Analytical Study on Optimal Administrative-Territorial Structure for Republic of Moldova

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

De Intenlie Ln Vederea Initierii Cooperirii Intercomunale

L- REPUBLICA MOLDOVA MEMORANDUM de intenlie ln vederea initierii cooperirii intercomunale incheiat astdzi 1 Decembrie 2020, in Municipiul Ungheni Pdrlile: Municipiul Ungheni, reprezentat de primar Dl Alexandru Ambros Oragul Corneqti, reprezentat de primar Dna Buga Vera Comuna Agronomovca, reprezentati de primar Dl Grosu Vasile Comuna Alexeevca, reprezentatd de primar Dl Bujor Vitalie Comuna Boghenii Noi, reprezentatd de primar Dl Filipovici Gheorghe Comuna Buciumeni, reprezentatd de primar Dl Petriciuc Filip Satul Bumbdta, reprezentat de primar Dl Paladi Dumitru Satul Bugila, reprezentat de primar Dl V?rlan lgor Satul Cetireni, reprezentat de primar Dna Dicusar Ana Satul Chirileni, reprezentat de primar Dl Stoica lurie Comuna Cioropcani, reprezentatd de primar Dl Robule( Victor Comuna Condrdtegti, reprezentatii de primar Dl Zgureanu $tefan Satul Cornegti, reprezentat de primar Dl Morari Valeriu Satul Cornova, reprezentat de primar Dl Rogca $tefan Satul Costuleni, reprezentat de primar Dl Andrei Rudicov Comuna Flori[oaia Veche, reprezentatd de primar Dl Mdrgdrint Sergiu Comuna Hircegti , teprezentatd de primar Dna Sirbu Tatiana Comuna Mdciregti, reprezentatd de primar Dl Manciu Sergiu Satul Mdgurele, reprezentat de primar Dl Caldare Andrei Comuna Mdnoilegti, reprezentatd de primar Dna Grosu Valentina Comuna Morenii Noi, reprezentatd de primar Dna Lincovscaia Valentina Satul Ndpddeni, reprezentat de primar Dna Arteomov Maria Comuna Negurenii Vechi, reprezentatd de primar Dl Cozariuc Adrian Comuna Petregti, reprezentatd de primar Dl Gorea -

Raionul Căușeni Responsabil Tehnic: Beril Valeriu, Telefon De

Programul de reparație periodică/întreținere a drumurilor naționale, locale, comunale și străzi pe anul 2020 (finanțat din Bugetul de Stat), pentru raionul Căușeni Antreprenor: S.R.L.,,Dromas-Cons”, Contract nr. 06-14/279 din 13.07.2020 Responsabil tehnic: Beril Valeriu, Telefon de contact: 068041112 Lungimea planificată, (km) Planificarea lucrărilor Executarea lucrărilor Volum Beton asfaltic Macadam alocatiilor, Valoarea Executarea Nr. Denumirea drumului Raion/localitate HG 314 din obiectivului, Începutul Începutul lucrărilor crt. Sfîrșitul lucrărilor Sfîrșitul lucrărilor 20.05.2020 (lei) lucrărilor lucrărilor (foto) km tip km tip (mii lei) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Raionul Căușeni 1 str.Pacii s. Baccealia 0,940 2 779 723,42 2 str. Sadoveanu s. Baccealia 0,135 2 1 298,0 112 096,93 31.07.2020 27.09.2020 11.08.2020 29.09.2020 Foto 3 str. A. Mateevici s. Baccealia 0,465 2 385 779,00 4 Str. Școlii s. Baimaclia 0,346 4 1 113,0 1 080 170,37 27.07.2020 31.07.2020 01.09.2020 05.09.2020 Foto 5 str. Ciaga s. Chircăieştii Noi 0,577 2 546 938,64 1 113,0 31.07.2020 29.09.2020 15.10.2020 04.11.2020 Foto 6 str. Independenței s. Chircăieştii Noi 0,577 2 546 938,64 7 str. Serghei Lazo s. Cîrnăţenii Noi 1,008 2 836 057,34 27.07.2020 05.08.2020 1 113,0 31.07.2020 30.09.2020 Foto 8 str. Ion Creangă s.Salcuța Nouă, com. -

