8.5 X12.5 Doublelines.P65

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How Useful Are Episcopal Ordination Lists As a Source for Medieval English Monastic History?

Jnl of Ecclesiastical History, Vol. , No. , July . © Cambridge University Press doi:./S How Useful are Episcopal Ordination Lists as a Source for Medieval English Monastic History? by DAVID E. THORNTON Bilkent University, Ankara E-mail: [email protected] This article evaluates ordination lists preserved in bishops’ registers from late medieval England as evidence for the monastic orders, with special reference to religious houses in the diocese of Worcester, from to . By comparing almost , ordination records collected from registers from Worcester and neighbouring dioceses with ‘conven- tual’ lists, it is concluded that over per cent of monks and canons are not named in the extant ordination lists. Over half of these omissions are arguably due to structural gaps in the surviving ordination lists, but other, non-structural factors may also have contributed. ith the dispersal and destruction of the archives of religious houses following their dissolution in the late s, many docu- W ments that would otherwise facilitate the prosopographical study of the monastic orders in late medieval England and Wales have been irre- trievably lost. Surviving sources such as the profession and obituary lists from Christ Church Canterbury and the records of admissions in the BL = British Library, London; Bodl. Lib. = Bodleian Library, Oxford; BRUO = A. B. Emden, A biographical register of the University of Oxford to A.D. , Oxford –; CAP = Collectanea Anglo-Premonstratensia, London ; DKR = Annual report of the Deputy Keeper of the Public Records, London –; FOR = Faculty Office Register, –, ed. D. S. Chambers, Oxford ; GCL = Gloucester Cathedral Library; LP = J. S. Brewer and others, Letters and papers, foreign and domestic, of the reign of Henry VIII, London –; LPL = Lambeth Palace Library, London; MA = W. -

Winchcombe to Burford 54Km Contour Information B4058 South Cerney Kempsford B4014 TADDINGTON/SNOWSHILL

Great Comberton A4184 Elmley Castle B4035 Netherton B4632 B4081 Hinton on the Green Kersoe A38 CHIPPING CAMPDEN Key to Map A46(T) Aston Somerville Uckinghall Broadway Day Ashton under Hill Symbols: Kemerton At a Glance A438 (T) 5 M50 B4081 Wormington B4479 Laverton B4080 Beckford Blockley WinchcombeB4078 to Burford Ashchurch The first few miles of this A Road for Tewkesbury Bushley B4079 Great Washbourne Stanton A38 A38 A417 TEWKESBURY stretch take you into the hills B Road A438 Alderton Snowshill 11 TR SP THE SLAUGHTERS. Care crossing B4068. A438 Bourton-on-the-Hill B4079 A44 with the route levelling out Minor Road M5 Teddington B4632 2 12 TL SP UPPER SLAUGHTER/LOWER SWELL. Stanway towards Burford. You are going Motorway B4208 Dymock M50 A424 Linkend Oxenton Didbrook A435 2 PH 6 13 TR SP LOWER SLAUGHTER/BOURTON ON THE Dixton Gretton 3 to visit some of the best known Cutsdean Built-up Area Hailes 5 Deerhurst WATER. Kempley 1 PH Corse Ford villages of the Cotswolds on B4213 B4211 B4213 PH Gotherington 7 Tredington WINCHCOMBE Farmcote 14 TR SP LOWER SLAUGHTER/BOURTON ON THE Roundabouts Botloe’s Green Tirley PH B4077 Apperley 4 Condicote this stretch and in high summer Bishop’s Cleeve PH Several 1 4 WATER. Temple Guiting Hardwicke Railway Stations Lower Apperley some of them can be very busy, Upleadon Haseld Coombe Hill 15 TR SP UPPER SLAUGHTER. Kineton B4221 River Severn Orchard Nook PH A417 Gorsley A417 particularly Bourton on the Water. Railway Lines Newent A436 16 TL at Stone Bridge/Small Grassed Roundabout. Kilcot A4091 Southam Barton Hartpury Ashleworth Boddington Lower Swell Most of the route is along quiet B4224 PH Guiting Power PH 17 At T junction TL SP BOURTON ON THE WATER/THE Lakes 11 Charlton Abbots PH 8 B4216 Prestbury 12 13 country lanes. -

