A Socio-Religious Custom Gleaned from the Nineteenth Century Palm Leaves

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

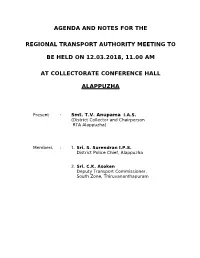

Agenda and Notes for the Regional Transport

AGENDA AND NOTES FOR THE REGIONAL TRANSPORT AUTHORITY MEETING TO BE HELD ON 12.03.2018, 11.00 AM AT COLLECTORATE CONFERENCE HALL ALAPPUZHA Present : Smt. T.V. Anupama I.A.S. (District Collector and Chairperson RTA Alappuzha) Members : 1. Sri. S. Surendran I.P.S. District Police Chief, Alappuzha 2. Sri. C.K. Asoken Deputy Transport Commissioner. South Zone, Thiruvananthapuram Item No. : 01 Ref. No. : G/47041/2017/A Agenda :- To reconsider the application for the grant of fresh regular permit in respect of stage carriage KL-15/9612 on the route Mannancherry – Alappuzha Railway Station via Jetty for 5 years reg. This is an adjourned item of the RTA held on 27.11.2017. Applicant :- The District Transport Ofcer, Alappuzha. Proposed Timings Mannancherry Jetty Alappuzha Railway Station A D P A D 6.02 6.27 6.42 7.26 7.01 6.46 7.37 8.02 8.17 8.58 8.33 8.18 9.13 9.38 9.53 10.38 10.13 9.58 10.46 11.11 11.26 12.24 11.59 11.44 12.41 1.06 1.21 2.49 2.24 2.09 3.02 3.27 3.42 4.46 4.21 4.06 5.19 5.44 5.59 7.05 6.40 6.25 7.14 7.39 7.54 8.48 (Halt) 8.23 8.08 Item No. : 02 Ref. No. G/54623/2017/A Agenda :- To consider the application for the grant of fresh regular permit in respect of a suitable stage carriage on the route Chengannur – Pandalam via Madathumpadi – Puliyoor – Kulickanpalam - Cheriyanadu - Kollakadavu – Kizhakke Jn. -

LIST of FARMS REGISTERED in ALAPPUZHA DISTRICT * Valid for 5 Years from the Date of Issue

LIST OF FARMS REGISTERED IN ALAPPUZHA DISTRICT * Valid for 5 Years from the Date of Issue. Address Farm Address S.No. Registration No. Name Father's / Husband's name Survey Number Issue date * Village / P.O. Mandal District Mandal Revenue Village 1 KL-II-2008(0005) T.K. Koshy Vaidyan Shri Koshy Vaidyan Mappillai Veettil Karthikappally - 690 516 Alappuzha district Karthikappally Karthikappally 255/2, 256/17 04.08.2008 91/4A, 5A, 5B, 131/12-1, 27A, 91/43, 90/3A, 2 KL-II-2008(0006) Abraham Joseph Shri Ouseph Nediyezhathu Vayalar PO- 688 536 Alappuzha district Cherthala Vayalar 15 04.08.2008 K. Ardhasathol 3 KL-II-2008(0007) Bhavan Shri Kandakunju Thattachira Vayalar PO Cherthala Alappuzha district Cherthala Vayalar 14/2, 10/2/A2 04.08.2008 4 KL-II-2008(0008) N.J. Sebastian Shri Ouseph Narakattukalathil Vayalar PO Cherthala Alappuzha district Cherthala Vayalar 2/2-B, 3-C, 4-13 04.08.2008 5 KL-II-2008(0009) T.B. Mohan Das Shri Divakaran Puthenparambil Kadakarapilly PO Cherthala Alappuzha district Cherthala Pattanakad 399/31, 33, 34 04.08.2008 218/12-2, 6 KL-II-2008(0010) Manoj Tharian Shri Varkey Thariath Kallarackal Kadavil Pallippuram (PO) Kizhekkeveettil (H) Cherthala-688 541 Cherthala Pallippuram 218/11-A 04.08.2008 29/3A, 29/3B, 29/3C, 29/A, 29/B, 9/2-1, Thuravoor - 688 29/1, 29/2-1-3, 7 KL-II-2008(0010) Susan Ouseph Shri Ouesph Kallupeedika Valamangalam (PO) 532 Cherthala Thuravoor 29/2-1 04.08.2008 98/12/2-2, 98/12/2-4, 98/11/A-1-3, 8 KL-II-2008(0012) Francis Kuttikkattu House Ezhupunna South (PO) Cherthala-688 550 Alappuzha district Cherthala Kodamthuruth 61/2/B-4 04.08.2008 14/21, 15/24, 9 KL-II-2008(0013) P.V. -

