Moulsecoomb: Being Heard!

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Moulsecoomb & Bevendean

Moulsecoomb & Bevendean Neighbourhood Action Plan(NAP) Stanmer S Coldean Brighton Aldridge Community A27 Academy St Georges’s Community East Centre Moulsecoomb North Moulsecoomb The Orchards Moulsecoomb Community Room Leisure Centre Moulsecoomb Way Moulsecoomb S Birdham Road Hillview Good News Centre Children’s Moulsecoomb Centre Primary Moulsecoomb Boxing Club 67 Centre Moulsecoomb Moulsecoomb Library Hall Jubilee Court St Andrew’s Community Room Church Drive & Hall Holy Nativity Norwich C Church & Community Centre Hollingdean GP C Bevendean Ave Real Junk The Avenue Food Project Scout Hut S The Avenue & Community Garden University GP Bevendean of Brighton Cockcroft Heath HillPrimary Bevendean Lewes Road A270 S Coomb Road Primary Bear Road Moulsecoomb Brighton Aldridge & Bevendean Community Academy Neighbourhood Community Woodingdean Map Stanmer & Hollingdean Moulsecoomb Woodingdean Hillview Good News Centre Moulsecoomb Health Centre & Bevendean Moulsecoomb Boxing Club 67 Centre Stanford Norwich Hanover East Brighton Real Junk Food Project The Bevy Community S = School Pub C = Church GP = GP Surgery = Railway & Moulsecoomb Bevendean Hill View, Moulsecoomb The Moulsecoomb & Bevendean Neighbourhood Action Plan is based on local knowledge and Moulsecoomb Hall experiences that identifies priorities, resources and opportunities for people living in Moulsecoomb & Bevendean. The Bevy, community pub in Bevendean 4 w & Moulsecoomb Bevendean Bevendean primary Moulsecoomb primary Moulsecoomb Leisure Centre Moulsecoomb Library Holy Nativity community centre 5 Moulsecoomb & Bevendean Welcome to the (NAP) Neighbourhood Action Plan When communities work with each This NAP aims to fulfil the other and with local services, there commitment within the Brighton are more opportunities to listen, & Hove Collaboration Framework understand each other and shape working collaboratively to improve services that work. -

Route 21 Brighton Marina

Route 21 Brighton Marina - Whitehawk - Queens Park - City Centre -Hove - Goldstone Valley Emergency timetable from Monday 18 May and every Monday to Saturday until further notice. For Sunday and Bank Holiday times see separate pdf. route 21 21 21 21A 21A 21A 21A 21A 21A 21A 21A 21A 21 21 21 21 Brighton Marina 0711 0811 0911 1011 1111 1211 1311 1411 1511 1611 1711 1811 1919 2019 2119 Whitehawk Garage 0610 0714 0814 0914 1014 1114 1214 1314 1414 1514 1614 1714 1814 1922 2022 2122 Stanley Deason Leisure Centre 0612 0716 0816 0916 1016 1116 1216 1316 1416 1516 1616 1716 1816 - - - Swanborough Drive 0614 0718 0818 0919 1019 1119 1219 1319 1419 1519 1619 1719 1819 - - - Whitehawk Crescent 0621 0725 0825 0926 1026 1126 1226 1326 1426 1526 1626 1726 1825 1924 2024 2124 St Lukes Church 0626 0730 0830 0931 1031 1131 1231 1331 1431 1531 1631 1731 1830 1928 2028 2128 Bottom of Elm Grove 0631 0735 0835 0936 1036 1136 1236 1336 1436 1536 1636 1736 1835 1932 2032 2132 London Rd Shops (S) 0634 0739 0839 0940 1040 1140 1240 1340 1440 1540 1640 1740 1839 1935 2035 2135 Old Steine (H) 0639 0744 0844 0945 1045 1145 1245 1345 1445 1545 1645 1745 1844 1939 2039 2139 Brighton Stn (D) 0644 0749 - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Churchill Sq (B) 0647 0752 0849 0950 1050 1150 1250 1350 1450 1550 1650 1750 1849 1942 2042 2142 Palmeira Square 0652 0757 0854 - - - - - - - - - 1858 Furze Croft - - - 0955 1056 1156 1256 1356 1456 1556 1656 1756 - Hove Cricket Ground - - - 0957 1058 1158 1258 1358 1458 1558 1658 1758 - Hove Town Hall (B) 0655 0800 0857 1000 1101 1201 1301 1401 1501 1601 1701 1800 1859 Hove Station 0658 0803 0900 1003 1104 1204 1304 1404 1504 1604 1704 1803 1900 Goldstone Valley Shops 0707 0812 0909 1012 1114 1214 1314 1414 1514 1614 1714 1813 1909 Route 21 Goldstone Valley -Hove - City Centre - Queens Park - Whitehawk - Brighton Marina Emergency timetable from Monday 18 May and every Monday to Saturday until further notice. -

