Disciplinary Board Reporter, Volume 27

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

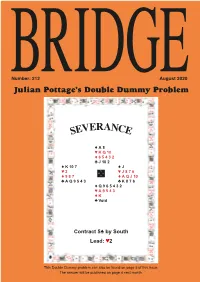

SEVERANCE © Mr Bridge ( 01483 489961

Number: 212 August 2020 BRIDGEJulian Pottage’s Double Dummy Problem VER ANCE SE ♠ A 8 ♥ K Q 10 ♦ 6 5 4 3 2 ♣ J 10 2 ♠ K 10 7 ♠ J ♥ N ♥ 2 W E J 8 7 6 ♦ 9 8 7 S ♦ A Q J 10 ♣ A Q 9 5 4 3 ♣ K 8 7 6 ♠ Q 9 6 5 4 3 2 ♥ A 9 5 4 3 ♦ K ♣ Void Contract 5♠ by South Lead: ♥2 This Double Dummy problem can also be found on page 5 of this issue. The answer will be published on page 4 next month. of the audiences shown in immediately to keep my Bernard’s DVDs would put account safe. Of course that READERS’ their composition at 70% leads straight away to the female. When Bernard puts question: if I change my another bidding quiz up on Mr Bridge password now, the screen in his YouTube what is to stop whoever session, the storm of answers originally hacked into LETTERS which suddenly hits the chat the website from doing stream comes mostly from so again and stealing DOUBLE DOSE: Part One gives the impression that women. There is nothing my new password? In recent weeks, some fans of subscriptions are expected wrong in having a retinue. More importantly, why Bernard Magee have taken to be as much charitable The number of occasions haven’t users been an enormous leap of faith. as they are commercial. in these sessions when warned of this data They have signed up for a By comparison, Andrew Bernard has resorted to his breach by Mr Bridge? website with very little idea Robson’s website charges expression “Partner, I’m I should add that I have of what it will look like, at £7.99 plus VAT per month — excited” has been thankfully 160 passwords according a ‘founder member’s’ rate that’s £9.59 in total — once small. -

Bridge Table Des Matières

Bridge Table des matières 1 Glossaire du bridge 1 1.1 A ................................................... 1 1.1.1 Acol ............................................. 1 1.1.2 Affranchir .......................................... 1 1.1.3 Agrément ........................................... 1 1.1.4 Alerte ............................................. 1 1.1.5 Annonce ........................................... 1 1.1.6 Annonces (les) ........................................ 1 1.1.7 Appel ............................................. 2 1.1.8 Artificiel ........................................... 2 1.1.9 Atout ............................................. 2 1.1.10 Attaque ............................................ 2 1.1.11 Attaquer ........................................... 2 1.2 B ................................................... 2 1.2.1 Barrage ............................................ 2 1.2.2 Bath (coup de) ........................................ 2 1.2.3 Bermuda Bowl ........................................ 2 1.2.4 Bicolore ........................................... 2 1.2.5 Bidding Box .......................................... 2 1.2.6 Blackwood .......................................... 2 1.2.7 Board ............................................. 2 1.2.8 Boitier d'enchères ...................................... 2 1.2.9 Butler ............................................. 3 1.3 C ................................................... 3 1.3.1 Camp ............................................. 3 1.3.2 Canapé ........................................... -

TOWNSHIP with the SUBURBAN NEWSPAPER LARGEST in GUARANTEED THIS AREA CIRCULATION "The Voice of the Raritan Bay District" VOL

SJMaa»ti»BgjCTiiigpa"ia»iap-rfi-jratjS'^ &&&?Wj&.&&zswtt&*?in^--\'i/'-'*v-*?^-tt*-xx'& RARITAN MOST PROGRESSIVE TOWNSHIP WITH THE SUBURBAN NEWSPAPER LARGEST IN GUARANTEED THIS AREA CIRCULATION "The Voice of the Raritan Bay District" VOL. IV. — NO. 12. FORDS AND RARITAN TOWNSHIP FRIDAY MORNING, MAY 19, 1939. PRICE THREE CENTS JULIUS ENGEL BIDS FAREWELL TO HAROLD BERRUE Can This Be Called A 'Death Trap'? SZALLAR NAMED Rumoured COMMISSION AFTER LONG SERVICE POST TO ERECT TO FORCE AFTER Election RARITAN TOWNSHIP.—Sev-'re-election .since his work prohib- enteen years of brilliant and un- f ited their activities. He was the on MEMORIAL ROCK LONG 'POW-WOW Post Mortems ... tiring public service to the resi- ly Democratic member of the The commissioners of Raritan Township are still get- dents of the township was con- commission and the only original TO BE PLACED ON FRONT BERGEN, ALEXANDER VOTE ting lots and lots of congratulatory messages from the cluded here last week when member of the body since its orig- 'NO' FOR FAILURE TO happy taxpayers of the township who worked for their;sheriff Julius c- Engel- a member in. LAWN OF NEW TOWN Engel took his first public office CONSULT THEM election eleven days ago . Dr. Edward K. Hanson, of[ as tax collector in 1922 and has HALL. NOV. 11 Clara Barton section, general chairman of the successful' been active in township affairs WOODBRIDGE.—After months Administration Ticket, also continues to receive hundreds! ever since. In 1927, when the town PISCATAWAYTOWN. — A me- of controversy on the part of the of letters of praise for his brilliant work in guiding his can- ship voted to abolish the township morial stone, which will serve as Republican big whigs, Frank Szal- committee and establish the com- a lasting tribute to veterans of all lar, 35, of Fords, was named pa- didates to victory . -