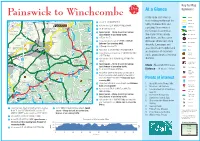

Painswick to Winchcombe Cycle Route

Great Comberton A4184 Elmley Castle B4035 Netherton B4632 B4081 Hinton on the Green Kersoe A38 CHIPPING CAMPDEN A46(T) Aston Somerville Uckinghall Broadway Ashton under Hill Kemerton A438 (T) M50 B4081 Wormington B4479 Laverton B4080 Beckford Blockley Ashchurch B4078 for Tewkesbury Bushley B4079 Great Washbourne Stanton A38 A38 Key to Map A417 TEWKESBURY A438 Alderton Snowshill Day A438 Bourton-on-the-Hill Symbols: B4079 A44 At a Glance M5 Teddington B4632 4 Stanway M50 B4208 Dymock Painswick to WinchcombeA424 Linkend Oxenton Didbrook A435 PH A hilly route from start to A Road Dixton Gretton Cutsdean Hailes B Road Kempley Deerhurst PH finish taking you through the Corse Ford 6 At fork TL SP BRIMPSFIELD. B4213 B4211 B4213 PH Gotherington Minor Road Tredington WINCHCOMBE Farmcote rolling Cotswold hills and Tirley PH 7 At T junctionB4077 TL SP BIRDLIP/CHELTENHAM. Botloe’s Green Apperley 6 7 8 9 10 Condicote Motorway Bishop’s Cleeve PH Several capturing the essence of Temple8 GuitingTR SP CIRENCESTER. Hardwicke 22 Lower Apperley Built-up Area Upleadon Haseld Coombe Hill the Cotswold countryside. Kineton9 Speed aware – Steep descent on narrow B4221 River Severn Orchard Nook PH Roundabouts A417 Gorsley A417 21 lane. Beware of oncoming traffic. The route follows mainly Newent A436 Kilcot A4091 Southam Barton Hartpury Ashleworth Boddington 10 At T junction TL. Lower Swell quiet lanes, and has some Railway Stations B4224 PH Guiting Power PH Charlton Abbots PH11 Cross over A 435 road SP UPPER COBERLEY. strenuous climbs and steep B4216 Prestbury Railway Lines Highleadon Extreme Care crossing A435. Aston Crews Staverton Hawling PH Upper Slaughter descents. -

1570 1 1570 at WINDSOR CASTLE, Berks. Jan 1,Sun

1570 1570 At WINDSOR CASTLE, Berks. Jan 1,Sun New Year gifts. January 3-29: William Drury, Marshal of Berwick, and Sir Henry Gates, were special Ambassadors to Scotland, sent to request Regent Moray to surrender the captured Earl of Northumberland, a leader of the Rising. After long negotiations, and payment of a large sum of money, the Earl was brought to England in 1572 and was executed at York. Anne (Somerset), Countess of Northumberland, lived abroad in Catholic countries from August 1570 to her death in 1591. Jan 6,Fri play, by the Children of the Chapel Royal.T Jan 7,Sat new appointments, of Treasurer of the Household, Controller of the Household, and Serjeant-Porter of Whitehall Palace. Jan 8, Windsor, Sir Henry Radcliffe to the Earl of Sussex, his brother: ‘Yesterday Mr Vice-Chamberlain [Sir Francis Knollys] was made Treasurer; and Sir James Croft Controller, and Sir Robert Stafford Serjeant-Porter’. ‘It is thought Sir Nicholas Throgmorton shall be Vice-Chamberlain, and Mr Thomas Heneage Treasurer of the Chamber’. [Wright, i.355]. Croft became a Privy Councillor by virtue of his office; Heneage became Treasurer of the Chamber on Feb 15; a Vice-Chamberlain was appointed in 1577. Jan 8,Sun sermon, Windsor: Thomas Drant, Vicar of St Giles, Cripplegate. Text: Genesis 2.25: ‘They were both naked, Adam and Eve, and blushed not’. Drant: ‘To be naked...is to be without armour, it is to be without apparel’... ‘Dust is Adam...Dust are all men...Rich men are rich dust, wise men wise dust, worshipful men worshipful dust, honourable men honourable dust, majesties dust, excellent majesties excellent dust’.. -

