Pixar's New Fairy Tale Brave: a Feminist Redefinition of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Signal-1961-02-10.Pdf

Van Vess Goes via Fulbright Destination: Thailand Professor Roy W. VanNess, Associate Professor of Physical Edu cation at Trenton State College, is the recipient of a United States Educational Exchange Grant to the College of Physical Education at tate Bangkok, Th ailand for the academic year of 1961-62. The Department of State announces this award made under the orovisions of the Fulbright Act as Jne of more than five hundred ,,-ants fo r lecturing and research abroad. The purpose of awarding ignal this grant to Professor VanNess is to f acilitate lectures in physical education and athletics. Vol. LXXV, No. 13 Trenton State College Friday, February 10, 1961 In 1955, h e was awarded a sim S ilar exchange grant to Bagdad, Iraq, in the Middle East where he helped to start a physical educa HOLD OUTDOOR GRADUATION tion college. I oo E-tonj- CEREMONY PLANNED JUNE 5 The Senior Class President, Charles Good, has announced the Graduation Committee's acceptance of LAOS the June 5, 1961 commencement exercises outdoors on the lawn behind the Allen House Unit. Recommendations by the Senior Class were presented to Dr. Crowell, chairman of the faculty com mittee, and in turn discussed and approved at a meeting of the chairmen of departments held on Wed nesday afternoon, January 25, _ 1961. This committee also an President Martin has announced dition, special attention will be nounces an early Awards Assem to the faculty: "In order that given to junior class representa bly to be held on Wednesday after grades for seniors may be recorded tives so as to acquaint them with noon, May 24. -

Joy Harjo Reads from 'Crazy Brave' at the Central Library

Joy Harjo Reads From 'Crazy Brave' at the Central Library [0:00:05] Podcast Announcer: Welcome to the Seattle Public Library's podcasts of author readings and Library events; a series of readings, performances, lectures and discussions. Library podcasts are brought to you by the Seattle Public Library and Foundation. To learn more about our programs and podcasts visit our website at www.spl.org. To learn how you can help the Library Foundation support the Seattle Public Library go to foundation.spl.org. [0:00:40] Marion Scichilone: Thank you for joining us for an evening with Joy Harjo who is here with her new book Crazy Brave. Thank you to Elliot Bay Book Company for inviting us to co-present this event, to the Seattle Times for generous promotional support for library programs. We thank our authors series sponsor Gary Kunis. Now, I'm going to turn the podium over to Karen Maeda Allman from Elliott Bay Book Company to introduce our special guest. Thank you. [0:01:22] Karen Maeda Allman: Thanks Marion. And thank you all for coming this evening. I know this is one of the readings I've most look forward to this summer. And as I know many of you and I know that many of you have been reading Joy Harjo's poetry for many many years. And, so is exciting to finally, not only get to hear her read, but also to hear her play her music. Joy Harjo is of Muscogee Creek and also a Cherokee descent. And she is a graduate of the Iowa Writers Workshop at the University of Iowa. -

MUSIC and MOVEMENT in PIXAR: the TSU's AS an ANALYTICAL RESOURCE

Revis ta de Comunicación Vivat Academia ISSN: 1575-2844 Septiembre 2016 Año XIX Nº 136 pp 82-94 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15178/va.2016.136.82-94 INVESTIGACIÓN/RESEARCH Recibido: 18/12/2015 --- Aceptado: 27/05/2016 --- Publicado: 15/09/2016 Recibido: 18/12/2015 --- Aceptado: 27/05/2016 --- Publicado: 15/09/2016 MUSIC AND MOVEMENT IN PIXAR: THE TSU’s AS AN ANALYTICAL RESOURCE Diego Calderón Garrido1: University of Barcelona. Spain [email protected] Josep Gustems Carncier: University of Barcelona. Spain [email protected] Jaume Duran Castells: University of Barcelona. Spain [email protected] ABSTRACT The music for the animation cinema is closely linked with the characters’ movement and the narrative action. This paper presents the Temporary Semiotic Units (TSU’s) proposed by Delalande, as a multimodal tool for the music analysis of the actions in cartoons, following the tradition of the Mickey Mousing. For this, a profile with the applicability of the nineteen TSU’s was applied to the fourteen Pixar movies produced between 1995-2013. The results allow us to state the convenience of the use of the TSU’s for the music comprehension in these films, especially in regard to the subject matter and the characterization of the characters and as a support to the visual narrative of this genre. KEY WORDS Animation cinema, Music – Pixar - Temporary Semiotic Units - Mickey Mousing - Audiovisual Narrative – Multimodality 1 Diego Calderón Garrido: Doctor in History of Art, titled superior in Modern Music and Jazz music teacher and sound in the degree of Audiovisual Communication at the University of Barcelona. -

