The Metaphysical Review 28/29

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SFRA Newsletter 259/260

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications 12-1-2002 SFRA ewN sletter 259/260 Science Fiction Research Association Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scifistud_pub Part of the Fiction Commons Scholar Commons Citation Science Fiction Research Association, "SFRA eN wsletter 259/260 " (2002). Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications. Paper 76. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scifistud_pub/76 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. #2Sfl60 SepUlec.JOOJ Coeditors: Chrlis.line "alins Shelley Rodrliao Nonfiction Reviews: Ed "eNnliah. fiction Reviews: PhliUp Snyder I .....HIS ISSUE: The SFRAReview (ISSN 1068- 395X) is published six times a year Notes from the Editors by the Science Fiction Research Christine Mains 2 Association (SFRA) and distributed to SFRA members. Individual issues are not for sale. For information about SFRA Business the SFRA and its benefits, see the New Officers 2 description at the back of this issue. President's Message 2 For a membership application, con tact SFRA Treasurer Dave Mead or Business Meeting 4 get one from the SFRA website: Secretary's Report 1 <www.sfraorg>. 2002 Award Speeches 8 SUBMISSIONS The SFRAReview editors encourage Inverviews submissions, including essays, review John Gregory Betancourt 21 essays that cover several related texts, Michael Stanton 24 and interviews. Please send submis 30 sions or queries to both coeditors. -

The Banksoniain #8 an Iain (M.) Banks Fanzine November 2005

The Banksoniain #8 An Iain (M.) Banks Fanzine November 2005 Editorial Banks’s Next Books Issue #8 marks somewhat of a departure from Details of the 2006 vintage Banks have begun the normal Banksoniain with a new (for us) to become available, with listings starting to writer, Martyn Colebrook, taking up the appear on Amazon and the like as Little, challenge of the book biography centre Brown, the publisher, makes pre-publication spread. information available about the work Untitled The diversity that makes up the Strange Iain Banks. Worlds of Iain (M) Banks is I believe pretty The various ISBNs that are floating about are: much illustrated by the contents of this issue. 0316731056 for the hardback; 0316731064 As well as the book biography focus on Canal for the trade paperback (the one you will find Dreams, we have news of his forthcoming in airport bookshops) and 1405501251 for the books, his Culture novels being a specialist CD audio-book abridgement. These all have subject on the TV quiz show, Mastermind, an the same prospective release date being academic conference being planned about his September 1st 2006, and somehow Amazon work, and more. manage, whilst Iain is still writing the book, There is a fair bit of Banks related Worldcon to claim that it will be 416 pages long. These news to catch up on and we also have a pieces of information should probably be personal view from Iain Banks Forum regular taken in descending order of credibility. Coercri as well as a few thoughts from your The further books of his current three book editor. -

The Banksoniain 17

The Banksoniain #17 An Iain (M.) Banks Fanzine April 2012 Editorial Banks’s Next Book The publication of Stonemouth is upon us. Iain is writing, or hopefully just about Apologies for not publishing in 2011, but then finishing, an ‘M’ book at the moment. An again neither did Iain. This issue looks at the early public comment about it was in an build up to the new book, and also the next interview with Irish SF magazine Albedo Culture novel, The Hydrogen Sonata. There is One (issue 41) that was conducted in April a bit more film news, and over a year of 2011. At that point he said it was to be Banks’s public appearances to report on, as “written over Jan/Feb/Mar next year, and it’s well as the calendar of forthcoming Banks almost certain to be a Culture novel.” He events on the back page. added that, “I think I need to tackle the idea of Subliming; it has delighted us with its The Wasp Factory Film vagueness long enough.” This is a long and complicated story Early in January 2012 it got an ISBN, previously discussed in various editions of 9780356501505, and a listing on book selling The Banksoniain. There was a step forward websites calling it Untitled New Iain M. when on the Friday of Novacon 40 Banks 1. However, Iain said that the working (12/11/2010) Iain commented that a deal had title was, The Hydrogen Sonata, and this was been done, and on the night he mentioned confirmed when bookselling websites were Stephen Daldry. -

See Page 19 for Details!!