Route 70 Lower Bevendean

Route 70 Lower Bevendean - East Moulsecoomb Adult Single Fares citySAVER networkSAVER The Avenue/Lewes Rd Discovery 190 Lower Bevendean loop Metrobus Metrovoyager 270 190 The Avenue 270 190 190 East Moulsecoomb Accepted throughout. Please see the fares menu on this website for details. PlusBus Route 71 Whitehawk - Hove Park - Mile Oak Brighton PlusBus tickets accepted throughout. Please see Mile Oak Loop www.plusbus.info for further information. 190 Hove Park School 270 190 Boundary Road Concessionary Passes 270 270 190 Tesco/Hove St If you are a Brighton and Hove resident CentreFare area 270 270 270 190 Hove Town Hall You cannot travel free in the city area on Mondays to Fridays 270 270 270 270 190 Palmeira Square between 0400 and 0900 270 270 270 270 220 190 Churchill Square If you start your journey outside the city (eg. Lewes) you 270 270 270 270 220 220 190 North St/Old Steine/St James’s Street cannot have free travel until 0930 270 270 270 270 220 220 220 190 Upper Bedford Street 270 270 270 270 220 220 220 220 190 Roedean Rd/Lidl Any other resident 270 270 270 270 270 270 270 270 270 190 Swanborough Drive You cannot travel free between 2300 and 0930 on Mondays to Route 72 Whitehawk - Woodingdean Fridays Whitehawk, All Stops There are no time restrictions for any passes at weekends and 270 Downland Road on Bank Holidays (valid from 0001 until midnight). 270 190 Downs Hotel 270 270 190 Cowley Drive 270 270 270 190 Longhill School Fares are shown in pence. -

Changes to Bus Services in Brighton and Hove the Following Changes to Bus Services Will Take Place in January 2018

Changes to Bus Services in Brighton and Hove The following changes to bus services will take place in January 2018 Service No. Route details Changes to current service Service provided Date of by change 1 Whitehawk - County The combined service 1/1A evening frequency will be improved - from Brighton & Hove 14.01.18 Hospital - City Centre - every 15 minutes to every 12 minutes - for most of the evening on Buses Hove - Portslade – Valley Mondays to Saturdays. There will be an additional morning commuter Road - Mile Oak journey on service 1 from Whitehawk to Mile Oak, Monday to Friday - plus an additional journey at 7.29am from Hove Town Hall to Mile Oak on schooldays. 1A Whitehawk - County Please see service 1, above. Brighton & Hove 14.01.18 Hospital - City Centre - Buses Hove - Portslade – Mile Oak Road - Mile Oak N1 (night Whitehawk - County Night Bus N1 will be revised to operate westbound only, from Brighton Brighton & Hove 14.01.18 bus) Hospital - City Centre - Station, then via Churchill Square and the current N1 route to Mile Oak Buses Hove - Portslade - Mile and Downs Park. There will be no eastbound journeys. Oak - Downs Park The section of route from Churchill Square to Whitehawk will be withdrawn. Service N7 provides an alternative between the city centre and Kemp Town (Roedean Road/Arundel Road). On Monday to Saturday nights, the revised N1 will leave Brighton Station at 12.40am, then every 30 minutes until 3.10am, then 4.10am. On Sunday nights buses leave Brighton Station at 12.40am, 1.40am and 2.40am. -

