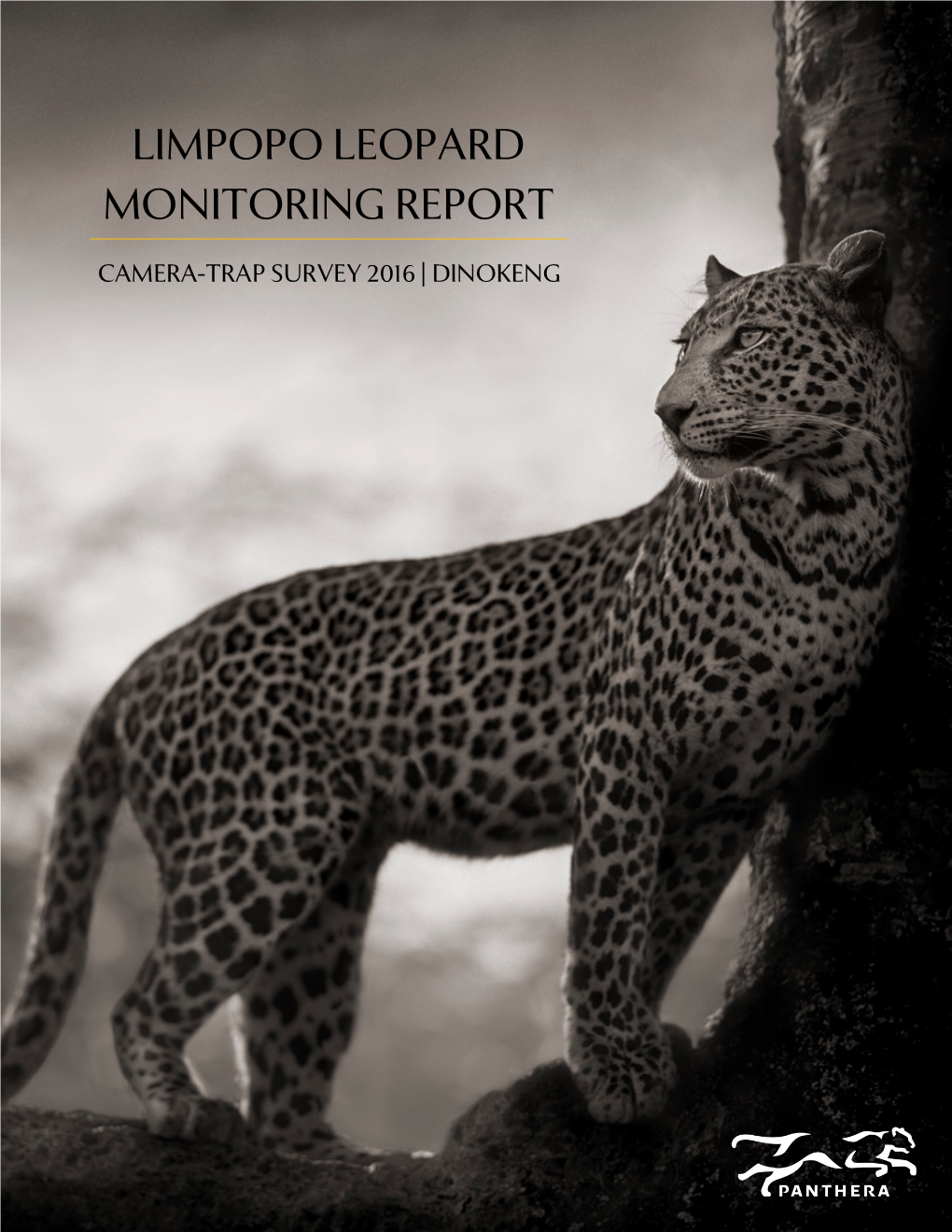

Limpopo Leopard Monitoring Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

South Africa Travel Guide 2017

South Africa Travel Guide 2017 1 From the Editor... After a few failed attempts at collecting travel information about South Africa, I decided it would be a great idea to publish my own South Africa Travel Guide. It has taken me about 3 years to assemble this valuable publication (in between extra hours in the CLO Office and publishing JJ’s and Classifieds, and more Classi- fieds, and more JJ’s). Realistically, I thought I would lose my mind if I heard, “I will send over travel brochures ‘just now’” one more time... It has been a lot of work, but being in the CLO Office is the reason that I started this venture in the first place. My favorite part of working in the CLO Office is helping people who are searching for travel information. There is no greater reward as the Editor of the Jacaranda Journal, than to hear that one of my readers has booked a vacation or some sort of adventure because of a travel story or advice from our office. Travelling means taking a break from everyday routines and just enjoying life. I personally believe that there is so much benefit to travel, which is why I am hoping this Guide entices you to travel more. Travel gives us better perspective, it makes us more adaptable and adventurous, and it just makes people happy. We are in a unique position, living life in the Foreign Service, and one of the greatest benefits is seeing the world. We get the opportunity to see places we would never have dreamed of and even better, we get to share them sometimes with friends and family. -

