MOVIE DIARY Teaching Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Comics, Graphic Novels, Manga, & Anime

SAN DIEGO PUBLIC LIBRARY PATHFINDER Comics, Graphic Novels, Manga, & Anime The Central Library has a large collection of comics, the Usual Extra Rarities, 1935–36 (2005) by George graphic novels, manga, anime, and related movies. The Herriman. 741.5973/HERRIMAN materials listed below are just a small selection of these items, many of which are also available at one or more Lions and Tigers and Crocs, Oh My!: A Pearls before of the 35 branch libraries. Swine Treasury (2006) by Stephan Pastis. GN 741.5973/PASTIS Catalog You can locate books and other items by searching the The War Within: One Step at a Time: A Doonesbury library catalog (www.sandiegolibrary.org) on your Book (2006) by G. B. Trudeau. 741.5973/TRUDEAU home computer or a library computer. Here are a few subject headings that you can search for to find Graphic Novels: additional relevant materials: Alan Moore: Wild Worlds (2007) by Alan Moore. cartoons and comics GN FIC/MOORE comic books, strips, etc. graphic novels Alice in Sunderland (2007) by Bryan Talbot. graphic novels—Japan GN FIC/TALBOT To locate materials by a specific author, use the last The Black Diamond Detective Agency: Containing name followed by the first name (for example, Eisner, Mayhem, Mystery, Romance, Mine Shafts, Bullets, Will) and select “author” from the drop-down list. To Framed as a Graphic Narrative (2007) by Eddie limit your search to a specific type of item, such as DVD, Campbell. GN FIC/CAMPBELL click on the Advanced Catalog Search link and then select from the Type drop-down list. -

JEFF KINNEY: Might Act Them Out, Or Even Create Scenarios for the TELLING FUNNY STORIES Different Types of Laughter

SPONSORED BY IN PARTNERSHIP WITH AGES 9-11 NOTES FOR TEACHERS & LIBRARIANS type of laugh that they list – or, better still, they JEFF KINNEY: might act them out, or even create scenarios for the TELLING FUNNY STORIES different types of laughter. Ask students to share their different types of laughter with their classmates. Are they ready to snigger, giggle or snort when they watch Jeff’s video? AFTER WATCHING THE VIDEO AND READING THE EXTRACT: DISCUSSION QUESTIONS 1. Do you think the series title Diary of a Wimpy Kid is a funny title? Why? 2. What is effective about using the form of adiary to document Greg’s adventures? Do you like this format? Why? How does it change the experience BEFORE WATCHING THE VIDEO AND of reading? READING THE EXTRACT: 3. Jeff Kinney often uses words made up of capital GET IN THE ZONE! letters in his writing. Can you find any examples of this in the extract? What is the effect of using The Diary of a Wimpy Kid series by Jeff Kinney capital letters? What do they show? is well-known for its humour and ability to make people laugh. 4. Can you find an example ofonomatopoeia in the extract? Why is this an effective technique for A good way to get students in the right frame creating comedy? of mind for telling funny stories is to get them thinking about laughter. Ask them to consider the 5. How does Jeff Kinney present the relationship following questions in pairs: What is laughter? between Greg and his parents in the extract from When do we laugh? Why is it important? When Diary of a Wimpy Kid: The Meltdown? Why is was the last time you really laughed? this funny? Then, ask students to list as many types of laughs 6. -