The Accidental Life Master Attendance

Wednesday, July 28, 2010 Volume 82, Number 6 Daily Bulletin 82nd North American Bridge Championships Editors: Brent Manley and Paul Linxwiler Cohen squad grabs Four teams left in Wagar KO The four teams remaining in the Wagar Senior Swiss crown Women’s Knockout Teams will do battle today to The team of Ken see who makes it to the championship round. Cohen, Neal Satten, The matchups, by captain, are Sam Dinkin Rick Rowland (npc) versus Geeske Joel and Valerie Westheimer and Thomas Weik versus Sylvia Moss. overcame a rocky In Tuesday’s quarterfinal round, No. 1 seed start in the Truscott/ Dinkin played only three quarters against the U.S. Playing Card No. 8 seed led by Joann Glasson before the latter Senior Swiss Teams withdrew facing a 155-85 deficit. to win the four- In the other matches, No. 2 Westheimer session contest. It defeated No. 7 Phyllis Fireman 132-109; No. was the first NABC 6 Sylvia Moss, down 6 IMPs with a quarter to victory for Satten, go, won the final set by 50 IMPs to prevail 157- Rowland and Weik, 113 over No. 3 Connie Goldberg, and No. 4 Joel but the fourth for knocked off No. 5 Susan Miller 122-94. captain Cohen. In the qualifying Schwartz, O’Rourke exit round, the Cohen Spingold in Round 2 squad was below The top-seeded squad led by Richard Schwartz average at halftime. was upset in second-round action in the Spingold A solid second half, Truscott/USPC Senior Swiss champs Rick Rowland, Neal Satten, Thomas Weik and Ken Cohen. -

Le Langage Du Bridge 2019

Le langage du bridge Abattement Diminution d’une saison à l’autre du nombre de points de classement (PE, PP°) détenus par les joueurs. Il est défini dans le Règlement du Classement National en vigueur. Acol Système d’enchères naturel, joué surtout en Grande Bretagne. Adversaire Un adversaire est un joueur du camp adverse ; un joueur de la paire à laquelle quelqu’un est opposé. Adversaire dangereux Celui des adversaires qui peut mettre en danger le contrat du déclarant s’il prend la main. Affranchir un honneur Affranchir un honneur consiste à rendre maître un honneur en faisant tomber le(s) honneur(s) supérieur(s) détenu(s) par l’adversaire. Affranchir une couleur On affranchit une couleur lorsque l’on rend maîtresse des cartes intermédiaires qui ne l’étaient pas au début de la partie en épuisant les cartes maîtresses de l’adversaire. Affranchissement Manœuvre consistant à affranchir une carte ou une couleur. Alerte L’alerte est une procédure d’avertissement informant les adversaires que le partenaire a fait une annonce conventionnelle. Alerter Action de faire une « Alerte ». Annoncer Participer à l'ensemble des déclarations faites pour l'attribution du contrat final. Annonces Les annonces peuvent être : Le processus visant à déterminer le contrat final au moyen de déclarations successives. Il commence quand la première déclaration est faite. L’ensemble des déclarations faites. Annulé Voir « Retiré ». Appel Carte jouée par un défenseur pour marquer un intérêt pour une couleur donnée. Appel de préférence Carte jouée par un défenseur, marquant un intérêt pour une autre couleur : une grosse carte pour la plus chère des couleurs restantes, une petite carte pour la moins chère. -

