DOWNLOAD Syed Hussein Alatas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Cabinet Will Lead BN Into

Headline New cabinet will lead BN into GEM MediaTitle New Straits Times Date 28 Jun 2016 Language English Circulation 74,711 Readership 240,000 Section Local News Color Full Color Page No 3 ArticleSize 267 cm² AdValue RM 9,168 PR Value RM 27,504 New cabinet will lead BN into GEM STRATEGIC: Appointments will strengthen coalition ahead of polls, say analysts election. responsibility. "It is a known fact that Noh had "Another Sabahan leader, Datuk made significant contributions to Datu Nasrun Datu Mansur, has also BN's win there. been appointed as a deputy min "I foresee that Noh will have free ister. It is a significant gain for rein over the design and execution Sabah." of BN's battle plan in Selangor." University of Tasmania's Asia In Khoo said the appointment of stitute director Professor Dr James Gerakan president Datuk Seri Mah Chin said Najib's decision not to axe THE unveiling of the new cab Siew Keong as plantation industries any minister from the cabinet meant inet lineup marks an impor and commodities minister was a big that the prime minister was con tant first step by Prime Min win for the multiracial party. fident in his team's strength. ister Datuk Seri Najib Razak in "Mah is now in charge of a min "I am surprised nobody was charting Barisan Nasional's course istry that is traditionally held by a dropped (from cabinet). towards the 14th General Election. Gerakan leader. It's a big morale "It means he has a solid cabinet While many have regarded the booster for the party," he said, that supports him 100 per cent. -

Passing the Mantle: a New Leadership for Malaysia NO

ASIA PROGRAM SPECIAL REPORT NO. 116 SEPTEMBER 2003 INSIDE Passing the Mantle: BRIDGET WELSH Malaysia's Transition: A New Leadership for Malaysia Elite Contestation, Political Dilemmas and Incremental Change page 4 ABSTRACT: As Prime Minister Mohamad Mahathir prepares to step down after more than two decades in power, Malaysians are both anxious and hopeful. Bridget Welsh maintains that KARIM RASLAN the political succession has ushered in an era of shifting factions and political uncertainty,as indi- New Leadership, Heavy viduals vie for position in the post-Mahathir environment. Karim Raslan discusses the strengths Expectations and weaknesses of Mahathir’s hand-picked successor,Abdullah Ahmad Badawi. He maintains that Abdullah will do well at moderating the influence of Malaysia’s more radical Islamic leaders, but page 9 doubts whether the new prime minister can live up to the excessive expectations that the polit- ical transition has engendered. M. Bakri Musa expresses hope that Abdullah will succeed where M. BAKRI MUSA (in his view) Mahathir has failed. For example, he urges the new leadership to revise Malaysia’s Post-Mahathir three-decade affirmative action policy and to tackle the problem of corruption. Malaysia: Coasting Along page 13 Introduction All three experts in this Special Report emphasize continuity.All agree that basic gov- Amy McCreedy ernmental policies will not change much; for fter more than 22 years in power, example, Abdullah Badawi’s seemingly heartfelt Malaysia’s prime minister Mohamad pledges to address corruption will probably A Mahathir is stepping down. “I was founder in implementation.The contributors to taught by my mother that when I am in the this Report do predict that Abdullah will midst of enjoying my meal, I should stop eat- improve upon Mahathir in one area: moderat- ing,”he quipped, after his closing remarks to the ing the potentially destabilizing force of reli- UMNO party annual general assembly in June. -