7-Night Cotswolds Guided Walking Holiday

7-Night Cotswolds Guided Walking Holiday Tour Style: Guided Walking Destinations: Cotswolds & England Trip code: BNBOB-7 1 & 2 HOLIDAY OVERVIEW Gentle hills, picture-postcard villages and tempting tea shops make this quintessentially English countryside perfect for walking. On our Guided Walking holidays you'll discover glorious golden stone villages with thatched cottages, mansion houses, pastoral countryside and quiet country lanes. WHAT'S INCLUDED • High quality en-suite accommodation in our country house • Full board from dinner upon arrival to breakfast on departure day • 5 days guided walking and 1 free day • Use of our comprehensive Discovery Point • Choice of up to three guided walks each walking day • The services of HF Holidays Walking Leaders www.hfholidays.co.uk PAGE 1 [email protected] Tel: +44(0) 20 3974 8865 HOLIDAYS HIGHLIGHTS • Explore the beautiful countryside and rich history of the Cotswolds • Gentle hills, picture-postcard villages and tempting tea shops make this quintessentially English countryside perfect for walking • Let your leader bring the picturesque countryside and history of the Cotswolds to life • In the evenings relax and enjoy the period features and historic interest of Harrington House ITINERARY Version 1 Day 1: Arrival Day You're welcome to check in from 4pm onwards. Enjoy a complimentary Afternoon Tea on arrival. Day 2: South Along The Windrush Valley Option 1 - The Quarry Lakes And Salmonsbury Camp Distance: 6½ miles (10.5km) Ascent: 400 feet (120m) In Summary: A circular walk starts out along the Monarch’s Way reaching the village of Clapton-on-the-Hill. We return along the Windrush valley back to Bourton. -

Players and Performances in Early Modern Gloucester, Tewkesbury and Bristol

Players and Performances in Early Modern Gloucester, Tewkesbury and Bristol SARAH ELIZABETH LOWE A thesis submitted to The University of Gloucestershire in accordance with the requirements to the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Education, Humanities and Sciences February 2008 i ABSTRACT This thesis is an analysis of the responses in the early modern period of civic and church authorities to local and visiting groups of players in Gloucester, Tewkesbury and Bristol. It is also an examination of the venues in which these groups performed. Reactions to these groups varied, and this study explores how these, both positive and negative, were affected by economic, legal and cultural factors. The thesis proceeds chronologically, and is thus divided into twenty-year intervals in order to draw the most effective comparisons between the three urban centres over a number of decades. The first period under examination, the 1560s, records the early reaction of the three settlements to the phenomenon of the Elizabethan travelling company. The relationship between the regional authorities and the patrons comes to the fore in the second period, the 1580s, as the dominance of the ambitious Earl of Leicester grew in the region. Legislation decreeing the withdrawal of mayoral control over itinerant troupes at the close of the sixteenth century, the third period, released civic officials from previous obligations and this influenced the level and character of their hospitality towards the ‘noble’ companies. Although evidence is scarce, the records of Gloucester, Tewkesbury and Bristol contain clues to an attitude towards these entertainers during the reign of James I, the final period under scrutiny. -

Bess of Hardwick) Gave the Queen an Embroidered Gown Made by William Jones, the Queen’S Tailor (Cost Over £100)