Poland Ukraine Fanguide Euro2012 CONTENTS Fanguide 2012 - Contents

Poland Ukraine Fanguide euro2012 CONTENTS Fanguide 2012 - Contents Contents 03 04 Foreword FSE/UEFA Welcome to Poland/Ukraine 06 Poland A-Z 08 Group A - Warsaw 14 Group A - Wrocław 16 Group A - Competing Countries 18 Group C - Gdańsk 22 Group C - Poznań 24 Group C - Competing Countries 26 Contents 30 Safety and Security 03 Match Schedule 32 34 Ukraine A-Z 40 Group B - Lviv 42 Group B - Kharkiv 44 Group B - Competing Countries 48 Group D - Kiev 50 Group D - Donetsk 52 Group D - Competing Countries Information for disabled fans 56 58 Words and Phrases - Ukraine Words and Phrases - Poland 60 62 Respect fansembassy.org // 2012fanguide.org // facebook.com/FansEmbassies // Twitter @FansEmbassies Foreword from FSE FSE Foreword from UEFA UEFA More than just a tourist guide… The thinking behind what we do is simple: supporters are the heart of football. If Welcome to Poland and Ukraine; These initiatives offer knowledge and insights Dear football supporters from all over you view fans coming to a tournament welcome to UEFA EURO 2012 from those who know best – your fellow Europe, Welcome to Euro 2012, as guests to be treated with respect and supporters. A key factor of the concept is Foreword from FSE and welcome to Poland and Ukraine! not as a security risk to be handled by “The supporters are the lifeblood of the production of fan guides with practical Foreword from UEFA police forces, they will behave accordingly. football“– that belief has formed UEFA’s information in different languages but, 04 What you are holding in your hands right They will enjoy themselves, party attitude towards football fans throughout most importantly, written in our common 05 now is the Football Supporters Europe (FSE) together and create a great atmosphere. -

Scientific Programme by Day Saturday, October 2, 2021

UEG Week Final Programme Saturday, October 2, 2021 Scientific Programme by Day Saturday, October 2, 2021 Vienna Live Session 18:00 – 18:45 TV Studio The UEG Week Premiere Chairs: Axel Dignass, DE Herbert Tilg, AT Helena Cortez-Pinto, PT 1 / 234 Audience Voting Case-Based Live Stream Question & Answer Recorded Session Debate Tandem Talk National Scholar Best Abstract Prize Rising Star UEG Week Final Programme Sunday, October 3, 2021 Scientific Programme by Day Live Session Sunday, October 3, 2021 09:00 – 10:00 Hall 1 Artificial intelligence: Impact for the lower GI tract Vienna Live Session Chairs: Daan W. Hommes, NL Eyal Klang, IL 08:00 – 09:00 TV Studio Opening Chairs: Herbert Tilg, AT Axel Dignass, DE 09:00 - 09:20 IP009 Helena Cortez-Pinto, PT Polyp detection and characterisation Cesare Hassan, IT 09:20 - 09:40 IP010 08:00 - 08:10 IP001 Role of AI in IBD endoscopy Words of welcome Raf Bisschops, BE Herbert Tilg, AT Axel Dignass, DE 09:40 - 10:00 IP011 IBD treatment algorithm driven by AI 08:10 - 08:25 IP002 Silvio Danese, IT NAFLD: From basic mechanisms to new therapies Elisabetta Bugianesi, IT Live Session 08:25 - 08:40 IP003 09:00 – 10:00 Hall 2 Endoscopic strategies targeting metabolic disorders Cutting edge approaches to the treatment of rectal Jacques Deviere, BE cancer 08:40 - 08:45 IP004 Chairs: Thomas Rösch, DE Antonino Spinelli, IT From T-cells to nutritional advice Nadine Cerf-Bensussan, FR 08:45 - 08:50 IP005 09:00 - 09:20 IP012 From T-cells to nutritional advice Imaging in early rectal cancer Raanan Shamir, IL Regina G.H. -

3001Thingsyoudidnotknow.Pdf

Hello and thank you for downloading my book. If you want to save this publication to your computer, please click above on “File”, then click on “Save as” or “Save Page As” or “Save a Copy” and you’re done! Just keep in mind where exactly you save it. Now, if you want to send a copy of this book to a family member, friend, coworker, or a person you know, then all you have to do is give them the following web address: http://TheArtOfPamela.com/3001ThingsYouDidNotKnow.pdf Once this address is submitted in their web browser, they will be able “INSTANTLY” to start downloading a copy of this book. They will obtain it exactly the same way you did, in just a few seconds. Feel free to share this address (this book) with ANYONE you like, via Email, or through social networks like Facebook, Twitter, Google Plus, etc. Okay, let’s stop talking, and let’s read this book now. ENJOY!!! Thank you. Pamela Johnson. http://www.TheArtOfPamela.com (Please, support my creativity!) It takes six months to build a Rolls Royce, and 13 hours to build a Toyota. Karaoke means "empty orchestra" in Japanese. Obama is left-handed, the sixth post-war president to be left-handed. The creator of the NIKE Swoosh symbol (Caroline Davidson) was paid only $35 for the design. The first shoe with the Swoosh was introduced in 1972. You can't create a folder called “Con” in Microsoft Windows. Organs you can donate include: kidneys, heart, liver, pancreas, intestines, lungs, skin, bone and bone marrow, and cornea. -

