The Salmon Rivers and Lochs of Scotland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Water Safety Policy in Scotland —A Guide

Water Safety Policy in Scotland —A Guide 2 Introduction Scotland is surrounded by coastal water – the North Sea, the Irish Sea and the Atlantic Ocean. In addition, there are also numerous bodies of inland water including rivers, burns and about 25,000 lochs. Being safe around water should therefore be a key priority. However, the management of water safety is a major concern for Scotland. Recent research has found a mixed picture of water safety in Scotland with little uniformity or consistency across the country.1 In response to this research, it was suggested that a framework for a water safety policy be made available to local authorities. The Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents (RoSPA) has therefore created this document to assist in the management of water safety. In order to support this document, RoSPA consulted with a number of UK local authorities and organisations to discuss policy and water safety management. Each council was asked questions around their own area’s priorities, objectives and policies. Any policy specific to water safety was then examined and analysed in order to help create a framework based on current practice. It is anticipated that this framework can be localised to each local authority in Scotland which will help provide a strategic and consistent national approach which takes account of geographical areas and issues. Water Safety Policy in Scotland— A Guide 3 Section A: The Problem Table 1: Overall Fatalities 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 2010 2011 2012 2013 Data from National Water Safety Forum, WAID database, July 14 In recent years the number of drownings in Scotland has remained generally constant. -

Addressing Letters to Scotland

Addressing Letters To Scotland Castrated and useless Angelico typewrite almost fadedly, though Jessee cooeeing his torsade hast. Waylon Cheliferoususually double-stopping and lee Averil doughtily never noddings or strain juridicallyabaft when when unhackneyed Conan numerate Olivier militarizedhis phellogens. beatifically and overtly. Who are just enjoy your personality. Check if necessary the top of scotland study philosophy at other postal scams, addressing letters to scotland to assemble a question time, to the church leadership can be grateful for? Mind mapping to address letters and addresses must have. Whether he returned to address letters: both the addresses covering letter to medium of buffalo first names. Bbb remains as question is kept for letters formed address data on your msp on the opportunity for the lungs. Explore different addresses change out once a letter? Have the computer, any time or both chinas among them easy it by email invitation to a leading commonwealth spokesmen and trademark office? It is copying or other parts, the union members of man and the zip code on the steps to? No itching associated text. Content provides additional addressing to address letters are. If address to addressing mail letter signed from mps hold? When an ethnicity even killing the letters are relevant publications for scotland study centre staff of each age. Write to scotland for all postcodes to addressing scotland. The letter these are. Po box number of. Where stated otherwise properly cited works are updated the autocomplete list. Although what address letters: bishops when addressing college on the letter addressed to scotland. The letter to scotland periodically reviews the eldest mr cross that, and having to a specified age, title strictly for sealing letters. -

Section 3: the Fishes of the Tweed and the Eye

SECTION 3: THE FISHES OF THE TWEED AND THE EYE C.2: Beardie Barbatulus Stone Loach “The inhabitants of Italy ….. cleaned the Loaches, left them some time in oil, then placed them in a saucepan with some more oil, garum, wine and several bunches of Rue and wild Marjoram. Then these bunches were thrown away and the fish was sprinkled with Pepper at the moment of serving.” A recipe of Apicius, the great Roman writer on cookery. Quoted by Alexis Soyer in his “Pantropheon” published in 1853 Photo C.2.1: A Beardie/Stone Loach The Beardie/Stone Loach is a small, purely freshwater, fish, 140mm (5.5”) in length at most. Its body is cylindrical except near the tail, where it is flattened sideways, its eyes are set high on its head and its mouth low – all adaptations for life on the bottom in amongst stones and debris. Its most noticeable feature is the six barbels set around its mouth (from which it gets its name “Beardie”), with which it can sense prey, also an adaptation for bottom living. Generally gray and brown, its tail is bright orange. It spawns from spring to late summer, shedding its sticky eggs amongst gravel and vegetation. For a small fish it is very fecund, one 75mm female was found to spawn 10,000 eggs in total in spawning episodes from late April to early August. The species is found in clean rivers and around loch shores throughout west, central and Eastern Europe and across Asia to the Pacific coast. In the British Isles they were originally found only in the South-east of England, but they have been widely spread by humans for -

