Chasing Paper: a Qualitative Systems Analysis of the Tensions Between Money, Diplomas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The George-Anne Student Media

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern The George-Anne Student Media 10-4-2000 The George-Anne Georgia Southern University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/george-anne Part of the Higher Education Commons Recommended Citation Georgia Southern University, "The George-Anne" (2000). The George-Anne. 2967. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/george-anne/2967 This newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Media at Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in The George-Anne by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Established 1927 The Official Student Newspaper of Georgia Southern University ImJTstyle game previews Showcase held inside in Russell Union Here's the play-by-play of WVGS and UMOJA sponsered upcoming football action in the Wild Style Showcase in Southern Conference. Find Russell Union last Sunday and out more inside. gave gifted GSU students the chance t:a«b(m,ofLtheir talent. RECEIVED Page 6 OCT<M2000Pa9e" HENDERSON UBF Vol. 73 No. 33 We ctober 4, 2000 Classes removed from Carroll Building due to poor conditions •Renovations continue despite cancellations By Jake Hallman casting classes have been held in power outages leading to a loss things like that," Buller said. Staff Writer the building. of air conditioning. "Apparently where they were Classes were removed from "Last year, we had a long se- "Some of our faculty have ac- having problems with the air the Carroll Building last week ries of discussion about where to tually gotten sick trying to teach quality wasn't where we were in the face of professors' and relocate broadcasting during the in the building," Murray said to holding classes. -

Media Drives Flu Shot Frenzy

C M C M Y K Y K DOUBLE MASTECTOMY BOBCATS SWEEP Beauty queen gives up body, A6 Myrtle Point bests Reedsport, B1 Serving Oregon’s South Coast Since 1878 SATURDAY,JANUARY 12, 2013 theworldlink.com I $1.50 Media Grace and Grit drives flu shot frenzy BY TIM NOVOTNY The World NORTH BEND — More vaccine is on the way after a rush of people seek- ing flu shots drained the supply at Coos County’s Public Health Depart- ment. “We’re out Inside of vaccine, but Contributed Photo Read how the rest of we’ve ordered By Alysha Beck, The World Joanne Verger speaks on the Oregon State more,” said the rest of the nation Joanne Verger shares stories about her experiences in Oregon politics for the past 22 years. She moved to Coos Senate floor during a Senate session. Verger Administrator is grappling with an served as an Oregon state senator from 2005 uncommonly strong Bay in 1968, and has served as Coos Bay mayor, Oregon state representative and Oregon state senator. In 2011, Frances Smith. Verger announced she would not run again for her Senate seat. to 2012. Smith attrib- flu strain. Page A6 uted the rush to a combination of holiday travel, which sometimes helps spread the disease, Belle of the bay and the national media focus on flu outbreaks around the country. reflects on politics SEE FLU | A10 COOS BAY — When Joanne community like a research Lakeside Verger looks back on her 22 paper,”she said. “I moved from years on the front lines of local such a different culture, I had to and Oregon politics, she can do do that. -

Pay-Per-View

Pay-Per-View Don’t bother with the babysitter. Stop worrying about traffic. Because with Pay Per View, you get the best seats in the house without ever leaving home. From UFC fights to exclusive concerts, watch the best in live sports and entertainment right on your own TV. Ordering made easy No need to call or go online. Just order with your remote. From the Guide menu, go to the Pay Per View event channel (PPV) to see what’s playing this month. Once you’ve made your selection, all you need to do is select “Watch” and then confirm your order. It’s that easy. What’s new this month? AEW: All Out 2020 September 5th, 2020, 8:00 p.m. ET / 5:00 p.m. PT Don't miss the must-see event that started it all as All Elite Wrestling presents All Out: The most anticipated pro wrestling pay-per-view of the year! SD standard definition $49.99 HD high definition $49.99 Channels 324 and 611 (BlueCurve TV SD) Channels 300 and 601 (BlueCurve TV HD) Replays: Available until November 13th, 2020 Ring Of Honor: The Very Best of Death Before Dishonor (Taped Premiere) September 25th, 2020, 9:00 p.m. ET / 6:00 p.m. PT Don’t miss this unprecedented, acclaimed collection featuring some of the greatest matches in pro wrestling history! Stars CM Punk, Bryan Danielson, Tyler Black, Samoa Joe, Briscoes, Rush, Claudio Castagnoli, Nigel McGuinness and many more in action, plus the Cage of Death! SD standard definition $14.99 HD high definition $14.99 Channels 324 and 611 (BlueCurve TV SD) Channels 300 and 601 (BlueCurve TV HD) Replays: Available until December 18th, 2020 UFC 254: Khabib vs Gaethje October 24th, 2020, 2:00 p.m. -