RRegionegion 1177 SSummit/Marineummit/Marine MMusteruster MMayay 220-220-22 128 DDenver,enver, CColoradoolorado APR 2005/ MAY 2005 SSeeee ppageage 1199 fforor ddetails!!etails!! USS Ark Angel’s CoC and Marines’ Fall Muster ’04 see pages 19 & 20 for full story! “Save Star Trek” Rally see page 28 for more great pics! Angeles member Jon Lane with the “Enterprise” writing staff. From left to right: Jon Lane, “Enterprise” writers Judith and Garfi eld Reese-Stevens, and producer Mike Sussman. Many of the the show’s production staff wandered out to see the protest and greet the fans. USPS 017-671 112828 112828 STARFLEET Communiqué Contents Volume I, No. 128 Published by: FROM THE EDITOR 2 STARFLEET, The International FRONT AND CENTER 3 Star Trek Fan Association, Inc. EC/AB SUMMARY 3 102 Washington Drive VICARIOUS CHOC. SALUTATIONS 4 Ladson, SC 29456 COMM STATIC 4 Kneeling: J.R. Fisher THE TOWAWAY ZONE 5 (left to right) 1st Row: Steve Williams, Allison Silsbee, Lauren Williams, Alastair Browne, The SHUTTLEBAY 6 Amy Dejongh, Spring Brooks, Margaret Hale. 2nd Row: John (boyfriend of Allison), Katy Publisher: Bob Fillmore COMPOPS 6 McDonald, Nathan Wood, Larry Pischke, Elaine Pischke, Brad McDonald, Dawn Silsbee. Editor in Chief: Wendy Fillmore STARFLEET Flag Promotions 7 Layout Editor: Wendy Fillmore Fellowship...or Else! 7 3rd Row: Colleen Williams, Jonathan Williams. Graphics Editor: Johnathan Simmons COMMANDANTS CORNER 8 Submissions Coordinator: Wendy Fillmore SFI Academy Graduates 8 Copy Editors: Gene Adams, Gabriel Beecham, New Chairman Sought for ASDB! 9 Kimberly Donohoe, Michael Klufas, Tracy Lilly, Star Trek Encyclopedia Project 9 STARFLEET Finances 10 Bruce Sherrick EDITORIALS 11 Why I Stopped Watching.. -

SF COMMENTARY 81 40Th Anniversary Edition, Part 2

SF COMMENTARY 81 40th Anniversary Edition, Part 2 June 2011 IN THIS ISSUE: THE COLIN STEELE SPECIAL COLIN STEELE REVIEWS THE FIELD OTHER CONTRIBUTORS: DITMAR (DICK JENSSEN) THE EDITOR PAUL ANDERSON LENNY BAILES DOUG BARBOUR WM BREIDING DAMIEN BRODERICK NED BROOKS HARRY BUERKETT STEPHEN CAMPBELL CY CHAUVIN BRAD FOSTER LEIGH EDMONDS TERRY GREEN JEFF HAMILL STEVE JEFFERY JERRY KAUFMAN PETER KERANS DAVID LAKE PATRICK MCGUIRE MURRAY MOORE JOSEPH NICHOLAS LLOYD PENNEY YVONNE ROUSSEAU GUY SALVIDGE STEVE SNEYD SUE THOMASON GEORGE ZEBROWSKI and many others SF COMMENTARY 81 40th Anniversary Edition, Part 2 CONTENTS 3 THIS ISSUE’S COVER 66 PINLIGHTERS Binary exploration Ditmar (Dick Jenssen) Stephen Campbell Damien Broderick 5 EDITORIAL Leigh Edmonds I must be talking to my friends Patrick McGuire The Editor Peter Kerans Jerry Kaufman 7 THE COLIN STEELE EDITION Jeff Hamill Harry Buerkett Yvonne Rousseau 7 IN HONOUR OF SIR TERRY Steve Jeffery PRATCHETT Steve Sneyd Lloyd Penney 7 Terry Pratchett: A (disc) world of Cy Chauvin collecting Lenny Bailes Colin Steele Guy Salvidge Terry Green 12 Sir Terry at the Sydney Opera House, Brad Foster 2011 Sue Thomason Colin Steele Paul Anderson Wm Breiding 13 Colin Steele reviews some recent Doug Barbour Pratchett publications George Zebrowski Joseph Nicholas David Lake 16 THE FIELD Ned Brooks Colin Steele Murray Moore Includes: 16 Reference and non-fiction 81 Terry Green reviews A Scanner Darkly 21 Science fiction 40 Horror, dark fantasy, and gothic 51 Fantasy 60 Ghost stories 63 Alternative history 2 SF COMMENTARY No. 81, June 2011, 88 pages, is edited and published by Bruce Gillespie, 5 Howard Street, Greensborough VIC 3088, Australia. -