1592 1592 At WHITEHALL PALACE Jan 1,Sat New Year gifts. Gift roll not extant, but Elizabeth Countess of Shrewsbury (Bess of Hardwick) gave the Queen an embroidered gown made by William Jones, the Queen’s tailor (cost over £100). Her other gifts included: Ramsey, the Court Jester, 20s; six of the Queen’s trumpeters, 5s each.SH Jan 1: Queen to Lord Burghley, Lord Howard of Effingham, and Lord Hunsdon: Commission to execute the office of Earl Marshal.RT This post, in overall charge of the College of Arms, was vacant since Earl of Shrewsbury died, 1590. Also Jan 1: play, by Lord Strange’s Men.T Jan 2,Sun French Ambassadors at Whitehall for audience.HD Beauvoir, resident Ambassador, with Duplessis-Mornay, who took his leave. Lord Burghley kept a diary in 1592, shown here as HD. [HT.xiii.464-6]. Also Jan 2: play, by Earl of Sussex’s Men.T Jan 6,Thur play, by Earl of Hertford’s Men.T Jan 6: Allegations against Sir John Perrot, former Lord Deputy of Ireland, noted by the law officers, included: Perrot boasted that he was King Henry’s son; he said the Irish had a prophecy that a bird would do them good, and applied it to himself, he having a parrot in his crest; he uttered ‘immodest and venomous words’ about the Queen; of the Council in Ireland he said he cared no more for them than for so many dogs. [SP12/241/7]. Robert Naunton: ‘Sir Thomas Perrot his father was a Gentleman to the Privy Chamber to Henry the Eighth and in the court married to a lady of great honour and of the King’s familiarity...If we go a little further and compare his picture, his qualities, his gesture and voice with that of the King’s.. -

English Monks Suppression of the Monasteries

ENGLISH MONKS and the SUPPRESSION OF THE MONASTERIES ENGLISH MONKS and the SUPPRESSION OF THE MONASTERIES by GEOFFREY BAS KER VILLE M.A. (I) JONA THAN CAPE THIRTY BEDFORD SQUARE LONDON FIRST PUBLISHED I937 JONATHAN CAPE LTD. JO BEDFORD SQUARE, LONDON AND 91 WELLINGTON STREET WEST, TORONTO PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN IN THE CITY OF OXFORD AT THE ALDEN PRESS PAPER MADE BY JOHN DICKINSON & CO. LTD. BOUND BY A. W. BAIN & CO. LTD. CONTENTS PREFACE 7 INTRODUCTION 9 I MONASTIC DUTIES AND ACTIVITIES I 9 II LAY INTERFERENCE IN MONASTIC AFFAIRS 45 III ECCLESIASTICAL INTERFERENCE IN MONASTIC AFFAIRS 72 IV PRECEDENTS FOR SUPPRESSION I 308- I 534 96 V THE ROYAL VISITATION OF THE MONASTERIES 1535 120 VI SUPPRESSION OF THE SMALLER MONASTERIES AND THE PILGRIMAGE OF GRACE 1536-1537 144 VII FROM THE PILGRIMAGE OF GRACE TO THE FINAL SUPPRESSION 153 7- I 540 169 VIII NUNS 205 IX THE FRIARS 2 2 7 X THE FATE OF THE DISPOSSESSED RELIGIOUS 246 EPILOGUE 273 APPENDIX 293 INDEX 301 5 PREFACE THE four hundredth anniversary of the suppression of the English monasteries would seem a fit occasion on which to attempt a summary of the latest views on a thorny subject. This book cannot be expected to please everybody, and it makes no attempt to conciliate those who prefer sentiment to truth, or who allow their reading of historical events to be distorted by present-day controversies, whether ecclesiastical or political. In that respect it tries to live up to the dictum of Samuel Butler that 'he excels most who hits the golden mean most exactly in the middle'. -