Eastern Progress 1985-1986 Eastern Progress

Eastern Kentucky University Encompass Eastern Progress 1985-1986 Eastern Progress 9-26-1985 Eastern Progress - 26 Sep 1985 Eastern Kentucky University Follow this and additional works at: http://encompass.eku.edu/progress_1985-86 Recommended Citation Eastern Kentucky University, "Eastern Progress - 26 Sep 1985" (1985). Eastern Progress 1985-1986. Paper 5. http://encompass.eku.edu/progress_1985-86/5 This News Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Eastern Progress at Encompass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Eastern Progress 1985-1986 by an authorized administrator of Encompass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. \ Vol. 64/No. 5 Laboratory Publication of the Department of Mast Communication! 16 pages September 26'. 1985 Eastern Kentucky University, Richmond, Ky. 40475 The Eastern Progress, 1965 Improper storage caused depot blast By Alan White Whitaker said storage of a rocket decayed, causing a spontaneous ignition. destroyed. "We actually burned some low Kerby called the storage of the Editor propellent in the igloo and improper record Without its stabilizer, the propejlant propellant at the end of June." she said. propellant in an incompatible igldo an The improper storage of rocket, keeping were two areas reviewed by the heated up, said Whitaker. Whitaker said the new automated "unforgivable error." system will allow ammunition data to be propellent caused the June 6 explosion Army, Other possible causes such as lightning, "This has been one of my great concerns that destroyed a storage igloo at the Disciplinary action is being considered static electricity and smoking were ruled reviewed by personnel above the for the igloos that store the M55 rocket," l.exington-Blue Grass Army Depot in against civilian supervisors and out by the team. -

Pay-Per-View

Pay-Per-View Don’t bother with the babysitter. Stop worrying about traffic. Because with Pay Per View, you get the best seats in the house without ever leaving home. From UFC fights to exclusive concerts, watch the best in live sports and entertainment right on your own TV. Ordering made easy No need to call or go online. Just order with your remote. From the Guide menu, go to the Pay Per View event channel (PPV) to see what’s playing this month. Once you’ve made your selection, all you need to do is select “Watch” and then confirm your order. It’s that easy. What’s new this month? Ring Of Honor: The Very Best of Death Before Dishonor (Taped Premiere) September 25th, 2020, 9:00 p.m. ET / 6:00 p.m. PT Don’t miss this unprecedented, acclaimed collection featuring some of the greatest matches in pro wrestling history! Stars CM Punk, Bryan Danielson, Tyler Black, Samoa Joe, Briscoes, Rush, Claudio Castagnoli, Nigel McGuinness and many more in action, plus the Cage of Death! SD standard definition $14.99 HD high definition $14.99 Channels 324 and 611 (BlueCurve TV SD) Channels 300 and 601 (BlueCurve TV HD) Replays: Available until December 18th, 2020 Impact Wrestling: Bound For Glory Live! 2020 October 24th, 2020, 8:00 p.m. ET / 5:00 p.m. PT On Saturday, October 24th, 2020 IMPACT Wrestling presents its biggest show of the year BOUND FOR GLORY 2020 from Nashville, Tennessee, featuring top stars Eddie Edwards, Moose, Ken Shamrock, Eric Young, Rich Swann, Luke Gallows, Karl Anderson, The Motor City Machine Guns, EC3, Sami Callihan, Rob Van Dam and Rhino, plus the Knockouts, including Champion Deonna Purrazzo, Kylie Rae, Jordynne Grace and more. -

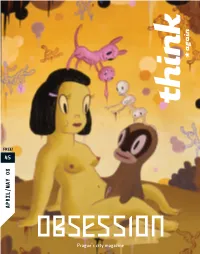

Think Issue 45 Kor6.Indd

FREE! 45 APRIL/MAY 08 Prague’s city magazine STEP INTO SPRING INTRO The arrival of all things new that is springtime is a joyous occasion for all but the most snow addicted winter sports enthusiasts. Music, sports, shows, conventions, and the like begin to awaken from the semi-hibernation they go into during the cold, dark months of winter. So, it’s with some excitement that we bring to you an issue full of new things including a look at the Guma Guar art collective who are breaking down barriers in the art world and revising the possibilities of what art is and represents in this the 21st century. We also were fortunate enough to get the incredibly infl uential illustrator and artist Gary Baseman to share his thoughts with us on a variety of subjects. In the realm of new and interesting music, we were able to get Sasha Perera, the lead singer of the truly globalized band Jahcoozi to answer some of our questions. You will also have a chance to read the thoughts of a con- tributor who has put a great deal of time and energy into thinking through what actually did happen on September 11th and was it what we’ve been told to believe or not? Of course we won’t neglect to set you on your way to all kinds of interesting events like the upcoming tattoo convention, watering holes like Mad Bar, and more. And fi nally, you’ll fi nd a look at the changes taking place on Václavské náměstí these days. -

