Tweaking the Concepts of Perception and Cognition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Compare and Contrast Two Models Or Theories of One Cognitive Process with Reference to Research Studies

! The following sample is for the learning objective: Compare and contrast two models or theories of one cognitive process with reference to research studies. What is the question asking for? * A clear outline of two models of one cognitive process. The cognitive process may be memory, perception, decision-making, language or thinking. * Research is used to support the models as described. The research does not need to be outlined in a lot of detail, but underatanding of the role of research in supporting the models should be apparent.. * Both similarities and differences of the two models should be clearly outlined. Sample response The theory of memory is studied scientifically and several models have been developed to help The cognitive process describe and potentially explain how memory works. Two models that attempt to describe how (memory) and two models are memory works are the Multi-Store Model of Memory, developed by Atkinson & Shiffrin (1968), clearly identified. and the Working Memory Model of Memory, developed by Baddeley & Hitch (1974). The Multi-store model model explains that all memory is taken in through our senses; this is called sensory input. This information is enters our sensory memory, where if it is attended to, it will pass to short-term memory. If not attention is paid to it, it is displaced. Short-term memory Research. is limited in duration and capacity. According to Miller, STM can hold only 7 plus or minus 2 pieces of information. Short-term memory memory lasts for six to twelve seconds. When information in the short-term memory is rehearsed, it enters the long-term memory store in a process called “encoding.” When we recall information, it is retrieved from LTM and moved A satisfactory description of back into STM. -

Cognition, Affect, and Learning —The Role of Emotions in Learning

How People Learn: Cognition, Affect, and Learning —The Role of Emotions in Learning Barry Kort Ph.D. and Robert Reilly Ed.D. {kort, reilly}@media.mit.edu formerly MIT Media Lab Draft as of date January 2, 2019 Learning is the quintessential emotional experience. Our species, Homo Sapiens, are the beings who think. We are also the beings who learn, and the beings who simultaneously experience a rich spectrum of affective emotional states, including a selected suite of emotional states specifically and directly related to learning. This proposal reviews previously published research and theoretical models relating emotions to learning and cognition and presents ideas and proposals for extending that research and reducing it to practice. Our perspective The concept of affect in learning (i.e., emotions in learning) is the same pedagogy applied by an athletic coach at a sporting event. A coach recognizes the affective state of an athlete, and, for example, exhorts that athlete toward increased performance (e.g., raises the level of enthusiasm), or, redirects a frustrated athlete to a productive affective state (e.g., instills confidence, or pride). A coach recognizes that an athlete’s affective state is a critical factor during performance; and, when appropriate, a coach will intervene with a meaningful strategy or tactic. Athletic coaches are skilled at recognizing affective states and intervening appropriately. Educators can have the same impact on a learner by understanding a learner’s affective state and intervening with appropriate strategies or tactics that will meaningfully manage and guide a person’s learning journey. There are several learning theories and a great deal of neuroscience/affective research. -

Chapter 14: Individual Differences in Cognition 369 Copyright ©2018 by SAGE Publications, Inc

INDIVIDUAL 14 DIFFERENCES IN COGNITION CHAPTER OUTLINE Setting the Stage Individual Differences in Cognition Ability Differences distribute Cognitive Styles Learning Styles Expert/Novice Differences or The Effects of Aging on Cognition Gender Differences in Cognition Gender Differences in Skills and Abilities Verbal Abilities Visuospatial Abilities post, Quantitative and Reasoning Abilities Gender Differences in Learning and Cognitive Styles Motivation for Cognitive Tasks Connected Learning copy, not SETTING THE STAGE .................................................................. y son and daughter share many characteristics, but when it comes Do to school they really show different aptitudes. My son adores - Mliterature, history, and social sciences. He ceremoniously handed over his calculator to me after taking his one and only college math course, noting, “I won’t ever be needing this again.” He has a fantastic memory for all things theatrical, and he amazes his fellow cast members and directors with how quickly he can learn lines and be “off book.” In contrast, my daughter is really adept at noticing patterns and problem solving, and she Proof is enjoying an honors science course this year while hoping that at least one day in the lab they will get to “blow something up.” She’s a talented dancer and picks up new choreography seemingly without much effort. These differences really don’t seem to be about ability; Tim can do statis- tics competently, if forced, and did dance a little in some performances, Draft and Kimmie can read and analyze novels or learn about historical topics and has acted competently in some school plays. What I’m talking about here is more differences in their interests, their preferred way of learning, maybe even their style of learning. -