Activity Details Activity Name Local Development in Taraclia District

Activity Details Activity name Local Development in Taraclia District AMP ID 872111668453 Objectives Two main interventions are envisaged: Installation of 8 water stations in different local communities serving over 30,000 people and renovation of the roof for the dormitory of Taraclia University. These two projects were assessed to have a significant impact for the local population responding directly to their pressing development needs. Description The water project is directly aligned to the Taraclia district Programme for 2013-2015 towards solving the issue of access to clean water as approved by the district council from November 2013. The project envisages the installation of 8 water stations, which represent special installation allowing access to clean filtered water. Eight localities have been identified to be in most critical needs of such objects, they being: Taraclia town- 13,500 people Tvardita town – 6,082 people Valea Perjei village – 4,982 people Corten village- 3,314 people Cairaclia village – 2,005 people Albota de Jos village – 1,315 people Albota de Sus village – 912 people Cortenul Nou village, Cealic – 250 people The second intervention refers to the roof renovation at Grigore Tsamblak University in Taraclia. The dormitory of the Grigore Tsamblak University is a five-storied building put into commission in 1983. The roof is a flat one and is covered with bitumen membranes. The dormitory has a capacity to accommodate 400 students. At present, it accommodates 180 students. The building has all the plumbing and wiring needed for a student dormitory. The building is located in the central part of Taraclia town and is intercalated into a fairly developed economic-social infrastructure. -

Anexa Nr. 1 La Hotărîrea Comisiei Electorale Centrale Nr. 2573 Din 16 August 2019

Anexa nr. 1 la hotărîrea Comisiei Electorale Centrale nr. 2573 din 16 august 2019 Denumirea unității Numărul de mandate de Nr. Numărul de locuitori la administrativ-teritoriale de consilier în consiliile d/o situația din 01.01.2019 nivelul al doilea municipale/raionale 1. municipiul Chișinău 779339 51 2. municipiul Bălți 127192 35 3. raionul Anenii Noi 80844 33 4. raionul Basarabeasca 26797 27 5. raionul Briceni 72733 33 6. raionul Cahul 115390 35 7. raionul Cantemir 57342 33 8. raionul Călărași 71072 33 9. raionul Căuşeni 85574 33 10. raionul Cimișlia 55252 33 11. raionul Criuleni 73101 33 12. raionul Dondușeni 40635 27 13. raionul Drochia 80378 33 14. raionul Dubăsari 35035 27 15. raionul Edineț 78183 33 16. raionul Fălești 84465 33 17. raionul Florești 80836 33 18. raionul Glodeni 54709 33 19. raionul Hînceşti 112544 35 20. raionul Ialoveni 98946 33 21. raionul Leova 49488 27 22. raionul Nisporeni 58313 33 23. raionul Ocnița 51754 33 24. raionul Orhei 109644 35 25. raionul Rezina 46772 27 26. raionul Rîșcani 62451 33 27. raionul Sîngerei 83076 33 28. raionul Soroca 92817 33 29. raionul Strășeni 87809 33 30. raionul Șoldănești 38184 27 31. raionul Ștefan Vodă 64944 33 32. raionul Taraclia 38794 27 33. raionul Telenești 65101 33 34. raionul Ungheni 105524 35 Anexa nr. 2 la hotărîrea Comisiei Electorale Centrale nr. 2573 din 16 august 2019 Numărul de mandate de Denumirea unității Numărul de locuitori Nr. consilier în consiliile administrativ-teritoriale de la situația din d/o sătești (comunale), nivelul întîi 01.01.2019 orășenești și municipale Municipiul Chișinău 1. -

