and are We carry out a thorough examination of the groups’ therefore tailor-made for the group. financial records and produce a detailed, clear and easy to Our consultancy sessions have covered the following understand balance sheet for their members, funders and areas: the Charity Commission (where applicable). • Book keeping advice If groups are having any difficulties we offer further • Budgeting advice and support. • Setting up an accounts system • Producing newsletters Feedback from groups • Legal structures and governance We received feedback cards from 50% of these groups. • Getting a group started 7 said the service was excellent and 1 said it was good. • Fundraising applications and strategy Our feedback from Tuesday Lunch Club, on their post • Writing letters examination support session provides a good insight into • Working in a committee how this process works: • Planning and event “The support was very helpful - more than I expected • Surveys and questionnaires because the trainer took me through each stage of what In addition to planned meetings we provide ‘quick is quite a complex process. -

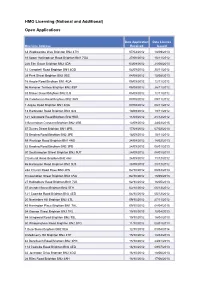

HMO Licensing (National and Additional) Open Applications

HMO Licensing (National and Additional) Open Applications Date Application Date Licence One Line Address Received Issued 63 Widdicombe Way Brighton BN2 4TH 07/03/2012 18/09/2013 16 Upper Hollingdean Road Brighton BN1 7GA 27/06/2012 15/11/2012 226 Elm Grove Brighton BN2 3DA 03/09/2012 21/06/2013 12 Campbell Road Brighton BN1 4QD 04/09/2012 30/11/2012 26 Park Street Brighton BN2 0BS 04/09/2012 15/08/2013 16 Argyle Road Brighton BN1 4QA 05/09/2012 12/11/2012 96 Hanover Terrace Brighton BN2 9SP 05/09/2012 26/11/2012 33 Blaker Street Brighton BN2 0JJ 05/09/2012 12/11/2012 39 Caledonian Road Brighton BN2 3HX 07/09/2012 09/11/2012 1 Argyle Road Brighton BN1 4QA 07/09/2012 08/11/2012 18 Hartington Road Brighton BN2 3LS 10/09/2012 19/11/2012 121 Islingword Road Brighton BN2 9SG 11/09/2012 21/12/2012 3 Bevendean Crescent Brighton BN2 4RB 12/09/2012 24/03/2015 57 Surrey Street Brighton BN1 3PB 17/09/2012 07/02/2013 75 Brading Road Brighton BN2 3PE 18/09/2012 15/11/2012 69 Warleigh Road Brighton BN1 4NS 24/09/2012 18/02/2013 62 Brading Road Brighton BN2 3PD 24/09/2012 08/01/2013 30 Southampton Street Brighton BN2 9UT 24/09/2012 08/01/2013 2 Ewhurst Road Brighton BN2 4AJ 24/09/2012 11/12/2012 46 Hartington Road Brighton BN2 3LS 28/09/2012 21/12/2012 28A Church Road Hove BN3 2FN 02/10/2012 08/02/2013 9 Coronation Street Brighton BN2 3AQ 02/10/2012 15/05/2013 27 Hollingbury Road Brighton BN1 7JB 02/10/2012 16/05/2013 37 Arundel Street Brighton BN2 5TH 02/10/2012 05/12/2012 121 Coombe Road Brighton BN2 4ED 04/10/2012 05/12/2012 20 Nyetimber Hill Brighton -

Moulsecoomb Station I Onward Travel Information Buses Local Area Map

Moulsecoomb Station i Onward Travel Information Buses Local area map Rail replacement buses depart down from the station at existing bus stops on A27 Lewes Road. Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2020 & also map data © OpenStreetMap contributors, CC BY-SA Main destinations by bus (Data correct at July 2020) DESTINATION BUS ROUTES BUS STOP DESTINATION BUS ROUTES BUS STOP DESTINATION BUS ROUTES BUS STOP Amex Community Stadium Eridge Green/ Royal Sussex County 25, N25 A 28, 29 A 23 B (Falmer) ^ Eridge Station Hospital 24, 25, 28, South Whitehawk Halland 28** A 23 B Brighton (City Centre) # 29, 48, 49, B (Roedean Road) N25 Stanmer Park/ 23, 24, 25, Hollingbury (Asda) 24 A Brighton Stanmer Village 23, 25, N25 A 28, 29, 48, B (Lewes Road/Elm Grove) Hove (University Slip Road) 49, N25 25*, 49 B Sussex University (George Street Shops) 28, 29, 29B* A Brighton (A27 Bus Stop) ^ 24, 48, 49 B Isfield (London Road Shops) 29, 29B* A (Lavender Line Station) 24, 25, 28, Sussex University (Falmer) 23, 25, N25 A Kemp Town (Buzz Bingo Brighton (Old Steine) 29, 48, 49, B 23 B N25 Eastern Road) Tunbridge Wells 28, 29, 29X* A 24, 25, 28, 28, 29, 29B*, Lewes ^ A 28, 29, 29B*, Brighton (St Peter's Church) 29, 48, 49, B 29X* Uckfield A 29X* N25 Lower Bevendean 48 C (Bodiam Avenue) Brighton Marina 23 B 23, 24, 25, North Moulsecoomb Brighton University 28, 29, 29B*, A Notes 25, N25 A (Lewes Road/Coldean Lane) (Falmer) 29X*, N25 Bus routes 23, 24, 25, 28, 29, 48 and 49 operate daily. -

Moulsecoomb: Being Heard!