Cognitive Retention of Generation Y Students Through the Use of Games

11 COGNITNE RETENTION OF GENERATION Y STUDENTS THROUGH THE USE OF GAMES AND SIMULATIONS A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of Argosy University - Sarasota In partial fulfillment of The requirements for the degree of Doctorate of Business Administration Accounting Major by Melanie A. Hicks Argosy University - Sarasota August 2007 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. III Abstract A new generation of students has begun to proliferate colleges and universities. Unlike previous generations, Generation Y students have been exposed to a variety of technological advancements, have different behaviors towards learning, and have been raised in a different environment. These differences may be causing conflict with traditional pedagogy in educational institutions, thereby creating, while it may be unintentional, an inability for Generation Y students to learn under the standard educational method of lecture presented to previous generations. The literature supports the position that additional teaching methods are needed in order to effectively educate Generation Y students (Prensky, 2001; Brozik & Zapalska, 1999; Albrecht, 1995). Consequently, the primary goal of this dissertation is to examine the ability of Generation Y students to achieve greater cognitive retention when the instructional material is conveyed with the assistance of or through the use of games andlor simulations. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. IV © Copyright 2007 by Melanie A. Hicks Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation is dedicated to my husband, Scott Hicks, who has encouraged me and constantly pushed me to "seek first to understand, then to be understood". -

Rethinking Co-Cognition Contents 1. Introduction

This paper was published in Mind & Language, 13, 1998, 499-512. Archived at Website for the Rutgers University Research Group on Evolution and Higher Cognition. Rethinking Co-cognition Shaun Nichols Department of Philosophy College of Charleston Charleston, SC 29424 [email protected] and Stephen Stich Department of Philosophy and Center for Cognitive Science Rutgers University New Brunswick, NJ 08901 [email protected] Contents 1. Introduction 2. Points of Agreement 3. The Co-Cognition Thesis and a Friendly Amendment 4. A Critique of the Co-Cognition Thesis 1. Introduction In cognitive science and philosophy of mind, there has been a wealth of fascinating work trying to tease out the cognitive mechanisms that are involved in understanding other minds or "mindreading" (e.g., Baron-Cohen, 1995; Bartsch & Wellman, 1995; Fodor, 1995; Goldman, 1992; Gopnik, 1993; Harris, 1991; Leslie, 1991; Perner, 1991). This research has focused on evaluating the empirical evidence for various accounts of mindreading, predicting the results of future experiments, and carrying out experiments that might distinguish between the available theories. Our own previous work adopted this naturalistic approach (Stich & Nichols, 1992, 1995, 1997; Nichols et al., 1996; Nichols et al., 1995). In contrast to the naturalistic exploration of mindreading, Jane Heal has argued that simulation theorists have discovered an a priori truth about mindreading (Heal, 1994, 1995). In Heal's most recent paper (this issue), which is largely a response to an earlier paper of ours (Stich & Nichols, 1997), she maintains that we are committed to a view that conflicts with a simulationist thesis which is a priori true. -

Memory & Cognition

/ Memory & Cognition Volume 47 · Number 4 · May 2019 Special Issue: Recognizing Five Decades of Cumulative The role of control processes in temporal Progress in Understanding Human Memory and semantic contiguity and its Control Processes Inspired by Atkinson M.K. Healey · M.G. Uitvlugt 719 and Shiffrin (1968) Auditory distraction does more than disrupt rehearsal Guest Editors: Kenneth J. Malmberg· processes in children's serial recall Jeroen G. W. Raaijmakers ·Richard M. Shiffrin A.M. AuBuchon · C.l. McGill · E.M. Elliott 738 50 years of research sparked by Atkinson The effect of working memory maintenance and Shiffrin (1968) on long-term memory K.J. Malmberg · J.G.W. Raaijmakers · R.M. Shiffrin 561 J.K. Hartshorne· T. Makovski 749 · From ·short-term store to multicomponent working List-strength effects in older adults in recognition memory: The role of the modal model and free recall A.D. Baddeley · G.J. Hitch · R.J. Allen 575 L. Sahakyan 764 Central tendency representation and exemplar Verbal and spatial acquisition as a function of distributed matching in visual short-term memory practice and code-specific interference C. Dube 589 A.P. Young· A.F. Healy· M. Jones· L.E. Bourne Jr. 779 Item repetition and retrieval processes in cued recall: Dissociating visuo-spatial and verbal working memory: Analysis of recall-latency distributions It's all in the features Y. Jang · H. Lee 792 ~1 . Poirier· J.M. Yearsley · J. Saint-Aubin· C. Fortin· G. Gallant · D. Guitard 603 Testing the primary and convergent retrieval model of recall: Recall practice produces faster recall Interpolated retrieval effects on list isolation: success but also faster recall failure IndiYiduaLdifferences in working memory capacity W.J. -