Lista Lucrărilor Similare Executate

or.Nisporeni str.Tirgului 7 MD-6401 S.R.L. ''Nica'' Tel/fax: 0264 2 46 47 e-mail: [email protected] Formularul F3.10 Lista lucrărilor similare executate Numele clientului şi Genul de lucrări exe-cutate şi Preţul contractului Numele proiectului şi localitatea persoana de contact anul finisării lei SKAT Elveţia Staţie de Epurare cu ZUC din s.Iurceni,r.Nisporeni Construcţie capitală 2011 2.343.000 Bordeianu Grigore Primăria Cioreşti Reparaţia capitală a casei de cultură din s.Cioreşti Reparaţie capitală 2012 1.718.105 Guţu Valeriu Lucrări de reparaţie la grădiniţa de copii din s.Iurceni Primăria Iurceni Reparaţie capitală 2011 121.442 Secţ.Cult. Nisporeni Renovarea acoperişului la biblioteca orăşenească Nisporeni Renovarea acoperişului 2011 279.998 Andronachi Aurelia Primăria Boldureşti Renovarea acoperişului grădiniţei de copii s.Boldureşti Renovarea 2012 acoperişului 630.502 Miron Vasilie Primăria s.Ciuteşti Reparaţia grădiniţei de copii din s.Ciuteşti,r.Nisporeni Reparaţie capitală 2012 657.116 Iurie Stamati Primăria Şendreni Lucrări de reparaţie a Casei de cultură s.Şendreni Reparaţie 2011 240.000 Gorceag Chiril Primăria s.Ciuteşti 145.230 Reparaţia cazangeriei Gimnaziului din s.Ciuteşti,rnul Nisporeni Reparaţie capitală 2012 Iurie Stamati Reparaţia sistemului de încălzire şi iluminare la Grădiniţa de copii din Primăria Boldureşti Reparaţie capitală 2012 99.207 s.Boldureşti,rnul Nisporeni Miron Vasilie Construcţia sistemului de alimentare cu apă a satului Fundaţia SKAT Construcţie capitală 2013 2.554.490 Bolţun,raion.Nisporeni Jonathan Hecke Casa de locuit destinata serviciului Casa A.O.Keystone Human Services Reparatii capitale 2013 487.636 Comunitara din or.Nisporenistr.31August InternationalMoldova Association Lucrari de reparatie la oficiul medicilor de familie s.Ciutesti IMSP CMF Nisporeni Reparatii capitale 2013 119.950 r-nul Nisporeni Primaria com. -

10 Ri~ for Human Development

INTERNATIONAL PARTNERSHIP 10 RI~ FOR HUMAN DEVELOPMENT 26F Plaza Street, N E , Leesburg, Virgnia 20176, U S A. WINTER HEAT ASSISTANCE PROGRAM MOLDOVA USAID AGREEMENT NO. 121-A-00-99-00707-00 FINAL REPORT June 30, 1999 Tel (703) 443-2078, Fax. (703) 443-2012, E-mad mhd@erols corn TABLE OF CONTENTS Page # Report of Fuel Dellveries 1. Institutions which recelve fuel A. Hospitals ..... ....... 1 B. Boarding Schools & Orphanages .... ...... 2 C. Boarding Schools for Dlsabled .... ...... 3 D. Secondary Schools .......................... 3 E. Nurseries . ............................ .... 21 F. Pensloners & Vulnerable Famllles ...... 21 G. Other ................................. .. 40 H, Total Delivered ....................... 40 I. Summary of Dellverles by Categories ...... 41 J. Coverage Agalnst Heatmg Requlrements .... 41 Repalrs to Heatlng Systems ........... 42 Monitoring .......... ....... 43 Problems & How Problems were Addressed ........... 45 Outstanding Issues .......... 46 Cooperation wlth GOM .......... 46 Unforessen Matters ....... 47 Descrlbe any Matters/Problems Concerning Fuel Deliveries/Fuel Companies ....... 47 Number of Outstanding Fuel Companies Vouchers to be Paid ...... ....... 47 Other Comments ........... ...... 48 ATTACHMENT 1 Fuel Deliveries to Instltutlons ATTACHMENT 2: Coal Dellverles by Dlstrlct GR/AS Coal & Heatlng 011 for Instltutlons ATTACHMENT 3: Coal Dellverles by Dlstrlct - AS Coal for Households ATTACHMENT 4: Beneflclarles ATTACHMENT 5: Fuel Purchases ATTACHMENT 6: Coal Dellverles by Month ATTACHMENT 7. Payments -