In Dinokeng Game Reserve, Gauteng, South Africa

Early post-release movement of reintroduced lions (Panthera leo) in Dinokeng Game Reserve, Gauteng, South Africa Sze-Wing Yiu1,3 & Mark Keith2 & Leszek Karczmarski1,* & Francesca Parrini3 1 The Swire Institute of Marine Science, School of Biological Sciences, The University of Hong Kong, Cape d‟Aguilar, Shek O, Hong Kong 2 Centre for Wildlife Management, University of Pretoria, Private Bag X20, Hatfield, Pretoria 0028, South Africa 3 Centre for African Ecology, School of Animal, Plant and Environmental Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Private Bag 3, Wits 2050, South Africa * Correspondence to: Leszek Karczmarski; [email protected] Abstract Reintroductions have been increasingly used in carnivore conservation. Animal movement influences fitness and survival and is the first behavioural response of reintroduced animals to „forced dispersal‟ in a new habitat. However, information available on early post-release movement of reintroduced carnivores remains limited. We studied movements of 11 reintroduced lions (Panthera leo) in Dinokeng Game Reserve, South Africa, in their first season of release and investigated changes in movements over time. Movement patterns of lions were more diverse than expected and varied between sexes and individual groups. Some lion groups returned to the area surrounding the release site after initial exploration and avoided human settlements, suggesting that vegetation and human disturbances influenced dispersal upon release. Cumulative home range size continued to increase for all lions despite individual differences in movement patterns. We highlight the importance of considering the variation in individual-specific behaviour and movement patterns to assess early establishment and reintroduction success. Keywords CarnivoreReintroductionDispersalExplorationHome rangeSpace use Introduction Dispersal is a key process in animal movement ecology and can happen more than once at any stage in an animal‟s lifespan (Santini et al. -

Sa Yearbook 2009/10 Tourism Tourism 22

SA YEARBOOK 2009/10 TOURISM TOURISM 22 South Africa has the world’s richest floral kingdom 5 946 (1,8%); West Africa 5 649 (1,7%); and North and a vast variety of endemic and migratory birds. Africa 951 (0,3%). It is also home to one-sixth of the world’s marine species and has more species of wild animals Business tourism than North and South America or Europe and Asia South Africa has always been popular with together. Its diversity, sunny skies and breathtak- international leisure travellers, but it is also fast ing scenery make it a popular holiday destination. becoming a preferred business tourism destina- The 2010 World Cup affords South Africa a once- tion. Large international companies are eager to in-a-lifetime opportunity to showcase the best the host international events, conferences and trade country has as a tourist destination. expos in the country, and business travellers are In 2009, the Department of Environmental just as willing to attend. Affairs and Tourism became the Department of The Department of Trade and Industry has Tourism, emphasising the importance of this identified business tourism as a niche tourism sector. segment with growth potential. Tourism has been identified as one of the key For the past few years, South African Tourism economic sectors with excellent potential for (SAT) has focused on building the leisure market growth. with business tourism, previously known as the About 9,6 million foreign tourists visited South Mice (Meetings, Incentives, Conferences and Exhi- Africa in 2008, a 5,5% increase over the 9,1 mil- bitions) industry, playing a smaller role. -

Dinokeng Project: Department of Economic Development Environmental Management Framework and Environmental Management Plan for T