NASFA 'Shuttle' Jun 2005

The SHUTTLE June 2005 The Next NASFA Meeting Will Be 18 June 2005 at the Regular Time and Location The Next Con Stellation ConCom Meeting Will Be 7 July 2005 at Marie McCormackÕs House { Oyez, Oyez { NASFA Calendar The next NASFA meeting will be 18 June 2005 at the JUNE regular time and location. 01 BD: Glenn Valentine. The June program is TBD at press time. The June after- 02 Concom Meeting: Marie McCormackÕs house. the-meeting meeting will be at Mike KennedyÕs house; 7907 02 BD: Lloyd Penney. Charlotte Drive SW, Huntsville. 03Ð05 ConCarolinas Ñ Charlotte NC. Due to space (and time!) limitations, the ongoing adven- 10Ð12 Sci-Fi Summer Con 2005 Ñ Atlanta GA. tures of PieEyedDragon will not appear in this issue. It is 14 Flag Day. scheduled to resume next month. (continued on page 2) Inside this issueÉ Minutes of the May Meeting ..........................................2 Time Magazine Top 100 Movie List ..............................5 Review of The Star Wars Saga .......................................3 Awards Roundup ............................................................5 NASFA Receivables .......................................................4 Letters of Comment ........................................................8 Deadline for the July 2005 issue of The NASFA Shuttle is Friday, 1 July 2005. th Our 25 Year of1 Publication! 17Ð19 HyperiCon Ñ Nashville TN. Committee meeting (if scheduled) is at 5P. The business 18* NASFA Meeting Ñ 6P Business, 7P Program, at meeting is at 6P. The program is at 7P. Anyone is welcome to BookMark. Program: TBD. ATMM: Mike Ken- attend any of the meetings. There is usually an after-the- nedyÕs house. meeting meeting with directions available at the program. 19 FathersÕ Day. 21 First Day of Summer. -

Rejecting Limits and Opening Possibilities in the Works of Iain Banks

Rejecting Limits and Opening Possibilities in the Works of Iain Banks Olga Roebuck Abstract This text deals with the question of Scottish self-definition and also the escape from it. Scottish identity debate in 1980s and 1990s took on different forms and searched for other inspirations: outside Scotland or in dealing with identities traditionally overlooked due to the overall focus on national identity. This paper thus analyses the question of Scottishness through the subversive voice addressing the identities traditionally problematic in Scotland or even through individual self-definition as presented in Iain Banks’s novels The Wasp Factory (1984) and The Crow Road (1992). Keywords Scotland, cultural subversion, Scottishness, Iain Banks, The Wasp Factory, The Crow Road The classification of Iain Banks as a writer is probably as difficult as the classification of Scottishness itself. To claim that Iain Banks is a representative of a Scottish literary tradition poses several problems: to what extent can the works of this author be regarded as representative and how does he fit into the context of any literary tradition? He is not part of any school or movement and his literary voice does not fall under any simple label. Banks embodies many dualities, many undecided and hard-to-classify issues – and this is perhaps a feature that makes him particularly Scottish. To assess the cultural milieu as represented in Banks’s works, the most significant aspect seems to be an omnipresent mood of identity tiredness. After the traumatic experience of the failed devolution vote in 1979, when Scotland lost the chance to alter its status as a stateless nation after not being able to muster the necessary forty per cent of votes to enable the abolishing of the Home Rule, the sense of national identity sank into depths. -