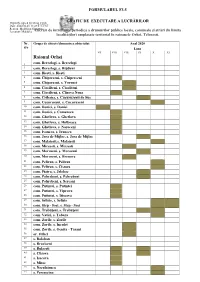

Raionul Orhei

FORMULARUL F3.5 GRAFIC DE EXECUTARE A LUCRĂRILOR Lucrări de întreținere periodică a drumurilor publice locale, comunale și străzi (în limita localităților) amplasate teritorial în raioanele Orhei, Telenesti. Nr. Grupa de obiecte/denumirea obiectului Anul 2020 d/o Luna VII VIII VIII IX X XI Raionul Orhei 1 com. Berezlogi, s. Berezlogi 2 com. Berezlogi, s. Hijdieni 3 com. Biesti, s. Biesti 4 com. Chiperceni, s. Chiperceni 5 com. Chiperceni, s. Voronet 6 com. Ciocilteni, s. Ciocilteni 7 com. Ciocilteni, s. Clisova Noua 8 com. Crihana, s. Cucuruzenii de Sus 9 com. Cucuruzeni, s. Cucuruzeni 10 com. Donici, s. Donici 11 com. Donici, s. Camencea 12 com. Ghetlova, s. Ghetlova 13 com. Ghetlova, s. Hulboaca 14 com. Ghetlova, s. Noroceni 15 com. Ivancea, s. Ivancea 16 com. Jora de Mijloc, s. Jora de Mijloc 17 com. Malaiesti,s. Malaiesti 18 com. Mirzesti, s. Mirzesti 19 com. Morozeni, s. Morozeni 20 com. Morozeni, s. Brenova 21 com. Pelivan, s. Pelivan 22 com. Pelivan, s. Cismea 23 com. Piatra, s. Jeloboc 24 com. Pohrebeni, s. Pohrebeni 25 com. Pohrebeni, s. Sercani 26 com. Putintei, s. Putintei 27 com. Putintei, s. Viprova 28 com. Putintei, s. Discova 29 com. Seliste, s. Seliste 30 com. Step - Soci, s. Step - Soci 31 com. Trebujeni, s. Trebujeni 32 com. Vatici, s. Tabara 33 com. Zorile, s. Zorile 34 com. Zorile, s. Inculet 35 com. Zorile, s. Ocnita - Tarani 36 or. Orhei 37 s. Bolohan 38 s. Braviceni 39 s. Bulaesti 40 s. Clisova 41 s. Isacova 42 s. Mitoc 43 s. Neculaieuca 44 s. Peresecina 45 s. -

Annual Report for Fy 2012

ANNUAL REPORT FOR FY 2012 Rule of Law Institutional Strengthening Program (ROLISP) USAID Contract No. AID-117-C-12-00002 Prepared by: Frederick G. Yeager COP Activity Office: USAID/Moldova COR: Ina Pislaru, September 30, 2012 Submitted October 15, 2012 by: Frederick G. Yeager, Chief of Party Checchi and Company Consulting, Inc. ROLISP Program 27 Armenesca Street 1 Chisinau, Moldova Contents FY 2012 ANNUAL REPORT ON EXPECTED RESUTS AND ACTIVITIES .............................................. 7 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................................. 8 OBJECTIVE 1: ENHANCE THE EFFECTIVENESS, TRANSPARENCY AND ACCOUNTABILITY OF THE MOLDOVAN JUDICIARY THROUGH STRENGTHENING THE CAPACITY OF THE SCM AND THE DJA .......................................... 8 OBJECTIVE 2: STRENGTHEN THE INSTITUTIONAL AND OPERATIONAL CAPACITY OF THE NIJ ........................... 11 • Modernize CLE Training Content ..................................................................................................... 13 • Develop guidelines for interpreting the ICMS statistical data .......................................................... 13 OBJECTIVE 3: INCREASE THE CAPACITY OF CIVIL SOCIETY ORGANIZATIONS TO MONITOR AND ADVOCATE FOR JUSTICE SECTOR REFORMS AND IMPROVE PUBLIC LEGAL AWARENESS THUS INCREASING ACCESS TO JUSTICE IN MOLDOVA ...................................................................................................................................... 14 PUBLIC-PRIVATE -

