Newburgh Habitat Summary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inspiring People to Stop Water Pollution Through Community Science

Inspiring People to Stop Water Pollution through Community Science Dan Shapley Water Quality Program Manager Mohawk Watershed Symposium March 20, 2015 Inspiring Through Citizen Science • Our Water Quality Monitoring Program • Grassroots Inspiration 74 Sample sites 155 miles since 2008 Dr. Gregory O’Mullan Dr. Andrew Juhl Community Partners • Catskill Creek Watershed Awareness Project • Gardiner Environmental Conservation Commission • Montgomery Conservation Advisory Council • New York City Water Trail Association • Quassaick Creek Watershed Alliance • Rochester Environmental Conservation Commission • Rosendale Commission for Conservation of the Environment • Sparkill Creek Watershed Alliance • Wawarsing Environmental Conservation Commission Citizen Studies 8 Projects Catskill Creek 19 sites on 45 miles 149 Sites 212 Miles Esopus Creek 10 sites on 25 miles Rondout Creek Esopus Creek 17 sites on 43 miles Wallkill River 21 sites on 64 miles Rondout Creek Pocantico River 13 sites on 10 miles Sparkill Creek 16 sites on 8 miles Wallkill River Quassaick Creek Pocantico River 14 sites on 17 miles NYC Waterfront Sparkill Creek 39 sites in NYC, NJ & Yonkers Citizen Non-Tidal Tributary Sampling Sites % Samples Failing EPA-Recommended Beach Advisory Value (2012-2013) Catskill Creek 33% 67% Esopus Creek 31% 69% Rondout Creek 66% 34% Wallkill River 86% 14% Pocantico River 80% 20% Sparkill Creek 89% 11% Hudson River 23% 77% (2008-2013) % Beach Advisory % Acceptable Pollution Enforcement East River Illegal sewage discharge stopped in Hallets Cove Catskill -

Town of Chester CPP Plan 3-26-19

Community Preservation Plan Town of Chester, NY March 26, 2019 Committee Draft Prepared by the Town of Chester Community Preservation Plan Committee Prepared with technical assistance from: Planit Main Street, Inc. Preface The Town of Chester has long recognized that community planning is an ongoing process. In 2015, the Town Board adopted a Comprehensive Plan, which was an update of its 2003 Comprehensive Plan. The 2015 Comprehensive Plan recommended additional actions, plans and detailed studies to pursue the recommendations of the Comprehensive Plan. Among these were additional measures to protect natural resources, agricultural resources and open space. In September 2017, the Town Board appointed a Community Preservation Plan Committee (CPPC) to guide undertake the creation of the Town’s first Community Preservation Plan. This Community Preservation Plan is not a new departure - rather it incorporates and builds upon the recommendations of the Town’s adopted 2015 Comprehensive Plan and its existing land use regulations. i Acknowledgements The 2017 Community Preservation Plan (CPP) Steering Committee acknowledges the extraordinary work of the 2015 Comprehensive Plan Committee in creating the Town’s 2015 Comprehensive Plan. Chester Town Board Hon. Alex Jamieson, Supervisor Robert Valentine - Deputy Supervisor Brendan W. Medican - Councilman Cynthia Smith - Councilwomen Ryan C. Wensley – Councilman Linda Zappala, Town Clerk Clifton Patrick, Town Historian Town of Chester Community Preservation Plan Committee (CPPC) NAME TITLE Donald Serotta Chairman Suzanne Bellanich Member Tim Diltz Member Richard Logothetis Member Tracy Schuh Member Robert Valentine Member Consultant Alan J. Sorensen, AICP, Planit Main Street, Inc. ii Contents 1.0 Introduction, Purpose and Summary .............................................................................................. 4 2.0 Community Preservation Target Areas, Projects, Parcels and Priorities ..................................... -

Report: 13% of Hudson Valley Bridges in Poor Condition

Report: 13% of Hudson Valley bridges in poor condition FRONT PAGE lower-weight vehicles, that can have an impact on everyone from emergency responders to school buses, commercial vehicles and farm equipment, who will all need to make longer trips to get The Mill Street bridge, over Quassaick Creek in where they need to Newburgh/New Windsor, is the second-worst go. ranked bridge among the 25 cited in the Hudson Valley as poor/structurally deficient [KEELY “Good MARSH/FOR THE TIMES HERALD-RECORD] infrastructure is also the cornerstone of By Michael Randall bringing in good Times Herald-Record jobs,” said Mike GOSHEN – A new report from a nonprofit group Oates, president that researches and evaluates the conditions of and CEO of Hudson the roads we travel on says 13 percent of the Valley Economic Hudson Valley’s bridges are in poor, structurally Development deficient condition. Corporation. “I hope Another 64 percent are in fair condition, while this (report) leads to only 23 percent are in good condition. action, so we’re not At a news conference Tuesday at the Orange at a competitive County Chamber of Commerce office, Carolyn disadvantage with Bonifas Kelly, associate director of research for other states.” the nonprofit, The Road Information Project New York ranks (TRIP), said those structurally deficient bridges 12th among the 50 6. Pine Hill Road over the Thruway, Woodbury carry almost 2.6 million vehicles per day. states, with 10 percent of its bridges in poor or 12. South Street over Wawayanda Creek, Warwick Her study included 2,551 bridges in Orange, structurally deficient condition. -

