The Composition of APC Across Different Fields of Sciences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Physicochemical Perspective of Aging from Single-Cell Analysis Of

TOOLS AND RESOURCES A physicochemical perspective of aging from single-cell analysis of pH, macromolecular and organellar crowding in yeast Sara N Mouton1, David J Thaller2, Matthew M Crane3, Irina L Rempel1, Owen T Terpstra1, Anton Steen1, Matt Kaeberlein3, C Patrick Lusk2, Arnold J Boersma4*, Liesbeth M Veenhoff1* 1European Research Institute for the Biology of Ageing, University of Groningen, University Medical Center Groningen, Groningen, Netherlands; 2Department of Cell Biology, Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, United States; 3Department of Pathology, School of Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, United States; 4DWI-Leibniz Institute for Interactive Materials, Aachen, Germany Abstract Cellular aging is a multifactorial process that is characterized by a decline in homeostatic capacity, best described at the molecular level. Physicochemical properties such as pH and macromolecular crowding are essential to all molecular processes in cells and require maintenance. Whether a drift in physicochemical properties contributes to the overall decline of homeostasis in aging is not known. Here, we show that the cytosol of yeast cells acidifies modestly in early aging and sharply after senescence. Using a macromolecular crowding sensor optimized for long-term FRET measurements, we show that crowding is rather stable and that the stability of crowding is a stronger predictor for lifespan than the absolute crowding levels. Additionally, in aged cells, we observe drastic changes in organellar volume, leading to crowding on the *For correspondence: micrometer scale, which we term organellar crowding. Our measurements provide an initial [email protected] framework of physicochemical parameters of replicatively aged yeast cells. (AJB); [email protected] (LMV) Competing interest: See Introduction page 19 Cellular aging is a process of progressive decline in homeostatic capacity (Gems and Partridge, Funding: See page 19 2013; Kirkwood, 2005). -

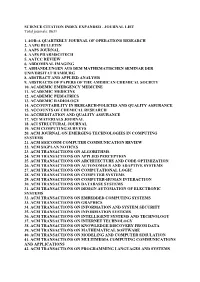

SCIENCE CITATION INDEX EXPANDED - JOURNAL LIST Total Journals: 8631

SCIENCE CITATION INDEX EXPANDED - JOURNAL LIST Total journals: 8631 1. 4OR-A QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF OPERATIONS RESEARCH 2. AAPG BULLETIN 3. AAPS JOURNAL 4. AAPS PHARMSCITECH 5. AATCC REVIEW 6. ABDOMINAL IMAGING 7. ABHANDLUNGEN AUS DEM MATHEMATISCHEN SEMINAR DER UNIVERSITAT HAMBURG 8. ABSTRACT AND APPLIED ANALYSIS 9. ABSTRACTS OF PAPERS OF THE AMERICAN CHEMICAL SOCIETY 10. ACADEMIC EMERGENCY MEDICINE 11. ACADEMIC MEDICINE 12. ACADEMIC PEDIATRICS 13. ACADEMIC RADIOLOGY 14. ACCOUNTABILITY IN RESEARCH-POLICIES AND QUALITY ASSURANCE 15. ACCOUNTS OF CHEMICAL RESEARCH 16. ACCREDITATION AND QUALITY ASSURANCE 17. ACI MATERIALS JOURNAL 18. ACI STRUCTURAL JOURNAL 19. ACM COMPUTING SURVEYS 20. ACM JOURNAL ON EMERGING TECHNOLOGIES IN COMPUTING SYSTEMS 21. ACM SIGCOMM COMPUTER COMMUNICATION REVIEW 22. ACM SIGPLAN NOTICES 23. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON ALGORITHMS 24. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON APPLIED PERCEPTION 25. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON ARCHITECTURE AND CODE OPTIMIZATION 26. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON AUTONOMOUS AND ADAPTIVE SYSTEMS 27. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON COMPUTATIONAL LOGIC 28. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON COMPUTER SYSTEMS 29. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON COMPUTER-HUMAN INTERACTION 30. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON DATABASE SYSTEMS 31. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON DESIGN AUTOMATION OF ELECTRONIC SYSTEMS 32. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON EMBEDDED COMPUTING SYSTEMS 33. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON GRAPHICS 34. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON INFORMATION AND SYSTEM SECURITY 35. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON INFORMATION SYSTEMS 36. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON INTELLIGENT SYSTEMS AND TECHNOLOGY 37. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON INTERNET TECHNOLOGY 38. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON KNOWLEDGE DISCOVERY FROM DATA 39. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON MATHEMATICAL SOFTWARE 40. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON MODELING AND COMPUTER SIMULATION 41. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON MULTIMEDIA COMPUTING COMMUNICATIONS AND APPLICATIONS 42. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON PROGRAMMING LANGUAGES AND SYSTEMS 43. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON RECONFIGURABLE TECHNOLOGY AND SYSTEMS 44. -