Why Are Relatively Poor People Not More Supportive of Redistribution? Evidence from a Randomized Survey Experiment Across 10 Countries

Why are relatively poor people not more supportive of redistribution? Evidence from a randomized survey experiment across 10 countries By Christopher Hoy and Franziska Mager∗ We test a key assumption of conventional theories about prefer- ences for redistribution, which is that relatively poor people should be the most in favor of redistribution. We conduct a randomized survey experiment with over 30,000 participants across 10 coun- tries, half of whom are informed of their position in the national income distribution. Contrary to prevailing wisdom, people who are told they are relatively poorer than they thought are less con- cerned about inequality and are not more supportive of redistri- bution. This finding is driven by people using their own living standard as a \benchmark" for what they consider acceptable for others. JEL: D31, D63, D72, D83, O50, P16, H23 Keywords: Inequality, Social Mobility, Redistribution, Political Economy Social commentators and researchers struggle to explain why, despite growing inequality in many countries around the world, there is often relatively limited support among poorer ∗ Hoy: Australian National University, JG Crawford Building, 132 Lennox Crossing, Acton Australian Capital Territory 0200 Australia, [email protected]. Mager: Oxfam Great Britain, Oxfam Great Britain Oxfam House John Smith Drive Oxford OX4 2JY United Kingdom, [email protected]. The authors are very grateful for detailed comments provided on an earlier version of this paper by Michael Norton, Daniel Treisman, Elisabeth Bublitz, Edoardo Teso, Christopher Roth, Russell Toth, Eva Vivalt, Stephen Howes, Emma Samman, Mathias Sinning, Deborah Hardoon, David Hope, Alice Krozer, David McArthur and Ben Goldsmith. -

Hari Nair 915-747-7544 | [email protected] | Web |

Hari Nair 915-747-7544 j [email protected] j web j Appointments The University of Texas at El Paso El Paso, TX Assistant Professor, Department of Physics Sep. 2018 { present The University of Texas at El Paso El Paso, TX Visiting Assistant Professor, Department of Physics Sep. 2017 { Sep. 2018 Colorado State University Fort Collins, CO, USA Postdoctoral Researcher, Department of Physics Feb 2016 { Aug 2017 University of Johannesburg Johannesburg, South Africa Postdoctoral Researcher, Department of Physics Oct 2014 { Dec 2015 JCNS-2 & Peter Grunberg Institute J¨ulich, Germany Scientific Staff, Forschungszentrum J¨ulichGmbH Apr 2011 { Jul2014 Indian Institute of Science Bangalore, India Postdoctoral Researcher, Department of Physics Feb 2011 { Apr 2011 Indian Institute of Science Bangalore, India Researcher, Department of Physics Oct 2009 { Sep 2010 Visiting positions Universitat zu K¨oln K¨oln,Germany Researcher, II. Physikalisches Institut Oct 2010 { Jan 2011 Forschungszentrum J¨ulich GmbH J¨ulich, Germany Visiting Researcher, Institut fur Festk¨orperforschung (IFF) Jun 2009 { Sep 2009 Max Planck Institute for Chemical Physics of Solids Dresden, Germany Visiting Researcher May 2008 { Jul 2008 Leibniz Institute for Solid State and Materials Research Dresden, Germany Visiting Researcher Oct 2006 { Dec 2006 Education Indian Institute of Science Bangalore, India PhD in experimental condensed matter physics Jun. 2002 { Dec. 2009 Mahatma Gandhi University Kerala, India MSc in Physics from C. M. S. College 2000 { 2002 Kerala University Kerala, India BSc in Physics from T. K. M. College 1997 { 2000 Grants/ Awards/ Honours 2020: (1) coPI in National Science Foundation Major Research Instrumentation program award to UTEP to acquire an MPMS. -