Connect Mid-Hudson Regional Transit Study

CONNECT MID-HUDSON Transit Study Final Report | January 2021 1 2 CONTENTS 1. Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................................................. 4 2. Service Overview ...................................................................................................................................................................... 5 2.1. COVID-19 ...................................................................................................................................................................... 9 2.2. Public Survey ................................................................................................................................................................ 9 2.2.1. Dutchess County ............................................................................................................................................10 2.2.2. Orange County ................................................................................................................................................11 2.2.3. Ulster County ..................................................................................................................................................11 3. Transit Market Assessment and Gaps Analsysis ..................................................................................................................12 3.1. Population Density .....................................................................................................................................................12 -

Hudson River Estuary Program Report on 15 Years of Progress Helping People Enjoy, Protect and Revitalize the Hudson River Estuary and Its Valley

Hudson River Estuary Program Report on 15 Years of Progress Helping people enjoy, protect and revitalize the Hudson River Estuary and its Valley Clean Water * Habitat * River Access * Climate Change * Scenery NYS Department of Environmental Conservation in partnership with: Andrew M. Cuomo, Governor NYS Department of State Joseph Martens, Commissioner NYS Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation NYS Department of Health March 2011 NYS Office of General Services Hudson River Valley Greenway US Environmental Protection Agency National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration US Department of Interior Dear Friend of the Hudson: Since 1987, the Hudson River Estuary Program (HREP) has been changing the way New York State manages the river and the valley environment. Significant public participation guided the development of our first Action Agenda, adopted in 1996, which enabled a new, comprehensive approach. Now 15 years later, we are: • Coordinating among local, state and federal agencies to achieve shared goals; • Using science and technology to solve river problems; • Building the capacity for local stewardship of natural resources; • Helping people discover the river; and • Building a network for regional cooperation. This report is a snapshot of what the Estuary Program and its partners have been doing for the last 15 years. It shows how we are supporting the quality of life of people and improving the future health and vitality of the natural resources of the Hudson River and its valley. The report begins with the four “Estuary Action Agendas” that have been issued and implemented since 1996. Built on sound science and extensive public input, these Action Agendas have set clear goals and targets for progress that can be objectively measured. -

Coastal Fish and Wildlife Rating Form

COASTAL FISH AND WILDLIFE RATING FORM Name of area: Moodna Creek Designated: November 15, 1987 Revised: August 15, 2012 County: Orange Town(s): Cornwall, New Windsor 7.5’ Quadrangles: Cornwall, NY Assessment Criteria Score Ecosystem Rarity (ER) -- the uniqueness of the plant and animal community in the area and the physical, structural and chemical features supporting this community. ER Assessment - A major freshwater tributaries of the lower Hudson River that is accessible 16 to coastal migratory fishes; includes the largest tidal marsh in Orange County. Species Vulnerability (SV) – the degree of vulnerability throughout its range in New York State of a species residing in the ecosystem or utilizing the ecosystem for its survival. SV Assessment –Least bittern (T), bald eagle (T), American bittern (SC) 41.5 Additive division: 25 + 25/2 + 16/4 = Human Use (HU) -- the conduct of significant, demonstrable commercial, recreational, or educational wildlife-related human use, either consumptive or non-consumptive, in the area or directly dependent upon the area. HU Assessment -- Recreational fishing opportunities attract many Orange County anglers, 4 paddlers, and nature observers to the area. Population Level (PL) – the concentration of a species in the area during its normal, recurring period of occurrence, regardless of the length of that period of occurrence. PL Assessment -- Concentrations of various wetland wildlife species and coastal migratory 9 fishes in this area are unusual in Orange County and the Hudson Valley Region. Replaceability (R) – ability to replace the area, either on or off site, with an equivalent replacement for the same fish and wildlife and uses of those same fish and wildlife, for the same users of those fish and wildlife. -