Diary-Of-A-Wimpy-Kid-Double-Down-1

OTHER BOOKS BY JEFF KINNEY Diary of a Wimpy Kid Diary of a Wimpy Kid: Rodrick Rules Diary of a Wimpy Kid: The Last Straw Diary of a Wimpy Kid: Dog Days Diary of a Wimpy Kid: The Ugly Truth Diary of a Wimpy Kid: Cabin Fever Diary of a Wimpy Kid: The Third Wheel Diary of a Wimpy Kid: Hard Luck Diary of a Wimpy Kid: The Long Haul Diary of a Wimpy Kid: Old School The Wimpy Kid Do-It-Yourself Book The Wimpy Kid Movie Diary --, COMING SOON: MORE DIARY OFA WIMPY KID 131ARY- by Jeff Kihhey TO DORIAN _ - - - _ OCTOBER Vlextbies4c7 revolve drouhci rne, bu+ some+irnes dcAuttlIp0.0ES. V6ebliarsksckia:de-kkL---T-sdw----+-6snovie cti.ciu+ d meth w6se wl)ole life is secre+ly 1)6113 filmed for d TV show. l'his world, ahri 1)e_gloe 1-11+ KNOW i+. 14e11÷ -Yrn_sihce_ Saw ovie,,Tve k;hj of 3 +0 MF. HOPE YOU- CREEPS ARE ENJOYING YOURSELVES. eYery day +0 see wl)a+±a3__±_6d-!._s._Lithgdiy____ kihcl of COOL. +0 De i+s _awh +elev;sioh S~owr so sone4iiiI3stheri+tvihib3 ever_haw_dhcLibei_v_e Auskte- 2 si3hdls +o le+ -14)er..) khow rn ih oh 4e sure+. , Bete' cornmercia_lreaks.W&ANesicis_ wIleh Im ih Ale bd+Ilroorn, dke a b;3 eh+r-dhce. cif+er 1 fihisillere_. 3 131/±saple±iniesl_Atohaer 60.15L nucil e is REAL and 61N mud\ of i+ is RIGGED. Because illeAitici.s__±6V44.1212thArif Me are co ridiculous, TAmohcler ifsorneahe Fl SE is pulling ibe—c+rihes._ If i+Is all fdke,±tyeLEAST tile ?e0Se_iti_____ clIdr3e can cia. -

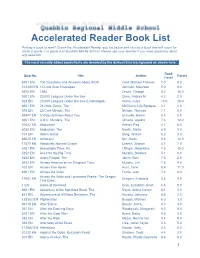

Accelerated Reader Book List

Accelerated Reader Book List Picking a book to read? Check the Accelerated Reader quiz list below and choose a book that will count for credit in grade 7 or grade 8 at Quabbin Middle School. Please see your teacher if you have questions about any selection. The most recently added books/tests are denoted by the darkest blue background as shown here. Book Quiz No. Title Author Points Level 8451 EN 100 Questions and Answers About AIDS Ford, Michael Thomas 7.0 8.0 101453 EN 13 Little Blue Envelopes Johnson, Maureen 5.0 9.0 5976 EN 1984 Orwell, George 8.2 16.0 9201 EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea Clare, Andrea M. 4.3 2.0 523 EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Unabridged) Verne, Jules 10.0 28.0 6651 EN 24-Hour Genie, The McGinnis, Lila Sprague 4.1 2.0 593 EN 25 Cent Miracle, The Nelson, Theresa 7.1 8.0 59347 EN 5 Ways to Know About You Gravelle, Karen 8.3 5.0 8851 EN A.B.C. Murders, The Christie, Agatha 7.6 12.0 81642 EN Abduction! Kehret, Peg 4.7 6.0 6030 EN Abduction, The Newth, Mette 6.8 9.0 101 EN Abel's Island Steig, William 6.2 3.0 65575 EN Abhorsen Nix, Garth 6.6 16.0 11577 EN Absolutely Normal Chaos Creech, Sharon 4.7 7.0 5251 EN Acceptable Time, An L'Engle, Madeleine 7.5 15.0 5252 EN Ace Hits the Big Time Murphy, Barbara 5.1 6.0 5253 EN Acorn People, The Jones, Ron 7.0 2.0 8452 EN Across America on an Emigrant Train Murphy, Jim 7.5 4.0 102 EN Across Five Aprils Hunt, Irene 8.9 11.0 6901 EN Across the Grain Ferris, Jean 7.4 8.0 Across the Wide and Lonesome Prairie: The Oregon 17602 EN Gregory, Kristiana 5.5 4.0 Trail Diary.. -

Genrefication Best Practices

Genrefication Best Practices Follett School Solutions ©2019 Contents Overview of Genrefication 4 What is genrefication? 4 About this guides 4 Getting help 4 What does a “typical” genrefication project entail? 4 What do I need to include in my plan? 5 Prepare and plan for the collection 5 Plan and prepare the physical library space 9 Plan and prepare the work of flipping the collection 9 Planning Your Library Space 11 Genre-organized shelf planning 11 Shelf-space calculations 11 Indicating genre on the shelves 13 Library signage 13 Using the Genre Collection Report 14 Elements of the report 14 How to use the Genre Collection Report 16 Adding Genre Data to Destiny 17 Genre Planning Checklist 22 Popular Fiction Genres, Titles and Authors 25 Adventure 25 Animal Stories 25 Classics 25 Dystopian 25 Fantasy 26 Graphic Novel 26 Historical Fiction 26 Horror/Scary Stories 26 Follett School Solutions ©2019 1 Humor 27 Mystery 27 Mythology 27 Poetry 27 Realistic Fiction 28 Romance 28 Science Fiction 28 Sports Fiction 28 Popular Nonfiction Genres, Titles and Authors 29 All About Me (Elementary) 29 Ancient World (Secondary) 29 Animals 29 Around the World (Elementary) 29 Biography 29 Business & Finance (Secondary) 30 Careers & College (Secondary) 30 Conservation & Environment (Secondary) 30 Cooking & Food 30 Criminal Justice & Law (Secondary) 30 Curiosities & Wonders (Secondary) 30 DIY 30 Dinosaurs (Elementary) 31 Drama (Secondary) 31 Earth Science (Secondary) 31 Economics (Secondary) 31 Fashion (Secondary) 31 Folklore (Elementary) 31 Fun Facts (Elementary) -