Journal List Emerging Sources Citation Index (Web of Science) 2020

JOURNAL TITLE ISSN eISSN PUBSLISHER NAME PUBLISHER ADDRESS 3C EMPRESA 2254‐3376 2254‐3376 AREA INNOVACION & DESARROLLO C/ELS ALZAMORA NO 17, ALCOY, ALICANTE, SPAIN, 03802 3C TECNOLOGIA 2254‐4143 2254‐4143 3CIENCIAS C/ SANTA ROSA 15, ALCOY, SPAIN, 03802 3C TIC 2254‐6529 2254‐6529 AREA INNOVACION & DESARROLLO C/ELS ALZAMORA NO 17, ALCOY, ALICANTE, SPAIN, 03802 3D RESEARCH 2092‐6731 2092‐6731 SPRINGER HEIDELBERG TIERGARTENSTRASSE 17, HEIDELBERG, GERMANY, D‐69121 3L‐LANGUAGE LINGUISTICS LITERATURE‐THE SOUTHEAST ASIAN JOURNAL OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE STUDIES 0128‐5157 2550‐2247 PENERBIT UNIV KEBANGSAAN MALAYSIA PENERBIT UNIV KEBANGSAAN MALAYSIA, FAC ECONOMICS & MANAGEMENT, BANGI, MALAYSIA, SELANGOR, 43600 452 F‐REVISTA DE TEORIA DE LA LITERATURA Y LITERATURA COMPARADA 2013‐3294 UNIV BARCELONA, FACULTAD FILOLOGIA GRAN VIA DE LES CORTS CATALANES, 585, BARCELONA, SPAIN, 08007 AACA DIGITAL 1988‐5180 1988‐5180 ASOC ARAGONESA CRITICOS ARTE ASOC ARAGONESA CRITICOS ARTE, HUESCA, SPAIN, 00000 AACN ADVANCED CRITICAL CARE 1559‐7768 1559‐7776 AMER ASSOC CRITICAL CARE NURSES 101 COLUMBIA, ALISO VIEJO, USA, CA, 92656 A & A PRACTICE 2325‐7237 2325‐7237 LIPPINCOTT WILLIAMS & WILKINS TWO COMMERCE SQ, 2001 MARKET ST, PHILADELPHIA, USA, PA, 19103 ABAKOS 2316‐9451 2316‐9451 PONTIFICIA UNIV CATOLICA MINAS GERAIS DEPT CIENCIAS BIOLOGICAS, AV DOM JOSE GASPAR 500, CORACAO EUCARISTICO, CEP: 30.535‐610, BELO HORIZONTE, BRAZIL, MG, 00000 ABANICO VETERINARIO 2007‐4204 2007‐4204 SERGIO MARTINEZ GONZALEZ TEZONTLE 171 PEDREGAL SAN JUAN, TEPIC NAYARIT, MEXICO, C P 63164 ABCD‐ARQUIVOS -

The Genetic Code: Dissected International Journal of Biology And

International Journal of Biology and Genetics Research Article The Genetic Code: Dissected BOZEGHA WB* Numeration Science Literature, Development Research Project, Nigeria. Received: 04 January, 2021; Accepted: 08 January, 2021; Published: 15 January, 2021 *Corresponding Author: W.B.Bozegha, Numeration Science Literature, Development Research Project, Foubiri Sabagreia, Kolga, Bayelsa State, Nigeria. E-mail address: [email protected] Abstract Statement of the Problem: By genetic code, it is meant the true genetic code of 24 permutation quadruplets, which is a fabric segmented into quadruplet codons comprising the RNA four bases A,U,G,C (Adenine, Uracil, Guanine, Cytosine). Dissection is the gory experience of frogs and rabbits and the like of animals, when they become specimens, rather prisoners of war, in the hands of biologists and zoologists prosecuting anatomical studies in laboratories. To all intents and purposes the 24 quadruplet genetic code is now made such a specimen, though not in the hands of the traditional practitioners of dissection, but under a Numerationist from the perspective of Numeration as science of number and arrangement. Methodology and Theoretical Orientation: Bodies of the animal specimens under dissection are usually cut open with sharp instruments to expose their entrails for visual access in furtherance of anatomical studies. So the 24 quadruplet genetic code whose body is a segmented fabric or string of the RNA four bases A,U,G,C in diverse sequences called codons subjected to separation of its constituent nucleotide base types, though without cutting instruments, because they are amenable to dichotomization in terms of Purines and Pyrimidines. Findings: The 24 quadruplet genetic code is transformed into a two-winged creature upon dissection. -