LOCAL IMPACTS and COSTS Exhibit IX. A.2.B Traffic and Roadway

LOCAL IMPACTS AND COSTS Exhibit IX. A.2.b The proposed Resorts World Hudson Valley is a mixed use development that will incorporate a 600‐room hotel with a full‐service gaming facility and a conference center, along with associated, complementary amenities on an approximate 373‐acre site. Potential impacts include those to traffic and noise, watershed impacts from stormwater and wastewater discharge, and hydrologic impacts to surface waters and wetlands. The design for Resorts World Hudson Valley has been developed in conjunction with LEED® measures to minimize impacts to the greatest extent possible. Where impacts cannot be avoided, RW Orange County LLC has developed a cohesive mitigation strategy as detailed in Exhibit IX.A.3 Mitigation of Impact to Host Municipality and Nearby Municipalities. Traffic and Roadway Infrastructure Preliminary Transportation Demand Impacts Development of the proposed Resorts World Hudson Valley would generate substantial numbers of new vehicular trips by auto, taxi and bus on the roadway system providing access to the project site. The majority of these trips (approximately 90 percent) would arrive and depart via I‐84, with Route 17K, Route 747 and Route 207 providing local access. Most vehicles destined to/from I‐84 would use the I‐84/Route 747 interchange located immediately to the southeast of the project site which was designed to accommodate future demand from expanded use of the nearby Stewart International Airport. As this airport demand has not been realized, the I‐84/Route 747 interchange typically functions with available capacity during peak periods. A new signalized intersection on Route 17K and a new roundabout on Route 747 would provide access to the proposed project’s internal roadway system. -

HUDSON RIVER RISING Riverkeeper Leads a Growing Movement to Protect the Hudson

Confronting climate | Restoring nature | Building resilience annual journal HUDSON RIVER RISING Riverkeeper leads a growing movement to protect the Hudson. Its power is unstoppable. RIVERKEEPER JOURNAL 01 Time and again, the public rises to speak for a voiceless Hudson. While challenges mount, our voices grow stronger. 02 RIVERKEEPER JOURNAL PRESIDENT'S LETTER Faith and action It’s all too easy to feel hopeless these days, lish over forty new tanker and barge anchorages allowing storage of crude when you think about the threat posed by climate oil right on the Hudson, Riverkeeper is working with local partners to stop disruption and the federal government’s all-out another potentially disastrous plan to build enormous storm surge barriers war on basic clean water and habitat protection at the entrance to the Hudson Estuary. Instead, we and our partners are laws. Yet, Riverkeeper believes that a better fighting for real-world, comprehensive and community-driven solutions future remains ours for the taking. to coastal flooding risks. We think it makes perfect sense to feel hope- History was made, here on the Hudson. Groundbreaking legal pro- ful, given New York’s new best-in-the-nation tections were born here, over half a century ago, when earlier waves of climate legislation and its record levels of spend- activists rose to protect the Adirondacks, the Palisades and Storm King ing on clean water (which increased by another Mountain and restore our imperiled fish and wildlife. These founders had $500 million in April). This year, The Empire State also banned river-foul- no playbook and certainly no guarantee of success. -

Army Corps of Engineers Response Document Draft

3.0 ORANGE COUNTY Orange County has experienced numerous water resource problems along the main stem and the associated tributaries of the Moodna Creek and the Ramapo River that are typically affected by flooding during heavy rain events over the past several years including streambank erosion, agradation, sedimentation, deposition, blockages, environmental degradation, water quality and especially flooding. However, since October 2005, the flooding issues have severely increased and flooding continues during storm events that may or may not be considered significant. Areas affected as a result of creek flows are documented in the attached trip reports (Appendix D). Throughout the Orange County watershed, site visits confirmed opportunities to stabilize the eroding or threatened banks restore the riparian habitat while controlling sediment transport and improving water quality, and balance the flow regime. If the local municipalities choose to request Federal involvement, there are several options, depending on their budget, desired timeframe and intended results. The most viable options include a specifically authorized watershed study or program, or an emergency streambank protection project (Section 14 of the Continuing Authorities Program), or pursing a Continuing Authorities Program study for Flood Risk Management or Aquatic Ecosystem Restoration (Section 205 and Section 206 of the Continuing Authorities Program, respectively). Limited Federal involvement could also be provided in the form of the Planning Assistance to States or Support for Others programs provide assistance and limited funds outside of traditional Corps authorities. A watershed study focusing on restoration of the Moodna Creek, Otter Creek, Ramapo River and their associated tributaries could address various problems using a systematic approach. -