The Banksoniain #10 an Iain (M.) Banks Fanzine August 2006

The Banksoniain #10 An Iain (M.) Banks Fanzine August 2006 Editorial Banks’s Next Books Apologies for the lateness of this issue, The next Banks book has been put back to unfortunately real life got in the way of March 2007. It also seems to have undergone writing and it basically missed its slot in my a name change and is now called The Steep quarterly schedule. If you want issues to Approach to Garbadale, rather than Matter come out on a more regular basis then please (which could have been a dull Physics contribute articles, or even just ideas for textbook). It also seems to have had another articles, or anything really. Contact details at working title, Empire (a History textbook?) the end of the last page. Please expect publication to be biannual from now on so The book after next, an Iain M. Banks effort look for issue #11 in February 2007. that is definitely Culture - the opening section of this book having been written before Steep The issue features The Crow Road, the book, Approach was started - has also been put back the TV series, the radio reading and the audio as a consequence of its predecessor‟s delay. book, and to help you make all the Iain is taking the summer off, and probably connections we have produced a family tree the winter as well, and plans to start work on of the major characters. This is probably my the Untitled Culture Novel in 2007 with favourite Banks book, and I found it difficult publication currently scheduled for August to write about possibly for that reason, but 2008. -

Scratch Pad 20

Scratch Pad 20 Based on the non-Mailing Comments section of The Great Cosmic Donut of Life No. 9, a magazine written and published by Bruce Gillespie, 59 Keele Street, Victoria 3066, Australia (phone (03) 9419-4797; email: [email protected]) for the December 1996 mailing of Acnestis. Contents 1 A TASTE FOR MAYHEM: PRELIMINARY NOTES 3 BOOKS READ SINCE AUGUST 1996 by Bruce ON iAIN BANKS’S NON-SF NOVELS by Bruce Gillespie Gillespie A TASTE FOR MAYHEM: Preliminary notes on IAIN BANKS’S NON-SF NOVELS Presented as a talk to the Nova Mob, Melbourne’s SF discussion group, 6 November 1996. At the same meeting, Race Mathews gave a talk about Iain Bank’s SF novels, which I’ll reprint as soon as possible. The legend sitting room was only about six or seven feet away so I Banks, Iain with or without a middle ‘M.’, is the stuff of handed my drink to one of the people (I think they were legend. from Andromeda Bookshop in Birmingham) cause I’d The legend runs that he had published three novels spotted a loophole, you see, because I wasn’t actually before someone told him he was an SF writer and climbing. This was about the third or fourth storey, and dragged him along to a convention. The legend adds it was actually a traverse; I wasn’t actually gaining any that he decided to join the SF community and write real height. So I did this, but unfortunately at the same time SF books when he discovered the capacity of the British as this there was a burglar taking things next door and fan for putting away booze at conventions. -

America and the World in the Age of Obama

America and the World in the Age of Obama Columns and articles by Ambassador Derek Shearer Table of Contents Preface Hillary As An Agent of Change 1 Change That Really Matters 5 Sex, Race and Presidential Politics 8 Why Bipartisanship is a False Hope 11 Balance of Payments: Homeland Insecurity 14 Economics and Presidential Politics—“It’s Globalization, Stupid” 16 Beyond Gotcha: In Search of Democratic Economics 18 Rebranding America: How to Win Friends Abroad and Influence Nations 21 Waiting for Obama: The First Global Election 23 The Proper Use of Bill and Hillary Clinton 26 Clintonism Without Clinton—It’s Deja Vu All Over Again 28 Russia and the West Under Clinton and Bush 30 What’s At Stake: The Future vs The Past 34 The Road Ahead: The First 100 Days and Beyond 37 The Shout Heard Round the World: Obama as Global Leader 41 An Obama Holiday: What to Give a Progressive President and His Team 47 Bye, Bye Bush, Hello Barack: A Door Opens in 2009 52 Hoops Rule: The President and the Hard Court 55 After the Stimulus: It’s Time for a New Foundation 57 Advice to the President: Abolish the Commerce Department 62 Money, Banking and Torture: It’s Just Shocking! 65 Give Hope A Chance: The Renewal of Summer 68 Obama’s America: What is Economic Growth For? 71 Obama’s First Year: A Nobel Effort 75 Joy to the World: Good-Bye Bing Crosby, Hello Bob Dylan 78 Passage to India: Monsoon Wedding Meets Slumdog Professor 84 The Occidental President: Obama and Teachable Moments 88 Happy Days Are Not Here Again: Obama, China and the Coming Great Contraction -

