“Spolia: Transcripts of the Stones of the Little Metropolis”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 BRITISH SCHOOL at ATHENS 47Th Annual Course For

1 BRITISH SCHOOL AT ATHENS 47th Annual Course for Undergraduates The Archaeology and Topography of Ancient Greece 18th August – 7th September 2019 PROVISIONAL ITINERARY DATE DAY TIME SITE AUGUST 08.30-23.30 Arrival at the BSA Sunday 18 1 20.00 Informal dinner Monday 19 2 08.00-09.30 Breakfast 09.30-10.15 Introductory Session in Finlay Common Room 10.15-11.00 Library and Archive Tour 11.00-11.30 Coffee Break in Finlay 11.30-13.00 Key Themes I: The history of archaeology and the archaeology of history in Greece (Museum) 13.00-14.00 Buffet Lunch in Dining Room 14.00-15.30 Key Themes II: Ways of approaching archaeological sites (Museum) 15.30-17.00 Key Themes III: Archaeological Science (Fitch) 19.30 BBQ on the Finlay Terrace Tuesday 20 3 07.30-08.30 Breakfast 08.30 The Acropolis (including the interior of the Parthenon) (Lunch – self bought) The south Slope of the Acropolis Wednesday 21 4 07.30-08.30 Breakfast 08.30 The Athenian Agora and Museum The Areopagos, Philopappos Hill, The Pnyx (Lunch – self bought) The Acropolis Museum Thursday 22 5 07.30-08.30 Breakfast 08.30 Kerameikos Library of Hadrian (Lunch – self bought) Roman Agora, Little Metropolis, Arch of Hadrian, Temple of Olympian Zeus Friday 23 6 07.30-08.30 Breakfast 08.30 The National Archaeological Museum I (Mycenaean gallery, Pottery collection) (Lunch – self bought) The National Archaeological Museum II (Sculpture collection) Saturday 24 7 08.00-09.00 Breakfast 09.00 Piraeus Museum FREE AFTERNOON Sunday 25 8 FREE DAY 2 Monday 26 9 07.30-08.30 Breakfast 08.30 BSA Museum Cycladic -

The Little Metropolis at Athens 15

Bucknell University Bucknell Digital Commons Honors Theses Student Theses 2011 The Littleetr M opolis: Religion, Politics, & Spolia Paul Brazinski Bucknell University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/honors_theses Part of the Classics Commons Recommended Citation Brazinski, Paul, "The Little eM tropolis: Religion, Politics, & Spolia" (2011). Honors Theses. 12. https://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/honors_theses/12 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses at Bucknell Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Bucknell Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Paul A. Brazinski iv Acknowledgements I would like to acknowledge and thank Professor Larson for her patience and thoughtful insight throughout the writing process. She was a tremendous help in editing as well, however, all errors are mine alone. This endeavor could not have been done without you. I would also like to thank Professor Sanders for showing me the fruitful possibilities in the field of Frankish archaeology. I wish to thank Professor Daly for lighting the initial spark for my classical and byzantine interests as well as serving as my archaeological role model. Lastly, I would also like to thank Professor Ulmer, Professor Jones, and all the other Professors who have influenced me and made my stay at Bucknell University one that I will never forget. This thesis is dedicated to my Mom, Dad, Brian, Mark, and yes, even Andrea. Paul A. Brazinski v Table of Contents Abstract viii Introduction 1 History 3 Byzantine Architecture 4 The Little Metropolis at Athens 15 Merbaka 24 Agioi Theodoroi 27 Hagiography: The Saints Theodores 29 Iconography & Cultural Perspectives 35 Conclusions 57 Work Cited 60 Appendix & Figures 65 Paul A. -

Day One Natalie Wei Today We Visited the Acropolis and Its Museum As Well As the Ancient Agora