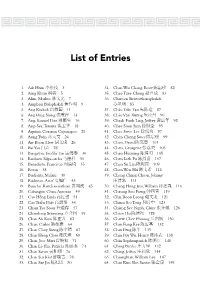

List of Entries

List of Entries 1. Aik Htun 3 34. Chan Wai Chang, Rose 82 2. Aing Khun 5 35. Chao Tzee Cheng 83 3. Alim, Markus 7 36. Charoen Siriwatthanaphakdi 4. Amphon Bulaphakdi 9 85 5. Ang Kiukok 11 37. Châu Traàn Taïo 87 6. Ang Peng Siong 14 38. Châu Vaên Xöông 90 7. Ang, Samuel Dee 16 39. Cheah Fook Ling, Jeffrey 92 8. Ang-See, Teresita 18 40. Chee Soon Juan 95 9. Aquino, Corazon Cojuangco 21 41. Chee Swee Lee 97 10. Aung Twin 24 42. Chen Chong Swee 99 11. Aw Boon Haw 26 43. Chen, David 101 12. Bai Yao 28 44. Chen, Georgette 103 13. Bangayan, Teofilo Tan 30 45. Chen Huiming 105 14. Banharn Silpa-archa 33 46. Chen Lieh Fu 107 15. Benedicto, Francisco 35 47. Chen Su Lan 109 16. Botan 38 48. Chen Wen Hsi 111 17. Budianta, Melani 40 49. Cheng Ching Chuan, Johnny 18. Budiman, Arief 43 113 19. Bunchu Rotchanasathian 45 50. Cheng Heng Jem, William 116 20. Cabangon Chua, Antonio 49 51. Cheong Soo Pieng 119 21. Cao Hoàng Laõnh 51 52. Chia Boon Leong 121 22. Cao Trieàu Phát 54 53. Chiam See Tong 123 23. Cham Tao Soon 57 54. Chiang See Ngoh, Claire 126 24. Chamlong Srimuang 59 55. Chien Ho 128 25. Chan Ah Kow 62 56. Chiew Chee Phoong 130 26. Chan, Carlos 64 57. Chin Fung Kee 132 27. Chan Choy Siong 67 58. Chin Peng 135 28. Chan Heng Chee 69 59. Chin Poy Wu, Henry 138 29. Chan, Jose Mari 71 60. -

Ungku Aziz's Perspective on 'Development'

Türkiye İslam İktisadı Dergisi, Cilt 2, Sayı 1, Şubat 2015, ss. 1-15 Turkish Journal of Islamic Economics, Vol. 2, No. 1, February 2015, pp. 1-15 UNGKU AZIZ’S PERSPECTIVE ON ‘DEVELOPMENT’ M. Syafiq BORHANNUDDIN1 Abstract This paper explores some key insights and lessons from Royal Professor Ungku Abdul Aziz bin Ungku Abdul Hamid (born 1922 – present), a celebrated academician in Malaysia, on development. Drawing from Ungku Aziz’s main articles, papers and books, the paper attempts to make wider connections with regards to Ungku Aziz’s endeavour in development. This paper sheds new light and draw lessons on the meaning of ‘development’ and its implications to the Muslim community. The main finding indicated that Ungku Aziz had creatively interpreted ‘development’ geared towards the needs of the local community away from the Western-centric notion and ideals. It is not mere imitation of modern Western conception of ‘development’, nor is it a wholesale rejection of it, but it is a creative interpretation that takes into consideration the economic reality as well as the spiritual, social and cultural well being of the local community. This study also revealed that the Ungku Aziz’s conception of ‘development’ has significant relationship with the right theological and civilizational interpretation of the religion of Islam. This paper contends that Ungku Aziz’s conception of ‘development’ should be expanded further using the right religious and civilizational framework as part of the continuous civilizing process of the Muslim world. Keywords: Ungku Aziz, Economic Thought, Development, Education, Well-Being, Malaysia 1.Introduction The 20th century saw the imposition of key concepts from a dominant civilization—the West—to the rest of the world. -

Fourth Malaysia Plan (Fmp)

THE FOURTH MALAYSIA PLAN (FMP) (RANCANGAN MALAYSIA KE-4, RME) 1981-1985 Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS.............................................................................................................................. 2 CHAPTER 01 : POLICY OBJECTIVES AND FRAMEWORK........................................................................... 6 I : INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................... 6 II : BACKGROUND TO THE NEP .................................................................................................. 6 III : ECONOMIC POLICIES AND STRATEGIES............................................................................. 7 CHAPTER 02 : THE GROWTH AND STRUCTURE OF THE MALAYSIAN ECONOMY.................................. 13 I : INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................... 13 II : STATE OF THE ECONOMY IN 1970....................................................................................... 13 III : STRUCTURE OF PRODUCTION, 1971-80............................................................................ 14 IV : SOURCES OF GROWTH........................................................................................................ 20 V : TERMS OF TRADE AND CHANGES IN REAL INCOMES....................................................... 25 VI : SAVINGS AND INVESTMENT............................................................................................... -

