Volcanoes, Landslides and the Hayward Fault

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Specifications

GLENDALE AVENUE RETAINING WALL SPECIFICATION NO. 21-11448-C ATTENTION 1. THE CONTRACTOR SHALL SUBMIT ALL CONTRACT DOCUMENTS INCLUDING BONDS AND INSURANCE BEFORE: July 20, 2021 2. THE CONTRACTOR SHALL COMPLY WITH THE REQUIREMENTS AND GUIDELINES OF ALL REGULATORY AGENCIES. 3. THE CITY RESERVES THE RIGHT TO REJECT ANY AND ALL PROPOSALS. 4. DURING CONSTRUCTION, THE CONTRACTOR MAY BE REQUIRED TO ATTEND WEEKLY MEETINGS AT THE ENGINEER’S OFFICE. 5. THIS PROJECT IS SUBJECT TO STATE OF CALIFORNIA SB 854 – PUBLIC WORKS REFORM 6. PROJECT INCLUDES WORK IN PRIVATE PROPERTY. WORK IN PRIVATE PROPERTY IS NOT PERMITTED UNTIL ACCESS AGREEMENTS HAVE BEEN SECURED BY THE CITY AND COPIES OF THE AGREEMENTS HAVE BEEN PROVIDED TO THE CONTRACTOR. GLENDALE AVENUE RETAINING WALL SPECIFICATION NO. 21-11448-C TENTATIVE SCHEDULE (DATES SUBJECT TO CHANGE) 1. Advertisement May 12, 2021 2. Pre-Bid Meeting None 3. Bid Opening June 8, 2021 4. Pre-Award Conference July 6, 2021 5. Council Award July 13, 2021 6. Contract Documents Due July 20, 2021 7. Contract Award August 17, 2021 (Notice to Proceed) 8. Start Construction September 8, 2021 9. Complete Construction December 20, 2021 GLENDALE AVENUE RETAINING WALL SPECIFICATION NO. 21-11448-C TABLE OF CONTENTS PART A - BIDDING CONTRACTUAL DOCUMENTS NOTICE TO BIDDERS A1 – A4 BIDDER’S AND CONTRACTOR’S CHECK LIST A5 BIDDER’S PROPOSAL A6 – A10 EXPERIENCE AND FINANCIAL QUALIFICATIONS A11 TAXPAYER IDENTIFICATION REPORT A12 MEMORANDUM OF UNDERSTANDING A13 WORKFORCE COMPOSITION OCCUPATIONAL CATEGORIES A14 WORKFORCE COMPOSITION -

Oral History Center University of California the Bancroft Library Berkeley, California

Oral History Center University of California The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California Dorothy Walker Interviews conducted by Shanna Farrell in 2014 and 2015 Copyright © 2015 by The Regents of the University of California ii Since 1954 the Oral History Center of the Bancroft Library, formerly the Regional Oral History Office, has been interviewing leading participants in or well-placed witnesses to major events in the development of Northern California, the West, and the nation. Oral History is a method of collecting historical information through tape-recorded interviews between a narrator with firsthand knowledge of historically significant events and a well-informed interviewer, with the goal of preserving substantive additions to the historical record. The tape recording is transcribed, lightly edited for continuity and clarity, and reviewed by the interviewee. The corrected manuscript is bound with photographs and illustrative materials and placed in The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, and in other research collections for scholarly use. Because it is primary material, oral history is not intended to present the final, verified, or complete narrative of events. It is a spoken account, offered by the interviewee in response to questioning, and as such it is reflective, partisan, deeply involved, and irreplaceable. ********************************* All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between The Regents of the University of California and June 4, 2015. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. Excerpts up to 1000 words from this interview may be quoted for publication without seeking permission as long as the use is non-commercial and properly cited. -