Thursday, June 13th -- Day One Natalie Wei Today we visited the Acropolis and its museum as well as the ancient agora. It was hot enough to melt and the stones of the path up to the acropolis were well-worn, and slippery. When you arrive at the peak, the Parthenon is just… right there. I think everyone in my generation was introduced to Greek history and mythology through the Percy Jackson series, and that one large blue mythology book (with the gold meander on the edges and the stone in the center?) -- seeing the landmark in person was surreal, not only for its immense size and impossible-to-fathom age, but also because until yesterday, I had always seen Greece as a thing of legend and fiction. Standing foot here does not entirely register as reality. Much of the PArthenon is covered in scaffolding, which lent to the feeling of artificiality, almost as if a movie set were being constructed. It is much more interesting to see a structure rather than piles of rubble, but I get a sense of unease about restorations. It will never be the same--how could we know? Besides, for materials, techniques, tools, etc there will always be a disparity. It was kind of sad to see just how much of the structure was lighter stone that had been replaced in modern times. I especially liked seeing small scale reproductions of the pediments and the layouts of these locations. There’s no way to know what being in these spaces would have actually felt like, but the repro’s were helpful for orienting and imagination. -

The Pseudo-Kufic Ornament and the Problem of Cross-Cultural Relationships Between Byzantium and Islam

The pseudo-kufic ornament and the problem of cross-cultural relationships between Byzantium and Islam Silvia Pedone – Valentina Cantone The aim of the paper is to analyze pseudo-kufic ornament Dealing with a much debated topic, not only in recent in Byzantine art and the reception of the topic in Byzantine times, as that concerning the role and diffusion of orna- Studies. The pseudo-kufic ornamental motifs seem to ment within Byzantine art, one has often the impression occupy a middle position between the purely formal that virtually nothing new is possible to add so that you abstractness and freedom of arabesque and the purely have to repeat positions, if only involuntarily, by now well symbolic form of a semantic and referential mean, borrowed established. This notwithstanding, such a topic incessantly from an alien language, moreover. This double nature (that gives rise to questions and problems fueling the discussion is also a double negation) makes of pseudo-kufic decoration of historical and theoretical issues: a debate that has been a very interesting liminal object, an object of “transition”, going on for longer than two centuries. This situation is as it were, at the crossroad of different domains. Starting certainly due to a combination of reasons, but ones hav- from an assessment of the theoretical questions raised by ing a close connection with the history of the art-historical the aesthetic peculiarities of this kind of ornament, we discipline itself. In the present paper our aim is to focus on consider, from this specific point of view, the problem of a very specific kind of ornament, the so-called pseudo-kufic the cross-cultural impact of Islamic and islamicizing formal inscriptions that rise interesting pivotal questions – hither- repertory on Byzantine ornament, focusing in particular on to not so much explored – about the “interference” between a hitherto unpublished illuminated manuscript dated to the a formalistic approach and a functionalistic stance, with its 10th century and held by the Marciana Library in Venice. -

Scr Tr Kap Tasmali

From the collections of the Istanbul Archaeological Museums Head of a kouros seventh–sixth century BC, marble, Samos 1645 T, date of accession unknown Indigenous Archaeologies in Ottoman Greece yannis hamilakis In recent years the links between the emergence of professional archaeology and the discourses and practices of western modernity have been explored in a number of publications and debates.1 However interesting and fruitful this discussion may be, it is carried out within a framework that assumes both a linear, developmental, evolutionist narrative for the discipline and a singular notion of modernity and of archaeology. Conventional narratives assume that archaeology developed, initially in the west in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, as part of the regime of modernity and out of earlier practices such as antiquarianism. But this is a problematic narrative that ignores nonelite, local, indigenous engagements with the material past, which predate the development of professionalized, official archaeology.2 In this essay I make a distinction between a modernist professional and institutionalized archaeol- ogy (which, much like modernity, can adopt diverse forms and expressions) and indigenous archaeologies: local, vernacular discourses and practices involv- ing things from another time. These phenomena have been recorded in travel writings and folktales, and can also be seen in the practices of reworking the material past, such as those represented by spolia; we need not romanticize, idealize, or exoticize them to see that they constitute alternative engagements with materiality and temporality, which can teach us a great deal. My context is Ottoman Greece, primarily in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, but with occasional references to earlier and later periods (fig. -