Waterbody Classifications, Streams Based on Waterbody Classifications

Waterbody Classifications, Streams Based on Waterbody Classifications Waterbody Type Segment ID Waterbody Index Number (WIN) Streams 0202-0047 Pa-63-30 Streams 0202-0048 Pa-63-33 Streams 0801-0419 Ont 19- 94- 1-P922- Streams 0201-0034 Pa-53-21 Streams 0801-0422 Ont 19- 98 Streams 0801-0423 Ont 19- 99 Streams 0801-0424 Ont 19-103 Streams 0801-0429 Ont 19-104- 3 Streams 0801-0442 Ont 19-105 thru 112 Streams 0801-0445 Ont 19-114 Streams 0801-0447 Ont 19-119 Streams 0801-0452 Ont 19-P1007- Streams 1001-0017 C- 86 Streams 1001-0018 C- 5 thru 13 Streams 1001-0019 C- 14 Streams 1001-0022 C- 57 thru 95 (selected) Streams 1001-0023 C- 73 Streams 1001-0024 C- 80 Streams 1001-0025 C- 86-3 Streams 1001-0026 C- 86-5 Page 1 of 464 09/28/2021 Waterbody Classifications, Streams Based on Waterbody Classifications Name Description Clear Creek and tribs entire stream and tribs Mud Creek and tribs entire stream and tribs Tribs to Long Lake total length of all tribs to lake Little Valley Creek, Upper, and tribs stream and tribs, above Elkdale Kents Creek and tribs entire stream and tribs Crystal Creek, Upper, and tribs stream and tribs, above Forestport Alder Creek and tribs entire stream and tribs Bear Creek and tribs entire stream and tribs Minor Tribs to Kayuta Lake total length of select tribs to the lake Little Black Creek, Upper, and tribs stream and tribs, above Wheelertown Twin Lakes Stream and tribs entire stream and tribs Tribs to North Lake total length of all tribs to lake Mill Brook and minor tribs entire stream and selected tribs Riley Brook -

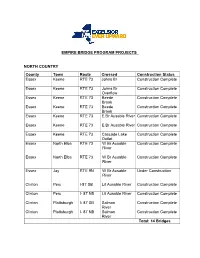

Empire Bridge Program Projects North Country

EMPIRE BRIDGE PROGRAM PROJECTS NORTH COUNTRY County Town Route Crossed Construction Status Essex Keene RTE 73 Johns Br Construction Complete Essex Keene RTE 73 Johns Br Construction Complete Overflow Essex Keene RTE 73 Beede Construction Complete Brook Essex Keene RTE 73 Beede Construction Complete Brook Essex Keene RTE 73 E Br Ausable River Construction Complete Essex Keene RTE 73 E Br Ausable River Construction Complete Essex Keene RTE 73 Cascade Lake Construction Complete Outlet Essex North Elba RTE 73 W Br Ausable Construction Complete River Essex North Elba RTE 73 W Br Ausable Construction Complete River Essex Jay RTE 9N W Br Ausable Under Construction River Clinton Peru I-87 SB Lit Ausable River Construction Complete Clinton Peru I- 87 NB Lit Ausable River Construction Complete Clinton Plattsburgh I- 87 SB Salmon Construction Complete River Clinton Plattsburgh I- 87 NB Salmon Construction Complete River Total: 14 Bridges CAPITAL DISTRICT County Town Route Crossed Construction Status Warren Thurman Rte 28 Hudson River Construction Complete Washington Hudson Falls Rte 196 Glens Falls Construction Complete Feeder Canal Washington Hudson Falls Rte 4 Glens Falls Construction Complete Feeder Saratoga Malta Rte 9 Kayaderosseras Construction Complete Creek Saratoga Greenfield Rte 9n Kayaderosseras Construction Complete Creek Rensselaer Nassau Rte 20 Kinderhook Creek Construction Complete Rensselaer Nassau Rte 20 Kinderhook Creek Construction Complete Rensselaer Nassau Rte 20 Kinderhook Creek Construction Complete Rensselaer Hoosick Rte -

2008Brochure No Ads.Indd

Supervisors Message Message Supervisor’s During the past couple of years the Town of Newburgh Department of Parks, Recreation and Conservation has been upgrading the park and trail areas at Chadwick Lake. The playground area has been expanded, an all-purpose playing fi eld has been created and new-lighted basketball courts have been installed. Along with these physi- cal improvements the department has added programs and trips to accommodate all age and interest groups. If you haven’t been to Chadwick Lake Park lately, stop by and see what you’ve been missing. Enjoy a walk on the trail or a lazy day of fi shing from shore or from one of our many rental boats. You may want to rent one of our three pavilions for your next outdoor party or just bring the children to the playground and enjoy the view of the lake. The entire Town Board, employees and volunteers of the Town of Newburgh look forward to assisting you and your families, so that you may maximize the benefi ts of the programs and activities offered by our Recreation Department. We all look forward to seeing you this coming year. Best wishes for a happy and active 2008. Sincerely, Wayne C. Booth Wayne C. Booth Supervisor Recreation Clerk Here to Serve You… Town of Newburgh Amanda Weidkam Recreation Senior Citizen Activity Leader Debbie DeAgostine Wayne C. Booth, Supervisor Department -Transportation- At Your Service John Grimm, Dispatcher *Council persons* 311 Rte 32 - Newburgh NY 12550 Drivers: (845)564-7815 * Fax # 564-7827 Faye Mcintosh Derek Benedict Gil Piaquadio www.townofnewburgh.org