DINOKENG PROJECT: DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT FRAMEWORK AND ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT PLAN FOR THE DINOKENG PROJECT AREA Final Draft for Public Circulation October 2009 DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT FRAMEWORK AND ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT PLAN FOR THE DINOKENG PROJECT AREA Prepared By: Contact: Bohlweki-SSI Environmental Janet Loubser P O Box 867 Tel: (012) 367 5800 Gallo Manor, 2052 Email: [email protected] EXECUTIVE SUMMARY preserve ecosystem services such as stormwater management, pollination, The Dinokeng Project aims to create a climatic control and aesthetic desirability. self-sustaining local economy in the north- eastern reaches of the Gauteng Province. An audit of mining activities in the Core to the project is the establishment of Dinokeng Area identified many mining a Big-5 collaborative game reserve, with a sites, both active and inactive, that will mix of land uses in the surrounding area affect other land uses and overall ranging from high density urban development plans for the area. Of development to diverse tourism particular consequence are mining establishments. activities and prospecting rights within sensitive areas or areas that are earmarked In support of this objective, this for land uses that are generally Environmental Management incompatible with surface mining Framework is compiled, to ensure that activities. The information should now be the development patterns take cognisance used to facilitate stakeholder of and do not compromise the long term communication as well as concrete viability of the natural and social resources monitoring and control over mining of the area. In essence, it defines a spatial activities. development structure that can be supported by the natural resource base and The delineation of management zones which most closely matches the social and compares the various layers of ‘status quo’ developmental desires of the local and ‘desired state’ information to highlight communities. -

Africa Adventure Ride

Africa Adventure Ride: 18 Days Victoria Falls to Cape Town Information Kit Zimbabwe, Botswana, South Africa and Lesotho: Africa is one of the world’s true last frontiers, an outstanding bikers’ destination “This was the best trip I have even been on! We saw parts of Africa that few will see.” - Shelli, Canada Few places in the world have captured the imagination of adventurers like Africa. Discover a landscape full or amazing wildlife, the likes that can be seen nowhere else on earth, a landscape of epic deserts, impossibly rugged mountains, fertile valleys stuffed with wineries and dramatic waterfalls. Ride with and be entertained by Charley Boorman and learn about what you are seeing from qualified wildlife guide Billy Ward. Itinerary Day One: Victoria Falls Today is about receiving and familiarising ourselves with the bikes. Meeting each other and spending some time learning how to properly use the GPS units fitted to each bike with the preloaded routes. This day is about meeting Charley Boorman and Billy Ward, his friend, manager and second guide rider. Day Two: Elephant Sands We depart the amazing Victoria Falls Hotel and ride straight to the remote border post of Pandamatenga where we cross into Botswana. We have this border to ourselves as the horde of other tourists are at a different border! The ride to the border is via a superb dirt track through the Kazuma Forest Reserve where elephant and lion have been spotted. We skirt the Hwange National Park once in Botswana and may see elephants, antelope and even Lion. Day Three: Martins Drift After the dirt of yesterday, its paved road all day today. -

Operation Wallacea Have Been Appointed to Provide Data on a Range of Research Outputs with the Following Objectives

South Africa Schools Booklet 2021 Masebe & Dinokeng Contents 1. Study Area & Overall Research Aims ............................................................................... 2 2. Itinerary ......................................................................................................................... 3 3. Activities & Schedule at Masebe Nature Reserve .............................................................. 3 4. Research Objectives, Activities & Schedule at Dinokeng Game Reserve ............................ 6 6. African Wildlife Management Course ............................................................................... 8 7. Academic Benefits ....................................................................................................... 10 8. Additional Reading ....................................................................................................... 11 Last updated: 03 November 2020 South Africa Schools Booklet – Masebe & Dinokeng 1 1. Study Area & Overall Research Aims South Africa is the best place in the world if you want to learn about how to make wildlife conservation work financially. Income from game management and ecotourism revenue has meant that there is an ever- expanding network of game reserves that also benefit much other wildlife besides the game species. For the 2021 season there is the choice of options for school groups. This booklet will focus on the expedition involving one week undertaking wilderness training in Masebe Nature Reserve and one week helping with research -

Assumptions About Fence Permeability Influence Density Estimates For

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Assumptions about fence permeability infuence density estimates for brown hyaenas across South Africa Kathryn S. Williams1,2,9, Samual T. Williams1,2,3,4,9*, Rebecca J. Welch5, Courtney J. Marneweck5, Gareth K. H. Mann7,8, Ross T. Pitman7,8, Gareth Whittington‑Jones7, Guy A. Balme7,8, Daniel M. Parker5,6 & Russell A. Hill1,2,3 Wildlife population density estimates provide information on the number of individuals in an area and infuence conservation management decisions. Thus, accuracy is vital. A dominant feature in many landscapes globally is fencing, yet the implications of fence permeability on density estimation using spatial capture‑recapture modelling are seldom considered. We used camera trap data from 15 fenced reserves across South Africa to examine the density of brown hyaenas (Parahyaena brunnea). We estimated density and modelled its relationship with a suite of covariates when fenced reserve boundaries were assumed to be permeable or impermeable to hyaena movements. The best performing models were those that included only the infuence of study site on both hyaena density and detection probability, regardless of assumptions of fence permeability. When fences were considered impermeable, densities ranged from 2.55 to 15.06 animals per 100 km2, but when fences were considered permeable, density estimates were on average 9.52 times lower (from 0.17 to 1.59 animals per 100 km2). Fence permeability should therefore be an essential consideration when estimating density, especially since density results can considerably infuence wildlife management decisions. In the absence of strong evidence to the contrary, future studies in fenced areas should assume some degree of permeability in order to avoid overestimating population density. -