Disentangling Gold Open Access

Forthcoming in Glanzel, W., Moed, H.F., Schmoch U., Thelwall, M. (2018). Springer Handbook of Science and Technology Indicators. Springer Disentangling Gold Open Access Daniel Torres-Salinas*, Nicolas Robinson-Garcia** and Henk F. Moed*** * Universidad de Granada (EC3metrics SL y Medialab-UGR) and Universidad de Navarra, Spain ** School of Public Policy, Georgia Institute of Technology, United States *** Visiting scholar, Universidad de Granada, Spain Abstract This chapter focuses on the analysis of current publication trends in gold Open Access (OA). The purpose of the chapter is to develop a full understanding on country patterns, OA journals characteristics and citation differences between gold OA and non-gold OA publications. For this, we will first review current literature regarding Open Access and its relation with its so-called citation advantage. Starting with a chronological perspective we will describe its development, how different countries are promoting OA publishing, and its effects on the journal publishing industry. We will deepen the analysis by investigating the research output produced by different units of analysis. First, we will focus on the production of countries with a special emphasis on citation and disciplinary differences. A point of interest will be identification of national idiosyncrasies and the relation between OA publication and research of local interest. This will lead to our second unit of analysis, OA journals indexed in Web of Science. Here we will deepen on journals characteristics and publisher types to clearly identify factors which may affect citation differences between OA and traditional journals which may not necessarily be derived from the OA factor. Gold OA publishing is being encouraged in many countries as opposed to Green OA. -

Stem Cells, Influenza, Pit Bulls, Darwin, and More

Editorial Top ten in Journal of Biology in 2009: stem cells, influenza, pit bulls, Darwin, and more Miranda Robertson This is a more or less frivolous look at the top ten most however feel able with reasonable confi dence to reject one accessed articles – of any kind – published in Journal of of the most important objections to the policy, which is that Biology this year. Frivolous, because the validity of any if authors are allowed to opt out of re-review of their revised conclusions drawn from this statistic is undermined by manuscripts reviewers may refuse to referee them. We have many considerations. The number of times an article is ac- had no refusals – although it is impossible to say whether cessed does not measure how many people actually read it, this means reviewers are content with the policy, or sim- nor, for most articles, is it any indication of how much it ply don’t read beyond the fi rst paragraph of the request to will be cited (itself an imperfect measure of importance): where the policy is explained. Probably both. it is most likely to refl ect what people think they want to read about. What else? Fifth most accessed, and again both topical and provocative, is Jonathan Howard’s Opinion on why Darwin Even then, there is the problem that more recently pub- didn’t discover Mendel’s laws [7]; and the two research pa- lished articles have had less time to accrue accesses; al- pers in the top ten, Chan et al. on conservation of gene ex- though by far the highest access rates occur in the fi rst three pression in vertebrate tissues [8] and Puigbo et al. -

Journal of Biology Celebrates Its Fifth Anniversary Biomedcentral

BioMed Central Editorial Journal of Biology celebrates its fifth anniversary Published: 29 June 2007 Journal of Biology 2007, 6:5 The electronic version of this article is the complete one and can be found online at http://jbiol.com/content/6/3/5 © 2007 BioMed Central Ltd Five years ago this month, Journal of have been cited and accessed. Publish- an article by Mark Noble and col- Biology was launched under the guid- ing on average only every two months leagues provided evidence that brain ance of Editor-in-Chief Martin Raff has its perils, however: both authors cells are susceptible to chemotherapy and Editor Theodora Bloom as the and readers told us that they’d be [10]; the article has been downloaded premier biology journal of the open happier to see a journal that wasn’t so more than 5,000 times from the access publisher BioMed Central, the very selective and published more Journal of Biology site with a flurry of publisher of Genome Biology and the often. The journal is now planning to media interest. BMC series of journals. As we cele- build on its success in publishing Of course, for many authors, brate Journal of Biology’s birthday, we high-quality articles and is striving to readers and institutions there is one take this opportunity to reflect on the increase the rate of publication, while measure that matters above all others first five years during which the maintaining a very high standard. in evaluating a journal: the impact journal has published articles of factor, as determined by The Thomson exceptional interest across the full Corporation (ISI). -