Gas Works Marina Jan 2012.Qxp

Gas Works Marina Key facts Total area: 2Ha Page 1 of 2 Location: Adjacent to Brighton Seafront overlooking Brighton Marina Ownership: The north east of the site is owned by Southern Gas Networks (Scotia). The remainder is owned by National Grid Property Holdings Ltd The Site Access The former Gas Works site is adjacent to the The A259 serves the site. It is a primary route A259 coastal road and in the vicinity of Black into the city and as well as a major distributor Rock (itself offering redevelopment road running east-west along the seafront and opportunities), Brighton Marina District Shopping linking Brighton and Hove with the port of centre and East Brighton Park. Residential uses Newhaven to the East and Shoreham to the surround much of the site and immediately to West. It is a sustainable transport corridor and the North West there are a number of small bus priority route. The primary site entrance is industrial units at Bell Tower Industrial Estate. from Boundary Road, with a secondary access The site itself is predominately given over to point from Marina Way. temporary uses such as storage, parking and light industrial uses. Two gasometers remain on Redevelopment opportunities land owned by Southern Gas Networks in the The site is allocated for residential and northeast corner of the site, although these are employment uses in the Local Plan. The not in constant use. continued potential for both housing and employment is also recognised in the most recent housing assessment and employment study. With its proximity to Black Rock and Brighton Marina, there are also opportunities for a broader and more comprehensive redevelopment that could unlock the potential of all three sites to the benefit of the various landowners, local communities and the city as a whole. -

Ice Age Brighton Ice Age

All about Ice Age Brighton Ice Age What do you think of when you hear the phrase ‘Ice Age’? Make a list with your partner. Ice Age? People call it an ice Why do age because thick people call it sheets of ice, called the Ice Age? glaciers, cover lots of the earth’s surface. We are still technically in the Ice Age now, but are in an ‘interglacial’ period, meaning temperatures are slightly higher. So just how long ago are we talking? 5,000 years 2.5 million ago? to 11,000 1,000 years years ago? ago? It’s safe to say that’s quite a long time ago then! Ice Age Bronze Age Roman Black Rock Hove Barrow Springfield Road 220,000 years ago 3,500 years ago 2,000 years ago Neolithic Iron Age Anglo Saxon Whitehawk Hollingbury Stafford Road 5,700 years ago 2,800 years ago 1,400 years ago Here’s how the Ice Age fits into our local timeline – it’s the oldest period we will look at. How does this period fit into worldwide prehistory? Use of fibres First to produce Invention pyramids Ice Age Iron Age First Black Rock clothing of wheel built Hollingbury Writing 220,000 years ago 35,000 years ago 5,500 years ago 4,700 years ago 2,800 years ago 2,000 years ago First Homo Neolithic Hieroglyphic Bronze Age Romans Anglo sapiens Whitehawk Hove Barrow Springfield Road 5,700 years ago script 3,500 years ago 2,000 years ago Saxons Africa Stafford Road 200,000 years ago developed 1,400 years ago 5,100 years ago Find out about the Ice Age 1. -

73 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

73 bus time schedule & line map 73 Cardinal Newman School - Whitehawk View In Website Mode The 73 bus line (Cardinal Newman School - Whitehawk) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Hove: 7:38 AM (2) Whitehawk: 3:15 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 73 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 73 bus arriving. Direction: Hove 73 bus Time Schedule 30 stops Hove Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday Not Operational Swanborough Drive, Whitehawk Tuesday Not Operational Haybourne Road, Whitehawk Wednesday Not Operational Coolham Drive, Whitehawk Thursday 7:38 AM Pulborough Close, Brighton and Hove Friday Not Operational St Cuthmans Church, Whitehawk Whitehawk Way, Brighton and Hove Saturday Not Operational Piltdown Road, Whitehawk Community Hub, Whitehawk Selmeston Place, Brighton and Hove 73 bus Info Direction: Hove St David's Hall, Whitehawk Stops: 30 Hellingly Close, Brighton and Hove Trip Duration: 32 min Line Summary: Swanborough Drive, Whitehawk, Findon Road, Whitehawk Haybourne Road, Whitehawk, Coolham Drive, Whitehawk, St Cuthmans Church, Whitehawk, Bus Garage, Whitehawk Piltdown Road, Whitehawk, Community Hub, Whitehawk, St David's Hall, Whitehawk, Findon Road, Arundel Road, Brighton Whitehawk, Bus Garage, Whitehawk, Arundel Road, Brighton, Lidl Superstore, Brighton, Sussex Square, Lidl Superstore, Brighton Kemp Town, St Mary's Hall, Kemp Town, Chesham Street, Kemp Town, County Hospital, Kemp Town, Arundel Road, Brighton and Hove College Place, Kemp Town, Upper -

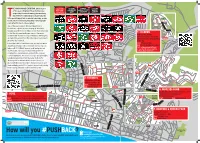

How Will You #PUSHBACK?