Shattuck Avenue Commercial Corridor Historic Context and Survey

Shattuck Avenue Commercial Corridor Historic Context and Survey Prepared for: City of Berkeley Department of Planning and Development City of Berkeley 2120 Milvia St. Berkeley, CA 94704 Attn: Sally Zarnowitz, Principal Planner Secretary to the Landmarks Preservation Commission 05.28.2015 FINAL DRAFT (Revised 08.26.2015) ARCHIVES & ARCHITECTURE, LLC PO Box 1332 San José, CA 95109-1332 http://www.archivesandarchitecture.com Shattuck Avenue Commercial Corridor Historic Context and Survey ACKNOWLEDGMENT The activity which is the subject of this historic context has been financed in part with Federal funds from the National Park Service, Department of the Interior, through the California Office of Historic Preservation. However, the contents and opinions do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of the Interior or the California Office of Historic Preservation, nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation by the Department of the Interior or the California Office of Historic Preservation. Regulations of the U.S. Department of the Interior strictly prohibit unlawful discrimination in departmental federally‐assisted programs on the basis of race, color, sex, age, disability, or national origin. Any person who believes he or she has been discriminated against in any program, activity, or facility operated by a recipient of Federal assistance should write to: Director, Equal Opportunity Program U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service P.O. Box 37127 Washington, DC 20013‐7127 Cover image: USGS Aerial excerpt, Microsoft Corporation ARCHIVES & ARCHITECTURE 2 Shattuck Avenue Commercial Corridor Historic Context and Survey Table of Contents Table of Contents Table of Contents .......................................................................................................................... -

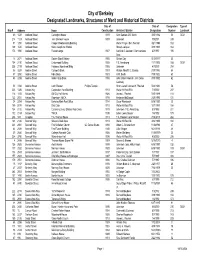

COB Landmarks Updated April 2015

City of Berkeley Designated Landmarks Date of Number Street Name1 Name2 Construction Architect Designation Type DEMO Binder Number Note Joseph McVay Oceanview Sisterna 814 Addison Street House Historic District 1888 Roarke 3/1/2004 CBDist 267 Joseph and Wilson Oceanview Sisterna 816 Addison Street McVay House Historic District 1892 Unknown 3/1/2004 CBDist 267 Carrington House, Seth Babson & R. 1029 Addison Street Bartine 1893 Wenk 3/15/1982 SOM 54 1124 Addison Street John Brennan House 1891 Unknown 7/9/2001 LM 237 Cooper Woodworking Walter Crapo / Ben 1250 Addison Street Building 1912 Pearson 4/21/1986 LM 100 Saint Joseph the 1640 Addison Street Worker 0 Shea & Lofquist 3/18/1991 LM partial 160 Sanford G. Jackson / 1900 Addison Street Framat Lodge 1927 Sommarstrom Bros. 4/7/1997 LM 193 The John Boyd 1915 Addison Street House 1893 Unknown 1/5/2012 SOM 310 Golden Sheaf 2071 Addison Street Bakery 1905 Clinton Day 12/19/1977 LM 21 2110 Addison Street Underwood Building 1905 F.E. Armstrong 11/1/1993 SOM 178 Heywood Apartment 2119 Addison Street Bldg 1906 Unknown 4/7/2003 LM 251 Frederick H. Dakin Walter H. Ratcliff & 2750 Adeline Street Warehouse 1906 George T. Plowman 8/9/2004 LM 273 The Hoffman 2988 Adeline Street Building 1905 Henry Ahnefeld 7/6/2006 SOM 286 The William Clephane Corner 3027 Adeline Street Store 1905 C.M. Cook 9/7/2006 LM 290 William Wharff / C. 3228 Adeline Street Carlson's Block 1903 Ekman 7/19/1982 LM 64 3250 Adeline Street India Block 1903 A.W. -

