Competing Readings of Zhang Yimou's Hero

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sight & Sound Films of 2007

Sight & Sound Films of 2007 Each year we ask a selection of our contributors - reviewers and critics from around the world - for their five films of the year. It's a very loosely policed subjective selection, based on films the writer has seen and enjoyed that year, and we don't deny them the choice of films that haven't yet reached the UK. And we don't give them much time to ponder, either - just about a week. So below you'll find the familiar and the obscure, the new and the old. From this we put together the top ten you see here. What distinguishes this particular list is that it's been drawn up from one of the best years for all-round quality I can remember. 2007 has seen some extraordinary films. So all of the films in the ten are must-sees and so are many more. Enjoy. - Nick James, Editor. 1 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days (Cristian Mungiu) 2 Inland Empire (David Lynch) 3 Zodiac (David Fincher) = 4 I’m Not There (Todd Haynes) The Lives of Others (Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck) 6 Silent Light (Carlos Reygadas) = 7 The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford (Andrew Dominik) Syndromes and a Century (Apichatpong Weerasethakul) No Country for Old Men (Ethan and Joel Coen) Eastern Promises (David Cronenberg) 1 Table of Contents – alphabetical by critic Gilbert Adair (Critic and author, UK)............................................................................................4 Kaleem Aftab (Critic, The Independent, UK)...............................................................................4 Geoff Andrew (Critic -

Recommended Films: a Preparation for a Level Film Studies

Preparation for A-Level Film Studies: First and foremost a knowledge of film is needed for this course, often in lessons, teachers will reference films other than the ones being studied. Ideally you should be watching films regularly, not just the big mainstream films, but also a range of films both old and new. We have put together a list of highly useful films to have watched. We recommend you begin watching some these, as and where you can. There are also a great many online lists of ‘greatest films of all time’, which are worth looking through. Citizen Kane: Orson Welles 1941 Arguably the greatest film ever made and often features at the top of film critic and film historian lists. Welles is also regarded as one the greatest filmmakers and in this film: he directed, wrote and starred. It pioneered numerous film making techniques and is oft parodied, it is one of the best. It’s a Wonderful Life: Frank Capra, 1946 One of my personal favourite films and one I watch every Christmas. It’s a Wonderful Life is another film which often appears high on lists of greatest films, it is a genuinely happy and uplifting film without being too sweet. James Stewart is one of the best actors of his generation and this is one of his strongest performances. Casablanca: Michael Curtiz, 1942 This is a masterclass in storytelling, staring Humphrey Bogart and Ingrid Bergman. It probably has some of the most memorable lines of dialogue for its time including, ‘here’s looking at you’ and ‘of all the gin joints in all the towns in all the world, she walks into mine’. -

Press Contacts: Michael Krause | Foundry Communications | (212) 586-7967 | [email protected]

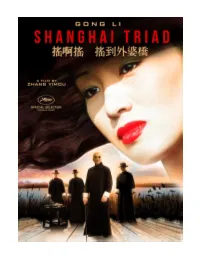

presents a film by ZHANG YIMOU starring GONG LI LI BAOTIAN LI XUEJIAN SUN CHUN WANG XIAOXIAO ————————————————————— “Visually sumptuous…unforgettable.” –New York Post “Crime drama has rarely been this gorgeously alluring – or this brutal.” –Entertainment Weekly ————————————————————— 1995 | France, China | Mandarin with English subtitles | 108 minutes 1.85:1 Widescreen | 2.0 Stereo Rated R for some language and images of violence DIGITALLY RESTORED Press Contacts: Michael Krause | Foundry Communications | (212) 586-7967 | [email protected] Film Movement Booking Contacts: Jimmy Weaver | Theatrical | (216) 704-0748 | [email protected] Maxwell Wolkin | Festivals & Non-Theatrical | (212) 941-7744 x211 | [email protected] SYNOPSIS Hired to be a servant to pampered nightclub singer and mob moll Xiao Jinbao (Gong Li), naive teenager Shuisheng (Wang Xiaoxiao) is thrust into the glamorous and deadly demimonde of 1930s Shanghai. Over the course of seven days, Shuisheng observes mounting tensions as triad boss Tang (Li Baotian) begins to suspect traitors amongst his ranks and rivals for Xiao Jinbao’s affections. STORY Shanghai, 1930. Mr. Tang (Li Boatian), the godfather of the Tang family-run Green dynasty, is the city’s overlord. Having allied himself with Chiang Kai-shek and participated in the 1927 massacre of the Communists, he controls the opium and prostitution trade. He has also acquired the services of Xiao Jinbao (Gong Li), the most beautiful singer in Shanghai. The story of Shanghai Triad is told from the point of view of a fourteen-year-old boy, Shuisheng (Wang Xiaoxiao), whose uncle has brought him into the Tang Brotherhood. His job is to attend to Xiao Jinbao. -