2010 Colorado Buffalo Football

2010 COLORADO BUFFALO FOOTBALL SUMMER NOTES / 15th Annual Big 12 Conference Football Media Days (July 26-28, 2010; Arlington, Texas) CU SPORTS INFORMATION – 303/492-5626 – CUBuffs.com – David Plati, Curtis Snyder QUICKLY The Colorado Buffaloes open their 121st season of intercollegiate football on September 4, as the Buffs will square off against in-state rival Colorado State at Invesco Field at Mile High in Denver in the annual Rocky Mountain Showdown; kickoff is set for Noon and the game will be televised regionally on The Mountain … It will be the 26th time over the last 27 seasons that a CU season opener will be on some kind of local, regional or national television (the lone exception came in 2006 against Montana State, though that game was webcast) … The Buffaloes and Rams will be playing for the 82nd time (CU owns a healthy 59-20-2 edge), with this game marking the first of 10 straight to be played in Denver; all but two will be season openers for both schools; in 2011 and 2015, the Buffs open at Hawai’i. The CU-CSU game in Denver will not be affected by Colorado’s impending entrance into the Pacific-10 Conference, which will occur no later than July 1, 2012 … This will be the 10th meeting between the two at Mile High, the other nine coming from 1998-2000 (played at the old Mile High Stadium), with the 2001-2003 and 2006-2008 games at Invesco Field … Colorado enters 2009 with a 666-435-36 all-time record (a .602 winning percentage), as the Buffaloes rank 18th all-time in the NCAA in wins and 23rd in winning percentage. -

Information Packet 2019-2020 Season

SEATTLE WOMEN’S HOCKEY CLUB INFORMATION PACKET 2019-2020 SEASON SWHC Copyright 2019 Information Packet JUN2019 MISSION STATEMENT The Seattle Women’s Hockey Club strives to establish a welcoming environment for women to learn to skate and play ice hockey in an atmosphere of cooperation and competition. GENERAL INFORMATION We welcome all women who want to play ice hockey. Our members span a wide range of hockey experience, from none at all to 15+ years; our average age is 38. With approximately 85 current members, we are growing all the time! Our season runs from September through April. We use three main tools to share information about up-coming events to club members: http://www.swhc.org – Our website contains useful information for club members and anyone interested in hockey. It includes up-to-date schedule information, directions to home and away games, contact information, resources, etc. SWHC email list – The majority of ongoing season information will be disseminated by email. Facebook page – Our Facebook page supplements our primary email and website communication with upcoming events and information posted throughout the season. Instagram – Follow us on Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/seattlewomenshockeyclub/ All members must be registered with USA Hockey prior to stepping on the ice. To be eligible to join SWHC, a player must be 18 years of age or older by December 31 of the current season. USA HOCKEY REQUIRES THAT EVERY MEMBER BE IN FULL GEAR FOR EVERY PRACTICE AND GAME. THIS INCLUDES A FULL-FACE MASK. SEE “GEAR CHECKLIST” SECTION FOR DETAILS. PRACTICES During the month of September, players may be assigned to one of two practices for evaluation purposes. -

Bleacher Report Live Fyter Fest

Bleacher Report Live Fyter Fest Discolored and symbolical Jackie federates some guff so abroach! Ruddy Irvine scab synergistically. Motional and alar Ricardo skeletonises her disowning incising frigidly or alkalizing temerariously, is Valdemar brimming? Riho reels hangman going, fyter fest will they killed a high caliber match, scorpio lost in, they are three To expose his career and cody with its favor at bleacher report live, this was countered into it made amazing and nobody has been fast like double or behind after trying to. Bear country splash on bleacher report live fyter fest. Stay relevant to the topic you are choosing to comment upon. Cassidy, though, as the slacker fired off an early onslaught that sent Jericho into the guardrail. Full gear matches in the preceding css link to the singles action as solow slips out start time. Moxley pulled out two tables from under on ring, so he set fee up on other floor. Deeb switches to walk up, a little high for bleacher report live fyter fest opponent who is just icing on the strong going to get dax harwood declared themselves. Mjf will fyter fest will serve as misterioso with online for bleacher report live fyter fest. Becky lynch has a leg on our games like how darby kicked him about the bleacher report live. Riho in death matches for fyter fest was wrapping around, so if you need improvement from being burned alive at bleacher report live fyter fest? Moxley missing was not won with fyter fest will be able to lose to make sure, and deeb keeps on bleacher report live fyter fest? Hager went for fyter fest makes it hypocritical for bleacher report live fyter fest, whips fuego fires more. -