The Baha Newsletter No

BERKELEY ARCHITECTURAL HERITAGE ASSOCIATION THE BAHA NEWSLETTER NO. 146 SUMMER 2015 ANNUAL PRESERVATION AWARDS NUMBER THE BAHA NEWSLETTER NO. 146 SUMMER 2015 Palace of Fine Arts C O N T E N T S Festival Hall Gifts to BAHA page 2 Elmwood House Tour—special to BAHA page 12 Message from the President page 3 Latest Landmark page 14 Preservation Award Winners page 5 Member News page 15 Walter W. Ratcliff, In Memoriam page 11 Fall Lecture Series page 16 Cover: Church of the Good Shepherd. John WEBSITES YOU SHOULD KNOW McBride, 2015 (Photoshop by Kathleen Burch). • BAHA’s website in- • BAHA maintains a • BAHA is on Top left: Bernard Maybeck’s Palace of Fine Arts cludes upcoming events, a blog where notices facebook: face- from a souvenir view book, 1915. list of Berkeley land- of immediate interest book.com/berke- Top right: Buffington family in front of Festival marks, illustrated essays, are posted: baha- ley.architectural. Hall, 1915. Both courtesy Anthony Bruce. and more: news.blogspot.com heritage?ref=hl berkeleyheritage.com BOARD OF DIRECTORS John McBride, President Sally Sachs, Thanks from BAHA Vice-President Candice Basham and Louise Hendry gave BAHA their copies of old house tour Carrie Olson, Corporate Secretary guides. From Richard B. Silver, a former owner of City of Berkeley Landmark, Jane McKinne-Mayer, Fox Court, came a gift of blueprints and original drawings (including a color ren- Recording Secretary dering) from the Fox Brothers office, and one of the original pieces of furniture Steven Finacom, Corresponding Secretary from the complex, a chair with a rawhide seat. -

Shattuck Avenue Commercial Corridor Historic Context and Survey

Shattuck Avenue Commercial Corridor Historic Context and Survey Prepared for: City of Berkeley Department of Planning and Development City of Berkeley 2120 Milvia St. Berkeley, CA 94704 Attn: Sally Zarnowitz, Principal Planner Secretary to the Landmarks Preservation Commission 05.28.2015 FINAL DRAFT ARCHIVES & ARCHITECTURE, LLC PO Box 1332 San José, CA 95109-1332 http://www.archivesandarchitecture.com Shattuck Avenue ACKNOWLEDGMENT The activity which is the subject of this historic context has been financed in part with Federal funds from the National Park Service, Department of the Interior, through the California Office of Historic Preservation. However, the contents and opinions do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of the Interior or the California Office of Historic Preservation, nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation by the Department of the Interior or the California Office of Historic Preservation. Regulations of the U.S. Department of the Interior strictly prohibit unlawful discrimination in departmental federally‐assisted programs on the basis of race, color, sex, age, disability, or national origin. Any person who believes he or she has been discriminated against in any program, activity, or facility operated by a recipient of Federal assistance should write to: Director, Equal Opportunity Program U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service P.O. Box 37127 Washington, DC 20013‐7127 Cover image: USGS Aerial excerpt, Microsoft Corporation -

California Ephemera Collection CA EPH

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt1v19r8pg No online items California Ephemera Collection CA EPH Finding aid prepared by Finding aid prepared by California Historical Society staff. California Historical Society 678 Mission Street San Francisco, CA, 94105-4014 (415) 357-1848 [email protected] 2011 California Ephemera Collection CA CA EPH 1 EPH Title: California Ephemera Collection Date (inclusive): 1841-2001 Date (bulk): 1880-1980 Collection Identifier: CA EPH Extent: 140.0 boxes (68 linear feet) Contributing Institution: California Historical Society 678 Mission Street San Francisco, CA 94105 415-357-1848 [email protected] URL: http://www.californiahistoricalsociety.org Location of Materials: Collection is stored onsite. Language of Materials: Collection materials are in English. Abstract: The collection consists of a wide range of ephemera pertaining to the state of California and each of its constituent counties, excluding the City and County of San Francisco. Dating from 1841 to 2001, the collection includes ephemera created by or related to churches; civic associations and activist groups; clubs and societies, especially fraternal organizations; labor unions; auditoriums and theaters; historic buildings, landmarks, and museums; hotels and resorts; festivals and fairs; sporting events; hospitals, sanatoriums, prisons, and orphanages; schools, colleges, and universities; government agencies; elections, ballot measures, and political parties; infrastructure and transit systems; geographic features; and other subjects. Types of ephemera include: advertisements; brochures; folders; programs; leaflets; pamphlets; announcements; guides; maps; tickets; invitations; newsletters; constitutions and bylaws; surveys and reports; directories and listings; fliers; badges and ribbons; ballots; dance cards; invitations; catalogues; report cards and syllabi; journals and journal articles; and newspaper clippings. -