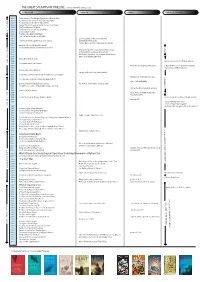

Download the Timeline and Follow Along

THE GREAT STEAMPUNK TIMELINE (to be printed A3 portrait size) LITERATURE FILM & TV GAMES PARALLEL TRACKS 1818 - Frankenstein: or The Modern Prometheus (Mary Shelley) 1864 - A Journey to the Centre of the Earth (Jules Verne) K N 1865 - From the Earth to the Moon (Jules Verne) U P 1869 - Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea (Jules Verne) - O 1895 - The Time Machine (HG Wells) T O 1896 - The Island of Doctor Moreau (HG Wells) R P 1897 - Dracula (Bram Stoker) 1898 - The War of the Worlds (HG Wells) 1901 - The First Men in the Moon (HG Wells) 1954 - 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Disney) 1965 - The Wolves of Willoughby Chase (Joan Aiken) The Wild Wild West (CBS) 1969 - Captain Nemo and the Underwater City (MGM) 1971 - Warlord of the Air (Michael Moorcock) 1973 - A Transatlantic Tunnel, Hurrah! (Harry Harrison) K E N G 1975 - The Land That Time Forgot (Amicus Productions) U A 1976 - At the Earth's Core (Amicus Productions) P S S 1977 - The People That Time Forgot (Amicus Productions) A R 1978 - Warlords of Atlantis (EMI Films) B Y 1979 - Morlock Night (K. W. Jeter) L R 1982 - Burning Chrome, Omni (William Gibson) A E 1983 - The Anubis Gates (Tim Powers) 1983 - Warhammer Fantasy tabletop game > Bruce Bethke coins 'Cyberpunk' (Amazing) 1984 - Neuromancer (William Gibson) 1986 - Homunculus (James Blaylock) 1986 - Laputa Castle in the Sky (Studio Ghibli) 1987 - > K. W. Jeter coins term 'steampunk' in a letter to Locus magazine -

New Items @ Your Library August

What’s New New items @ your library August New Items @ Your Library Biography B 920.5 MUR The Murdoch method : notes on running a media empire Irwin Stelzer. B 920.5 PAT The art of not falling apart Christina Patterson. B 920.72 FEE Places I stopped on the way home : a memoir of chaos and grace Meg Fee. B 920.9155 SPE The dead moms club Kate Spencer. B 920.9362 HAR Too scared to cry Maggie Hartley. B 920.9362 HAR Who will love me now? Maggie Hartley. B 920.9362 HAR Tiny prisoners Maggie Hartley. B 920.9616 MER This close to happy : a reckoning with depression Daphne Merkin. B 923.01 HAL Familiar stranger : a life between two islands Stuart Hall with Bill Schwarz. B 923.2 EVA Incorrigible optimist : a political memoir Gareth Evans. B 923.2 LIN Six encounters with Lincoln Elizabeth Brown Pryor. B 923.2 MEG American princess : the love story of Meghan Markle and Prince Harry Leslie Carroll. B 923.2 MEG Meghan : a Hollywood princess Andrew Morton. B 923.2712 SHU The spy who changed history Svetlana Lokhova. B 923.6 KHA When they call you a terrorist : a Black Lives Matter memoir Patrisse Khan-Cullors B 926.1 PAR The enlightened Mr. Parkinson Cherry Lewis. B 926.16833 Perseverance Tim Hague. HAG B 926.367 RYA Will's red coat : the story of one old dog who chose to live again Tom Ryan. B 926.367 SUT Rescuing Penny Jane Amy Sutherland. B 926.368 BOD Bodacious the shepherd cat : a charming tale of an extraordinary cat Suzanna Crampton.