Religion and the Abolition of Slavery: a Comparative Approach

Religions and the abolition of slavery - a comparative approach William G. Clarence-Smith Economic historians tend to see religion as justifying servitude, or perhaps as ameliorating the conditions of slaves and serving to make abolition acceptable, but rarely as a causative factor in the evolution of the ‘peculiar institution.’ In the hallowed traditions, slavery emerges from scarcity of labour and abundance of land. This may be a mistake. If culture is to humans what water is to fish, the relationship between slavery and religion might be stood on its head. It takes a culture that sees certain human beings as chattels, or livestock, for labour to be structured in particular ways. If religions profoundly affected labour opportunities in societies, it becomes all the more important to understand how perceptions of slavery differed and changed. It is customary to draw a distinction between Christian sensitivity to slavery, and the ingrained conservatism of other faiths, but all world religions have wrestled with the problem of slavery. Moreover, all have hesitated between sanctioning and condemning the 'embarrassing institution.' Acceptance of slavery lasted for centuries, and yet went hand in hand with doubts, criticisms, and occasional outright condemnations. Hinduism The roots of slavery stretch back to the earliest Hindu texts, and belief in reincarnation led to the interpretation of slavery as retribution for evil deeds in an earlier life. Servile status originated chiefly from capture in war, birth to a bondwoman, sale of self and children, debt, or judicial procedures. Caste and slavery overlapped considerably, but were far from being identical. Brahmins tried to have themselves exempted from servitude, and more generally to ensure that no slave should belong to 1 someone from a lower caste. -

History Narrated in Gowriyamma's

ISSN:2277-7881; IMPACT FACTOR :6.514(2021); IC VALUE:5.16; ISI VALUE:2.286 Peer Reviewed and Refereed Journal: VOLUME:10, ISSUE:3(6), March:2021 Online Copy Available: www.ijmer.in HISTORY NARRATED IN GOWRIYAMMA’S ‘ATHMAKATHA’ Dipu P K Assistant Professor Department of History, Maharajas Collage Ernakulam, Kerala, India Abstract Kerala history is enriched by large number of Autobiographies by prominent persons. There are so many gaps in existing history of Kerala. Autobiography to some extend fills the gap. Autobiography written by political leaders, literary writers, social activist contribute to socio economic history of Kerala. Autobiographies contains details about social reform activities, struggle for responsible and cultural history. Jeevithasamaram of C Kesavan, Smrithidharppanam of M. PManmadan, Kazhinjakalam of K.P.Kesavamenonetc are important autobiographies. Gowriyamma’s autobiography Athmakatha also included in this category. Gowriyamma’s early life witnessed anti cast movement, rise and growth of political movement and ending of princely state. The background of Gowriyamma’sAthmakadha was provided by these movements. Keywords: Athmakatha, Janmi, Kudiyan, Avarna, Devaswom, Pattom, Chethala T, Ezhava, SNDP. Introduction Autobiography has become an important genre for literary –critical discourse. What is important about autobiographical writing is that it is an act of a conscious self which is documented through the active help of memory1.Writing an autobiography is a political act because there is always an assertion of the narrative self2. Nirad C Chaudhuri says in his autobiography “My main intention is thus historical and since I have written the account with the utmost honesty and accuracy of which I am able, the intention in my mind has become mingled with the aspiration that the book may be regarded as a contribution to contemporary histoty3”. -

