The Red Swimsuit: Essays

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

You Ordered Your Crew to Attack Me!!!

1/31/2020 Machine Gun Kelly Sued for Bodyguards' Beatdown on Actor 'G-Rod' GOT A TIP? TMZ Live: Click Here to Watch! Kick O Super Bowl Weekend Dog The Bounty Hunter's Kids Get Ready For 'Taylor Swi: Jake Paul Destroys AnEsonGib With These Stars In Miami! Slam Proposal To Beth's Miss Americana' ... See Her In 1st Round KO, KSI Next?! | Friend Moon Through The Years! TMZ NEWSROOM Machine Gun Kelly Sued for Bodyguards' Beatdown on Actor 'G-Rod' MACHINE GUN KELLY Sued By Actor 'G-Rod' ... YOU ORDERED YOUR CREW TO ATTACK ME!!! 719 525 6/7/2019 3:04 PM PT https://www.tmz.com/2019/06/07/machine-gun-kelly-sued-bodyguards-battery-gabriel-rodriguez/ 1/8 1/31/2020 Machine Gun Kelly Sued for Bodyguards' Beatdown on Actor 'G-Rod' EXCLUSIVE Machine Gun Kelly's goons ganged up on a guy, and beat the hell outta him -- on video -- and now the victim's suing the rapper, claiming he ordered the attack. We broke the story ... Gabriel "G-Rod" Rodriguez confronted MGK back in September at an Atlanta restaurant and called him a "p***y" because he was pissed about Kelly's beef with Eminem. 9/15/18 0:00 / 1:02 BEATDOWN FOOTAGE ATL Police Department Later in the evening at a Hampton Inn, video footage shows G-Rod getting jumped and viciously body slammed, kicked and punched by a bunch of dudes allegedly in MGK's crew. At least 3 of the individuals were ID'd and charged with misdemeanor battery, but cops said MGK was in the clear because he wasn't a part of it. -

Sources & Data

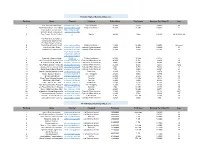

YouTube Highest Earning Influencers Ranking Name Channel Category Subscribers Total views Earnings Per Video ($) Age 1 JoJo https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCeV2O_6QmFaaKBZHY3bJgsASiwa (Its JoJo Siwa) Life / Vlogging 10.6M 2.8Bn 569112 16 2 Anastasia Radzinskayahttps://www.youtube.com/channel/UCJplp5SjeGSdVdwsfb9Q7lQ (Like Nastya Vlog) Children's channel 48.6M 26.9Bn 546549 6 Coby Cotton; Cory Cotton; https://www.youtube Garrett Hilbert; Cody Jones; .com/user/corycotto 3 Tyler Toney. (Dude Perfect) n Sports 49.4M 10Bn 186783 30,30,30,33,28 FunToys Collector Disney Toys ReviewToys Review ( FunToys Collector Disney 4 Toys ReviewToyshttps://www.youtube.com/user/DisneyCollectorBR Review) Children's channel 11.6M 14.9Bn 184506 Unknown 5 Jakehttps://www.youtube.com/channel/UCcgVECVN4OKV6DH1jLkqmcA Paul (Jake Paul) Comedy / Entertainment 19.8M 6.4Bn 180090 23 6 Loganhttps://www.youtube.com/channel/UCG8rbF3g2AMX70yOd8vqIZg Paul (Logan Paul) Comedy / Entertainment 20.5M 4.9Bn 171396 24 https://www.youtube .com/channel/UChG JGhZ9SOOHvBB0Y 7 Ryan Kaji (Ryan's World) 4DOO_w Children's channel 24.1M 36.7Bn 133377 8 8 Germán Alejandro Garmendiahttps://www.youtube.com/channel/UCZJ7m7EnCNodqnu5SAtg8eQ Aranis (German Garmendia) Comedy / Entertainment 40.4M 4.2Bn 81489 29 9 Felix Kjellberg (PewDiePie)https://www.youtube.com/user/PewDiePieComedy / Entertainment 103M 24.7Bn 80178 30 10 Anthony Padilla and Ian Hecoxhttps://www.youtube.com/user/smosh (Smosh) Comedy / Entertainment 25.1M 9.3Bn 72243 32,32 11 Olajide William Olatunjihttps://www.youtube.com/user/KSIOlajidebt -

Nate Robinson Vs Jake Paul Will Serve As the Co-Main Event for Mike Tyson Vs Roy Jones Jr