Brave Waiting No

Sermon #1371 Metropolitan Tabernacle Pulpit 1 BRAVE WAITING NO. 1371 A SERMON DELIVERED ON LORDS-DAY MORNING, AUGUST 26, 1877, BY C. H. SPURGEON, AT THE METROPOLITAN TABERNACLE, NEWINGTON. “Wait on the Lord: be of good courage and He shall strengthen your heart: wait, I say, on the Lord.” Psalm 27:14. THE Christian’s life is no child’s play. All who have gone on pilgrimage to the celestial city have found a rough road, sloughs of despond and hills of difficulty, giants to fight and tempters to shun. Hence there are two perils to which Christians are exposed—the one is that under heavy pressure they should start away from the path which they ought to pursue—the other is lest they should grow fearful of failure and so become faint-hearted in their holy course. Both these dangers had evidently occurred to David and in the text he is led by the Holy Spirit to speak about them. “Do not,” he seems to say, “do not think that you are mistaken in keeping to the way of faith. Do not turn aside to crooked policy. Do not begin to trust in an arm of flesh, but wait upon the Lord.” And, as if this were a duty in which we are doubly apt to fail, he repeats the exhortation and makes it more emphatic the second time, “Wait, I say, on the Lord.” Hold on with your faith in God. Persevere in walking according to His will. Let nothing seduce you from your integrity—let it never be said of you, “You ran well, what did hinder you that you did not obey the truth?” And lest we should be faint in our minds, which was the second danger, the psalmist says, “Be of good courage, and He shall strengthen your heart.” There is really nothing to be depressed about. -

Disney Princesses Trivia Quiz

DISNEY PRINCESSES TRIVIA QUIZ ( www.TriviaChamp.com ) 1> Which princess has the ability to heal? a. Pocahontas b. Jasmine c. Rapunzel d. Megara 2> Which Disney princess is Scottish? a. Jasmine b. Merida c. Megara d. Mulan 3> Which princess sings the song entitled Part of this World? a. Belle b. Ariel c. Tiana d. Pocahontas 4> Which princess wears a green dress? a. Tiana b. Cinderella c. Aurora d. Belle 5> Who is the daughter of King Stefan and Queen Leah? a. Adrina b. Aurora c. Dot d. Eden 6> Which Princess falls in love with Eric? a. Eric b. Ariel c. Belle d. Tiana 7> Which princess is an excellent cook? a. Pocahontas b. Tiana c. Ariel d. Megera 8> What color does Rapunzel wear? a. Yellow b. Purple c. Blue d. Green 9> Which Disney princess dances with an owl? a. Aurora b. Jasmine c. Megara d. Dot 10> Which princess is asked to pour tea for the matchmaker? a. Mulan b. Pocahontas c. Ariel d. Belle 11> Which princess lives in Agrahba? a. Anna b. Jasmine c. Belle d. Rapunzel 12> Which princess falls in love with a thief? a. Cinderella b. Rapunzel c. Merida d. Snow White 13> Which Princess wears pants as part of her "official" costume? a. Belle b. Snow White c. Jasmine d. Cinderella 14> Which princess sings A Dream is a Wish Your Heart Makes? a. Snow White b. Aurora c. Cinderella d. Belle 15> Which princess is invited to be the dinner guest in a magical castle? a. Megara b. -

Tell Your Summer Disney Story!