Ejbio: Electronic Journal of Biology Ming Chen

Ellectroniic Electronic Journal of Biology, 2005, Vol. 1(1): 1-2 eJBio: Electronic Journal of Biology Ming Chen Bielefeld University Electronic Journal of Biology (eJBio) is a peer- including speed of publication, wide distribution, and reviewed, all-electronic, biological journal available ease of access. More and more conventional print at no charge to readers via the Internet at journals now have electronic versions. We expect http://www.ejbio.com/. eJBio is, as far as we know, that this electronic journal will be in the same format the first e-journal specifically devoted to Chinese as that of standard ones. scientists to provide an academic publication A journal on the Web, provided with an efficient platform to communicate their biological research. Web and e-mail based reviewing process, should This editorial to the first volume of eJBio is to overcome these deficiencies and enhance the answer the following questions: distribution ad availability of scientific information throughout the worldwide scientific community. 1. Why a new journal? Articles are published as soon as they are accepted rather than waiting for an issue to be completed. Why a new journal on general biology at a time By publishing on the Internet, costs are when there is already a proliferation of related minimized, allowing free subscriptions to eJBio. journals and newsletters? Our answer is that it is Moreover, Authors can present data and results that not enough, especially for Chinese scientists. cannot readily be presented in print journals. This Existing journals do not meet the growing needs of includes color figures, with no extra charge. -

Bibliothèque Numérique De L'enssib

Bibliothèque numérique de l’enssib Integrating Europe! New partnerships across old borders, 29 juin au 2 juillet 2004 33e congrès LIBER The library as a virtual research environment VELTEROP, Jan BioMed Central VELTEROP, Jan. The library as a virtual research environment. In 33th LIBER Annual General Conference, Integrating Europe! New partnerships across old borders, Saint-Pétersbourg, du 29 juin au 2 juillet 2004 [en ligne]. Format PDF. Disponible sur : <http://www.enssib.fr/bibliotheque-numerique/notice-1410> Ce document est « tous droits réservés ». Il est protégé par le droit d’auteur et le code de la propriété intellectuelle. Il est strictement interdit de le reproduire, dans sa forme ou son contenu, totalement ou partiellement, sans un accord écrit de son auteur. L’ensemble des documents mis en ligne par l’enssib sont accessibles à partir du site : http://www.enssib.fr/bibliotheque-numerique/ BioBioMedMed CentralCentral OpenOpen AccessAccess isis justjust thethe beginningbeginning The view after 10,000 articles Jan Velterop, LIBER, St Petersburg, June 2004 manuscript Subscription model Publisher Author Reader $ $ publication $ publication Institution manuscript Open Access model Publisher Author Reader $ publication publication Institution Meteor struck Sender pays magazines Open Access journals Review jnls 2000’s Internet struck Recipient pays societies commercial 1900’s 1800’s Sender paid Subscription 1700’s journals Correspondence Recipient between researchers paid 1600’s BioBioMedMed CentralCentral FullFull PeerPeer ReviewReview -

Journal of Biology Education 8 (1) (2019) : 56-61

Saiman Rosamsi et al., / Journal of Biology Education 8 (1) (2019) : 56-61 J.Biol.Educ. 8 (1) (2019) Journal of Biology Education http://journal.unnes.ac.id/sju/index.php/ujbe Interactive Multimedia Effectiveness in Improving Cell Concept Mastery 1✉ 1 2 Saiman Rosamsi , Mieke Miarsyah , Rizhal Hendi Ristanto Master of Biology Education Progam, FMIPA, State Univesity of Jakarta Info articles Abstract History Articles: Received : January 2019 The learning process has been carried out in the conventional way, this is caused by the teacher's Accepted : March 2019 understanding of using multimedia is still not optimal, so the learning method used is still limited. This phenomenon makes the researchers interested in doing this research. The purpose of the Published : April 2019 study to determine the effectiveness of multimedia use in improving mastery of cell concepts. this Keywords: study uses a quantitative approach with a quasi-experimental method. This study uses a cell, interactive multimedia, quantitative approach with a quasi-experimental method. Based on the results of the study, it was mastery of concepts. found that the use of interactive multimedia provides a good value of effectiveness in mastering the concept of students cells, compared with learning using conventional media. This is evidenced by the t-test on SPSS obtained value t = 0.00. Based on these results the average value of the gain experimental class is greater, which is 41, compared to the average value of the gain control class, which is 32. The results of this study is indicate there are differences in learning by using interactive multimedia and learning with conventional media. -