A Cultural Study of the Portrayal of Leading Women in Zhang Yimou Films

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Fall 2019 Unveiling Identities: A Cultural Study of the Portrayal of Leading Women in Zhang Yimou Films Patrick McGuire University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Part of the Ethnic Studies Commons, Other Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, and the Other Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation McGuire, Patrick, "Unveiling Identities: A Cultural Study of the Portrayal of Leading Women in Zhang Yimou Films" (2019). Dissertations. 1736. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/1736 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNVEILING IDENTITIES: A CULTURAL STUDY OF THE PORTRAYAL OF LEADING WOMEN IN ZHANG YIMOU FILMS by Patrick Dean McGuire A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School, the College of Arts and Sciences and the School of Communication at The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Approved by: Dr. Christopher Campbell, Committee Chair Dr. Phillip Gentile Dr. Cheryl Jenkins Dr. Vanessa Murphree Dr. Fei Xue ____________________ ____________________ ____________________ Dr. Christopher Dr. John Meyer Dr. Karen S. Coats Campbell Director of School Dean of the Graduate School Committee Chair December.2019 COPYRIGHT BY Patrick Dean McGuire 2019 Published by the Graduate School ABSTRACT It is imperative to recognize the ongoing collaborations of filmmakers from different countries. -

A Cultural Discourse Analysis to Chinese Martial Arts Movie in the Context of Glocalization: Taking Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon and Hero As Cases

Advances in Language and Literary Studies ISSN: 2203-4714 www.alls.aiac.org.au A Cultural Discourse Analysis to Chinese Martial Arts Movie in the Context of Glocalization: Taking Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon and Hero as Cases Junchen Zhang* Faculty of Humanities, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong, P.R. China Corresponding Author: Junchen Zhang, E-mail: [email protected] ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history This study is oriented to do Chinese cultural discourse analysis via examining two Chinese Received: January 14, 2019 Wu-Xia (martial arts) movies. Specifically, the study explores the construction of glocalization, Accepted: April 23, 2019 cultural hybridization and cultural discourse embedded in the two transnational Chinese martial Published: June 30, 2019 arts movies, i.e. Ang Lee’s Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000) and Zhang Yimou’s Hero Volume: 10 Issue: 3 (2002). The film product is an audiovisual representation of a certain of national culture, Advance access: May 2019 ideology and society. Chinese martial arts film is this kind of cultural product that embodies Chinese sociocultural and philosophical values. The research aims to explore the connections between filmic discourse, culture and society. A combined analytical framework that integrates Conflicts of interest: None glocalization concept, cultural hybridization and cultural discourse approach is constructed. By Funding: None comparative analysis, the main finding of the study reveals that Ang Lee’s Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000) presents a high degree of cultural globalization and hybridization, while Zhang Yimou’s Hero (2002) has relatively a low degree of cultural globalization and Key words: hybridization but embodies a high degree of Chinese locally authoritarian culture. -

Teaching Chinese Film in an Advanced Language Class

30 Guest-Edited Section—Teaching About Asia Teaching Chinese Film in an Advanced Language Class Luying Chen St. Olaf College Instructors often face a dilemma when using film in language classes. While film is appealing for the rich cultural and linguistic information it offers, finding the balance between teaching content and building language skills can present significant challenges for an instructor. Common approaches to using film in courses taught in English, such as screening one film a week, reading critical essays about the films, and class discussions and lectures, seldom offer the same benefits in a foreign language course due to the fact that students with only three years of foreign language study frequently lack the language skills necessary to discuss films in a foreign language. Yanfang Tang and Qianghai Chen, authors of the textbook Advanced Chinese: Intention, Strategy, & Communication (2005), have argued that “[n]either interpreting textual meanings nor decoding linguistic patterns leads naturally to the productive skills needed” for communicating in the target language at the advanced level.1 They further suggest that “practice, in a conscious but meaningful way is the key to successful transformation of input knowledge into productive output skills.”2 When we use films in language classes, the focus is for students to understand the textual meanings and linguistic patterns within the film, but training productive output skills in students, while fostering cultural proficiency and developing critical thinking skills, can prove to be somewhat difficult to accomplish within normal classroom time constraints. Recently published textbooks, including Readings in Contemporary Chinese Cinema (Chou, 2008, hereafter Readings)3 and Discussing Everything Chinese (Li-li Teng Foti, et al., 2007, hereafter Discussing)4, have recognized this challenge and ASIANetwork Exchange Teaching Chinese Film in an Advanced Language Class 31 experimented with different approaches to using Chinese film in advanced language classes. -