TITLE Fulbright-Hays Seminars Abroad Program: Malaysia 1995

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 405 265 SO 026 916 TITLE Fulbright-Hays Seminars Abroad Program: Malaysia 1995. Participants' Reports. INSTITUTION Center for International Education (ED), Washington, DC.; Malaysian-American Commission on Educational Exchange, Kuala Lumpur. PUB DATE 95 NOTE 321p.; Some images will not reproduce clearly. PUB TYPE Guides Non-Classroom Use (055) Reports Descriptive (141) Collected Works General (020) EDRS PRICE MFO1 /PC13 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Area Studies; *Asian History; *Asian Studies; Cultural Background; Culture; Elementary Secondary Education; Foreign Countries; Foreign Culture; *Global Education; Human Geography; Instructional Materials; *Non Western Civilization; Social Studies; *World Geography; *World History IDENTIFIERS Fulbright Hays Seminars Abroad Program; *Malaysia ABSTRACT These reports and lesson plans were developed by teachers and coordinators who traveled to Malaysia during the summer of 1995 as part of the U.S. Department of Education's Fulbright-Hays Seminars Abroad Program. Sections of the report include:(1) "Gender and Economics: Malaysia" (Mary C. Furlong);(2) "Malaysia: An Integrated, Interdisciplinary Social Studies Unit for Middle School/High School Students" (Nancy K. Hof);(3) "Malaysian Adventure: The Cultural Diversity of Malaysia" (Genevieve M. Homiller);(4) "Celebrating Cultural Diversity: The Traditional Malay Marriage Ritual" (Dorene H. James);(5) "An Introduction of Malaysia: A Mini-unit for Sixth Graders" (John F. Kennedy); (6) "Malaysia: An Interdisciplinary Unit in English Literature and Social Studies" (Carol M. Krause);(7) "Malaysia and the Challenge of Development by the Year 2020" (Neale McGoldrick);(8) "The Iban: From Sea Pirates to Dwellers of the Rain Forest" (Margaret E. Oriol);(9) "Vision 2020" (Louis R. Price);(10) "Sarawak for Sale: A Simulation of Environmental Decision Making in Malaysia" (Kathleen L. -

Daim: New Financial Hub Proposal Merits Consideration (NST 11/03

11/03/2000 Daim: New financial hub proposal merits consideration Hardev Kaur in Jakarta JAKARTA, Fri: The proposal for a new financial centre, possibly based in Bandar Seri Begawan, to facilitate financial transactions among Malaysia, Indonesia and Brunei, deserves serious consideration despite there being already such centres in East Asia and South-East Asia. Indonesian President Abdurrahman Wahid, who had discussed the proposal with the Sultan of Brunei recently, raised the matter during bilateral talks with Prime Minister Datuk Seri Dr Mahathir Mohamad at the Merdeka Palace yesterday. Finance Minister Tun Daim Zainuddin said details of the proposal as well as implications of the move must be studied. He was asked whether there is room for another centre, considering there are already Labuan International Offshore Financial Centre (IOFC), the Bangkok Financial Centre, Singapore, Hong Kong and Tokyo. "If there is business, why not?" Daim said. In fact, members of the East Asia Growth Area (EAGA) - Malaysia, Brunei Indonesia and the Philippines - have agreed that the Labuan IOFC serve as the financial centre for the grouping. Even so, the proposal should not be rejected outright, he said, adding that Indonesia and Brunei might have their reasons for suggesting it. When Malaysia decided to set up Labuan IOFC, it undertook several detailed studies including looking at operations of existing financial centres such as the one in the Cayman Islands. Daim is in the high-powered delegation accompanying Dr Mahathir on his two-day official visit here. The Finance Minister, who is also Special Functions Minister, held parallel discussions with his counterpart and the republic's other economic ministers. -