NAAS Score of Science Journals (Effective from January 1, 2020)

NAAS Score of Science Journals (Effective from January 1, 2020) S.No. JrnID ISSN Name of Journal NAAS Score 1. A001 1532-8813 AATCC Review 6.36 2. A002 0889-325X ACI Materials Journal 7.45 3. A003 1944-8244 ACS Applied Materials and Interfaces 14.46 4. A004 1554-8929 ACS Chemical Biology 10.37 5. A005 2156-8952 ACS Combinatorial Science (Journal of Combinatorial Chemistry) 9.20 6. A006 1948-5875 ACS Medicinal Chemistry Letters 9.74 7. A007 1936-0851 ACS Nano 19.90 8. A008 2168-0485 ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering 12.97 9. A009 2277-9663 AGRES - An International e-Journal 3.65 10. A010 0001-1541 AIChE Journal 9.46 11. A011 0269-9370 AIDS 10.50 12. A012 2191-0855 AMB Express 8.23 13. A013 0949-1775 Accreditation and Quality Assurance 6.80 14. A014 0906-4702 Acta Agriculturae Scandinavica, Section A-Animal Science 6.69 15. A015 0906-4710 Acta Agriculturae Scandinavica, Section B-Soil and Plant Science 6.81 16. A016 0139-3006 Acta Alimentaria 6.55 17. A017 1672-9145 Acta Biochimica et Biophysica Sinica 8.50 18. A018 0236-5383 Acta Biologica Hungarica 6.68 19. A019 1742-7061 Acta Biomaterialia 12.64 20. A020 0102-3306 Acta Botanica Brasilica 7.11 21. A021 0365-0588 Acta Botanica Croatica 6.99 22. A022 1253-8078 Acta Botanica Gallica 6.00 23. A023 1233-2356 Acta Chromatographica 6.67 24. A024 1600-5368 Acta Crystallographica - E ** 25. A025 2053-2296 Acta Crystallographica, Section C-Structural Chemistry 6.93 26. -

Progress and Impact of Electronic Journal of Biology

Electronic Journal of Biology, 2020, Vol.16(3): 106-107 Progress and Impact of Electronic Journal of Biology Bilgin Kadri Aribas Department of Radiology, Bulent Ecevit University, The School of Medicine, 67600 Zonguldak, Turkey. *Corresponding author: Bilgin Kadri Aribas, Assistant Professor, Department of Radiology, Bulent Ecevit University, The School of Medicine, 67600 Zonguldak, Turkey, E-mail: [email protected] Citation: Aribas BK. Progress and Impact of Electronic Journal of Biology. Electronic J Biol. 16:3 Received: April 20, 2020; Accepted: April 30, 2020; Published: May 08, 2020 Editorial 1. General Overview 2.2 Scope Electronic Journal of Biology is an international Translation Biology Transcription is the first step prominent journal which published articles globally of gene expression, in which a particular segment in the prime field of Chemical biology, Physiology, of DNA is copied into RNA (mRNA) by the enzyme Biochemistry, Biomedical research, Synthetic RNA polymerase. Both RNA and DNA are nucleic biology, Molecular biology, Structural biology, acids, which use base pairs of nucleotides as a Ecology, Plant biology, Animal biology and other complementary language. Translation is the process related topics to the forefront of conceptual of translating the sequence of a messenger RNA developments in the discipline. It is an open access (mRNA) molecule to a sequence of amino acids and peer reviewed journal by eminent Editorial Board during protein synthesis. and the manuscripts are peer-reviewed by potential Conservation biology is the reviewers according to their research interest. Conservation Biology scientific study of the nature and of Earth′s biodiversity Electronic Journal of Biology offers easy to submit with the aim of protecting species, their habitats, and review systems.