WTSA Volunteering Dinokeng Game Reserve 10.05.2018 Page 1\10

Country: South Africa Host Organisation: WTSA Volunteering Date: May 2018 Name of Project: Dinokeng Game Reserve – Hammanskraal (Gauteng) Project Type: Wildlife Conservation, Animal Behaviour and Reserve Management Project Project address: Dinokeng Game Reserve R734, Hammanskraal Pretoria, Gauteng 0400 International airport for OR Tambo International Airport in Johannesburg (JHB) is the international gateway, flight arrivals: from where volunteers are collected and transported by vehicle on a 100km journey to camp. Dinokeng Game Reserve is located approx 45km north of the urban center of Pretoria, Gauteng. Phone: +27 21 Email: [email protected] Web: www.worktravelsa.org 8519494 [email protected] www.wei.org.za Unit Stephan Contact +27 (0)21 851 9494 After Mobile/Emergency: Manager van Details: Mobile: Hours +27 (0)76 832 1219 Straaten +27 (0)82 338 9970 Norman Volunteer Contact +27 (0)60 506 4501 Jafta Coordinator Details: Christmas & New Year Period when no Note: are quiet periods when None volunteers are accepted: some staff may be on leave. 3 Staff on the project: Permanent Volunteers get a Yes, from If yes, name of the Volunteer Coordinator certificate at the end of WTSA responsible person: their stay: (yes/no) 2 weeks; 1; 1.5; 2; 2.5; 3 months - Maximum # of volunteers 10 Project Duration: start/fin dates on 1 st and 15 th every at any time: month. Name and country of WTSA Volunteering is the only organization which recruits student volunteers for these Organization(s): conservation research and reserve management work at Dinokeng Game Reserve . The reserve is however also used for many tourist lodges and adventure activities operated by other suppliers and land owners inside the reserve. -

16-DAY SUBTROPICAL SOUTH AFRICA TRIP REPORT, 10 – 25 March 2017

SOUTH AFRICA: 16‐DAY SUBTROPICAL SOUTH AFRICA TRIP REPORT, 10 – 25 March 2017 By Jason Boyce Drakensberg Rockjumper – One of the birds of the trip! www.birdingecotours.com [email protected] 2 | T R I P R E P O R T Subtropical South Africa Trip Report March 2017 TOUR ITINERARY Overnight Day 1 – Arrival and birding Umhlanga Gateway Country Lodge, Umhlanga Day 2 – Umhlanga to Underberg KarMichael Guest Farm, Himeville Day 3 – Sani Pass KarMichael Guest Farm, Himeville Day 4 – Southern Drakensberg to Eshowe Birds of Paradise B&B, Eshowe Day 5 – Ongoye, Mtunzini and Amatikulu Birds of Paradise B&B, Eshowe Day 6 – Eshowe, Dlinza to St Lucia Ndiza Lodge, St Lucia Day 7 – St Lucia Wetland Park Ndiza Lodge, St Lucia Day 8 – St Lucia to Mkhuze Game Reserve Mantuma Camp, Mkhuze Day 9 – Mkhuze Game Reserve Mantuma Camp, Mkhuze Day 10 – Mkhuze to Wakkerstroom Wetlands Country House, Wakkerstroom Day 11 – Wakkerstroom birding Wetlands Country House, Wakkerstroom Day 12 – Wakkerstroom to Skukuza, KNP Kruger National Park, Skukuza Day 13 – Southern Kruger National Park Kruger National Park, Skukuza Day 14 – Kruger National Park to Dullstroom Linger Longer, Dullstroom Day 15 – Dullstroom to Dinokeng Game Reserve Leopardsong Game Lodge, Dinokeng Day 16 – Rust de Winter to Johannesburg airport Flight home OVERVIEW This was a tour with incredible diversity, varying habitats, enjoyable company, and a host of endemic South African bird species. Our 16-day ‘Subtropical South Africa’ tour gave us 397 species of birds, with an additional 15 species being heard only. We also saw 37 mammal species, interesting reptiles, and a few rare South African butterflies. -