Download Pdf Here

Heaven & Earth EDITED BY ANASTASIA DRANDAKI DEMETRA PAPANIKOLA-BAKIRTZI ANASTASIA TOURTA HELLENIC REPUBLIC BENAKI MINISTRY OF CULTURE AND SPORTS MUSEUM national gallery of art ATHENS 2013 The catalogue is issued in conjunction with the exhibition Heaven and Earth: Art of Byzantium from Greek Collections, held at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, from October 6, 2013, through March 2, 2014, and at the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, from April 9 through August 25, 2014. The exhibition was organized by the Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports, Athens, with the collaboration of the Benaki Museum, Athens, and in association with the National Gallery of Art, Washington, and the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles. EXHIBITION CATALOGUE GREECE Editors ANASTASIA DRANDAKI, DEMETRA PAPANIKOLA-BAKIRTZI, ANASTASIA TOURTA General Coordination MARIA ANDREADAKI-VLAZAKI Benaki Museum research team PANOREA BENATOU, ELENI CHARCHARE, Exhibition concept–Curators JENNY ALBANI, EUGENIA CHALKIA, ANASTASIA DRANDAKI, MANDY KOLIOU, MARA VERYKOKOU DEMETRA PAPANIKOLA-BAKIRTZI, ANASTASIA TOURTA Bibliography CONSTANTINA KYRIAZI Supervision JENNY ALBANI, ANASTASIA DRANDAKI Translators from Greek Entries: MARIA XANTHOPOULOU Research assistant MANDY KOLIOU Essays: DEBORAH KAZAZI, VALERIE NUNN Packaging and Trasportation MOVEART SA Translator from French ELISABETH WILLIAMS Coordination BYZANTINE AND CHRISTIAN MUSEUM, ATHENS Text Editor RUSSELL STOCKMAN Financial Management DIMITRIS DROUNGAS Photographs of the exhibits VELISSARIOS VOUTSAS, ELPIDA BOUBALOU USA Photographs of Mount Athos exhibits GEORGE POUPIS Designer FOTINI SAKELLARI NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART Map PENELOPE MATSOUKA Curator SUSAN MACMILLAN ARENSBERG Color separations PANAYOTIS VOUVELIS, STRATOS VEROPOULOS Exhibitions D. DODGE THOMPSON, NAOMI REMES, DAVID HAMMER Printing ADAM EDITIONS-PERGAMOS Design and Installation MARK LEITHAUSER, JAME ANDERSON, BARBARA KEYES Printed on Fedrigony 150 gsm Registrar MICHELLE FONDAS Conservation BETHANN HEINBAUGH, KIMBERLY SCHENCK Education FAYA CAUSEY, HEIDI HINISH J. -

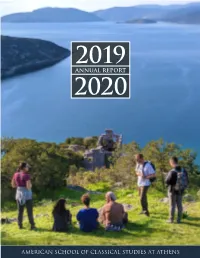

2019–2020 ASCSA Annual Report

| 1 2019 ANNUAL REPORT 2020 AMERICAN SCHOOL OF CLASSICAL STUDIES AT ATHENS 2 | Above: The Stoa of Attalos and Parthenon at sunrise Cover: Regular Members enjoy a spectacular view of Siphai on the Gulf of Corinth | 3 AMERICAN SCHOOL OF CLASSICAL STUDIES AT ATHENS 139TH ANNUAL REPORT | 2019–2020 c 5 MESSAGE FROM THE BOARD PRESIDENT, MANAGING COMMITTEE CHAIR, AND DIRECTOR 6 ACADEMIC PROGRAMS 10 ARCHAEO LOGICAL FIELDWORK 15 RESEARCH FACILITIES 21 PUBLICATIONS 23 OUTREACH 25 PHILANTHROPY AND PUBLIC ENGAGEMENT 30 HONORS AND AWARDS 31 LECTURES AND EVENTS 33 GOVERNANCE 34 STAFF, FACULTY, AND MEMBERS OF THE SCHOOL 39 COOPERATING INSTITUTIONS 43 DONORS 47 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS Q and g indicate special digital content. Please click these links to view the media. The4 | Acropolis at sunrise ABOUT THE AMERICAN SCHOOL OF CLASSICAL STUDIES AT ATHENS Founded in 1881, the American School of Classical Studies at Athens is the oldest and largest U.S. overseas research institution. A consortium of nearly 200 North American colleges and universities, the School provides graduate students and scholars a base for the advanced study of all aspects of Greek culture, from antiquity to the present day. The School remains, as its founders envisioned, primarily a privately funded, nonprofit educational and cultural center dedicated to preserving and promoting Greece’s rich heritage. The mission of the School is to advance knowledge of Greece (and related Mediterranean areas) in all periods by training young scholars, sponsoring and promoting archaeological fieldwork, providing resources for scholarly work, and disseminating research. The School is also charged by the Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports with primary responsibility for all American archaeological research in the country and is actively engaged in supporting the investigation, preservation, and presentation of Greece’s cultural heritage. -

