Edinburgh Research Explorer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Case Study on Dhallywood Film Industry, Bangladesh

Research Article, ISSN 2304-2613 (Print); ISSN 2305-8730 (Online) Determinants of Watching a Film: A Case Study on Dhallywood Film Industry, Bangladesh Mst. Farjana Easmin1, Afjal Hossain2*, Anup Kumar Mandal3 1Lecturer, Department of History, Shahid Ziaur Rahman Degree College, Shaheberhat, Barisal, BANGLADESH 2Associate Professor, Department of Marketing, Patuakhali Science and Technology University, Dumki, Patuakhali-8602, BANGLADESH 3Assistant Professor, Department of Economics and Sociology, Patuakhali Science and Technology University, Dumki, Patuakhali-8602, BANGLADESH *E-mail for correspondence: [email protected] https://doi.org/10.18034/abr.v8i3.164 ABSTRACT The purpose of the study is to classify the different factors influencing the success of a Bengali film, and in this regard, a total sample of 296 respondents has been interviewed through a structured questionnaire. To test the study, Pearson’s product moment correlation, ANOVA and KMO statistic has been used and factor analysis is used to group the factors needed to develop for producing a successful film. The study reveals that the first factor (named convenient factor) is the most important factor for producing a film as well as to grab the attention of the audiences by 92% and competitive advantage by 71%, uniqueness by 81%, supports by 64%, features by 53%, quality of the film by 77% are next consideration consecutively according to the general people perception. The implication of the study is that the film makers and promoters should consider the factors properly for watching more films of the Dhallywood industry in relation to the foreign films especially Hindi, Tamil and English. The government can also take the initiative for the betterment of the industry through proper governance and subsidize if possible. -

Representing Identity in Cinema: the Case of Selected

REPRESENTING IDENTITY IN CINEMA: THE CASE OF SELECTED INDEPENDENT FILMS OF BANGLADESH By MD. FAHMIDUL HOQUE Thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirement For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy June 2010 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I must acknowledge first and offer my gratitude to my supervisor, Dr. Shanthi Balraj, Associate Professor, School of Arts, Universiti Sains Malaysia (USM), whose sincere and sensible supervision has elevated the study to a standard and ensured its completion in time. I must thank the Dean and Deputy Dean of School of Arts, USM who have taken necessary official steps to examining the thesis. I should thank the Dean of Institute of Post-graduate Studies (IPS) and officials of IPS who have provided necessary support towards the completion of my degree. I want to thank film directors of Bangladesh – Tareque Masud, Tanvir Mokammel, Morshedul Islam, Abu Sayeed – on whose films I have worked in this study and who gave me their valuable time for the in-depth interviews. I got special cooperation from the directors Tareque Masud and Catherine Masud who provided enormous information, interpretation and suggestions for this study through interview. Tanvir Mokammel was very kind to provide many materials directly related to the study. I must mention the suggestions and additional guidance by film scholar Zakir Hossain Raju who especially helped me a lot. His personal interest to my project was valuable to me. It is inevitably true that if I could not get the support from my wife Rifat Fatima, this thesis might not be completed. She was so kind to interrupt her career in Dhaka, came along with me to Malaysia and gave continuous support to complete the research. -

Representation of Liberation War in the Films of 90S

[Scientific Articles] Shifat S., Ahmed S. Representation of Liberation War in the Films of 90s REPRESENTATION OF LIBERATION WAR IN THE FILMS OF 90s Shifat S. Assistant Professor at Jahangirnagar University Journalism & Media Studies Department (Dhaka, Bangladesh) [email protected] Ahmed S. Assistant Professor at Jahangirnagor University Journalism & Media Studies Department (Dhaka, Bangladesh) [email protected] Abstract: In the history of Bangladesh, the liberation War of 1971 is an unforgettable period. Through the bloody struggle of nine months their independence is achieved, which simultaneously contains the spirit of Bengali spirit, love and patriotism towards the motherland. Bangladeshi people participated in the spirit of love and extreme sacrifice from every sphere of society for the motherland and Bengali language. In addition to other mass media, film is an equally important medium and in films there is a great deal of effort to uncover the vital role of creating ideas and consciousness among people about the liberation War. With this in mind, this study tried to find out, how the films conceptualise the spirit and history of the liberation War in the 90s after two decades of freedom. This study has been conducted taking three feature films of the 90s based on the liberation war. Adopting the content analysis method, the study aimed to answer two questions- ‘How do the films of the 90s represent the liberation War of Bangladesh?’; and, ‘To portray the history of the liberation war, what kind of content and contexts have been used in these films?’ The results showed that the films of the nineties signify the jana-itihas of Bangladesh by attaining the concept of the liberation War in a distinctive way. -