Is Caste System Prevalent Among the Syrian Christians of Kerala? a Critical Analysis

Vol. 5 No. 3 January 2018 ISSN: 2321-788X UGC Approval No: 43960 Impact Factor: 2.114 IS CASTE SYSTEM PREVALENT AMONG THE SYRIAN CHRISTIANS OF KERALA? A CRITICAL ANALYSIS THOMAS P JOHN Assistant Professor in History St. Xavier’s College, Thumba, Kerala, India Article Particulars: Received: 25.11.2017 Accepted: 06.12.2017 Published: 20.01.2018 Abstract The concept of caste has ever been a reality in all societies and countries, and yet there exists some ambiguities in understanding the concept of caste in some communities. A great confusion exists among the academicians as well as in the general public about the concept of caste in the Syrian Christian community in Kerala. The multiplicity of denominations among them, each having their own Rite, Liturgy, Clergy, Ecclesial hierarchy etc. had created great confusion among the people especially among the non Christians. Vague ideas had taken position and a majority including learned historians and thinkers are totally mistaken in this regard. Some interpret these varieties as separate castes. Hence, an earnest attempt to find out the truth in this matter is urgent. This article is an attempt to deactivate the wrong concepts about the caste factor in the Syrian Christian community and to replace it with the most reasonable and genuine knowledge of the same. It finds out that all the different Syrian Christian groups except the ‘Knanites’ forms one single cast and the difference is only denominational. Keywords: Caste, Religion, Syrian Christians, St. Thomas Tradition, Synod of Diamper, Coonnan Cross Oath, ‘Mission of Help’ Malankara, Jacobite, Knanaya, Marthoma Syrian, Pazhayakooru, Puthenkooru, Idavaka. -

List of Offices Under the Department of Registration

1 List of Offices under the Department of Registration District in Name& Location of Telephone Sl No which Office Address for Communication Designated Officer Office Number located 0471- O/o Inspector General of Registration, 1 IGR office Trivandrum Administrative officer 2472110/247211 Vanchiyoor, Tvpm 8/2474782 District Registrar Transport Bhavan,Fort P.O District Registrar 2 (GL)Office, Trivandrum 0471-2471868 Thiruvananthapuram-695023 General Thiruvananthapuram District Registrar Transport Bhavan,Fort P.O District Registrar 3 (Audit) Office, Trivandrum 0471-2471869 Thiruvananthapuram-695024 Audit Thiruvananthapuram Amaravila P.O , Thiruvananthapuram 4 Amaravila Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0471-2234399 Pin -695122 Near Post Office, Aryanad P.O., 5 Aryanadu Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0472-2851940 Thiruvananthapuram Kacherry Jn., Attingal P.O. , 6 Attingal Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0470-2623320 Thiruvananthapuram- 695101 Thenpamuttam,BalaramapuramP.O., 7 Balaramapuram Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0471-2403022 Thiruvananthapuram Near Killippalam Bridge, Karamana 8 Chalai Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0471-2345473 P.O. Thiruvananthapuram -695002 Chirayinkil P.O., Thiruvananthapuram - 9 Chirayinkeezhu Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0470-2645060 695304 Kadakkavoor, Thiruvananthapuram - 10 Kadakkavoor Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0470-2658570 695306 11 Kallara Trivandrum Kallara, Thiruvananthapuram -695608 Sub Registrar 0472-2860140 Kanjiramkulam P.O., 12 Kanjiramkulam Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0471-2264143 Thiruvananthapuram- 695524 Kanyakulangara,Vembayam P.O. 13 -