Tell Your Summer Disney Story! Disney PhotoPass® Guide Walt Disney World® Resort Summer 2019 Magic Kingdom® Park DISNEY ICONS Main Street, U.S.A.® Fantasyland® nnPark Entrance nnPrince Eric’s Castle nnCinderella Castle Frontierland® nnBig Thunder Mountain CHARACTER EXPERIENCES Main Street, U.S.A.® Fantasyland® nnMickey Mouse and Minnie Mouse nnAlice nnTinker Bell nnAriel Cinderella Adventureland® nn Daisy Duck nnAladdin and Princess Jasmine nn nnDonald Duck ® Tomorrowland nnElena of Avalor nnBuzz Lightyear nnGaston nnStitch nnGoofy nnMerida nnPluto nnRapunzel nnTiana nnWinnie the Pooh ATTRACTIONS Adventureland® Liberty Square nnPirates of the Caribbean®* nnHaunted Mansion* Frontierland® Fantasyland® nnSplash Mountain® nnSeven Dwarfs Mine Train* Includes attraction photo & video. Tomorrowland® nnSpace Mountain® nnBuzz Lightyear’s Space Ranger Spin® MAGIC SHOTS Main Entrance Main Street, U.S.A.® nnPeter Pan nnMickey Ice Cream Bar Fantasyland® nnAlice Frontierland® Liberty Square nnAriel nnMr. Bluebird nnHitchhiking Ghosts Cinderella nn Fantasyland® nnDaisy Duck nnNEW! Animated Magic Shot at Ariel’s Grotto nnDonald Duck nnElena of Avalor OTHER PHOTO EXPERIENCES nnGaston nnGoofy Fantasyland® nnMerida nnEnchanted Tales with Belle nnPluto nnDisney PhotoPass Studio Rapunzel nn Main Street, U.S.A.® nnTiana nnNEW! Cinderella Castle PhotoPass Experience at Plaza nnWinnie the Pooh Garden East *MagicBand required at time of capture to link and preview this attraction photo Epcot® DISNEY ICONS Future World nnSpaceship Earth® (Front) nnSpaceship Earth® -

From Snow White to Frozen

From Snow White to Frozen An evaluation of popular gender representation indicators applied to Disney’s princess films __________________________________________________ En utvärdering av populära könsrepresentations-indikatorer tillämpade på Disneys prinsessfilmer __________________________________________________ Johan Nyh __________________________________________________ Faculty: The Institution for Geography, Media and Communication __________________________________________________ Subject: Film studies __________________________________________________ Points: 15hp Master thesis __________________________________________________ Supervisor: Patrik Sjöberg __________________________________________________ Examiner: John Sundholm __________________________________________________ Date: June 25th, 2015 __________________________________________________ Serial number: __________________________________________________ Abstract Simple content analysis methods, such as the Bechdel test and measuring percentage of female talk time or characters, have seen a surge of attention from mainstream media and in social media the last couple of years. Underlying assumptions are generally shared with the gender role socialization model and consequently, an importance is stated, due to a high degree to which impressions from media shape in particular young children’s identification processes. For young girls, the Disney Princesses franchise (with Frozen included) stands out as the number one player commercially as well as in customer awareness. -

A Brave New World (PDF)

Dear Reader: In Spring 2005, as part of Cochise College’s 40th anniversary celebration, we published the first installment of Cochise College: A Brave Beginning by retired faculty member Jack Ziegler. Our reason for doing so was to capture for a new generation the founding of Cochise College and to acknowledge the contributions of those who established the College’s foundation of teaching and learning. A second, major watershed event in the life of the College was the establishment of the Sierra Vista Campus. Dr. Ziegler has once again conducted interviews and researched archived news paper accounts to create a history of the Sierra Vista Campus. As with the first edition of A Brave Beginning, what follows is intended to be informative and entertaining, capturing not only the recorded events but also the memories of those who were part of expanding Cochise College. Dr. Karen Nicodemus As the community of Sierra Vista celebrates its 50th anniversary, the College takes great pleas ure in sharing the establishment of the Cochise College Sierra Vista Campus. Most importantly, as we celebrate the success of our 2006 graduates, we affirm our commitment to providing accessible and affordable higher education throughout Cochise County. For those currently at the College, we look forward to building on the work of those who pio neered the Douglas and Sierra Vista campuses through the College’s emerging districtwide master facilities plan. We remain committed to being your “community” college – a place where teaching and learning is the highest priority and where we are creating opportunities and changing lives. Karen A. -