Journals of a Landscape Painter in Albania, &C

W M'f-ff sA* JOURNALS OT \ LANDSCAPE PAINTER IN ALBANIA. &c BY EDWARD LEAR A A \ w LONDON: RICHARD BENTLEY. $u&Its!)ct fu ©rtjfnavo to %]n fHajesttr. 01 • I don: Printci clnilze and Co., 13, Poland Street. LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS. MAP To face YENinjK VODHEXA MO.V A STIR A KM Rill II A TYRANA KROIA sk<5dra DURAZZO BERAT KHIMARA AVLONA TEPELKNT ARGHYROKASTRO IOANNIXA NICOPOLIS ART A SULI PARGA METEOR A TKMPE INTRODUCTION. The following Notes were written during two journeys through part of Turkey in Europe:—the first, from Saloniki in a north-western direction through ancient Macedonia, to Illyrian Albania, and by the western coast through Epirus to the northern boundary of modern Greece at the Gulf of Arta : —the second, in Epirus and Thessaly. Since the days of Gibbon, who wrote of Albania, — "a country within sight of Italy less known than the interior of America,"— much has been done for the topography of these and those who wish for a clear regions ; insight into their ancient and modern defini- tions, are referred to the authors who, in the present century, have so admirably investigated and so admirably illustrated the subject. For neither the ability of the writer of these B 1 2 l\ I R0D1 i 1 1 of journals, nor their -cope, permil an) attempt to follow in track of those on his pari the learned travellers: enough if he may avail himself of their Labours by quotation where such aid is necessary throughout his memo- randa <»!' an artist's mere tour of search among the riches of far-away Landscape. -

Eurasian Decorative Animal Features of 'The Little

AAkinkin TTunceruncer Istanbul University EURASIAN DECORATIVE ANIMAL FEATURES OF ‘THE LITTLE METROPOLIS CHURCH OF ATHENS’ he Byzantine Empire and Turkish states co-existed in Anatolia and the Mediterranean basin for a long period of time, during which the Tcivilizations directly or indirectly influenced each other in culture and the arts. ‘The Little Metropolis Church of Athens’, also known as ‘Hagios Eleutherios Church’, has a cross-in-square plan and its structure is dated to the end of the 12th century.1) The building is characterised by the heavy use of spoila in its construction. Many of the materials used belong to antiquity and the early Christian era.2) The building contains quite a rich variety of floral and figurative decorations thanks to the spolia materials used in the exterior. Reliefs depicting an antique festival, supernatural, fantastic, animal figures, one-on-one animal fight scenes and animal and human figures, decorate the entire outer surface of the structure. However, it is the symmetrical lion figures positioned on both sides of a cross, placed above the entrance door in the axis of the main apse, and a depiction of a lion-deer fight on the abscissa front, which are of significance for Turkish art. A rectangular framed panel, bordered with geometric fittings, presumably made from spolia, on the left-hand side, in the direction of the church’s apse, contains a composition of a lion and deer struggle on a background decorated with floral motifs. The depiction shows the lion on the deer, with its claws sunk into the deer’s body, biting it from behind. -