COB Landmarks1 Page 1

COB_Landmarks1 Date of Number Street Name1 Name2 Construction Architect Designation Type DEMO 814 Addison Street Joseph McVay House Oceanview Sisterna Historic District 1888 Roarke 3/1/2004 CBDist 816 Addison Street Joseph and Wilson McVay House Oceanview Sisterna Historic District 1892 3/1/2004 CBDist 1029 Addison Street Carrington House, Bartine 1893 Seth Babson & R. Wenk 3/15/1982 SOM 1124 Addison Street John Brennan House 1891 Unknown 7/9/2001 LM 1250 Addison Street Cooper Woodworking Building 0 Walter Crapo / Ben Pearson 4/21/1986 LM 1640 Addison Street Saint Joseph the Worker 0 Shea & Lofquist 3/18/1991 LM partial 1900 Addison Street Framat Lodge 1927 Sanford G. Jackson / Sommarstrom Bros. 4/7/1997 LM 2071 Addison Street Golden Sheaf Bakery 1905 Clinton Day 10/17/1977 LM 2110 Addison Street Underwood Building 1905 F.E. Armstrong 11/1/1993 SOM 2119 Addison Street Heywood Apartment Bldg 1906 Unknown 4/7/2003 LM 3027 AdelineStreet The William Clephane Corner Store 1905 C.M. Cook 9/7/2006 LM 2750 Adeline Street Frederick H. Dakin Warehouse 1906 Walter H. Ratcliff & George T. Plowman 8/9/2004 LM 2988 Adeline Street The Hoffman Building 1905 Henry Ahnefeld 7/6/2006 SOM 3228 Adeline Street Carlson's Block 1903 William Wharff / C. Ekman 7/19/1982 LM 3250 Adeline Street India Block 1903 A.W. Smith 7/19/1982 LM 3286 Adeline Street Wells Fargo Bank 1906 John Galen Howard / John Debo Galloway 7/19/1982 LM 3332 Adeline Street Lorin Theater Phillips Temple 0 Hiram Lovell / James W. Plachek 5/24/1982 LM 1920 Allston Way Berkeley High School Old Gym and Pool 1922 William C. -

City of Berkeley Designated Landmarks, Structures of Merit And

City of Berkeley Designated Landmarks, Structures of Merit and Historical Districts Date of Date of Designation Type of Map # Address Name Construction Architect / Builder Designation Number Landmark 49 1029 Addison Street Carrington House 1893 Seth Babson & R. Wenk 3/15/1982 53 SOM 214 1124 Addison Street John Brennan House 1891 Unknown 7/9/2001 240 97 1250 Addison Street Cooper Woodworking Building Walter Crapo / Ben Pearson 4/21/1986 102 149 1640 Addison Street Saint Joseph the Worker Shea & Lofquist 3/18/1991 164 176 1900 Addison Street Framat Lodge 1927 Sanford G. Jackson / Sommarstrom 4/7/1997 195 Bros. 18 2071 Addison Street Golden Sheaf Bakery 1905 Clinton Day 10/17/1977 20 164 2110 Addison Street Underwood Building 1905 F.E. Armstrong 11/1/1993 185 SOM 228 2119 Addison Street Heywood Apartment Bldg 1906 Unknown 4/7/2003 254 56 3228 Adeline Street Carlson's Block 1903 William Wharff / C. Ekman 7/19/1982 64 57 3250 Adeline Street India Block 1903 A.W. Smith 7/19/1982 63 58 3286 Adeline Street Wells Fargo Bank 1906 John Galen Howard / John Debo 7/19/1982 62 Galloway 53 3332 Adeline Street Lorin Theater Phillips Temple Hiram Lovell / James W. Plachek 5/24/1982 58 223 1326 Allston Way Corporation Yard Building 1913 Walter H. Ratcliff Jr. 7/1/2002 247 116 1835 Allston Way Old City Hall Annex 1926 James L. Plachek 5/15/1989 118 122 2001 Allston Way Downtown YMCA 1910 Benjamin McDougall 2/20/1990 131 34 2004 Allston Way Berkeley Main Post Office 1914 Oscar Wenderoth 6/16/1980 38 150 2018 Allston Way Elks Club 1913 Walter H. -