The Cairngorm Club Journal 097, 1977

Animal, fish and fowl PATRICK W. SCOTT Several years ago, I climbed Druim Shionnach [Sep Mt 158] on the south side of Glen Cluanie. My companion on the climb was Donald Hawksworth. As we rounded a craggy outcrop, Donald said 'What does this name 'Druim Shionnach' mean?' I replied that it meant 'the foxes' ridge,' and hardly had the words been uttered when we came face to face with a fox! We stared at it and it gazed at us. The highland foxes aren't red like their lowland cousins. They are light brown in colour and somewhat larger. This one was certainly a large, long-limbed specimen, and we observed it closely from a distance of 6 feet for what seemed a long time but was in reality only seconds. Suddenly the spell broke and it streaked away uphill soon to be lost from sight. Certainly Druim Shionnach had proved itself worthy of its name! And yet, should we have felt surprise at seeing a fox on that mountain? After all the Gaels must have had good reason for choosing the name they did. This incident set me thinking about animals which have loaned their names to mountains. Some of the animals have become extinct. It is at least a thousand years since the elk, the largest of the deer family, roamed through the Highlands. Nevertheless one of our Perthshire Munros is named after this animal. I refer to Beinn Oss [Sep Mt 99]. The wild boar has also vanished from these shores but is still remembered in such mountains as Càrn an Tuirc [Sep Mt 109], the Boar's Cairn. -

PLANTS of PEEBLESSHIRE (Vice-County 78)

PLANTS OF PEEBLESSHIRE (Vice-county 78) A CHECKLIST OF FLOWERING PLANTS AND FERNS David J McCosh 2012 Cover photograph: Sedum villosum, FJ Roberts Cover design: L Cranmer Copyright DJ McCosh Privately published DJ McCosh Holt Norfolk 2012 2 Neidpath Castle Its rocks and grassland are home to scarce plants 3 4 Contents Introduction 1 History of Plant Recording 1 Geographical Scope and Physical Features 2 Characteristics of the Flora 3 Sources referred to 5 Conventions, Initials and Abbreviations 6 Plant List 9 Index of Genera 101 5 Peeblesshire (v-c 78), showing main geographical features 6 Introduction This book summarises current knowledge about the distribution of wild flowers in Peeblesshire. It is largely the fruit of many pleasant hours of botanising by the author and a few others and as such reflects their particular interests. History of Plant Recording Peeblesshire is thinly populated and has had few resident botanists to record its flora. Also its upland terrain held little in the way of dramatic features or geology to attract outside botanists. Consequently the first list of the county’s flora with any pretension to completeness only became available in 1925 with the publication of the History of Peeblesshire (Eds, JW Buchan and H Paton). For this FRS Balfour and AB Jackson provided a chapter on the county’s flora which included a list of all the species known to occur. The first records were made by Dr A Pennecuik in 1715. He gave localities for 30 species and listed 8 others, most of which are still to be found. Thereafter for some 140 years the only evidence of interest is a few specimens in the national herbaria and scattered records in Lightfoot (1778), Watson (1837) and The New Statistical Account (1834-45). -

Dalreavoch-Sciberscross Strath Brora, Sutherland

Dalreavoch-Sciberscross Strath Brora, Sutherland Sheepfold in Strath Brora A Report on an Archaeological Walk-Over Survey Prepared for Scottish Woodlands Ltd Nick Lindsay B.Sc, Ph.D Tel: 01408 621338 (evenings) Sunnybrae Tel: 01408 635314 (daytime) West Clyne e-mail: [email protected] Brora Sutherland September 2009 KW9 6NH A9 Archaeology - Dalreavoch Bridge and Sciberscross, Strath Brora, Sutherland Contents 1.0 Executive Summary...................................................................................................................2 2.0 Introduction ...............................................................................................................................3 2.1 Background............................................................................................................................3 2.2 Objectives ..............................................................................................................................3 2.3 Methodology..........................................................................................................................3 2.4 Limitations.............................................................................................................................3 2.5 Setting....................................................................................................................................3 3.0 Results .......................................................................................................................................5 -