FIGHT OVERVIEW Nate Robinson Vs Jake Paul will serve as the Co-Main Event for Mike Tyson Vs Roy Jones Jr. Pay Per View This event will be one of the most highly anticipated and viewed Boxing PPV’s of all-time. The bout is set to pair the 3 Time NBA Slam Dunk Champion and 11 Year NBA Veteran against the Disney Channel Actor turned Youtube Sensation verses each other in an 6 round Professional boxing match. The event takes place on November 28th NATE ROBINSON is looking to partner with your brand to showcase the company likeness on his in-ring shorts, lead up training videos, Instagram campaigns, and more. PROMOTIONAL POSTER VIEWERSHIP Jake Paul’s last event received 2.25 Million live Pay-Per-View streams, and currently has over 75 Million Youtube views to date. It was the LARGEST viewed non-professional boxing match of all time. This event is set to surpass those numbers. Aside from the larger than life headliners Mike Tyson and Roy Jones Jr, Triller has acquired some of the top musical artists in the industry to perform between each match. The fight will air through In-Demand Pay-Per-View / Triller, and has already been covered on Sports Center, Bleacher Report, CBS, NBC, Yahoo, TMZ and more. https://www.legendsonlyleague.com/ AUDIENCE REACH Instagram Followers: Instagram Followers: 2.3M 13.2M Demographic by Age: Demographic by Age: 13-17 Years 6% 13-17 Years 11% 18-24 Years 33% 18-24 Years 34% 25-34 Years 37% 25-34 Years 23% 35-44 Years 15% 35-44 Years 20% 45-54 Years 5% 45-54 Years 8% 55-64 Years 1% 55-64 Years 2% 65+ Years 1% 65+ Years 2% SPONSORSHIP OPPORTUNITIES IN-RING ACTIVATION All In-Ring activations include (2) Instagram feed post + (2) Instagram story post - In-Ring Shorts (Front) - In-Ring Shorts (Back) - Boxing Gloves - In-Ring Socks - Towels - Water Bottle - Mouth Guard ADDITIONAL ACTIVATION - Press Conference - Pre-fight Training Video Integration - Social Media Campaign A La Carte options available . -

Alien Boy Invades Nickelodeon in New out of This World Comedy, Marvin Marvin, Starring Lucas Cruikshank, Premiering Saturday, Nov

Alien Boy Invades Nickelodeon in New Out of This World Comedy, Marvin Marvin, Starring Lucas Cruikshank, Premiering Saturday, Nov. 24, at 8:30 Pm (ET/PT) SANTA MONICA, Calif., Nov. 9, 2012 /PRNewswire/ -- Nickelodeon premieres a brand-new out of this world live-action comedy series, Marvin Marvin, on Saturday, Nov. 24, at 8:30 p.m. (ET/PT). Starring internet sensation Lucas Cruikshank in his first lead role since the beloved Fred Figglehorn, the half-hour multi-camera series follows the adventures of Marvin, an intergalactic alien teenager who clumsily tries to adapt to his new life on Earth. Marvin Marvin will air regularly on Saturdays at 8:30 p.m. (ET/PT) on Nickelodeon. (Photo: http://photos.prnewswire.com/prnh/20121109/NY09637 ) "Lucas' impressive comedic talents and creativity put him in a class of his own," said Paula Kaplan, Executive Vice President of Current Series, Nickelodeon. "We're incredibly excited to continue our relationship with him and know his fans will enjoy seeing this quirky new character and the rest of this talented cast in this fun new comedy." Marvin Marvin follows the adventures of a teenage alien with special powers named Marvin (Cruikshank) who was sent to Earth by his parents in order to protect him from evil invaders on his home planet, Klooton. Under the supervision of his new human parents, Bob (Pat Finn, The Middle) and Liz (Mim Drew, The Practice), Marvin tries to adjust to life on Earth as a typical American teenager. Helping him navigate Earth's unfamiliar social customs are Marvin's human siblings Teri (Victory Van Tuyl, Supah Ninjas) and Henry (Jacob Bertrand, ParaNorman) and his mischievous grandfather, Pop-Pop (Casey Sander, The Big Bang Theory). -