Looking at the Past of Greece Through the Eyes of Greeks Maria G

Looking at the Past of Greece through the Eyes of Greeks Maria G. Zachariou 1 Table of Contents Introduction 00 Section I: Archaeology in Greece in the 19th Century 00 Section II: Archaeology in Greece in the 20th Century 00 Section III: Archaeology in Greece in the Early 21st Century 00 Conclusion: How the Economic Crisis in Greece is Affecting Archaeology Appendix: Events, Resources, Dates, and People 00 2 Introduction The history of archaeology in Greece as it has been conducted by the Greeks themselves is too major an undertaking to be presented thoroughly within the limits of the current paper.1 Nonetheless, an effort has been made to outline the course of archaeology in Greece from the 19th century to the present day with particular attention to the native Greek contribution. The presentation of the historical facts and personalities that played a leading and vital role in the formation of the archaeological affairs in Greece is realized in three sections: archaeology in Greece during the 19th, the 20th, and the 21st centuries. Crucial historical events, remarkable people, such as politicians and scholars, institutions and societies, are introduced in chronological order, with the hope that the reader will acquire a coherent idea of the evolution of archaeology in Greece from the time of its genesis in the 19th century to the present. References to these few people and events do not suggest by any means that there were not others. The personal decisions and scientific work of native Greek archaeologists past and present has contributed significantly to the same goal: the development of archaeology in Greece. -

Time and Religion in Hellenistic Athens: an Interpretation of the Little Metropolis Frieze

Time and Religion in Hellenistic Athens: An Interpretation of the Little Metropolis Frieze. Monica Haysom School of History, Classics and Archaeology Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Newcastle University, November 2015. ABSTRACT Two stones that form a part of the spolia on the Little Metropolis church (Aghios Eleutherios) in central Athens consist of a frieze depicting a calendar year. The thesis begins with a Preface that discusses the theoretical approaches used. An Introduction follows which, for reference, presents the 41 images on the frieze using the 1932 interpretation of Ludwig Deubner. After evaluating previous studies in Chapter 1, the thesis then presents an exploration of the cultural aspects of time in ancient Greece (Chapter 2). A new analysis of the frieze, based on ancient astronomy, dates the frieze to the late Hellenistic period (Chapter 3); a broad study of Hellenistic calendars identifies it as Macedonian (Chapter 4), and suggests its original location and sponsor (Chapter 5). The thesis presents an interpretation of the frieze that brings the conclusions of these chapters together, developing an argument that includes the art, religion and philosophy of Athenian society contemporary with the construction of the frieze. Given the date, the Macedonian connection and the link with an educational establishment, the final Chapter 6 presents an interpretation based not on the addition of individual images but on the frieze subject matter as a whole. This chapter shows that understanding the frieze is dependent on a number of aspects of the world of artistic connoisseurship in an elite, educated audience of the late Hellenistic period. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Material

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Material Memory: The Church of St. John in Keria, Mani A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Art History by Nicolyna Marie Enriquez 2019 ã Copyright by Nicolyna Marie Enriquez 2019 ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS Material Memory: The Church of St. John in Keria, Mani by Nicolyna Marie Enriquez Master of Arts in Art History University of California, Los Angeles, 2019 Professor Sharon Elizabeth Gerstel, Chair The Mesa or Inner Mani lies at the southernmost point of the Mani peninsula of Greece. In this region, stone structures, medieval and modern, domestic and ecclesiastical, are barely distinguishable from their rocky surroundings. Stone, quarried in this region from antiquity through the Byzantine period, was used both as building material and as carved ornamentation for churches and homes. When carved for use in a church, stone held particular importance for the families and communities that banded together to support the construction. This symbolic value can be seen in its reuse, over generations, in local churches. While many buildings incorporate the remains of decorative sculpture to enliven wall surfaces, one church in the region, St. John in Keria, which incorporates an unusually large number of ancient and medieval dressed stone and carved reliefs, forms the basis of this thesis. ii The thirteenth-century church of St. John is one of four churches in the modern village of Keria. Sculpted reliefs from earlier buildings, both ancient and medieval, are immured on the west, south and north walls of the church. Columns, capitals and carved relief sculpture are also in second use inside the church.