Events Commemorate Holocaust Tragedy

WEATHER INSIDE TODAY: partly cloudy EDITORIAL 12 chance of thunderstorms FOCUS 17 High: mid 70s Low: 50 STYLE 23 FRIDAY: partly cloudy SPORTS 28 High: 65 Low: 46 HUMOR -33 CLASSIFIEDS 37 JAMES MADISON UNIVERSITY THURSDAY APRIL 27, 1995 VOL. 72, NO. 52 Events commemorate Holocaust tragedy by Paula Finkelstein Concentration camp survivor Anton Segore contributing writer spoke to a crowd of more than 400 about his experiences in Germany, Hungary and Poland Although about 50 years have passed since during World War II, and about current the Allies liberated the gruesome Nazi problems with anti-Semitism, bigotry and concentration camps, the memory of those who hatred. perished there lives on. Junior Steven Hoffman, president of Hillel, To honor and commemorate the people who said he had planned for anywhere from 150 to died, JMU recognized Holocaust Remembrance 400 people to attend Segore's speech. He said Day on Monday with activities and events he was very pleased with the turnout. sponsored by two campus student groups. Segore is a survivor of four concentration B*nai B'rith Hillel. JMU's Jewish campus camps in Germany and Poland — Auschwitz- organization, arranged a day of events in honor Birkenau. Buchenwald, Mauthausen and of those who perished in the Holocaust 50 years Gunskirchen. He was liberated in 1945 while at ago. Interfaith Campus Ministries also the Gunskirchen camp. sponsored the activities. Although he lived in concentration camps Monday's events included an all-day exhibit for only a little more than a year, Segore said he in the Phillips Hall Ballroom displaying copies has painful memories that have stayed with him of actual German documents collected by the for a lifetime. -

Jill Courtney Nigel Dutton Maura Rhodes Di Brooks

O Volume 11 O Issue 11 ODecember O 2011 BRIDGE ASSOCIATION OF WA INC. FOSTERING BRIDGE IN WESTERN AUSTRALIA focus Nigel Dutton Jill Courtney Page 39-40 Di Brooks Maura Rhodes “Fostering Bridge in WA” 1 Richard Fox♣Jill Courtney♣Nigel Dutton♣John Aquino♣Di Brooks♣John Beddow♣Ron Klinger♣Maura Rhodes♣Elaine Khan♣Chris Mulley♣David Schokman♣Michael Stewart♣Gerry Daly♣Allison Stralow♣Di Robinson♣John Penman♣Andy Leal♣Glenda Barter♣Ian Oldham♣Jean Culloton♣Darrel Williams♣Kitty George♣Jane Moulden♣Neville Walker♣Ann Shalders♣Ian Jones♣Sue Lia♣Tony Martin♣Ann Hopfmueller♣Margaret Newton♣Lyndi Trevean♣Nils Andersson♣Jim Smith♣Michael Courtney♣Leonie Fuller♣Lii Soots♣Alison Rigg♣Allan Doig♣Pam Wadsworth♣Mike Wadsworth♣Fiske Warren♣Dave Munro♣Elizabeth McNeill♣John Hughes♣Eugene Wichems♣Robina McConnell♣Peter Holloway♣Marie Musitano♣Ross Harper♣Dennis Yovich♣Kathy Power♣Alexander Long♣Richard Fox♣Jill Courtney♣Nigel Dutton♣John Aquino♣Di Brooks♣John Beddow♣Ron Klinger♣Maura Rhodes♣Elaine Khan♣Chris Mulley♣David Schokman♣Michael Stewart♣Gerry Daly♣Allison Stralow♣Di Robinson♣John Penman♣Andy Leal♣Glenda Barter♣Ian Oldham♣Jean Culloton♣Darrel Williams♣Kitty George♣Jane Moulden♣Neville Walker♣Ann Shalders♣Ian Jones♣Sue Lia♣Tony Martin♣Ann Hopfmueller♣Margaret Newton♣Lyndi Trevean♣Nils Andersson♣Jim Smith♣Michael Courtney♣Leonie Fuller♣Lii Soots♣Alison Rigg♣Allan Doig♣Pam Wadsworth♣Mike Wadsworth♣Fiske Warren♣Dave Munro♣Elizabeth McNeill♣John Hughes♣Eugene Wichems♣Robina McConnell♣Peter Holloway♣Marie Musitano♣Ross Harper♣Dennis Yovich♣Kathy Power♣Alexander -