Postmen in the Mountains

POSTMEN IN THE MOUNTAINS Running time (90 Min.), "in Mandarin with English subtitles," Distributor Contact: Publicist: Ken Eisen Sharon Kitchens Shadow Distribution SKpr, LLC. P.O. Box 1246 P.O. Box 254 Waterville, ME 04903 Camden, ME 04843 ph (207) 872-5111 ph (207) 596.5686 fax (207) 872-5502 mobile (207) 542.3723 [email protected] [email protected] www.shadow distribution.com http://www.prcmovie.com/postmen/ Best Film-Montreal World Film Festival Audience Award-Maine International Film Festival Best Pictures, Best Director, Best Actor-Golden Rooster Awards (China) Best Foreign Film-Japanese Academy 1 CREDITS CREW Director: Huo Jianqi Screenplay: Si Wu Based on a Short Story by Peng Jianming Producers: Kang Jianmin, Han Sanping Cinematography: Zhao Lei Art: Song Jun Music: Wang Xiaofeng Advisors: Liu Liqing, Zheng Maoqing, Lin Mingtai, Ding Laiwen Supervisors: Ouyang Changlin, Shi Jiuhui, Li Xiaogeng Planning: Pan Yichen, Shi Dongming, Zhou Peixue Executive Producer: Li Chunhua CAST Teng Lujan.......Father Liu Ye....Son Gong Yehong....Grandmother Chen Hao....Dong Girl 2 THE STORY Father (Teng Rujun) has been a postman all his life. His job is to deliver mail to the remote mountain areas of Hunan, China by foot. He is in his late 40s. But now, poor health is forcing him to retire. He cannot trust anyone else but his son (Liu Ye) to take over the job. The morning comes that Son is ready for his first trip as a postman. It's going to be a 3-day trip., 122 kilometers, as it always is. Father cannot rest easy, ans insists that heill come along, knowing the importance of his job, and not quite able to give it up. -

Following Is a Listing of Public Relations Firms Who Have Represented Films at Previous Sundance Film Festivals

Following is a listing of public relations firms who have represented films at previous Sundance Film Festivals. This is just a sample of the firms that can help promote your film and is a good guide to start your search for representation. 11th Street Lot 11th Street Lot Marketing & PR offers strategic marketing and publicity services to independent films at every stage of release, from festival premiere to digital distribution, including traditional publicity (film reviews, regional and trade coverage, interviews and features); digital marketing (social media, email marketing, etc); and creative, custom audience-building initiatives. Contact: Lisa Trifone P: 646.926-4012 E: [email protected] www.11thstreetlot.com 42West 42West is a US entertainment public relations and consulting firm. A full service bi-coastal agency, 42West handles film release campaigns, awards campaigns, online marketing and publicity, strategic communications, personal publicity, and integrated promotions and marketing. With a presence at Sundance, Cannes, Toronto, Venice, Tribeca, SXSW, New York and Los Angeles film festivals, 42West plays a key role in supporting the sales of acquisition titles as well as launching a film through a festival publicity campaign. Past Sundance Films the company has represented include Joanna Hogg’s THE SOUVENIR (winner of World Cinema Grand Jury Prize: Dramatic), Lee Cronin’s THE HOLE IN THE GROUND, Paul Dano’s WILDLIFE, Sara Colangelo’s THE KINDERGARTEN TEACHER (winner of Director in U.S. competition), Maggie Bett’s NOVITIATE -

Culture Matters

CRF-2008-01-RFb.qxd:HRIC-Report 3/11/08 11:38 AM Page 121 CHINA RIGHTS FORUM | NO. 1, 2008 CULTURE MATTERS Hyperreal Beijing, 888 Professional baseball arose from the post-war rubble to restore Japan’s self-image. The 2002 World Cup By Ma Shengmei semifinal appearance of host South Korea led to high expectation s, though also a crushing defeat in Germany The Beijing Olympics is set to commence on August 8, in 2006. Recently, Asian exports such as the Houston 2008, promising great fanfare in an opening ceremony Rockets’ Yao Ming and the New York Yankees ’Wang orchestrated by fifth-generation filmmaker Zhang Chien-ming have become celebrities on both sides of Yimou , assisted by what the People’s Daily dubs the the Pacific, a transnational promise yet to be realized in “five-tiger generals ,” including Chinese celebrities such reverse by American export s such as Michelle Kwan. as “fireworks” artist Cai Guoqiang. 1 The number 888 is pronounced “bu, bu, bu” (as in “but”) in Cantonese and Translated back into English, however, “fu, fu, fu” is considered close to “fu, fu, fu” (as in the f-word) for sounds like the repetition of an expletive. Indeed, “prosper, prosper, prosper.” A Cantonese habit long Beijing’s official jubilation concerning 888 results in adopted by the whole country, Chinese officials deliber - the city’s underbelly, pardon the expression, getting ately chose the auspicious date of 888 (08/08/2008) for “fucked up.” The Olympic hype spells the end(game) the Games, which are intended to demonstrate China’s for Old Beijing, literally, as old hutong (alleys), prowess to the world. -