“Wasn't Even on My Radar”: Increasing Parental Mediation Of

Title “Wasn't even on my radar”: Increasing Parental Mediation of Influencer Marketing Behaviors in 35 Minutes with a Brief Theory of Planned Behavior informed Online Randomized Controlled Intervention Author Paul Rohde Affiliation Department of Media and Communication, London School of Economics and Political Science, Houghton St, Holborn, London WC2A 2AE, United Kingdom Keywords Young Consumer Marketing, Parental Mediation, Marketing Literacy, Influencer Marketing, Persuasion Knowledge, Theory of Planned Behavior, Behavioral Change Techniques, Mechanisms of Action Data https://osf.io/3xkhn/files/ Paul Rohde, 2020 – TPB-informed RCT on Parental Mediation of Influencer Marketing Abstract Online marketing to humans in their childhood, adolescent and early adulthood is an increasingly important research topic because it can on a larger scale than previously possible with traditional marketing lead to undesirable outcomes (e.g., obesity) and target more ethical grey zones between questionable, unfair and deceptive marketing to achieve its goals (Buijzen & Valkenburg, 2005; De Pauw et al., 2019). The largest recent research trend and solution to address the problems related to online young consumer marketing was the establishment of online marketing disclosure policies (De Veirman et al., 2019; FTC, 2017; Gürkaynak et al., 2018; Riefa & Clausen, 2019). Disclosures have their merits, but also shortcomings. In particular, increased process fairness (i.e., awareness of the selling intent) appears not to be enough to diminish undesirable outcomes because young consumers also need the knowledge and the skills to counter the undesirable effects resulting from marketing exposures (De Pauw et al., 2019; Isaac & Grayson, 2019; Jung & Heo, 2019; Youn & Shin, 2019). In intervention research targeting the increase of knowledge and skills of children, the largest yet comparatively small trend are school-based interventions (De Jans et al., 2019; Nelson, 2016; O’Rourke et al., 2019; Truman & Elliott, 2019). -

Jake Paul Vs. Gib Ahead of Jan. 30 Grudge Match on Dazn

DAZN TO PRESENT 40 DAYS: JAKE PAUL VS. GIB AHEAD OF JAN. 30 GRUDGE MATCH ON DAZN NEW YORK – Jan. 23, 2019 – DAZN Originals will present the latest edition of its training camp series, 40 DAYS: JAKE PAUL VS. GIB, an in-depth look at YouTube stars Jake “The Problem Child” Paul and “7-Figure Gibber” AnEsonGib ahead of their Jan. 30 professional boxing debuts, which will serve as the co-main event to a special Thursday night edition of world class boxing, exclusively on DAZN. 40 DAYS: JAKE PAUL VS. GIB will debut on each fighter’s YouTube channel today, Jan. 23, one week before the two settle the score in Miami prior to the big game. The 25-minute episode will also be available on the DAZN platform in addition to DAZN and Matchroom Boxing’s YouTube channels. This edition of 40 DAYS provides a revealing look at each fighter and their road to the Jan. 30 grudge match. DAZN takes viewers from Jake Paul’s rise to stardom via Vine and YouTube through to his training camp at California’s Big Bear Mountain where he is escaping his fame to prepare with three-division world champion “Sugar” Shane Mosley. Meanwhile, Gib’s high- energy antics and his path to overcoming obesity are detailed as he trains in Las Vegas with professional fighter and KSI’s head trainer Viddal Riley. “Big Bear is high altitude and no distractions, you can’t escape thinking about boxing there,” said Jake Paul. “Training with Shane Mosley, just everything clicked, and everything felt right. -

Deconstructing Social Media Influencer Marketing in Long- Form Video Content on Youtube Via Social Influence Heuristics

“It’s Selling Like Hotcakes”: Deconstructing Social Media Influencer Marketing in Long- Form Video Content on YouTube via Social Influence Heuristics Purpose – The study examines the ability of social influence heuristics framework to capture skillful and creative social media influencer (SMI) marketing in long-form video content on YouTube for influencer-owned brands and products. Design/methodology/approach – The theoretical lens was a framework of seven evidence-based social influence heuristics (reciprocity, social proof, consistency, scarcity, liking, authority, unity). For the methodological lens, a qualitative case study approach was applied to a purposeful sample of six SMIs and 15 videos on YouTube. Findings – The evidence shows that self-promotional influencer marketing in long-form video content is relatable to all seven heuristics and shows signs of high elaboration, innovativeness, and skillfulness. Research limitations/implications – The study reveals that a heuristic-based account of self- promotional influencer marketing in long-form video content can greatly contribute to our understanding of how various well-established marketing concepts (e.g., source attractivity) might be expressed in real-world communications and behaviors. Based on this improved, in- depth understanding, current research efforts, like experimental studies using one video with a more or less arbitrary influencer and pre-post measure, are advised to explore research questions via designs that account for the observed subtle and complex nature of real-world influencer marketing in long-form video content. Practical implications – This structured account of skillful and creative marketing can be used as educational and instructive material for influencer marketing practitioners to enhance their creativity, for consumers to increase their marketing literacy, and for policymakers to rethink policies for influencer marketing. -