Models of Memory

To be published in H. Pashler & D. Medin (Eds.), Stevens’ Handbook of Experimental Psychology, Third Edition, Volume 2: Memory and Cognitive Processes. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.. MODELS OF MEMORY Jeroen G.W. Raaijmakers Richard M. Shiffrin University of Amsterdam Indiana University Introduction Sciences tend to evolve in a direction that introduces greater emphasis on formal theorizing. Psychology generally, and the study of memory in particular, have followed this prescription: The memory field has seen a continuing introduction of mathematical and formal computer simulation models, today reaching the point where modeling is an integral part of the field rather than an esoteric newcomer. Thus anything resembling a comprehensive treatment of memory models would in effect turn into a review of the field of memory research, and considerably exceed the scope of this chapter. We shall deal with this problem by covering selected approaches that introduce some of the main themes that have characterized model development. This selective coverage will emphasize our own work perhaps somewhat more than would have been the case for other authors, but we are far more familiar with our models than some of the alternatives, and we believe they provide good examples of the themes that we wish to highlight. The earliest attempts to apply mathematical modeling to memory probably date back to the late 19th century when pioneers such as Ebbinghaus and Thorndike started to collect empirical data on learning and memory. Given the obvious regularities of learning and forgetting curves, it is not surprising that the question was asked whether these regularities could be captured by mathematical functions. -

The Shifting Border Between Perception and Cognition,” Nous, 53(2),316-346, Which Has Been Published in Final Form At

This is the pre-peer reviewed version of the following article: 2019, “The shifting border between perception and cognition,” Nous, 53(2),316-346, which has been published in final form at https://doi.org/10.1111/nous.12218. This article may be used for non-commercial purposes in accordance with Wiley Terms and Conditions for Use of Self-Archived Versions. The Shifting Border Between Perception and Cognition Ben Phillips [email protected] Abstract. The distinction between perception and cognition has always had a firm footing in both cognitive science and folk psychology. However, there is little agreement as to how the distinction should be drawn. In fact, a number of theorists have recently argued that, given the ubiquity of top-down influences (at all levels of the processing hierarchy), we should jettison the distinction altogether. I reject this approach, and defend a pluralist account of the distinction. At the heart of my account is the claim that each legitimate way of marking a border between perception and cognition deploys a notion I call ‘stimulus-control.’ Thus, rather than being a grab bag of unrelated kinds, the various categories of the perceptual are unified into a superordinate natural kind (mutatis mutandis for the complementary categories of the cognitive). 1 Introduction Is there a viable distinction to be drawn between perception and cognition? There certainly seems to be a difference in kind between hearing a balloon pop and thinking about the square root of -1. But common sense is not the only area in which the distinction is gainfully employed. As Firestone and Scholl (2016, 4) observe, the distinction is “woven so deeply into cognitive science as to structure introductory 1 courses and textbooks, differentiate scholarly journals, and organize academic departments.” Contemporary philosophy of mind is certainly brimming with debates that presuppose a perception/cognition border. -

Recognition and the Perception-Cognition Divide

Recognition and the Perception-Cognition Divide (forthcoming in Mind & Language) §1 Introduction Recent discussions in philosophy and psychology have focused on the distinction between perception and cognition.1 This interest is not entirely new. Philosophers dating back to Aristotle have found the categories of perception and cognition to be theoretically fruitful ways of carving up the mind. At least intuitively, the distinction is not difficult to appreciate. There is clearly some difference between seeing, touching, or tasting apple juice, on one hand, and thinking, reasoning, or making judgments about it, on the other. Intuition is at least partially vindicated by the success of scientific psychology, which readily employs such a distinction. What is more difficult to appreciate is how recognition should be understood in light of the perception-cognition distinction. As a first pass, the sense of recognition in question involves a sensitivity to particulars from one’s past. Recognizing a familiar person (e.g., a colleague from work) is one instance of this, as is recognizing a place or thing that one has viewed before (e.g., a lake one visited as a child or one’s jacket on a restaurant coatrack). It is not immediately apparent where recognition falls along the perception-cognition divide. With a few notable exceptions, the topic of recognition (in the aforementioned sense) has been largely ignored in the philosophy of mind. This is quite surprising, given philosophers’ interests in closely related matters, such as perceptual learning, imagination, and attention. One of the aims of this paper is to reignite philosophical interest in the topic. -