Multiversityconferencesingoa

Multiworld Multiversity Taleemnet A word from the editors 1 The captive mind revisited 3 Rural curriculum 9 Multiworld websites 2 The university in ruins 5 Taleemnet news 10 Mutiversity: Work in progress 6 Aksharnandan 11 Multiversity news 7 Vernacular educators 12 Dharampal 8 Educating differently 14 First person: David Hogg 16 2007 Vol.II No.4 A word from the editor Kamiriithu – Multiversity’s critical and no-holds-barred journal on learning and education – is rejuvenated and, after a considerable lapse of time, back again in your hands. Sorry for the inordinate delay. It was never thought we would be short of both: hands and minds. How do small fry like us compete with call centres? Since we had at the very beginning announced we would bring out issues only if and when we had quality stuff, we decided to sit tight and wait for more propitious times and people. Those have finally arrived. Good sense will always prevail. The re-appearance of Kamiriithu is therefore an occasion to rejoice. On the other hand, we must weep as well: in more recent months, we have lost forever two beacon lights – the distinguished Indian historian, Dharampal, and the pioneering Malaysian social scientist, Syed Hussein Alatas. The departure of these two truly inspiring individuals is a gentle but firm reminder that we are not working S with eternal time-frames to bring about the changes we desire. Dharampal and Alatas provided pioneering leadership on how we might become ourselves again. Both MUNDO contributed in a substantial way to redefining or altering our perceptions of the world, one through history, the other through sociology. -

Remarks by the Honorable Datuk Seri Syed Hamid Albar

By : DATUK SERI SYED HAMID ALBAR Venue : PUTRAJAYA Date : 22 APRIL 2004 Title : REMARKS AT THE OPENING CEREMONY OF THE SPECIAL MEETING OF THE OIC ON THE MIDDLE EAST The Honorable Dato' Seri Abdullah Ahmad Badawi Prime Minister of Malaysia H.E. Dr Abdelouahed Belkeziz, Secretary General of OIC Excellencies Ladies and Gentlemen Assalamu'alaikum Warahmatullahhibarokatuh, I would like to thank The Honorable Dato' Seri Abdullah Ahmad Badawi, Prime Minister of Malaysia today for his presence at this Special Meeting. I also thank delegates from other countries for their attendance. I know we have given very short notice but your attendance shows the importance and relevancy for this meeting to be held. As Chairman of the 10th OIC summit, Malaysia feels duty bound to call for this meeting amidst the problems and crisis facing the Muslim world and the Ummah. We witness the continued violence in the Middle East, be it in Palestine or Iraq and we also witness the arrogance of power and total disregard for international law and the multilateral process. In other words, we are facing all kinds of pressures in our intention of giving credibility and integrity to the Islamic Ummah. What is obvious is that there is a need for unity and cohesion amongst the Muslims if they want to be counted in the global affairs. Failing to do this would mean that we would continue to be sidelined, marginalized and deprived in making decisions for our own future. Others will instead make it for us. Finally, it is in this context that Malaysia has called for this special Meeting, hoping that in the spirit of brotherhood and unity, we will be able to sit down together to look at ourselves and chart our plans. -

Malaysia: the 2020 Putsch for Malay Islam Supremacy James Chin School of Social Sciences, University of Tasmania

Malaysia: the 2020 putsch for Malay Islam supremacy James Chin School of Social Sciences, University of Tasmania ABSTRACT Many people were surprised by the sudden fall of Mahathir Mohamad and the Pakatan Harapan (PH) government on 21 February 2020, barely two years after winning the historic May 2018 general elections. This article argues that the fall was largely due to the following factors: the ideology of Ketuanan Melayu Islam (Malay Islam Supremacy); the Mahathir-Anwar dispute; Mahathir’s own role in trying to reduce the role of the non-Malays in the government; and the manufactured fear among the Malay polity that the Malays and Islam were under threat. It concludes that the majority of the Malay population, and the Malay establishment, are not ready to share political power with the non- Malays. Introduction Many people were shocked when the Barisan National (BN or National Front) govern- ment lost its majority in the May 2018 general elections. After all, BN had been in power since independence in 1957 and the Federation of Malaysia was generally regarded as a stable, one-party regime. What was even more remarkable was that the person responsible for Malaysia’s first regime change, Mahathir Mohammad, was also Malaysia’s erstwhile longest serving prime minister. He had headed the BN from 1981 to 2003 and was widely regarded as Malaysia’s strongman. In 2017, he assumed leader- ship of the then-opposition Pakatan Harapan (PH or Alliance of Hope) coalition and led the coalition to victory on 9 May 2018. He is remarkable as well for the fact that he became, at the age of 93, the world’s oldest elected leader.1 The was great hope that Malaysia would join the global club of democracy but less than two years on, the PH government fell apart on 21 February 2020. -