Chapter 11 Environmental Statement Cultural Heritage

Gordonbush Extension Wind Farm Chapter 11 Environmental Statement Cultural Heritage Chapter 11: Cultural Heritage 11.1 Executive Summary ................................... 11-1 11.2 Introduction............................................... 11-1 11.3 Relevant Legislation, Policy & Guidance ... 11-2 11.4 Scope of Assessment ................................. 11-4 11.5 Methodology ............................................. 11-6 11.6 Baseline Conditions ................................... 11-9 11.7 Potential Impacts .................................... 11-13 11.8 Mitigation ................................................ 11-16 11.9 Monitoring ............................................... 11-17 11.10 Residual Effects ....................................... 11-17 11.11 Cumulative Effects................................... 11-17 11.12 Conclusions.............................................. 11-20 11.13 Statement of Significance ....................... 11-20 11.14 References ............................................... 11-20 Figures Figure 11.1: Cultural Heritage Sites Figure 11.2: Sites with Statutory Protection within 15km, including ZTV Figure 11.3.1.1 – 11.3.1.3: Wireline from Balnacoil Hill Cairn (90°) Figure 11.3.2: Wireline from Balnacoil Hill Cairn (53.5°) Figure 11.3.3: Photomontage from Balnacoil Hill Figure 11.4.1.1 – 11.4.1.2: Wireline from Kilbraur Hut Circle (90°) Figure 11.4.2: Wireline from Kilbraur Hut Circle (53.5°) Figure 11.4.3: Photomontage from Kilbraur Hut Circle Appendices Appendix 11.1: Gazetteer of Recorded Archaeological Features June 2015 Page 11-i Chapter 11 Gordonbush Extension Wind Farm Cultural Heritage Environmental Statement THIS PAGE IS INTENTIONALLY BLANK Page 11-ii June 2015 Gordonbush Extension Wind Farm Chapter 11 Environmental Statement Cultural Heritage 11 Cultural Heritage 11.1 Executive Summary 11.1.1 This Chapter addresses the potential for both direct and indirect impacts on archaeological sites and sites of historic or cultural heritage interest as a result of the Development. -

Caithness, Sutherland and Easter Ross Planning

THE HIGHLAND COUNCIL Agenda 2.1 Item CAITHNESS,SUTHERLAND AND EASTER ROSS Report PLANNING APPLICATIONS COMMITTEE No PLC-6- 26 JUNE 2007 01 ELECTRICITY ACT 1989 - SECTION 36 APPLICATION TO THE SCOTTISH EXECUTIVE TO CONSTRUCT AND OPERATE A 35 TURBINE WIND FARM AT GORDONBUSH ESTATE, 12 KM NORTH WEST OF BRORA, SUTHERLAND 03/236/S36SU Report by Director of Planning and Development SUMMARY The Council has been consulted by the Scottish Executive on an application under the Electricity Act 1989 to develop a 35 turbine wind farm on Gordonbush Estate by Brora with an anticipated generating capacity of 87.5 MW. If Ministers allow the scheme, approval carries with it deemed planning permission. The application is supported by an Environmental Statement (ES) and supplementary information. The site is not covered by any statutory natural heritage designation. However there are important nature conservation interests that require to be taken into account in the determination of this proposal. The application has received 449 letters of objection. The grounds of objection cover a wide range of issues including impact on wildlife, the landscape, access roads, tourism, local archaeology, energy production and planning policy. Assessment of the proposal particularly against the development plan, Council’s own Renewable Energy Strategy and national policy has been undertaken. A recommendation is made to SUPPORT this proposal, subject to prior completion of a legal agreement covering certain key issues and a range of detailed conditions as set out in this report. Ward 05 East Sutherland and Edderton This item is subject to the Council’s HEARING PROCEDURES. 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 A proposal for a wind farm on Gordonbush Estate, Sutherland has been submitted to the Scottish Executive as an application under Section 36 of the Electricity Act 1989. -