DIARY of a WIMPY KID by Jackie Filgo & Jeff Filgo Based on the Novel by Jeff Kinney

DIARY OF A WIMPY KID by Jackie Filgo & Jeff Filgo Based on the novel by Jeff Kinney TWENTIETH CENTURY FOX 2ND STUDIO DRAFT (2nd Revision) 10201 W. Pico Blvd. JANUARY 22, 2009 Los Angeles, CA 90035 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. COPYRIGHT ©2009 TWENTIETH CENTURY FOX FILM CORPORATION. NO PORTION OF THIS SCRIPT MAY BE PERFORMED, PUBLISHED, REPRODUCED, SOLD OR DISTRIBUTED BY ANY MEANS, OR QUOTED OR PUBLISHED IN ANY MEDIUM, INCLUDING ANY WEB SITE, WITHOUT THE PRIOR WRITTEN CONSENT OF TWENTIETH CENTURY FOX FILM CORPORATION. DISPOSAL OF THIS SCRIPT COPY DOES NOT ALTER ANY OF THE RESTRICTIONS SET FORTH ABOVE. FADE IN: 1 INT. GREG’S BEDROOM 1 BLACK SCREEN. Soft breathing. SUPER: “Monday” is scrawled across the screen in Greg’s handwriting. Then BLINDING LIGHT. RODRICK (O.S.) Greg. GREG’S POV: we find RODRICK HEFFLEY, an insolent sixteen- year-old, in our face. Rodrick is dressed for school. RODRICK (CONT’D) Greg! GREG (half asleep) What? Rodrick shakes Greg awake. RODRICK Get up, you’re going to be late. END POV to find GREG HEFFLEY in his twin bed. Greg is eleven or twelve, average height, and really thin. Rodrick is going to town with the shaking thing, basically bouncing him on his bed. GREG (fighting him off) Quit it, Rodrick! Why are you -- what am I late for? RODRICK Middle school, what do you think? Today’s your first day. Hurry up or Mom’s gonna lose it. Rodrick exits. Greg sighs. 2 INT. HEFFLEY KITCHEN 2 Greg, now dressed and ready for school, eats cereal and reads the comics with bleary eyes. -

Programming Ideas

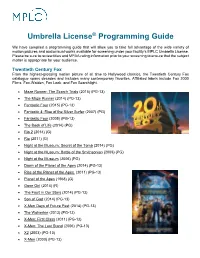

Umbrella License® Programming Guide We have compiled a programming guide that will allow you to take full advantage of the wide variety of motion pictures and audiovisual works available for screening under your facility’s MPLC Umbrella License. Please be sure to review titles and MPAA rating information prior to your screening to ensure that the subject matter is appropriate for your audience. Twentieth Century Fox From the highest-grossing motion picture of all time to Hollywood classics, the Twentieth Century Fox catalogue spans decades and includes many contemporary favorites. Affiliated labels include Fox 2000 Films, Fox-Walden, Fox Look, and Fox Searchlight. • Maze Runner: The Scorch Trials (2015) (PG-13) • The Maze Runner (2014) (PG-13) • Fantastic Four (2015) (PG-13) • Fantastic 4: Rise of the Silver Surfer (2007) (PG) • Fantastic Four (2005) (PG-13) • The Book of Life (2014) (PG) • Rio 2 (2014) (G) • Rio (2011) (G) • Night at the Museum: Secret of the Tomb (2014) (PG) • Night at the Museum: Battle of the Smithsonian (2009) (PG) • Night at the Museum (2006) (PG) • Dawn of the Planet of the Apes (2014) (PG-13) • Rise of the Planet of the Apes (2011) (PG-13) • Planet of the Apes (1968) (G) • Gone Girl (2014) (R) • The Fault in Our Stars (2014) (PG-13) • Son of God (2014) (PG-13) • X-Men Days of Future Past (2014) (PG-13) • The Wolverine (2013) (PG-13) • X-Men: First Class (2011) (PG-13) • X-Men: The Last Stand (2006) (PG-13) • X2 (2003) (PG-13) • X-Men (2000) (PG-13) • 12 Years a Slave (2013) (R) • A Good Day to Die Hard (2013) -