Best Animated Film: Brave Q. Please Welcome the Bafta Winning Co

Best animated film: Brave Q. Please welcome the Bafta winning co-directors of the Best Animated Film, Pixar's Brave, Mark Andrews and Brenda Chapman. Congratulations guys. MARK ANDREWS: Thank you. Q. How does it feel because Pixar has this long and illustrious history of hoovering up every award in its path so is there pressure on you when you start a project like this? BRENDA CHAPMAN: We don't think -- I don't -- you don't think about it, you're just making the movie then you go oh, an award. MARK ANDREWS: Oh, 13th film, oh yeah, stacked the deck against us, oh yes. Q. So where are these going to go? Is there a big shelf in Pixar? MARK ANDREWS: There is a big thing but I think we'll keep these at our house. Q. Any questions for Brenda and Mark? Thank you. PRESS: You touched on it a little bit there but given Pixar's tremendous history for winning these awards, is it special when the films are recognised that you don't let the side down a little bit? MARK ANDREWS: No, no I think -- I mean it's -- it's great you know when you do win it because we make these films -- no matter how many times Pixar makes films it's always like when you're starting to make a film it's like making a film for the very first time, you know. So when it's released and it gets out there and it's building up all the success and then you get nominated for awards, it's like dreams come true. -

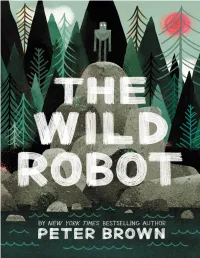

The Wild Robot.Pdf

Begin Reading Table of Contents Copyright Page In accordance with the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, the scanning, uploading, and electronic sharing of any part of this book without the permission of the publisher is unlawful piracy and theft of the author’s intellectual property. If you would like to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), prior written permission must be obtained by contacting the publisher at [email protected]. Thank you for your support of the author’s rights. To the robots of the future CHAPTER 1 THE OCEAN Our story begins on the ocean, with wind and rain and thunder and lightning and waves. A hurricane roared and raged through the night. And in the middle of the chaos, a cargo ship was sinking down down down to the ocean floor. The ship left hundreds of crates floating on the surface. But as the hurricane thrashed and swirled and knocked them around, the crates also began sinking into the depths. One after another, they were swallowed up by the waves, until only five crates remained. By morning the hurricane was gone. There were no clouds, no ships, no land in sight. There was only calm water and clear skies and those five crates lazily bobbing along an ocean current. Days passed. And then a smudge of green appeared on the horizon. As the crates drifted closer, the soft green shapes slowly sharpened into the hard edges of a wild, rocky island. The first crate rode to shore on a tumbling, rumbling wave and then crashed against the rocks with such force that the whole thing burst apart. -

Masculinity in Children's Film

Masculinity in Children’s Film The Academy Award Winners Author: Natalie Kauklija Supervisor: Mariah Larsson Examiner: Tommy Gustafsson Spring 2018 Film Studies Bachelor Thesis Course Code 2FV30E Abstract This study analyzes the evolution of how the male gender is portrayed in five Academy Award winning animated films, starting in the year 2002 when the category was created. Because there have been seventeen award winning films in the animated film category, and there is a limitation regarding the scope for this paper, the winner from every fourth year have been analyzed; resulting in five films. These films are: Shrek (2001), Wallace and Gromit (2005), Up (2009), Frozen (2013) and Coco (2017). The films selected by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in the Animated Feature film category tend to be both critically and financially successful, and watched by children, young adults, and adults worldwide. How male heroes are portrayed are generally believed to affect not only young boys who are forming their identities (especially ages 6-14), but also views on gender behavioral expectations in girls. Key words Children’s Film, Masculinity Portrayals, Hegemonic Masculinity, Masculinity, Film Analysis, Gender, Men, Boys, Animated Film, Kids Film, Kids Movies, Cinema, Movies, Films, Oscars, Ceremony, Film Award, Awards. Table of Contents Introduction __________________________________________________________ 1 Problem Statements ____________________________________________________ 2 Method and Material ____________________________________________________ -

To Infinity and Back Again: Hand-Drawn Aesthetic and Affection for the Past in Pixar's Pioneering Animation

To Infinity and Back Again: Hand-drawn Aesthetic and Affection for the Past in Pixar's Pioneering Animation Haswell, H. (2015). To Infinity and Back Again: Hand-drawn Aesthetic and Affection for the Past in Pixar's Pioneering Animation. Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, 8, [2]. http://www.alphavillejournal.com/Issue8/HTML/ArticleHaswell.html Published in: Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal Publisher rights © 2015 The Authors. This is an open access article published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/), which permits distribution and reproduction for non-commercial purposes, provided the author and source are cited. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact [email protected]. Download date:28. Sep. 2021 1 To Infinity and Back Again: Hand-drawn Aesthetic and Affection for the Past in Pixar’s Pioneering Animation Helen Haswell, Queen’s University Belfast Abstract: In 2011, Pixar Animation Studios released a short film that challenged the contemporary characteristics of digital animation.