The 1Malaysia Development Berhad (1MDB) Scandal: Exploring Malaysia's 2018 General Elections and the Case for Sovereign Wealth Funds

Seattle Pacific University Digital Commons @ SPU Honors Projects University Scholars Spring 6-7-2021 The 1Malaysia Development Berhad (1MDB) Scandal: Exploring Malaysia's 2018 General Elections and the Case for Sovereign Wealth Funds Chea-Mun Tan Seattle Pacific University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.spu.edu/honorsprojects Part of the Economics Commons, and the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Tan, Chea-Mun, "The 1Malaysia Development Berhad (1MDB) Scandal: Exploring Malaysia's 2018 General Elections and the Case for Sovereign Wealth Funds" (2021). Honors Projects. 131. https://digitalcommons.spu.edu/honorsprojects/131 This Honors Project is brought to you for free and open access by the University Scholars at Digital Commons @ SPU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ SPU. The 1Malaysia Development Berhad (1MDB) Scandal: Exploring Malaysia’s 2018 General Elections and the Case for Sovereign Wealth Funds by Chea-Mun Tan First Reader, Dr. Doug Downing Second Reader, Dr. Hau Nguyen A project submitted in partial fulfillMent of the requireMents of the University Scholars Honors Project Seattle Pacific University 2021 Tan 2 Abstract In 2015, the former PriMe Minister of Malaysia, Najib Razak, was accused of corruption, eMbezzleMent, and fraud of over $700 million USD. Low Taek Jho, the former financier of Malaysia, was also accused and dubbed the ‘mastermind’ of the 1MDB scandal. As one of the world’s largest financial scandals, this paper seeks to explore the political and economic iMplications of 1MDB through historical context and a critical assessMent of governance. Specifically, it will exaMine the economic and political agendas of former PriMe Ministers Najib Razak and Mahathir MohaMad. -

71 Land Settlement Schemes and the Alleviation of Rural Poverty In

Land Settlement Schemes and the Alleviation of Rural Poverty in Sarawak, East Malaysia: A Critical Commentary Victor T. King Universit of Hull Introduction For a long time now the Malaysian government, the Sarawak state authorities and several outside agencies and observers have recognised that one of the main tasks which modern Sarawak faces is the improvement of its agricultural sector and the alleviation of rural poverty. Much of what James Jackson said in the mid-1960s, in his outstanding geographical study of Sarawak, is still of relevance today. The extension and improvement of farming is the cornerstone , of development planning in Sarawak for, despite the recent growth of the timber industry, agriculture will remain the basis of the economy and ultimately social and economic progress depends on the upgrading of rural incomes. However, in terms of agricultural development, Sarawak faces severe difficulties. Over vast areas soils are poor, and often acid; the steep slopes characteristic of much of the interior and the extensive peat swamps of the coastal plains inhibit development and enhance costs, as does the lack of roads. The widespread existence of the bush-fallow method of hill-padi farming presents a complex and urgent problem which must be solved before agricultural development can proceed much further in interior areas. Train- ing schemes are required to overcome the general ignorance of good farming practices and there is a shortage of suitable staff. Finally, development is hampered by land-tenure problems. (1968: 73-74) Government planning in Sarawak must be seen in the context of the wider Federa- tion of Malaysia's New Economic Policy, initiated with the Second Malaysia Plan (1971-75).