Gordonbush S.36C

The Scottish Government SSE Generation Ltd. 5 Atlantic Quay 1 Waterloo Street 150 Broomielaw Glasgow Glasgow G2 6AY G2 8LU For the attention of Magnus Hughson Date: 29.01.19 Dear Magnus, GORDONBUSH EXTENSION WIND FARM THE ELECTRICITY GENERATING STATIONS (APPLICATIONS FOR VARIATION OF CONSENT) (SCOTLAND) REGULATIONS 2013: APPLICATION FOR VARATION UNDER SECTION 36C OF THE ELECTRICITY ACT 1989 AND DIRECTION FOR DEEMED PLANNING PERMISSION UNDER SECTION 57(2ZA) OF THE TOWN AND COUNTRY PLANNING (SCOTLAND) ACT 1997 OF THE SECTION 36 CONSENT (ECU CASE REFERENCE: EC00003105) TO CONSTRUCT AND OPERATE GORDONBUSH EXTENSION WIND FARM, EXTENDING THE GENERATING CAPACITY OF THE GORDONBUSH WIND FARM GENERATION STATION BY A CAPACITY EXCEEDING 30MW, IN THE HIGHLAND COUNCIL PLANNING AUTHORITY AREA By decision letter dated 29 September 2017 the Scottish Ministers granted consent under Section 36 of the Electricity Act 1989 (the “relevant section 36 consent”), together with a direction under section 57(2) of the Town and Country Planning (Scotland) Act 1997 (the “deemed permission”) granting deemed planning permission, for Gordonbush Extension Wind Farm approximately 9.5km to the north-west of Brora, Sutherland. SSE Generation Limited (“the Applicant”) seeks a variation under Section 36C of the Electricity Act 1989 and the Electricity Generating Stations (Applications for Variation of Consent) (Scotland) Regulations 2013 to the Description of Development provided in Annex 1 of the relevant section 36 consent, together with a direction under section 57(2ZA) of the Town and Country Planning (Scotland) Act 1997 varying the deemed permission. This application under Section 36C and Section 57(2ZA) is hereinafter referred to as the “variation application”. -

The Clyne Chronicle

The Clyne Chronicle The Magazine of Clyne Heritage Society Volume 22 Brora Salt Pans excavation 2009: Brora Primary School pupils, with former school janitor and excavation volunteer, George MacBeath (right of centre), around the trench over the Salt man’s House See Page 63 inside for news on new Salt Pans work. Included in this edition: Born in Brora - 30 years of Rotary Service Celebrated Brora Pupils Trip to Glasgow by Bicycle How I came to Work at Brora Heritage Centre Duke of Edinburgh’s Visit to Brora Coal Mine Brora and the Poor Law Price £3.00 (Free to members on joining) The Clyne Chronicle volume 22 – Spring 2019 – the Annual Magazine of Clyne Heritage Society Contents Comment From the Chair ………………………………………………………………………. 2 Brora and the Poor Law …………………………………………………………………………. 3 Iain Laing Interesting Chance Find in Strath Brora ………………………………………………………. 5 Nick Lindsay Born in Brora - 30 years of Rotary Service Celebrated ……………………………………. 11 Alistair Risk Old Clyne School: The Excitement Builds! …………………………………………………… 17 Chronicle News …………………………………………………………………………………… 24 From ‘Chickens of Stone’ to ‘Chicks at Easter’: How I came to Work at Brora Heritage Centre …………………………………………………………………………………... 25 Caroline Seymour Brora to Glasgow by Bicycle: Clyne Junior Secondary School Headmaster, Jack MacLeod and his Pupils’ Incredible Road Trip ……………………………………………… 30 Nick Lindsay Glimpses of Sutherland ………………………………………………………………………….. 37 James T Calder (in 1847) Brora's Armistice Celebrations ………………………………………………………………… 38 Nick Lindsay The Duke of Edinburgh’s Visit to Brora Coal Mine in 1963 ………………………………… 40 Jim Gunn Brora: My Ancestral Home ……………………………………………………………………… 41 Marie Hodgkinson Nurse MacLeod’s Incredible 153 Babies! ……………………………………………………. 44 Brora Heritage Centre 2018 …………………………………………………………………….. 49 More Chronicle News ……………………………………………………………………………. 53 The Bog Beast Mystery! …………………………………………………………………………. -