HE CAMPAIGN AND EXHIBITION, which is part Your City HOUSING RUNNING CRIPPLING of this year’s Brighton Fringe Festival, was Your say… IS A HUMAN FLAT OUT TO PAY MONTHLY Join BHCLT today RIGHT YOUR RENT? PAYMENT? inspired by the award-winning documentary #PUSHBACKBRIGHTON #PUSHBACKBRIGHTON #PUSHBACKBRIGHTON #PUSHBACKBRIGHTON film, PUSH. The film follows Leilani Farha, the TUN’s special rapporteur on adequate housing, as she Site 21a travels the world investigating why ordinary people C can’t afford to live in cities anymore. O END L D One of the key players in this worrying trend is E A Blackstone, a global financer buying up affordable N housing around the world. What is even more shocking L A N E is that Blackstone already own some of the more 3: COLDEAN Walking time: 25 mins unaffordable student housing in Brighton, after buying Distance: 1.2 miles – mostly flat iQ student housing firm in the UK’s largest ever private with steeper off road footpath up START property deal recently. to Site 21a Follow the trails to hunt the boards and find out more Start: Middleton Rise End: Site 21a (behind Varley Halls) about how initiatives like community led housing can WITHDEAN PARK Visit coldeancommunity.org help us all #PUSHBACK against local land grabs and or use the QR code on right to unaffordable and unsustainable development. As find out about their trail. communities and individuals deal with the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic, the need for secure and affordable housing is more important than ever. As BHCLT’s ‘Housing and Lockdown’ survey showed, there is a profound link between people’s housing situation and D PRESTON MOULSECOOMB Y their wellbeing; with 60% of renters in particular, saying K PARK their housing situation made lockdown harder. -

25 Tivoli & Prestonvilleneighbourhood

25 tivoli & prestonvilleneighbourhood context key stages of historic development Tivoli and Prestonville neighbourhood lies on average 2km from the city centre on the M23 to London A27 Dyke Road sustainable transport corridor. Dyke Road hollingbury M23 to London to Lewes/ Tivoli asda 1865 Eastbourne The neighbourhood lies to the north of Seven Dials, an important city hub, and along copse 15 mins by bus A27 the eastern side of the Dyke Road ridge. In the 19th century the area was home to Falmer station market gardens, windmills, brick fields and a large open air laundry. The land on both sides of Old Shoreham Road (the original Prestonville) began development as A27 Moulsecoomb Preston to Southampton a middle-class housing estate in the mid 1860s. In the 1880s the Port Hall area was station developed in the north of the neighbourhood. The network of streets to the west, which village Preston Park were named after English towns and cities, were added in the 1890s. Development The Drove station to southampton continued northward along and to the east of Dyke Road reaching the area around London Road Tivoli Crescent North and Preston Park Station by 1920. Millers Tivoli & Prestonville station moulsecoomb stn Road neighbourhood railway preston park stn lewes rd The south of the neighbourhood contains some high quality mid-19th century buildings whilst Dyke Road hosts among others the remnants of Port Hall, the Booth Museum sainsburys windmill Hovebrighton station station 7 mins by bus of Natural History and the Church of the Good Shepherd. bus via london rd london road stn central Hove railway hove stn typology Port Hall Brighton station london rd 7 minutes by bus shops Tivoli and Prestonville neighbourhood may be classified as Shoreham 5 mins by bus an urban pre-1914 residential inner suburb whose street Road city centre further 3 pattern, architecture and character have been well preserved. -