Diary of a Wimpy Kid Book #1 Teaching Guide

By Jeff Kinney Teaching guide Encourage self-expression, inspire student writing, spark critical thinking, explore writing in nontraditional formats, and much more. based on the first book in the #1 bestselling diary of a wimpy kid series by jeff kinney Includes: • Assessments • Teaching rationale • Student reproducible • Discussion questions • Writing prompts • Correlation to national and state standards Aligned with the Common Core State Standards and the NCTE/IRA English Language Arts Standards. DIARY OF A WIMPY KID®, WIMPY KID™, and the Greg Heffley design™ are trademarks of Wimpy Kid, Inc. All rights reserved. 1 About the Book This book is a journal—NOT a diary—belonging to Greg Heffley, a middle school student struggling to navigate among the morons, girls, and gorillas that fill his school. Greg figures he’s around the 52nd or 53rd most popular kid this year and soon to move up in the ranks. Though this middle school weakling works hard to figure out the angle that will always make things come out best for him, Greg’s schemes to gain popularity and status rarely seem to pay off. Especially when it comes to dealings with his best friend Rowley, who has Greg to thank for a broken hand and getting blamed for terrorizing a group of kindergartners. Throughout his journal, Greg shares all the misadventures of his middle school experience and his family life. From wrestling in gym with a weird classmate who shouts “Juice!” when he has to go to the bathroom to being chased by teenagers on Halloween (and losing all his candy when his father douses him with a trash can full of water) to the daily emptying of his little brother’s plastic potty, Greg acerbically chronicles his year, from the first awkward day of school to the last. -

January 9, 2018, 4 Viii

PIKES PEAK LIBRARY DISTRICT BOARD OF TRUSTEES JANUARY 9, 2018, 4 PM - PENROSE LIBRARY I. CALL TO ORDER II. ITEMS TOO LATE FOR THE AGENDA III. PUBLIC COMMENT (3 Minute Time Limit per Person) IV. CORRESPONDENCE AND COMMUNICATIONS A. Minutes (p. 1) B. Correspondence C. Events & Press Clippings (p. 10) V. REPORTS A. Friends of the Pikes Peak Library District Report (p. 12) B. Pikes Peak Library District Foundation Report (p. 13) C. Board Reports 1. Governance Committee Report 2. Internal Affairs Committee Report 3. Public Affairs Committee Report 4. Adopt-a-Department Reports 5. Board President’s Report D. Financial Report (p. 14) E. Public Services Report (p. 31) F. Circulation Report (p. 33) G. Chief Librarian’s Report (p. 39) VI. BUSINESS ITEMS A. Consent Items: Decision 18-1-1 (p. 41) Consent items shall be acted upon as a whole, unless a specific item is called for discussion. Any item called for discussion shall be acted upon separately as “New Business”. 1. New Hires (p. 41) 2. Resolution Designating Posting Places for 2018 Board Meetings (p. 42) 3. Resolution Designating the Official Custodian of Records (p. 43) 4. Disposition of PPLD Property (p. 46) 5. 2018 Contract/Vendor Approval (p. 50) 6. Conflict of Interest Statement (p. 58) 7. Insurance Policies (p. 60) 8. Auditor for Audit of 2017 Financial Records (p. 62) B. Unfinished Business C. New Business 1. Policy Update: Interlibrary Loan Policy: Decision 18-1-2 (p. 72) 2. Policy Update: Code of Conduct Policy: Decision 18-1-3 (p. 75) 3. Integrated Library System Migration to Software as a Service: Decision 18-1-4 (p. -

Diary of a Wimpy Kid: Old School Is a Graphic Novel 12) Do You Think This Book Is Funny? Why Or Why Not? Life Was Better in the Old Days