Raionul Drochia De Reparație Periodică/Īntreținere a Drumurilor

Programul de reparație periodică/întreținere a drumurilor naționale, locale, comunale și străzi pe anul 2020 (finanțat din Bugetul de Stat), pentru raionul Drochia Antreprenor: S.R.L.,,Magistrala-Nord”, Contract nr. 06-14/277 din 09.07.2020 Responsabil tehnic: Valeriu PÎNZARU, Telefon de contact: 069590151 Lungimea planificată, (km) Planificarea lucrărilor Executarea lucrărilor Volum Beton asfaltic Macadam alocatiilor, Valoarea Executarea Nr. Denumirea drumului Raion/localitate HG 314 din obiectivului, Începutul Începutul lucrărilor crt. Sfîrșitul lucrărilor Sfîrșitul lucrărilor 20.05.2020 (lei) lucrărilor lucrărilor (foto) km tip km tip (mii lei) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Raionul Drochia 1 str.Cichir Ion - Chișca Nina s. Baroncea 0,125 2 107 921,62 2 str.Lihodei Victor. - Cercovscaia Galina s. Baroncea 0,512 2 442 021,24 3 str. Cercovscaia Galina - Belogrivaia Ana s. Baroncea 0,312 2 269 358,10 1 113,0 01.10.2020 10.10.2020 01.12.2020 12.12.2020 Foto 4 str.Zara Olga - Ciornaia Nadeja s. Baroncea 0,215 1 88 060,32 5 str.Dragan N.- Belei A. s. Baroncea 0,145 1 59 383,26 6 str.Prisacari B. - Rusu N s. Baroncea 0,210 2 224 461,43 7 Str. Cerbari Gheorghe – Balan Simion s. Cotova 0,500 1 204 791,80 8 Str. Pelin Maria – Colța Snejana s. Cotova 0,300 1 93 694,97 9 Str. Niselschi Iurie – Martîniuc Vasile s. Cotova 0,300 1 93 694,97 10 Str. Pogodin Ivan – Rumega Marusica s. Cotova 0,600 1 187 392,01 26.08.2020 10.09.2020 Foto 11 Str. -

Mişcarea Naturală a Populaţiei Republicii Moldova În Anul 2014

Mişcarea naturală a populaţiei Republicii Moldova în anul 2014 Culegere statistică Естественное движение населения Республики Молдова в 2014 году Статистический сборник Chişinău, 2015 Culegerea statistică „Mişcarea naturală a populaţiei Republicii Moldova” este cea mai amplă publicaţie care cuprinde date statistice vizînd mişcarea naturală a populaţiei Republicii Moldova în anul 2014. Indicatorii principali sînt prezentaţi în profil teritorial. Informaţia include unele cazuri de înregistrare a actelor de stare civilă din partea stîngă a Nistrului şi mun.Bender. Publicaţia este elaborată de către Biroul Naţional de Statistică în baza datelor primite de la Ministerul Justiţiei (Serviciul Stare Civilă). Culegerea a fost publicată în cadrul proiectului de colaborare între Republica Cehă şi Republica Moldova „Suportul integrat pentru dezvoltarea statisticii demografice în Republica Moldova (2013-2015)”. Publicația este destinată cercului larg de utilizatori ai datelor statistice de nivel central şi local. _________________________________________________________________________________ Статистический сборник «Естественное движение населения Республики Молдова» является наиболее полным изданием, которое содержит статистическую информацию о естественном движении населения Республики Молдова в 2014 году. Основные показатели представлены в территориальном разрезе. Информация включает отдельные случаи регистрации актов гражданского состояния жителей левобережья Днестра и мун. Бендер. Публикация подготовлена Национальным бюро статистики на основе -