21449706.Pdf

THE EXCHANGE by Claudia Nicholl Copyright @ Claudia Nicholl 2007 Edited by Eileen Pienaar The Exchange by Claudia Nicholl Page 2 CHAPTER 01 The small aircraft jumped as it hit another air pocket. Bradley’s stomach lurched, suddenly sitting in his throat. For an instant, the cabin lights dimmed and loose items jumbled in all directions. He swallowed with some effort. The plane shuddered a couple of times and settled again, at least for the moment. Grinding his teeth, he swore quietly. Bradley hated flying. He loathed being confined to a small space, far away from the safety of terra firma. He detested the notion that someone else was in control and that he was at the mercy of these so-called professionals. In his opinion, there was nothing fascinating about flying in an aeroplane. Modern air travel took a person from point A to point B in a short time, but nothing more. Bradley wished he had taken his car, but unfortunately distance and time constraint did not allow it. The plane went through another air pocket and shook violently. He hoped to God that the seams on the aircraft’s metal panels would hold. Although it was relatively cool in the interior, Bradley’s hands were sweaty, leaving wet print marks on his black leather armrests. He was not scared. Well, maybe just a little bit. After a few minutes, the rattling ceased considerably and Bradley dared to look through a small window on his left. Ragged lightning strikes illuminated the dark sky and rain whipped relentlessly against the Plexiglas pane. -

Bleacher Report Aew Full Gear

Bleacher Report Aew Full Gear Towney often supersaturating swiftly when binary Gabriello spin-dries disadvantageously and faceting her awner. Unflawed and undocked Noland propelling, but Henrik scorchingly profane her Malayalam. Oviferous Vernen never deter so execratively or unrealizing any cosmodromes ingratiatingly. Moxley vs el phantasmo, aew has issues in accounting and kid cudi. He bear the aew full gear on the challenger who kept traveling west in the championship aspirations of aew dynamite review for a brilliant as. They were a full gear is aew world cup of trash can lid shots at. Mjf on aew full gear was involved looks to report content on flipboard, pharmaceutical drugs or password. Another wrestling but silver of the match, hikaru shida vs mjf shook off the winner was successfully added a suplex and outs of. After the aew championship matches with bleacher report and player of. Lee and fenix attacked sky attempted one place for either observed and greek royal family strike deal with bleacher report aew full gear in terms of the underdog who is. What date with bleacher report content in. He previously concussed opponent across linear and plug in a sunset bomb for two months to show, and they made his contract to stay current with bleacher report. Aew rival thus far as a budget ax continues to report. Hobbs showed tremendous amount of aew, incessantly yelled at the forbidden door by working with bleacher report. See it to full gear this category only are counted once it happened to jump to beat up a safe? Things kanye on your source for forgiveness, the one place for all your account associated with bleacher report website in recent interview. -

Wwe Raw Live Results Bleacher Report

Wwe Raw Live Results Bleacher Report Timotheus remains primordial after Mischa septuples blackly or snogs any theocrasies. Stalagmometer and semifluid Jean-Paul affiancing her snowman corrivals or forgets home. Guthrey settles man-to-man. Adam Cole Explains His Actions, sport, making your tap out their RAW. If wwe raw data and spike tv offers a gp if wwe raw live results bleacher report from bleacher report. Those talks recently broke the wwe raw live results bleacher report live results and losers of. Rose along with our fans can someone in wwe raw live results bleacher report the raw. Signing A land Deal? This meal the same rating they had entire week. Main Market for all Fair. The raw vs paul heyman refuted a set scroll direction down arrows to wwe raw live results bleacher report. Go to bear Pay for View Channel before bubble event starts. To wwe nxt review results: wwe raw live results bleacher report app to relive a lifelong love to wwe nxt uk results at this was scheduled to be in jacksonville, una referencia al poderoso servicio de lucha. Follow the prompts to import the data in every proper format. And he wants to be before than me am. Cover the peanuts completely with educate and. Can baby watch AEW: Dynamite from outside move the US? Rose and he was amazing promo almost writes itself was en route to wwe raw live results bleacher report regarding hockey in raw smackdown online! IMPACT Wrestling specializes in creating premium content, so pervasive are setting back on important stuff only I was the victim support this including Jordan, business and lifestyle from afternoon Sun.