HHS Magazine Fall / Winter 2015-16

HIHHS Magazine - LITE Fall / Winter 2015-16 Hi-Lite Staff Ben Geyer Editor Emmalee Stipe Writer/Photos Kayla Enders Writer/Photos Kamryn Pack Writer Julia Hoon Writer Bella Lepique Writer Erika Ward Writer Bill Sheets Writer Special thanks to Mr. Ruff’s Honors English 12 students and Mrs. Nec’s Honors English 9 students for contributing articles, and to Colleen & Company for contributing photographs. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS What Page Is That On? News Page Entertainment Page Gratz Fair Queen 4 Movie Reviews for 2016 19 Mini Thon/All-Nighter 5 Book Reviews for 2016 20 Homecoming Pep Rally 6 Music Reviews for 2016 21 Homecoming Court 7 Halifax Gala/ TV Night 8 Sports Page Halloween Festivities 9 Fall Sports Wrap Ups 22 Joe Gauld Visit 10 Winter Sports 28 Band Love for Schade 11 Trunk or Treat 12 State Conference 13 Food For Thought 32 Semi– Formal 14 Off the Farm 33 Poetry Out Loud 15 Who’z That? 34 Christmas at School 16 10 Best Ways to Help 35 The Harg 17 Musical Preview 17 Wish What? 18 3 NEWS NEWS NEWS NEWS NEWS NEWS NEWS NEWS NEWS NEWS NEWS NEWS NEWS NEWS NEWS NEWS Gratz Fair 2015 Congratulations to Our Gratz Fair Queen! 4 NEWS NEWS NEWS NEWS NEWS NEWS NEWS NEWS NEWS NEWS NEWS NEWS NEWS NEWS NEWS NEWS Mini Thon ini-Thon is an annual event that takes place here at Halifax to help raise money for the Four Diamonds M Fund. This year Mini-Thon took place right after homecoming, on October 9th. Over half the school joined together to have a great night while raising both money and awareness for childhood cancer. -

LIONS GATE ENTERTAINMENT CORP. (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

Table of Contents UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 Form 10-K (Mark One) ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended March 31, 2012 or TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from to Commission File No.: 1-14880 LIONS GATE ENTERTAINMENT CORP. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) British Columbia, Canada N/A (State or Other Jurisdiction of (I.R.S. Employer Incorporation or Organization) Identification No.) 1055 West Hastings Street, Suite 2200 2700 Colorado Avenue, Suite 200 Vancouver, British Columbia V6E 2E9 Santa Monica, California 90404 (877) 848-3866 (310) 449-9200 (Address of Principal Executive Offices, Zip Code) Registrant’s telephone number, including area code: (877) 848-3866 Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of Each Class Name of Each Exchange on Which Registered Common Shares, without par value New York Stock Exchange Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None ___________________________________________________________ Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes No Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934. Yes No Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. -

Lynn Again Makes a Peaceful Point

DEALS OF THE $DAY$ PG. 3 SATURDAY, JUNE 6, 2020 DEALS Two messages OF THE $DAY$ delivered PG. 3 in Salem DEALS By David McLellan ITEM STAFF OF THE SALEM — A couple hundred protesters out- $DAY$ side the Salem Police headquarters Friday night PG. 3 called for an end to racial violence and police brutality in the U.S. But many of them had an- other request — that Salem Police Capt. Kate Stephens lose her job. Stephens was placed on leave after sending out a tweet Tuesday on the Salem Police official DEALS Twitter page that read, “So you issued a permit for 10 of thousands of people to protest but I OF THE can’t go to a restaurant? You are ridiculous. You $ $ and Too Tall Deval are killing this state.” DAY Stephens’ tweet was in regards to Boston Mayor PG. 3 Marty Walsh and Gov. Charlie Baker’s handling ITEM PHOTO | SPENSER HASAK SALEM, A2 Anthony Coleman of Lynn chants “Black Lives Matter” as he marches through Lynn with WOMAN ARRESTED fellow protesters rallying against police brutality and racism. DEALS OF THE IN PEABODY PROTEST Lynn again makes a peaceful $pointDAY$ By Anne Marie Tobin By David McLellan es standing and chanting in the killing ofPG. George 3 Floyd, ITEM STAFF ITEM STAFF protest of racial violence and an unarmed black man who Police police brutality. died after a police officer in PEABODY — Myra Reyes, 64, a resident at the LYNN — Several black and “It’s not a black movement, Minneapolis knelt on his neck Crowninshield Apartment complex, was arrest- estimate Hispanic boys, some not even it’s not a white movement, it’s for more than eight minutes ed and charged with disorderly conduct Friday 13 years old, stood in front of an us movement,” said Raven on May 25. -