Document Edit Form

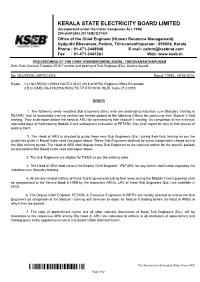

KERALA STATE ELECTRICITY BOARD LIMITED (Incorporated under the Indian Companies Act, 1956) CIN-U40100KL2011SGCO27424 Office of the Chief Engineer (Human Resource Management) Vydyuthi Bhavanam, Pattom, Thiruvananthapuram - 695004, Kerala Phone : 91-471-2448948 E-mail: [email protected] Fax : 91-471-2441361 Web: www.kseb.in. PROCEEDINGS OF THE CHIEF ENGINEER(HRM) KSEBL, THIRUVANANTHAPURAM Sub:-Estt:-General Transfer 2018-Transfer and posting of Sub Engineer(Ele)- Orders issued. No. EB2/SE(Ele.)/KPSC/2018 Dated, TVPM., 29-06-2018 Read:- 1.Lr.NO.REIII(I)1459/14 DATED 03.02.2018 of KPSC Regional Office Ernakulam 2.B.O (CMD) No.819/2018(HRD).7/ILTP-STP/2018-19) Dt.Tvpm 27.3.2018 ORDER 1. The following newly recruited Sub Engineers (Ele.) who are undergoing Induction cum Statutory training at PETARC and its associated training centers are hereby posted to the following Offices for continuing their Module II field training. They shall report before the head of ARU for commencing their Module II training. On completion of the minimum stipulated days of field training Module II and subsequent evaluation at PETARC they shall report for duty in their places of posting itself. 2. The Head of ARU is directed to guide these new Sub Engineers (Ele.) during their field training as per the guidelines given in Board Order read 2nd paper above. These Sub Engineers shall not be given independent charge during the field training period. The Head of ARU shall depute these Sub Engineers to the required station for the specific periods as stipulated in the Board Order read 2nd paper above. -

List of Lacs with Local Body Segments (PDF

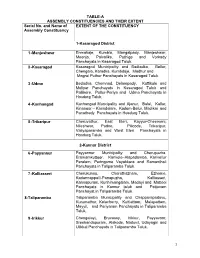

TABLE-A ASSEMBLY CONSTITUENCIES AND THEIR EXTENT Serial No. and Name of EXTENT OF THE CONSTITUENCY Assembly Constituency 1-Kasaragod District 1 -Manjeshwar Enmakaje, Kumbla, Mangalpady, Manjeshwar, Meenja, Paivalike, Puthige and Vorkady Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk. 2 -Kasaragod Kasaragod Municipality and Badiadka, Bellur, Chengala, Karadka, Kumbdaje, Madhur and Mogral Puthur Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk. 3 -Udma Bedadka, Chemnad, Delampady, Kuttikole and Muliyar Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk and Pallikere, Pullur-Periya and Udma Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 4 -Kanhangad Kanhangad Muncipality and Ajanur, Balal, Kallar, Kinanoor – Karindalam, Kodom-Belur, Madikai and Panathady Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 5 -Trikaripur Cheruvathur, East Eleri, Kayyur-Cheemeni, Nileshwar, Padne, Pilicode, Trikaripur, Valiyaparamba and West Eleri Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 2-Kannur District 6 -Payyannur Payyannur Municipality and Cherupuzha, Eramamkuttoor, Kankole–Alapadamba, Karivellur Peralam, Peringome Vayakkara and Ramanthali Panchayats in Taliparamba Taluk. 7 -Kalliasseri Cherukunnu, Cheruthazham, Ezhome, Kadannappalli-Panapuzha, Kalliasseri, Kannapuram, Kunhimangalam, Madayi and Mattool Panchayats in Kannur taluk and Pattuvam Panchayat in Taliparamba Taluk. 8-Taliparamba Taliparamba Municipality and Chapparapadavu, Kurumathur, Kolacherry, Kuttiattoor, Malapattam, Mayyil, and Pariyaram Panchayats in Taliparamba Taluk. 9 -Irikkur Chengalayi, Eruvassy, Irikkur, Payyavoor, Sreekandapuram, Alakode, Naduvil, Udayagiri and Ulikkal Panchayats in Taliparamba -