Guiting Power Committee Report.Pdf

APPLICATION FOR A DEFINITIVE MAP MODIFICATION ORDER FOR ADDITIONAL LENGTH OF PUBLIC FOOTPATH AT CASTLETT BANK, PARISH OF GUITING POWER REPORT OF THE COMMISSIONING DIRECTOR FOR COMMUNITIES & INFRASTRUCTURE 1. PURPOSE OF REPORT To consider the following application: Nature of Application: Additional public footpath Parish: Guiting Power Name of Applicant: Raymond Sheasby, Guiting Power Parish Footpaths Warden Date of Application: 28 September 2009 2. RECOMMENDATION That no order be made to add a public footpath, due to insufficient evidence 3. RESOURCE IMPLICATIONS Cost of advertising Order in the local press, which has to be done twice, is approximately £500 per notice. In addition, the County Council is responsible for meeting the costs of any Public Inquiry associated with the application. If the application were successful, the path would become maintainable at the public expense. 4. SUSTAINABILITY & EQUALITY IMPLICATIONS No sustainability or equality implications have been identified. 5. STATUTORY AUTHORITY Section 53 of the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981 imposes a duty on the County Council, as surveying authority, to keep the Definitive Map and Statement under continuous review and to modify it in consequence of the occurrence of an ‘event’ specified in sub section [3]. Any person may make an application to the authority for a Definitive Map Modification Order on the occurrence of an ‘event’ under section 53 [3] [b] or [c]. The County Council is obliged to determine any such application that satisfies the required submission criteria in accordance with schedule 14 of the Act. 6. DEPARTMENTAL CONTACT 1 Andrew Houldey, Asset Data Officer (PROW Definitive Map), Definitive Map Unit, Highway Records, Asset Data Team. -

Craft Beer in the Spotlight AONB & Green Belt in Peril Events & Activities for Spring

ISSUE 223 • SPRING 2017 www.chilternsociety.org.uk • CHILTERN SOCIETY MAGAZINE Craft beer in the spotlight AONB & green belt in peril Events & activities for spring HERITAGE • CONSERVATION • ENVIRONMENT • WILDLIFE • LEISURE ISSUE 223 • SPRING 2017 www.chilternsociety.org.uk • CHILTERN SOCIETY MAGAZINE In this Craft beer in the spotlight AONB & green belt in peril Events & activities for spring HERITAGE • CONSERVATION • ENVIRONMENT • WILDLIFE • LEISURE Beech trees and bluebells on Crowell Common issue (Clive Ormonde) NEWS & VIEWS 3 EDITOR 22 4 CRAFT BEER IN THE SPOTLIGHT SOCIETY Society Awards 2017 EVENTS & 5 CHILTERNS FOOD & DRINK FESTIVAL ACTIVITIES 14 AWARD FOR BARNABY USBORNE – sPRING 2017 23 CHILTERNS WALKING FESTIVAL 26 MEET OUR NEW WALKS CO-ORDINATOR & TRUSTEES 28 WORKING TOGETHER FOR THE CHILTERNS Interview with CCB Chief Executive, Sue Holden 33 LACEY GREEN WINDMILL 09 Opening hours 2017 36 LETTERS RESTORING WHITELEAF 43 bERKHAMSTED WALK 2017 CROSS ENVIRONMENT 14 NEW BOX AT IBSTONE 18 AONB & GREEN BELT IN PERIL Paul Mason outlines the Society’s proposed countermeasures 27 FAIR GAME? SPECIAL Gill Kent with a farmer’s perspective MEMBER on culling OFFERS see page 40 37 WILDLIFE GREAT 6 HELP US BRING BACK THE FAMILY HAZEL DORMOUSE! DAYS OUT 32 WHO KILLED COCK ROBIN? AT COAM George Stebbing-Allen investigates 38 WHAT’S SPECIAL ABOUT THE CHILTERNS? Asks Tony Marshall PATRON: Rt Hon The Earl Howe HEAD OF CONSERVATION & DEVELOPMENT: Gavin Johnson PRESIDENT: Michael Rush HEAD OF MARKETING & MEMBERSHIP: Victoria Blane VICE PRESIDENTS: -