Faculty of Security & Strategic Studies

List of Eligible Candidates for Written Test Faculty/Program: Faculty of Security & Strategic Studies Session: Jan - Jun 2019 Count: 7128 SL# Name Father Name Quota Test Roll Military, Senate and 1 ,MD. SHAZZADUL KABIR MD. ANAMUL KABIR 1218192243 Syndicate Members 2 A B M MUSFIQUR RAHMAN MD MURAD HOSSAIN Not Applicable 1218194793 A K M RAZUNAL HOQUE Military, Senate and 3 MD SHAHIDUL ISLAM 1218196986 SHAGOR Syndicate Members Military, Senate and 4 A K M SAZZADUL ISLAM MD. SHAHIDUL ISLAM 1218195475 Syndicate Members 5 A K M TAIMUR SAKIB A K M AZIZUR RAHMAN Not Applicable 1218190443 Military, Senate and 6 A S M NAIMUR RAHMAN MD MOSHIUR RAHMAN 1218193266 Syndicate Members 7 A. B. M. NAHIN ALAM A. K. M. ZAHANGIR ALAM Not Applicable 1218194579 8 A. B. M. TAHMID AHABAB A. S. M. ATIQUR RAHMAN Freedom Fighter 1218190514 9 A. K. M LUTHFUL HAQUE A. K. M MONJURUL HAQUE Not Applicable 1218196529 10 A. K. M SAFAYAT NABIL A. K. M AKTARUZZAMAN Not Applicable 1218192772 A. K. M. MUNTASIR 11 A. K. M. AZAD Not Applicable 1218192608 MAHMUD 12 A. K. M. NAHID KHAN ALI AHMED KHAN Not Applicable 1218196224 13 A. K. M. NAHYAN ISLAM A. K. M. NURUL ISLAM Not Applicable 1218195082 Military, Senate and 14 A. N. M. ROBIN MD. FARUQUE HOSSAIN 1218193432 Syndicate Members 15 A. N. M. SAKIB MD. RUHUL AMIN Not Applicable 1218195033 16 A. S. M SHAFAYAT JAMIL A.B.M. HASAN SHAHID JAMIL Not Applicable 1218190372 A. S. M. AKIBUZZAMAN A. U. M. ATIKUZZAMAN 17 Not Applicable 1218193673 SARKER SHARKER Military, Senate and 18 A. -

Agun Niye Khela

Agun Niye Khela Agun Niye Khela (1st) is a most popular (Famous) book of Masud Rana Series. Just click & download. If you want to read online, please go to (✅Click For Read Online) button and wait few seconds... Portable Document Format (PDF) file size of Agun Niye Khela 1 is 11.26 MB. If you want to read online Agun Niye Khela 1, please go to (Click For Read Online) button and wait few seconds. Else late us a moment to verify the Agun Niye Khela 1 download using the captcha code. PDF Document Agun Niye Khela [Part 1] .pdf - Download PDF file agun-niye-khela-part-1.pdf (PDF 1.7, 7.4 MB, 314 pages). Document preview. Download original PDF file. Agun Niye Khela [Part 1].pdf (PDF, 7.4 MB). Related documents. Link to this page. Agun Niye Khela is a 1967 Bangladeshi film directed by Zahir Raihan and stars Razzak and Sujata. Music. It is the debut film of veteran singer Sabina Yasmin. Director Zahir Raihan and composer Altaf Mahmud gave her a chance to sing the song "Modhu Jochnar Dipaboli". Several days went by, the singer feared that her song may be cut of the film. But the music director then gave her another song "Ekti Pakhi Dupure Rode Shongihara Eka" with then established singer Mahmudun Nabi.[1]. Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License; additional terms may apply. By using this site, you agree to the Terms of Use and Privacy Policy. Wikipedia® is a registered trademark of the Wikimedia Foundation, Inc., a non-profit organization. -