Moulsecoomb: Being Heard! REPORT by Moulsecoomb: Being Heard! Project Group: Armstrong, M Moulsecoomb resident *Conyers, D Institute of Development Studies, University of Sussex Cook, J Moulsecoomb resident Davies, C Scarman Trust Funnell, M Moulescoomb resident Jones, H Moulsescoomb resident *MacDonald, D Health and Social Policy Research Centre, University of Brighton Stevenson, C Moulsecoomb resident Tighe-Ford, S East Brighton New Deal for Communities Toner, M Moulsecoomb resident Webb, G Moulsecoomb resident * Report authors April 2008 ii FOREWORD This is a contribution to our series of research papers which brings work in the Health and Social Policy Research Centre (HSPRC) and the School of Applied Social Science to a wider audience. The HSPRC aims to: foster and sustain quality research in health and social policy contribute to knowledge, theoretical development and debate inform policy making, teaching and practice Its main areas of expertise are in: community and service user empowerment inter-agency working and partnership needs analysis and evaluation health and social policy policing and criminal justice psycho social studies HSPRC publishes a regular newsletter and an Annual Report, as well as a separate series of occasional papers. Recent reports include: Chandler, T. and Cresdee, S. (2008) The Revolving Door research Project Brighton and Hove 2008: “Climbing Everest Naked” Stone, J. (2008) An evaluation of volunteer opportunities offered by the Brighton Unemployed Centre Family Project Banks, L. (2007) Evaluation of „Safe + Sorted‟ Youth Centre MacDonald, D. (2007) Evaluation of the Brighton and Hove ASpire Project Further information about the Centre can be obtained from: Sallie White, Research Administrator, HSPRC University of Brighton, Falmer, Brighton, BN1 9PH Telephone: 01273 643480 Fax: 01273 643496 Email: [email protected] iii iv Acknowledgements The members of the Moulsecoomb: Being Heard! Project Group would like to express their thanks to all those who contributed to the research. -

The Aim of This Report Is to Describe What We Know About the Population of Disabled Children and Young People in Brighton and Hove

The Population of Disabled Children and Young People in Brighton and Hove The aim of this report is to describe what we know about the population of disabled children and young people in Brighton and Hove. We look at the distribution of children across the city, child deprivation and child disability. We have analysed data from: • the Compass • the Indices of Deprivation (ID 2007) and • the numbers of children receiving Disability Living Allowance (DLA). Until recently the smallest geographical areas at which data, such as Census and ID data, was published was ward level. Different wards can vary widely in area (and population) and most are too large to be useful for pinpointing small areas of deprivation (see below). Brighton and Hove ward map 1 Brunswick and Adelaide 2 Central Hove 3 East Brighton 4 Goldsmid 5 Hangleton and Knoll 6 Hanover and Elm Grove 14 Rottingdean Coastal 7 Hollingbury and Stanmer 15 St Peters and North Laine 8 Moulsecoomb and Bevendean 16 South Portslade 9 North Portslade 17 Stanford 10 Patcham 18 Westbourne 11 Preston Park 19 Wish 12 Queens Park 20 Withdean 13 Regency 21 Woodingdean 1 Super output areas (SOAs) are new geographical reporting units that have been introduced to help overcome these limitations. They are designed to have similar numbers of residents (an average of 1,500 and a minimum of 1,000), so that more meaningful comparisons between different areas can be made. They are constrained by ward boundaries, so data can be aggregated to provide ward level information. These “lower layer” SOAs have also been combined into larger units, known as “middle layer” SOAs (MSOAs). -

Coldean Neighbourhood May Be Classified As Suburban Downland Fringe with a 20Th Century Residential Suburb That Was Deliberately Planned

4 coldeanneighbourhood context key stages of historic development Coldean is a mainly post-WW2 suburb lying in a deep valley between Hollingbury and Stanmer and located off one of the main sustainable transport corridors, the Stanmer House 1897 Hollingbury Lewes Road. A23 to London Asda A27 5 mins by bus Prior to its development there were a few cottages and farm buildings near Lewes Great Wood to Lewes/ Eastbourne Road and along the track later to become Coldean Lane. These included the Coldean late 18th century flint barn of Coldean Farm also known as the Menagerie. This neighbourhood building partly survives as St Mary Magdalene’s Church and community centre. Falmer station The first housing development started in 1934 at the southern end of the to Southampton neighbourhood and was completed in 1948. The main council housing development took place in the post-WW2 era providing a mix of properties, Moulsecoomb station mainly family homes. The most recent major development has been the detached the Menagerie Preston Park student campus accommodation at Varley Halls for Brighton University. station Lewes Road London sainsburys Coldean Wood Road 16 mins by bus Brighton station typology station Coldean neighbourhood may be classified as suburban downland fringe with a 20th century residential suburb that was deliberately planned. Low rise, low Hove station density semi-detached and terraced housing much of which was built as public Moulsecoomb Pit London Road housing. Poor access to local services but strong identity. shops railway 20 mins by bus Refer to the introduction and summary for more information on landscape character types.