Official Visitors Guide 2009 Tourist Information

South Cotswolds & Vale of Severn Official Visitors Guide 2009 Tourist Information THORNBURY TIC The Town Hall, High Street, Thornbury (01454) 281638 [email protected] CHIPPING SODBURY TIC, The Clock Tower, High Street, Chipping Sodbury (01454) 888686 WOTTON-UNDER-EDGE Information Point Heritage Centre, The Chipping, Wotton-under-Edge (01454) 521541 Your guide TETBURY Tourist Information 33 Church Street, Tetbury GL8 8JG (01666) 503552 BRISTOL TIC Explore at Bristol, Anchor Road, Harbourside, Bristol BS1 5DB (0845) 408 0474 www.visitbristol.co.uk NAILSWORTH TIC 4 The Old George, Fountain Street, Nailsworth GL6 0BL 01453 839222 www.nailsworthtown.co.uk DURSLEY Information www.dursleytowncouncil.gov.uk email: [email protected] to the South Cotswolds & 4 Vale of Severn s a base for a weekend break or longer, the Severn Vale and South Cotswolds could hardly be Abetter placed. With easy access from both the M4 and M5, and with good rail links from Bristol, the area is ideally situated for a variety of day trips. The international city of Bristol with its exciting Harbour side development, and the graceful curves of Bath’s regency crescents offer chic shopping, theatres, and first class 6 restaurants and bars. The Mall at Cribbs Causeway and the new Cabot Circus in Bristol offer spectacular shopping experiences. The Wye Valley and Forest of Dean provide ideal territory for quiet rambles and picnics, as do the Severn Way and the Cotswold Way which mark the west and east boundaries of this area. Best of all, the area offers unsung treats right on the doorstep, such as unspoiled market towns, secretive Cotswold stone villages and delectable cream teas. -

Appendix 1: Case Study Selection - Desk-Based Assessment

Appendix 1: Case study selection - desk-based assessment Landscape character and pay Score (Limited Score (Excellent 5, Monastic house Monastic order Notes on history and estates Previous landscape study/ recording Availability of archive and research materials type 5, significant 1) poor 1) First Augustinian house founded in Wales, in 1108, of fluctuating wealth. Reasonable amount of primary sources - including a Cell established in Gloucester in 1136, became separate institutions then contemporary history (Brit Lib), though no cartulery reunited with the Gloucester site becoming the mother house in 1481. Core (except for Irish holdings). Good availability of other local manors, mills and spiritualities in Monmouthshire (Cwmyoy/ Honddu Procter's MSc dissertation and subsequent journal articles land grants and charters, manorial court rolls, Slade, Oldcastle, Redcastle and Stanton) and Herefordshire (Bishop's/ (2007a, 2007b, 2012) provide a preliminary overview of the Priory in upland Black Mountain possessions at Dissolution, estate and legal Llanthony Prima Canon's Frome, Burghill, Fawley, Foxley, Llanwarne, Newton, Walterstone, impact of the priory on its surrounding environs. Evans’ setting, outlying holdings across records, estate maps (Procter/ GA/ Monastic Wales/ Priory, Augustinian Widemarshmoor in Hereford, Yarsop), and extensive lands in Ireland. articles (1980, 1984) on the archaeological investigation of 3 4 Monmouthshire and Herefordshire NA). Good amount of secondary sources, including Monmouthshire Chapels, churches, tithes and other lands in Herefordshire (Brinsop, the Priory site in 1978 confirmed that the house’s economy, mainly in bocage landscape Rhodes listings of holdings (1989) Knight and Burybarn, Clodock, Cusop, Eardsley, Ffwyddog, Fossecombe, Howton, management of estates and landscape development had not McGraghan papers (GA) and a number of historical Kenderchurch, Langarnam, Llanveynoe, Longtown, Nethersfield, Olchon, been addressed.