Unit 10 Dreams

English One Unit 10 Dreams Objectives After you have studied this unit you should will be able to • participate in conversations and discussions. • understand and narrate problems. • take and give interviews. • Write paragraphs and dialogues Overview Lesson 1: I have a dream Lesson 2: What I dream to be Lesson 3: They had dreams 1 Lesson 4: They had dreams 2 Answer Key Unit-10 Page # 123 SSC Programme Lesson 1: I have a dream Hi, I am Maitri Mutsuddi. My father Hello! I am Mofakkhar Hasan. I live is a freedom fighter and my mother is in a slum with my parents and sisters. a teacher. They both dream for a I know how cruel poverty can be! I golden Bangladesh and inspire me to feel very sorry to the poor people do something significant, something suffering in my slum. After I have positive for the country. Often I think finished my education, I will be a what to do to fulfil their expectations social worker to fight against the in future. Finally I have decided to be social injustice and poverty. ‘Change a politician and work for my is the word I believe in to make motherland. How is it? Bangladesh a golden Bengal.’ I am Amitabh Kar, when I say to my My name is Ruth Antara Chowdhury. friends that I would like to be a space I believe that society cannot be traveler, they laugh. But I really want enlightened without to be that. If people from other education.Education lights the candle countries can win the moon, and roam in people’s heart. -

Board of Intermediate and Secondary Education, Jessore. Junior School Certificate Examination, 2018 Stipend List Page No : 1

Board of Intermediate and Secondary Education, Jessore. Junior School Certificate Examination, 2018 Stipend List Page No : 1 Serial Centre Roll No. Name Name of Passing Institution Category :TalentTalent Thana Thana : Khulna: Khulna Sadar Sadar Zilla : Khulna Zilla : Khulna Total : 30 0001 Khulna - 393 357410 F. M. Rafi Khulna Zilla School 0002 Khulna - 393 357409 Md. Junaeid Hossain Khulna Zilla School 0003 Khulna - 393 357411 Md Nakibuzzaman Likhon Khulna Zilla School 0004 Khulna - 393 357361 Amartya Halder Khulna Zilla School 0005 Khulna - 393 357356 Shuvro Debnath Khulna Zilla School 0006 Khulna - 393 357500 Md. Ariful Haque Khulna Zilla School 0007 Khulna - 393 357444 Abdullah Al Mamun Khulna Zilla School 0008 Fatema - 495 430472 Aurnab Ray St. Joseph's High School 0009 Khulna - 393 357360 Md Alvi Amin Khulna Zilla School 0010 Khulna - 393 357366 Abu Darda Tun Khulna Zilla School 0011 Fatema - 495 430469 Pias Nasker St. Joseph's High School 0012 Iqbal Nagar - 448 398109 Gazi Sazid Raiyan S O S Hermann Gmeiner School 0013 Khulna - 393 357374 Alif Ibn Azad Khulna Zilla School 0014 Khulna - 393 357363 Adrito Roy Khulna Zilla School 0015 Khulna - 393 357355 Arghyo Jyoti Mahali Khulna Zilla School 0016 Khulna - 201 200483 Mayesha Sadia Islam Govt. Coronation Secondary Girls' School 0017 Khulna - 201 200463 Nusaaiba Binte Masum Govt. Coronation Secondary Girls' School 0018 Khulna - 201 200549 Shithi Hazra Govt. Coronation Secondary Girls' School 0019 Khulna - 393 357758 Kongkona Saha Dola Fatema High School 0020 Khulna - 201 200484 Moyouri Zaman Mou Govt. Coronation Secondary Girls' School 0021 Khulna - 201 200398 Oishe Chakrobortty Govt. Coronation Secondary Girls' School 0022 Khulna - 201 200550 Anwesha Sarker Nisha Govt. -