Preliminary Pages.Qxd

State Formation and Radical Democracy in India State Formation and Radical Democracy in India analyses one of the most important cases of developmental change in the twentieth century, namely, Kerala in southern India, and asks whether insurgency among the marginalized poor can use formal representative democracy to create better life chances. Going back to pre-independence, colonial India, Manali Desai takes a long historical view of Kerala and compares it with the state of West Bengal, which like Kerala has been ruled by leftists but has not experienced the same degree of success in raising equal access to welfare, literacy and basic subsistence. This comparison brings historical state legacies, as well as the role of left party formation and its mode of insertion in civil society to the fore, raising the question of what kinds of parties can effect the most substantive anti-poverty reforms within a vibrant democracy. This book offers a new, historically based explanation for Kerala’s post- independence political and economic direction, drawing on several comparative cases to formulate a substantive theory as to why Kerala has succeeded in spite of the widespread assumption that the Indian state has largely failed. Drawing conclusions that offer a divergence from the prevalent wisdoms in the field, this book will appeal to a wide audience of historians and political scientists, as well as non-governmental activists, policy-makers, and those interested in Asian politics and history. Manali Desai is Lecturer in the Department of Sociology, University of Kent, UK. Asia’s Transformations Edited by Mark Selden Binghamton and Cornell Universities, USA The books in this series explore the political, social, economic and cultural consequences of Asia’s transformations in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. -

Cherthala School Code Sub District Name of School School Type 34337 Thuravoor GUPS Thycattussery G 34009 Thuravoor HSS Kandamang

Cherthala School Code Sub District Name of School School Type 34337 Thuravoor GUPS Thycattussery G 34009 Thuravoor HSS Kandamangalam A 34330 Thuravoor GLPS Thaliyaparambu G 34331 Thuravoor GLPS Mattathil Bhagam G 34332 Thuravoor St. Francis Xaviers LPS Eramalloor A 34333 Thuravoor BBM LPS Azheekal A 34334 Thuravoor GUPS Arookutty G 34328 Thuravoor St. Marys LPS Srambickal A 34336 Thuravoor GUPS Uzhuva G 34327 Thuravoor NSS LPS Panavally A 34338 Thuravoor GUPS Kadakkarappally G 34339 Thuravoor GUPS Odampally G 34340 Thuravoor GUPS Parayakad G 34341 Thuravoor GUPS Changaram G 34342 Thuravoor St. Martins UPS Neendakara A 34004 Thuravoor St. Augustines KSS Aroor A 34343 Thuravoor NI UPS Naduvath Nagar A 34335 Thuravoor GUPS Thuravor West G 34320 Thuravoor SN LPS Ezhupunna A 34007 Cherthala Govt HS Pollathai G 34006 Cherthala Govt HSS Kalavoor G 34003 Cherthala St. Augustines HS Mararikulam A 34002 Cherthala Govt.Fisheries HS Arthungal G 34001 Cherthala SFA HSS Arthunkal A 34318 Thuravoor Govt TD LPS Thuravoor G 34329 Thuravoor St. Mary Immaculate LPS Ezhupunna A 34319 Thuravoor St.Augustines LPS Aroor A 34010 Thuravoor Sr. Georges HS Thankey A 34321 Thuravoor St. Thomas LPS Pallithode A 34322 Thuravoor LFM LPS Manakkodam Pattam A 34323 Thuravoor St. Josephs LPS Ottamassery A 34317 Thuravoor GLPS Konattussery G 34324 Thuravoor St. Josephs LPS Uzhuva A 34325 Thuravoor Thuravoor Panchayath LPS A 34326 Thuravoor MAM LPS Panavally A 34253 Cherthala KPM UPS Muhamma A 34312 Thuravoor LPGS Perumpalam G 34005 Thuravoor Govt HS Aroor G 34305 Thuravoor