(MDL) Bacioi 792 849,95 Revaca 2 821,00 Cruzesti R. Chisinau Mun

Tranșa III – 89 grădinițe beneficiare Localitatea Achitat RO (MDL) Bacioi 792 849,95 Revaca 2 821,00 Cruzesti r. Chisinau mun. 1 500 000,00 Chisinau (mun.) r. Chisinau mun. 1 000 000,00 Chisinau (mun.) r. Chisinau mun. 1 000 000,00 Chisinau (mun.) r. Chisinau mun. 813 773,48 Chisinau (mun.) r. Chisinau mun. 785 408,11 Chisinau (mun.) r. Chisinau mun. 700 000,00 Chisinau (mun.) r. Chisinau mun. 1 399 999,92 Chisinau (mun.) r. Chisinau mun. 952 945,35 Chisinau (mun.) r. Chisinau mun. 999 846,36 Chisinau (mun.) r. Chisinau mun. 1 999 999,99 Geamana r. Anenii Noi 483 811,30 Cobusca Veche r. Anenii Noi 700 000,00 Carabetovca r. Basarabeasca 600 000,00 Balti (mun.) r. Balti mun. 294 478,85 Tataresti r. Cahul 1 200 000,00 Ursoaia r. Cahul 300 000,00 Gotesti r. Cantemir 450 000,00 Gotesti r. Cantemir 400 000,00 Gotesti r. Cantemir 99 988,35 Hanaseni r. Cantemir 300 000,00 Sipoteni r. Calarasi 4 898 361,78 Tocuz r. Causeni 686 934,66 Chircaiestii Noi r. Causeni 559 177,06 Porumbrei r. Cimislia 446 583,00 Boscana r. Criuleni 299 991,00 Criuleni (or.) r. Criuleni 1 499 775,50 Tirnova r. Donduseni 600 000,00 Rediul Mare r. Donduseni 2 000 000,00 Pelinia r. Drochia 981 699,71 Burghelea r. Falesti 699 961,77 Floresti (or.) r. Floresti 977 483,50 Marculesti (or.) r. Floresti 149 999,49 Gura Camencii r. Floresti 300 000,00 Napadova r. Floresti 265 000,00 Ghindesti (or.) r. -

Curtea De Conturi

Republica Moldova CURTEA DE CONTURI HOTĂRÎRE Nr. HCC32/2013 din 27.06.2013 privind Raportul auditului bugetelor şi gestionării patrimoniului public în anii 2011-2012 în cadrul autorităților publice locale din raionul Căușeni Publicat : 23.08.2013 în MONITORUL OFICIAL Nr. 182-185 art. 33 Data intrării în vigoare Curtea de Conturi, în prezența președintelui raionului Căușeni, dl Ion Ciontoloi, șefului Direcției Finanțe, dl Simion Buga, șefului Direcţiei Învăţămînt, dl Vasile Molodilo, șefului Inspectoratului Fiscal de Stat Căușeni, dl Mihail Iliev, viceprimarului or. Căușeni, dl Ion Guzun, primarilor: or. Căinari, dl Anatolie Nebunelea, c. Baccealia, dna Claudia Nenov, s. Ciuflești, dl Sergiu Pîrlog, c. Cîrnățenii Noi, dna Parascovia Antoniuc, s. Săiți, dl Valeriu Mustață, s. Sălcuța, dl Ion Novac, s. Taraclia, dl Vladimir Cucereavîi, călăuzindu-se de art. 2 alin.(1) și art. 4 alin.(1) lit. a) din Legea Curții de Conturi nr. 261-XVI din 05.12.2008[1], a examinat Raportul auditului bugetelor şi gestionării patrimoniului public în anii 2011-2012 în cadrul autorităților publice locale din raionul Căușeni. Misiunea de audit s-a realizat în temeiul art. 28, art. 30 alin.(4), art. 31 din Legea Curţii de Conturi nr. 261-XVI din 05.12.2008 şi în conformitate cu Programul activităţii de audit a Curţii de Conturi pe anul 2012, avînd drept scop verificarea: respectării de către autoritățile administrației publice locale din raionul Căușeni a prevederilor regulamentare în exercițiul bugetar; corespunderii procedurilor de evaluare, planificare și colectare a impozitelor și taxelor locale, precum și de planificare, executare și raportare a cheltuielilor bugetare cadrului normativ; administrării și integrității patrimoniului public.