Food Banks in Brighton & Hove East West

Food Banks in Brighton & Hove East Bevendean Food Bank - Church Hall, Norwich Drive, BN2 4LA. Open Wednesday 9:00-12:00 (10:00 over summer). Drop in with proof of postcode for people in Lower and Higher Bevendean, Moulsecoomb, Bates Estate, Saunders Park, Meadow View and Lewes Road corridor. The Cafe is also open from 9:00 - 12:00 every Wednesday with advisors on hand to give free advice on debts, benefits and housing. Contact: 07449 464695 or email [email protected] Whitehawk Foodbank - St Cuthman's Church, Whitehawk Way, BN2 5HE. Open Wednesday 12:00-14:00. Referral only. Contact: 07941397648 or [email protected] Roundabout Children's Centre - Whitehawk Road, BN2 5FL. Open Thursday morning from 9:00. Referral only through Children's Centre/health visitors, for local families with children under 5. Contact: 01273 290300 or [email protected] / [email protected] The Vale Community Centre food bank - 17a Hadlow Close, BN2 0FH. Open Friday 12:30 - 13:30. Drop-in with proof of postcode; BN2 0F, BN2 0E, BN2 9D, BN2 9Y, BN2 9Z. Contact: 01273 571573 or [email protected] West Salvation Army Foodbank - 159 Sackville Road, Hove, BN3 3HD. Open Friday 10:00-14:00. Referrals via phone, email and people can self-refer by turning up, ideally on Friday. Appointments can be arranged for other days preferably through a referral agency. Contact: 01273 323072/07954614838 or [email protected] Hangleton and West Blatchington Food Bank - St George's Church Hall, 13 Court Farm, Hove, BN3 7QR. -

71A Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

71A bus time schedule & line map 71A Portslade Academy - Hangleton - Hove - Brighton View In Website Mode The 71A bus line Portslade Academy - Hangleton - Hove - Brighton has one route. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Mile Oak: 7:16 AM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 71A bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 71A bus arriving. Direction: Mile Oak 71A bus Time Schedule 53 stops Mile Oak Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 7:16 AM Swanborough Drive, Whitehawk Tuesday 7:16 AM Haybourne Road, Whitehawk Wednesday 7:16 AM Coolham Drive, Whitehawk Thursday 7:16 AM Pulborough Close, Brighton and Hove Friday 7:16 AM St Cuthmans Church, Whitehawk Whitehawk Way, Brighton and Hove Saturday Not Operational Piltdown Road, Whitehawk Community Hub, Whitehawk Selmeston Place, Brighton and Hove 71A bus Info Direction: Mile Oak St David's Hall, Whitehawk Stops: 53 Hellingly Close, Brighton and Hove Trip Duration: 58 min Line Summary: Swanborough Drive, Whitehawk, Findon Road, Whitehawk Haybourne Road, Whitehawk, Coolham Drive, Whitehawk, St Cuthmans Church, Whitehawk, Bus Garage, Whitehawk Piltdown Road, Whitehawk, Community Hub, Whitehawk, St David's Hall, Whitehawk, Findon Road, Arundel Road, Brighton Whitehawk, Bus Garage, Whitehawk, Arundel Road, Brighton, Lidl Superstore, Brighton, Sussex Square, Lidl Superstore, Brighton Kemp Town, St Mary's Hall, Kemp Town, Chesham Street, Kemp Town, County Hospital, Kemp Town, Arundel Road, Brighton and Hove College Place, Kemp Town, Upper Bedford -

100 Years of Council Housing in Brighton and Hove 1919

100 Years of Council Housing in Brighton & Hove 1919 - 2019 By Alan Cooke and Di Parkin Brighton & Hove University of the Third Age Local History Group Social Housing in Brighton before 1919 Brighton (and to a lesser extent Hove) had long been an area with a large number of poor people who could not afford decent housing. In 1795 – The Percy Almshouses were built for six widows, in Lewes Road, by the Level and Elm Grove In 1859 – the Wagner Almshouses were added to the Percy building Reports by Edward Cresy in 1848 and Dr Wm Kebbell in 1849 (Inspectors for the General Board of Health) painted sombre portraits of life in Brighton’s slums, and Kebbell set up a charitable trust to build ‘Model Dwellings For the Poor’ in Church Street and Clarence Yard in the early 1860s. The Percy and Wagner Almshouses, 1795 and 1859 Kebbell’s Model Dwellings in Church Street and Clarence Yard, 1860s The Revd Arthur Wagner and others Between 1870 and 1895, it is estimated that the Revd Arthur Wagner, Vicar of St Paul’s Church, spent around £40,000 building houses for the poorer people of Brighton. That is equivalent to about £3.5 mn today. Most of these houses were along the lower slopes and streets of what is now Hanover, and also between Lewes Road and Upper Lewes Road, where his churches of The Annunciation and St Martins now stand. The ‘working classes’ were heavily dependent upon philanthropists such as Wagner and others to provide decent accommodation at affordable prices. Slum clearances Brighton had long been notorious for its slums, particularly in the Pimlico and Carlton Hill areas.