Bernard Magee's Acol Bidding Quiz

Number: 168 UK £3.95 Europe €5.00 December 2016 Bernard Magee’s Acol Bidding Quiz This month we are dealing with the fifth bid of an auction. You are West in the auctions below, BRIDGEplaying ‘Standard Acol’ with a weak no-trump (12-14 points) and four-card majors. 1. Dealer West. Love All. 4. Dealer West. Love All. 7. Dealer West. Love All. 10. Dealer West. Love All. ♠ K Q 3 ♠ 7 ♠ 2 ♠ K 4 ♥ K 8 7 6 N ♥ A K 4 3 2 N ♥ A K 8 7 2 N ♥ 7 6 N W E W E W E W E ♦ A J ♦ J 5 3 ♦ K 4 2 ♦ 8 4 3 S S S S ♣ A 7 6 5 ♣ A Q 7 6 ♣ Q J 4 2 ♣ A K J 7 6 5 West North East South West North East South West North East South West North East South 1♥ Pass 1♠ Pass 1♥ Pass 1♠ Pass 1♥ Pass 1♠ Pass 1♣ Pass 1♥ Pass 1NT1 Pass 2NT Pass 2♣ Pass 2♠ Pass 2♣ Pass 2♦1 Pass 2♣ Pass 2♦ Pass ? 115-17 balanced ? ? 1Fourth suit forcing ? 2. Dealer West. Love All. 5. Dealer West. Love All. 8. Dealer West. Love All. 11. Dealer West. Love All. ♠ K Q 3 ♠ 9 ♠ 2 ♠ 3 N ♥ A K 6 5 4 N ♥ K Q 6 5 4 N ♥ A K 8 7 2 ♥ Q 2 N W E ♦ W E ♦ W E ♦ ♦ W E K Q 3 A 4 2 J 4 S A K 8 7 6 ♣ 6 2 S ♣ K Q 5 4 S ♣ Q J 9 4 2 ♣ A K 8 4 2 S West North East South West North East South West North East South West North East South 1♥ Pass 1NT Pass 1♥ Pass 1♠ Pass 1♥ Pass 1♠ Pass 1♦ Pass 1♥ Pass 2NT Pass 3♣ Pass 2♣ Pass 2♥ Pass 2♣ Pass 2♦1 Pass 2♣ Pass 2♦ Pass ? ? ? 1Fourth suit forcing ? 3. -

Franz Liszt, the Story of His Life

LISZT IN 1875. From a photograph by Kozmaia, Budapest. FEANZ LISZT THE STORY OF HIS LIFE BY RAPHAEL LEDOS DE BEAUFORT TO WHICH ARE ADDED FRANZ LISZT IN ROME BY NADINE HELBIG A LIST OF THE COMPOSER'S CHIEF WORKS A SUMMARY OF HIS COMPOSITIONS AND A LIST OF HIS NOTED PUPILS OLIVER DITSON COMl^, ''^ BOSTON , CHAS. H. DITSON & CO. LYON & JJ^ALY J. E. DITSON & CO. NEW YORK CHICAGO PHILADELPHIA All- L'5i II 10 Copyright, MDCCCLXXXVII, by OLIVER DITSON & CO. Copyright, MCMX, by OLIVER DITSON COMPANY PREFACE. The following work was suggested by the great public interest taken in the late Franz Liszt during his last visit to England. Cir- cumstances delayed its publication at the time; but the sad news of the Abbe Liszt's death having awakened anew the interest felt by our musical people in the " king of pianists," I confidently hope that all such will now find it useful. I have endeavored to furnish a concise, yet convenient, biographical sketch of the great Hungarian. Raphael Ledos de Beaufort. London, August^ 1886. CONTENTS. -'-• PAGE The Liszt family. — Adam Liszt and his wife. ... 9 II. The comet of October 12th, 1811. — First impressions. — Country Life. — Religious feelings. — The gipsies. — Franz's musical disposition 16 III. Franz's passionate love of music. — Progress on the in- strument. — Forebodings of his genius. — He becomes ill. — Recovery. — Resumes his lessons. — Impro- visation. — The foundation of his character and man- ners. — Shall he embrace the musical profession? 20 IV. Franz performs at public concerts in Oldenburg. — He plays before Prince Esterhazy in Eisenstadt.