Top 1000 Searches in Youtube Australia

Top 1000 Searches in YouTube Australia https://www.iconicfreelancer.com/top-1000-youtube-australia/ # Keyword Volume 1 pewdiepie 580000 2 music 368000 3 asmr 350000 4 pewdiepie vs t series 268000 5 james charles 222000 6 old town road 214000 7 lazarbeam 207000 8 david dobrik 202000 9 billie eilish 197000 10 dantdm 194000 11 norris nuts 190000 12 fortnite 179000 13 bts 176000 14 joe rogan 172000 15 ksi 163000 16 wwe 151000 17 jacksepticeye 147000 18 songs 141000 19 baby shark 132000 20 t series 132000 21 markiplier 131000 22 minecraft 126000 23 nightcore 123000 24 sidemen 116000 25 shane dawson 111000 26 lofi 110000 27 ariana grande 110000 28 ssundee 105000 29 logan paul 101000 30 blackpink 101000 31 amv 99000 32 eminem 97000 33 peppa pig 97000 34 jake paul 96000 35 msnbc 96000 36 taylor swift 95000 37 study music 94000 38 senorita 93000 39 mrbeast 91000 40 crime patrol 2019 90000 41 ufc 89000 42 lachlan 89000 43 trump 88000 44 nba 87000 45 game of thrones 85000 46 ed sheeran 84000 47 sis vs bro 84000 48 jeffree star 80000 49 jre 77000 50 morgz 77000 51 mr beast 75000 52 fgteev 74000 53 cnn 74000 54 stephen colbert 74000 55 post malone 73000 56 flamingo 73000 57 gacha life 72000 58 wiggles 70000 59 try not to laugh 70000 60 unspeakable 69000 61 twice 68000 62 bad guy 68000 63 avengers endgame 67000 64 superwog 67000 65 isaac butterfield 67000 66 memes 66000 67 tati 66000 68 documentary 65000 69 rebecca zamolo 64000 70 f1 64000 71 movies 64000 72 dance monkey 64000 73 popularmmos 63000 74 chad wild clay 62000 75 tfue 61000 76 jelly 61000 -

SAY Igoodbye to Icarly and GET READY for an ALIEN INVASION AS MARVIN MARVIN PREMIERES on NICKELODEON

For immediate release SAY iGOODBYE TO iCARLY AND GET READY FOR AN ALIEN INVASION AS MARVIN MARVIN PREMIERES ON NICKELODEON London – 13th March 2013 – Nickelodeon is set for a bumper hour and a half of programming on Friday 5th April as it premieres the series finale of iCarly followed by the premiere of a brand-new out of this world live-action comedy series, Marvin Marvin. Nickelodeon’s beloved hit comedy iCarly, has entertained millions throughout its five seasons. Since its UK premiere on the 24th March 2008 it has introduced random dancing and spaghetti tacos to popular culture and become one of the most successful shows of its time. Its cult status has been cemented by guest appearances from the fans such as Michelle Obama, Emma Stone, and One Direction. Not only creating household names out of its regular cast, the show has launched the careers of teen talent such as Harry Shum Jnr (‘iGo to Japan,’ Mike Chan Glee), Malese Jow (‘iLook Alike,’ Anna The Vampire Diaries) and Chord Overstreet (‘iSpeed Date,’ Sam Evans Glee). Currently Nickelodeon’s longest running show, its ground-breaking format, that allowed viewers to upload content, not only secured its huge ratings but helped spark a whole new genre of TV. The show will end its four year run with an unforgettable hour-long series finale ‘iGoodbye’ on Nickelodeon at 5.30pm. Viewers will see the first appearance of Carly Shay’s Air Force father Colonel Shay, played by David Chisum, in an emotional culmination of the much loved series. “I'm insanely proud to have created a TV show that's loved by so many people around the world, and I'm thrilled to have had the opportunity to work with this remarkably talented cast for the past five years,” said Dan Schneider, iCarly Creator and Executive Producer.