Itinerary 1 Vet Student Study Abroad South Africa

VET STUDENT STUDY ABROAD SOUTH AFRICA 15 Days| 14 Nights South Africa Veterinary Student Program (2019 Students participates were third year students from the College of Veterinary Medicine University of Missouri, USA) • The program was established to provide “hands-on” experience for third year veterinary students to accomplish externship hours to qualify for preceptorship hours applied towards future applications of licensure for the state of Missouri. The experience consisted of: • Training in the use of immobilization and reversing agents for tranquilization of wildlife in the bush of South Africa; three methods of darting animals were explored and were utilized during this experience • Helicopter darting of antelope, rhino and elephants and ground darting of antelope and big cats • Activities involved: wildebeest, zebra, eland were tranquilized to remove research collars as research data had been collected and research project completed; rhinos darted/tranquilized for ear notching identification; elephants darted/tranquilized for transport to another location; impala darted/tranquilized for ultrasound examination for pregnancy - trans-abdominally, trans-rectally and trans-vaginally techniques were used; sable antelope darted for semen collection and evaluation; cheetah darted after escaping reserve and returned to reserve; lions darted for dental evaluation inclusive of dental radiographs, extractions and root canals; lions darted and anesthetized for ovariohysterectomy (spay); lions radiographed for cervical lesions that were related -

Habitat Selection of African Elephants (Loxodonta Africana)

HABITAT SELECTION OF AFRICAN ELEPHANTS (LOXODONTA AFRICANA) AFTER REINTRODUCTION IN DINOKENG GAME RESERVE Jeanette de Hoog A Research Report submitted to the Faculty of Science, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Johannesburg, May 2014 DECLARATION i ABSTRACT Conservation has led to African elephants (Loxodonta africana) being reintroduced to small game reserves. However, only a few studies have been done on how elephants react to their new environment after a translocation. Dinokeng Game Reserve introduced a herd of 10 elephants (Loxodonta Africana) in October 2011. Using Global Positioning System collar locations of one female elephant, I aimed to determine whether an elephant’s exploration resulted in an expansion of its home range as the elephant settled in its new environment. Secondly, I aimed to determine how the use of resources and conditions in an elephant’s environment changed from release to the end of the study period. To achieve my first objective, I calculated the elephant’s daily distance movement distances and home ranges over 16-day and seasonal periods. I used logistic regression to assess the habitat selection of the elephant over the study period. The results of the research demonstrated that the elephant slowly explored its new environment, which resulted in an expansion of its home range over time. However, it took almost two years before the elephant displayed signs of settling in its home range. The elephant used habitats further away from buildings, closer to fence boundaries and water sources, with low elevation and high greenness at the start of the study. -

Spatial Behaviour of Reintroduced Male Buffalo and Their

Spatial behaviour of reintroduced male buffalo and their response to predators By Nkanyiso Cele 565778 Supervisors: Dr. Yiu, Prof. Parrini, & Dr. Merlo University of the Witwatersrand School of Geography, Archaeology & Environmental Studies 29 May 2019 Abstract Understanding spatial behavior of reintroduced animals is critical for better informed management decisions. Rapid growth of human population has caused human and wildlife species conflict over the years. Exploitation of resources for human consumption destroys and fragments natural habitats, decreases species diversity and distribution and fast-tracks the rate of extinction. Large herbivores are often translocating and reintroduced as a process of re- establishment. Reintroduction success depends on numerous factors, which include; the handling and capturing procedure, availability of food, habitat quality, the interaction of the species at the release location, and most importantly, post release monitoring. The adaptive local convex hull (a-LoCoH) was applied to study home range establishment and utilization of the two-male buffalos in the Dinokeng Game Reserve, South Africa from 2012 to 2014. Movement patterns were similar between the two-male buffalo over the same time period, with home range establishment in the core and 95% reaching 4.11 km2 and 19.36 km2 for male buffalo 427 and 6.20 km2 and 41.79 km2 for male buffalo 455, respectively. Stabilization of movement pattern became apparent after 180 days of reintroduction suggesting change in movement pattern/behavior from large scale exploration to small scale exploration. Furthermore, the buffalo’s showed avoidance and seasonal avoidance of built-up and lion probability of occurrence areas, respectively. The study shows the importance of biotic and abiotic factors that influence buffalo movement pattern and resource selection.