A U T H O R B I O * R E A D A L I K E S Jeff Kinney is an online game Big Nate: In A Class By Himself by Lincoln Peirce developer, designer, the creator of Poptropica.com and the #1 New York Times best-selling author and illustrator of the wildly popular Diary of a Wimpy Supremely confident middle-school Kid series. student Nate Wright manages to make getting detention from every one of his Born in Maryland in the 1970s, Jeff teachers in the same day seem like an spent his childhood in the Washington, D.C. area and achievement. moved to New England in 1995. As a young reader, Jeff was inspired by the books of Judy Blume, Beverly Cleary, Piers Anthony and J.R.R. Tolkien. Jeff attended the University of Maryland in the early $ # $ # $ # $ # $ # 1990s. It was there that he ran a comic strip called Middle School is Worse Than Meatloaf by Jennifer Holm "lgdoof" in the campus newspaper and knew that he wanted to be become a newspaper strip cartoonist. Although Jeff started writing down ideas for Diary of a Wimpy Kid in 1998, it wasn't until spring of 2007 that Ginny starts out with ten items on her his book was published — and quickly became a New to-do list for seventh grade, but notes, York Times bestseller, eventually reaching the number cartoons, and other "stuff" reveal what one spot. In 2010, Diary of a Wimpy Kid was made into seems like a thousand things that go a movie starring Zach Gordon as Greg Heffley. -

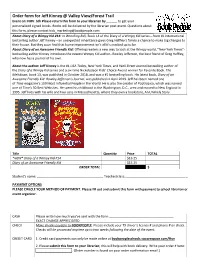

Order Form for Jeff Kinney @ Valley View/Forest Trail Event On: NOV

Order form for Jeff Kinney @ Valley View/Forest Trail Event on: NOV. 5th Please return this form to your librarian by ______ to get your personalized signed books. Books will be delivered by the librarian post-event. Questions about this form, please contact [email protected] About Diary of a Wimpy Kid #14: In Wrecking Ball, Book 14 of the Diary of a Wimpy Kid series—from #1 international bestselling author Jeff Kinney—an unexpected inheritance gives Greg Heffley’s family a chance to make big changes to their house. But they soon find that home improvement isn’t all it’s cracked up to be. About Diary of an Awesome Friendly Kid: Offering readers a new way to look at the Wimpy world, "New York Times"- bestselling author Kinney introduces the newest Wimpy Kid author--Rowley Jefferson, the best friend of Greg Heffley, who now has a journal of his own. About the author: Jeff Kinney is the #1 USA Today, New York Times, and Wall Street Journal bestselling author of the Diary of a Wimpy Kid series and a six-time Nickelodeon Kids’ Choice Award winner for Favorite Book. The Meltdown, book 13, was published in October 2018, and was a #1 bestselling book. His latest book, Diary of an Awesome Friendly Kid: Rowley Jefferson’s Journal, was published in April 2019. Jeff has been named one of Time magazine’s 100 Most Influential People in the World. He is also the creator of Poptropica, which was named one of Time’s 50 Best Websites. He spent his childhood in the Washington, D.C., area and moved to New England in 1995. -

Diary of a Wimpy Kid :: Rogerebert.Com :: Reviews 10-03-30 9:05 PM

Diary of a Wimpy Kid :: rogerebert.com :: Reviews 10-03-30 9:05 PM movie reviews Reviews Great Movies Answer Man People Commentary Festivals Oscars Glossary One-Minute Reviews Letters Roger Ebert's Journal Scanners Store News Sports Business Entertainment Classifieds Columnists search DIARY OF A WIMPY KID (PG) Ebert: Users: You: Rate this movie right now Site Web Search powered by YAHOO! GO advanced » tips » register You are not logged in. Log in » Subscribe to weekly newsletter » in theaters times & tickets Grayson Russell, Zachary Gordon and Robert Capron in "Diary of latest reviews a Wimpy Kid." Fandango Chloe Search movie showtimes and buy Diary of a Wimpy Kid Greenberg tickets. Hot Tub Time Machine BY ROGER EBERT / March 17, 2010 How to Train Your Dragon The Most Dangerous Man in America It is so hard to do a movie about us Mother like this well. "Diary of a cast & credits Waking Sleeping Beauty About the site » Wimpy Kid" is a PG-rated comedy about the hero's 45365 Site FAQs » first year of middle school, Greg Zachary Gordon Leaves of Grass and it's nimble, bright and Rowley Robert Capron more current releases » Contact us » funny. It doesn't dumb Angie Chloe Moretz down. It doesn't patronize. Mrs. Heffley Rachael Harris one-minute movie reviews Email the Movie It knows something about Mr. Heffley Steve Zahn Answer Man » human nature. It isn't as Rodrick Devon Bostick still playing good as "A Christmas Chirag Gupta Karan Brar Story," as few movies are, Fregley Grayson Russell on sale now but it deserves a place in Brooklyn's Finest Colin Alex Ferris the same sentence.