Suggestions for SSC 2020

BANGLADESH INTERNATIONAL SCHOOL & COLLEGE DOHS, Mohakhali, Dhaka Cantt Suggestions for SSC 2020 Subject : Bangla 1st Paper we:`ªóe¨: Ávb ¯Í‡ii Rb¨ wbw`©ó †Kvb mv‡Rkb cÖ‡hvR¨ bq | g~jcvV, †jLK cwiwPwZ (Rb¥-g„Zy¨ mvj, D‡jøL‡hvM¨ eB, cÖvß c`K ) kãv_© I UxKv fv‡jvfv‡e co‡Z n‡e | Avg AvuwUi †fucy K. Ávbg~jK 1. nwin‡ii evwo †_‡K f~eb gyLvwR©i evwo KZ wgwb‡Ui c_? 2. Acyi wU‡bi †fucy-evuwkwU Kq cqmvi wQj? 3. Acy gvby‡li Mjvi AvIqvR †c‡q Kx jywK‡q iv‡L? 4. nwin‡ii cyÎ †ivqv‡K e‡m Kx KiwQj? 5. Acyi w`w`i bvg wK? 6. wef~wZf~lb e‡›`vcva¨vq Rb¥ KZ mv‡j? 7. nwini iv‡qi ÁvwZ åvZvi bvg Kx? 8. Kv‡Vi †MvowU wK‡mi gZ c‡o wQj? 9. KqUvi mgq Acy †Ljv KiwQj? 10. ÔAvg AvuwUi †fucyÕ MíwUi iPwqZv †K? 11. ÔAvg AvuwUi †fucyÕ M‡í Kx ai‡bi Rxe‡bi eb©bv i‡q‡Q? 12. `yMv‡`i evwoi Pvicv‡k Kx wQj? 13. Acyi †PvL wKiƒc wQj? 14. `yM©v Zvi Aewkó Av‡gi PvKjv¸‡jv Kx K‡iwQj? 15. mZ¨ cÖKvk Ki‡Z mvnm bv ‡c‡q Acy w`w`i w`‡K Kxiæc `„wó‡Z †P‡qwQj? 16. wef~wZf~lb e‡›`vcva¨vq †Kvb Dcb¨v‡mi Rb¨ iex›`ª cyi®‹v‡i f~wlZ nb? 17. Acy‡K †Zj Avi byb Avb‡Z e‡jwQj †K? 18. nwin‡ii †Q‡ji bvg Kx? 19. `~M©vi m‡½ Acy m¤úK© Kx? 20. -

A Brief History of Music in Bangladeshi Cinema Before Liberation (1956-1970)

Vol-6 Issue-3 2020 IJARIIE-ISSN(O)-2395-4396 A Brief History of Music in Bangladeshi Cinema before liberation (1956-1970). Ruksana Karim Lecturer, Dept. of Music, Jagannath University, Dhaka, Bangladesh. Former research fellow, 2015-16 & 2018-19 Bangladesh Film Archive. Abstract This study describes the beginning of musical journey of Bangladeshi cinema. The 49 years old country ‘Bangladesh’ has a beautiful history of cinema and music (near about 122 years old). But the journey was not as easy as present when Bangladesh (previous East Pakistan) was a part of Pakistan. This paper is a complete narration of musical perspective in Bangladeshi cinema and introduces authentic Bangladeshi culture. The history of Bangladeshi cinema is very much related with Indo-Pak sub continental cinema history. From another aspect, this study discusses the positive sides, all ups and downs of the beginning period of Bangladeshi cinema music. The methodology of this study is purely based on historical analysis and description that includes quite observation, literature reviews and interviews. Music in Bangladeshi cinema is strongly connected to the roots of its culture and this chapter really needs a quality research to go forward. From another view, this study introduces a good number of film makers and music directors of Bangladesh who had a lot of art work to make the history, classifies the film song in different categories and describes how the socio-economic condition presents through music in cinemas? It seems like a mirror, which is only the reflection, their life, culture and Bengali nationality. To forward this glory to the future generation and other nations, there is no alternative of describing the fundamental history as this study is doing. -