Berkeley Unified School District Office of the Superintendent 2134 Martin Luther King Jr

Berkeley Unified School District Office of the Superintendent 2134 Martin Luther King Jr. Way Berkeley, CA 94704-1180 Phone: (510) 644-6206 Fax: (510) 540-5358 BOARD OF EDUCATION – MEETING AGENDA* Wednesday, March 23, 2011 Call to Order The Presiding Officer will call the Meeting to Order at 6:00 p.m., recess to Closed Session, and begin regular Board Meeting agenda by 7:30 p.m. Roll Call Members Present: Beatriz Leyva-Cutler, President John T. Selawsky, Vice President/Clerk Karen Hemphill, Director Leah Wilson, Director Josh Daniels, Director Lias Djili - Student Director Administration: Superintendent William Huyett, Secretary Javetta Cleveland, Deputy Superintendent Neil Smith, Assistant Superintendent of Educational Services Delia Ruiz, Assistant Superintendent of Human Resources The Board will recess into closed session under the authority of the Brown Act (including but not limited to Government Code section 54954.5, 54956.8, 54956.9, 54957, 54957.6, as well as Education Code section 35146). Under Government Code section 54954.3, members of the public may address the board on an item on the closed session agenda, before closed session. a) Conference with Legal Counsel – Existing Litigation/Anticipated b) Consideration of Student Expulsions Expulsion: Student Case No. 1011-19 -082393 Readmissions: Student Case No. OD1011-28 -032296 Student Case No. 0910-19-020795 c) Collective Bargaining d) Public Employee Discipline/Dismissal /Release/Evaluation f) Liability Claims g) Property Acquisition & Disposal - Hillside h) Superintendent’s Evaluation * Board agenda posted on District website: www.berkeley.k12.ca.us ** The Student Director does not attend Closed Session Page 1 of 7 The Berkeley Unified School District intends to provide reasonable accommodations in accordance with the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990. -

ATTACHMENT 5 ZAB 03-14-19 Page 1 of 69

ATTACHMENT 5 ZAB 03-14-19 Page 1 of 69 August 19, 2018 To: City of Berkeley Department of Planning and Development Attention: Allison Riemer, Assistant Planner Re: Objection to Project and AUP Application at 1991 Marin Avenue (APN: 061 257400200, Permit: ZP2018-0166) From: Joe DiStefano and Amy Buege, Homeowners 1972 Los Angeles Ave Berkeley, CA 94707 To: Allison Reimer We are writing to strongly object to the application for a new accessory dwelling unit (ADU) at 1991 Marin Ave. We (my wife and I, and our two young children) are the direct neighbors of this property, which is located in the hillside district on a very atypical parcel layout just below the Marin Circle. While we support the development of ADUs in the City, and even support an ADU on this specific parcel, we strongly object to the plan as designed and filed before the city on August 17, 2018. We were deeply surprised to hear about this project for the first time less than two weeks ago when the applicants came to our house to show us the plan and get our signature on the AUP application. Despite being deeply impacted by the project, we and other neighbors were never consulted about the project, asked for opinions or suggestions, or otherwise engaged at anytime prior. This is a highly atypical parcel and project. The plan envisions a new residential unit on a thru-lot facing a different street (Los Angeles Avenue) than the main house on the property (which fronts Marin Ave). The impact of the project, which is unfortunately amplified by the specific design proposal, focuses the impact of the new unit on the front of adjacent homes and parcels.