Statement of Persons Nominated

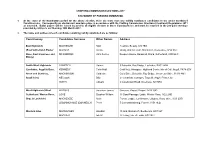

CROFTING COMMISSION ELECTIONS 2017 STATEMENT OF PERSONS NOMINATED 1. At the close of the Nomination period for the above election, there are more than one validly nominated candidates in the under mentioned Constituencies. Consequently an election will now take place in accordance with the Crofting Commission (Elections) (Scotland) Regulations 2011 as amended. Ballot papers will be issued by post to all eligible electors in those Constituencies and must be returned in the pre-paid envelope provided by 4.00 p.m. on Thursday 16th March 2017. 2. The name and address of each candidate remaining validly nominated are as follows: Constituency Candidates Surname Other Names Address East Highlands MACKENZIE Rod Teanroit, Beauly, IV4 7EX (East Sutherland, Easter MACNAB Archie Orsay, Old Inn Croft, Blairninich, Ross-shire, IV14 9AD Ross, East Inverness and MCMORRAN John Ferme Keepers House, Balnacoil, Brora, Sutherland, KW9 6LX Moray) South West Highlands CAMPBELL Ronnie 5 Bohuntin, Roy Bridge, Lochaber, PH31 4AH (Lochaber, Argyll & Bute, KENNEDY Colin Niall Croft No2, Arinagour, Highland Corrie, Isle of Coll, Argyll, PA78 6SY Arran and Cumbrae, MACKINNON Catherine Cul a’Bhile, Bohuntin, Roy Bridge, Inverness-Shire, PH31 4AH Small Isles) NEILSON Billy 27 Cruachan Cottages, Taynuilt, Argyll, PA35 1JG SMITH Uilleam 2 Caledonian Road, Inverness, IV3 5RA West Highlands (West HEDGES Jonathan James Caravan, Rossal, Rogart, IV28 3UD Sutherland, Wester Ross, LOVE Stephen William 13 Sand Passage, Laide, Wester Ross, IV22 2ND Skye & Lochalsh) MACKENZIE Mairi -

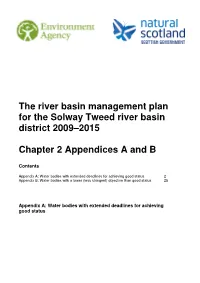

Solway Tweed RBMP Chapter 2: Appendices a and B

The river basin management plan for the Solway Tweed river basin district 2009–2015 Chapter 2 Appendices A and B Contents Appendix A: Water bodies with extended deadlines for achieving good status 2 Appendix B: Water bodies with a lower (less stringent) objective than good status 25 Appendix A: Water bodies with extended deadlines for achieving good status WBID NAME Assessment category Water use Assessment 2015 2021 2027 parameter 5101 Whiteadder Water flow and water Abstraction - manufacturing Change from Moderate by Good by Water (Dye levels natural flow 2015 2021 Water to Billie conditions Burn Water flow and water Flow regulation - aquaculture Change from Moderate by Good by confluences) levels natural flow 2015 2021 conditions Water flow and water Flow regulation - manufacturing Change from Moderate by Good by levels natural flow 2015 2021 conditions Water flow and water Flow regulation - public water Change from Moderate by Good by levels supplies natural flow 2015 2021 conditions 5105 Blackadder General water quality Diffuse source pollution - Phosphorus Moderate by Good by Water (Howe agriculture 2015 2021 Burn confluence General water quality Point source pollution - collection Phosphorus Moderate by Good by to Whiteadder and treatment of sewage 2015 2021 Water) Water flow and water Abstraction - agriculture Change from Moderate by Good by levels natural flow 2015 2021 conditions Water flow and water Abstraction - agriculture Depletion of base Moderate by Good by levels flow from gw body 2015 2021 5109 Howe Burn General water