Eiko Ishioka: Blood, Sweat, and Tears-A Life of Design

Eiko Ishioka: Blood, Sweat, and Tears-A Life of Design Exhibition Guide 1 Timeless: Designing the Times The early 1960s, when Eiko Ishioka had as- building that would serve as a forefront for cul- pired to pursue a career in graphic design, was ture. As a result, she returned to the world of a time of great reform in which the importance advertising from which she began to depart of design in society had come to receive signif- from, pursuing its potential as a means of com- icant recognition. Ishioka had determined her munication that encourages people to take ac- future path due to being greatly influenced by tion. Ishioka’s campaigns promoted an inde- the internationally active designers she encoun- pendent way of life through fashion as a means tered at the 1960 World Design Conference in of self-expression, while also proposing the Tokyo while a student at Tokyo University of concept of “beauty” that emerges regardless of the Arts, especially drawing inspiration from race, gender, and wealth. Such works, through their advocacy of “design as a message to soci- their mutual interaction with the responses of ety.” Focusing on her projects in Japan, Section consumers, had essentially come to shape the 1 introduces the work of Eiko Ishioka, who had very nature and character of PARCO. attempted to seek out a distinctly personal and Ishioka from the time had been “disinter- timeless core within her practice while present- ested in creating spaces for the select and elitist ing people with new values and ways of living minority,” and thus throughout her life pursued through design. -

S2016 Film Paper 3-Director Research Project

ARTH 1112 Introduction to Film Spring 2016 Professor Sandra Cheng Atrium 631 Film Analysis Paper #3 Director Research Project DUE DATES Proposal 3/15/16 Length: 1 page SUBMIT paper copy in class Presentation 5/10/16 Length: 5-minute Powerpoint presentation and submit slide printout Paper 5/10/16 Length: 6-8 pages SUBMIT on Blackboard BEFORE MIDNIGHT 5/10/16 Choose a director from the list below. Research their career, screen at least three of your director’s films, and write a paper about the contribution their work makes and their style. Be sure to develop an analysis grounded in the formal elements of particular films. You must also depend on research, and at minimum you must quote from at least 2 scholarly and 2 non- scholarly sources. If you would like to work on another director, you must get my approval first. Strategies: A key to success in this paper is to thoroughly study your director. Look at his/her filmography, search for books, articles, and related research materials in the library. Read as many interviews and film reviews as possible. Looking for sources beyond websites will be key, as many of the best sources will still be found in books or feature articles about this person that may not be online. Pedro Almodovar Richard Linklater Wes Anderson David Lynch Michelangelo Antonioni Michael Moore Peter Bogdanovich Mira Nair John Carpenter Roman Polanski John Cassavetes Robert Rodriguez Joel and Ethan Coen George Romero Sofia Coppola Ridley Scott Federico Fellini John Singleton Howard Hawks Gus Van Sant Jim Jarmusch Wim Wenders Stanley Kubrick Lina Wertmüller Akira Kurosawa Billy Wilder Ang Lee Ed Wood Spike Lee Zhang Yimou 1. -

HERO in the WEST and EAST by FANG ZHANG a Thesis Submitted

HERO IN THE WEST AND EAST BY FANG ZHANG A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of WAKE FOREST UNIVERSITY in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of Communication May 2009 Winston-Salem, North Carolina Approved By: Peter Brunette, Ph.D., Advisor Examining Committee: Mary M. Dalton, Ph.D. Shi Yaohua, Ph.D. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This research spanned over two semesters and would not be in the current form without generous help and encouragement from many of my mentors and friends. First, my deepest appreciation, thanks and respect go to Dr. Brunette, who not only advised me on this project but throughout my graduate career at Wake Forest University. Even though we have different opinions in 2008 presidential election and political massages in Chinese films, yet we enjoy much more joyful moments of “great minds think alike,” such as sharing the excellent articles from New Yorker and Hollywood Reporter. Thank him for the trust, support and guidance throughout these years. I am looking forward to his new book on Michael Haneke. Dr. Dalton, Dr. Louden, Dr. Beasley, Dr. Giles, Dr. Hazen and Beth Hutchens from Department of Communication, they are true inspirations not only because of their work in professional careers but also how they live their lives. I am thankful for the time listening to them, working with them, and learning from them. Last year, Dr Beasley got married and Dr Krcmer had a new family member—a lovely girl, best wishes for them. This list of acknowledgements would not be complete without mentioning three of my best friends, Laura Wong, Rebecca Hao and Zhang Wei, without whose constant support and assistance, I cannot survive the hard time or get confident in facing the coming challenges.