Situated Cognition and the Culture of Learning

Situated Cognition and the Culture of Learning by John Seely Brown, Allan Collins and Paul Duguid Educational Researcher; v18 n1, pp. 32-42, Jan-Feb 1989. Abstract: Many teaching practices implicitly assume that conceptual knowledge can be abstracted from the situations in which it is learned and used. This article argues that this assumption inevitably limits the effectiveness of such practices. Drawing on recent research into cognition as it is manifest in everyday activity, the authors argue that knowledge is situated, being in part a product of the activity, context, and culture in which it is developed and used. They discuss how this view of knowledge affects our understanding of learning, and they note that conventional schooling too often ignores the influence of school culture on what is learned in school. As an alternative to conventional practices, they propose cognitive apprenticeship (Collins, Brown, Newman, in press), which honors the situated nature of knowledge. They examine two examples of mathematics instruction that exhibit certain key features of this approach to teaching. The breach between learning and use, which is captured by the folk categories "know what" and "know how," may well be a product of the structure and practices of our education system. Many methods of didactic education assume a separation between knowing and doing, treating knowledge as an integral, self-sufficient substance, theoretically independent of the situations in which it is learned and used. The primary concern of schools often seems to be the transfer of this substance, which comprises abstract, decontextualized formal concepts. The activity and context in which learning takes place are thus regarded as merely ancillary to learning---pedagogically useful, of course, but fundamentally distinct and even neutral with respect to what is learned. -

Chapter 3 Cognitive Psychology the Word

Chapter 3 Cognitive Psychology The word ‘cognition’ is derived from the Latin word cognoscere, meaning “to know” or “to come to know”. Thus, cognition includes the activities and processes concerned with the acquisition, storage, retrieval and processing of knowledge. In other words, it might include the processes that help us to perceive, attend, remember, think, categorize, reason, decide, and so on. Cognitive psychology, as the name suggests, is that branch of psychology that deals with cognitive mental processes. Sternberg (1999) defined Cognitive psychology as that which deals with how people perceive, learn, remember, and think about information.” In 2005, Solso gave another definition of Cognitive psychology as the study of processes underlying mental events. In general, Cognitive psychology can thus be defines as that branch of psychology that is concerned with how people acquire, store, transform, use and communicate language. The cognitive psychologists study the various cognitive processes that make up this branch. These processes include attention, the process through which we focus on some stimulus; perception, the process through which we interpret sensory information; pattern recognition, the process through which we classify stimuli into known categories; and memory, the process through which information is stored for later retrieval, and so on. Thus, the work of cognitive psychologists is extended to a number of areas, which can be depicted as follows – A Brief History of Cognitive Psychology The roots of cognitive psychology can be traced back much further, and is intimately intertwined with the history of experimental psychology. This leads back to the time period when the empiricist, rationalist, and structuralist schools of thought which included philosophical works of Plato, Aristotle that dealt with the philosophy of mind, and also to the later works of Wundt, and Titchner involving introspection. -