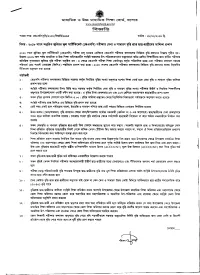

Fdmq{Qrffrfu

{f$fr-ssffiFFfl 6il6,E1*I )e-)8, g'tF[Fr (Tlv, <-qfr{sTl<, Et$',t-)Q.)) 6pl-q 3 bgc'e8lE, bvgbb)o, TIlq B b\9gbu)5 \o\oq|fdmq{qrffrfu @ ffi {r$fr-s s Emql,flrfrrF[qt 6<t6, u'l-+t r " li so[B " qq< ' >/q[&&/looc/qoqo vlkll : tc-ob-Q.or.o Rrr : \o{o ql-c6m{Hrft-rx;qqtEtFrrb(,rnnxfr;'rftfirT-{lTfl{frfuro^ 6{t66{ "fr{18'\e "qtqt<"l{ff etrilq {q-m r aq : {l$frs. s Em;FfFrqRqi66ffi'{KsR-eq.o\.oooo.))1.e).oo9.){-8s.e \'tfrt, )o/ou/qoqotq, BqTs frffi € T(q{ cqfuru rt$fr-s rg Emqlr{fur FitT .$6, ErsI- qr \o\o fi6{n rt'<ifuo Te qrffiFr$B 1enerfr) €l.t-R Fqt+m{ Gfucs Fq<ffis .k\t frEI{, nT-{frs s rrfit*" fte1 ft-strt piqpTm-< stB$Ipw " ffifilfu" € "qF@" qffi's-<T ECEr I T{otfr firr ftfum qmlft e 'g 1ft< slfr-fi el"ts"q s-fi ccr6s I ,r 1fuqq6sqrrFw<fufrs{ e ftfrfiETq-{"Bt 6qr+D-E(qqr< I .lvffi ) I (O1fu{curcq(t@<fonmmcqFNtEB$T{cqrroqftq'f*q(.$qtsr.<E0.{qrr6q c{ qetf{-{ qm Erg'.r q<]'ccs6s q<( q{rs <f qqq Fisr$( efqr-{'rq qqr{ ql'c'lffi g6Ts Et"St{ cql-r frR qd mwc<-o @< Brctqq' s-{cu sr< r q'Nr{'q-{s qhl+ ("I) {$E nmftm< cqtr<.1, frrrFrc{ FKfis EIRB \e {tcffi crcatcs 1fu s<T qr< I qqrrm q-dT qGtTr{ ('f) csT{ Fts{ft Ew 6qfue w$flfrs Frs.I sffqt ccE 1ftr "fl\sfl-< dtrr {cq ffiqr<{ r ('i) ,! Ifuerqt{ q(fi, qK \3 ffi{]q qr"ns frfiRs r {c-{M-{Grk{ {rsk c$]-+ sFEt ql mFnxt st "fffi<T<l&q+TF 'tBl-6{ I .r{ a. -

A Nayyar Mp3 Film Songs Free Download Urdu A.Nayyar Makes His Final Exit

a nayyar mp3 film songs free download urdu A.Nayyar makes his final exit. Not many people have inspired me as much as legendary singer Arthur Nayyar, popularly known as A. Nayyar - who passed away in Lahore this past Friday. ObituaRy. A look back at the illustrious career of the acclaimed singer who passed away in Lahore recently. Not many people have inspired me as much as legendary singer Arthur Nayyar, popularly known as A. Nayyar - who passed away in Lahore this past Friday. For a person growing up in the ’80s and ’90s, Nayyar was a formidable name since he was always appearing on TV while his songs were aired on TV shows and films featuring him as a playback singer were screened thrice a week. Even holidays were special as movies like Deewane Do, Faisla and special programs like Jhankaar and Eid shows showcased his hit numbers. Months before his death, I got a chance to speak to the inspiring artist but sadly it was about the death of Robin Ghosh, another legendary music director who had passed away. For most part of our conversation, Nayyar sahib was crying as he noted, “Robin bhai mera bhai hi nahi, mera baap tha” (Robin was not just my brother; he was my father). Eventually, he found his stride as he spoke to me about the songs he sang for Ghosh. The best part was his hospitable open invitation to visit him in Lahore whenever I was there next; a trip that never materialized. What made Arthur Nayyar – a Christian from Ransonabad village of Sahiwal district – special was his ability to adapt and learn. -

Hoek S 2016 Mirrorofmovement

Edinburgh Research Explorer Mirrors of Movement Citation for published version: Hoek, L 2016, 'Mirrors of Movement: Aina, Afzal Chowdhury’s cinematography and the interlinked histories of the cinema in Pakistan and Bangladesh', Screen, vol. 57, no. 4, pp. 488-495. https://doi.org/10.1093/screen/hjw052 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1093/screen/hjw052 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: Screen Publisher Rights Statement: This is a pre-copyedited, author-produced version of an article accepted for publication in Screen following peer review. The version of record for 'Mirrors of movement: Aina, Afzal Chowdhury’s cinematography and the interlinked histories of cinema in Pakistan and Bangladesh' Lotte Hoek Screen (2016) 57 (4): 488-495 is available online at:https://doi.org/10.1093/screen/hjw052 General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 03. Oct. 2021 Mirrors of movement: Aina, Afzal Chowdhury’s cinematography and the interlinked histories of cinema in Pakistan and Bangladesh LOTTE HOEK In 1977 a film was released in Pakistan that broke all box-office records.