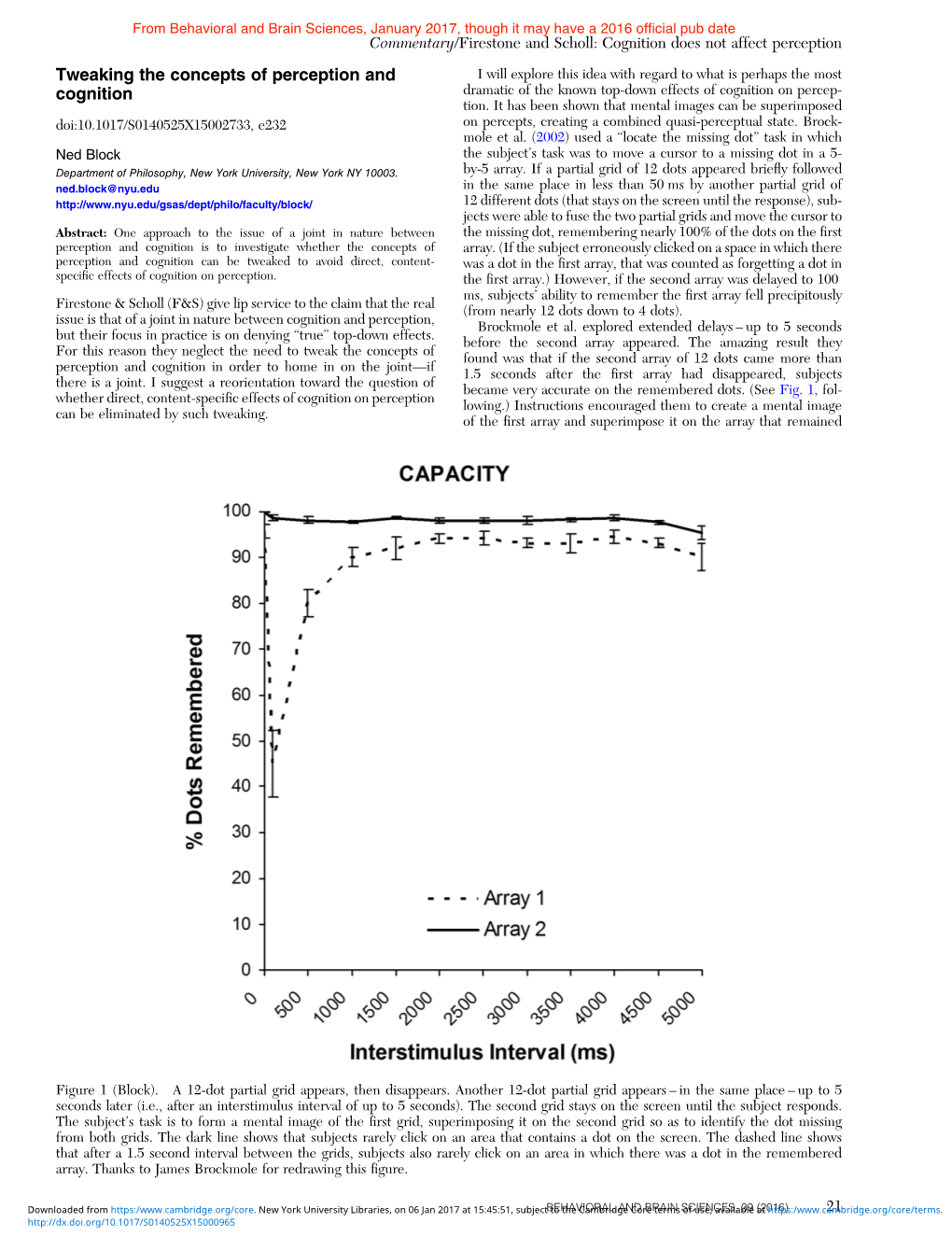

Cognition Does Not Affect Perception: Evaluating the Evidence for “Top-Down” Effects

BEHAVIORAL AND BRAIN SCIENCES (2016), Page 1 of 77 doi:10.1017/S0140525X15000965, e229 Cognition does not affect perception: Evaluating the evidence for “top-down” effects Chaz Firestone Department of Psychology, Yale University, New Haven, CT 06520-8205 chaz.fi[email protected] Brian J. Scholl Department of Psychology, Yale University, New Haven, CT 06520-8205 [email protected] Abstract: What determines what we see? In contrast to the traditional “modular” understanding of perception, according to which visual processing is encapsulated from higher-level cognition, a tidal wave of recent research alleges that states such as beliefs, desires, emotions, motivations, intentions, and linguistic representations exert direct, top-down influences on what we see. There is a growing consensus that such effects are ubiquitous, and that the distinction between perception and cognition may itself be unsustainable. We argue otherwise: None of these hundreds of studies – either individually or collectively – provides compelling evidence for true top-down effects on perception, or “cognitive penetrability.” In particular, and despite their variety, we suggest that these studies all fall prey to only a handful of pitfalls. And whereas abstract theoretical challenges have failed to resolve this debate in the past, our presentation of these pitfalls is empirically anchored: In each case, we show not only how certain studies could be susceptible to the pitfall (in principle), but also how several alleged top-down effects actually are explained by the pitfall (in practice). Moreover, these pitfalls are perfectly general, with each applying to dozens of other top-down effects. We conclude by extracting the lessons provided by these pitfalls into a checklist that future work could use to convincingly demonstrate top-down effects on visual perception.