CSCHS Newsletter Fall/Winter 2008

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27

1 MARK ROSENBAUM [SBN 59940] T.E. GLENN [SBN 155761] [email protected] [email protected] 2 KATHRYN EIDMANN [SBN 268053] DOUGLAS G. CARNAHAN [email protected] [SBN 65395] 3 LORRAINE LOPEZ [SBN 273612] [email protected] [email protected] INDIRA CAMERON-BANKS 4 JOANNA ADLER [SBN 318306] [SBN 248634] [email protected] [email protected] 5 JESSELYN FRILEY [SBN 319198] INNER CITY LAW CENTER [email protected] 1309 East 7th Street 6 PUBLIC COUNSEL Los Angeles, CA 90021 610 South Ardmore Avenue Telephone: (213) 891-3275 7 Los Angeles, CA 90005 Facsimile: (213) 891-2888 Telephone: (213) 385-2977 8 Facsimile: (213) 385-9089 Attorneys for Plaintiff INNER CITY LAW CENTER 9 Attorneys for Plaintiff PUBLIC COUNSEL 10 Additional counsel listed on next page 11 12 SUPERIOR COURT OF CALIFORNIA, LOS ANGELES 13 PUBLIC COUNSEL, on behalf of itself Case No. 14 and its clients; INNER CITY LAW CENTER, on behalf of itself and its 15 clients; NEIGHBORHOOD LEGAL SERVICES OF LOS ANGELES COMPLAINT FOR 16 COUNTY, on behalf of itself and its DECLARATORY AND clients; BET TZEDEK, on behalf of INJUNCTIVE RELIEF 17 itself and its clients; LEGAL AID FOUNDATION OF LOS ANGELES, 18 on behalf of itself and its clients, 19 Plaintiffs, 20 v. 21 PRESIDING JUDGE, SUPERIOR COURT OF LOS ANGELES 22 COUNTY, in his or her official capacity; CLERK OF COURT, 23 SUPERIOR COURT OF LOS ANGELES COUNTY, in his or her 24 official capacity. 25 Defendants. 26 27 28 COMPLAINT FOR DECLARATORY AND INJUNCTIVE RELIEF 1 TRINIDAD OCAMPO [SBN 256217] [email protected] 2 ANA A. -

Publication and Depublication of California Court of Appeal Opinions: Is the Eraser Mightier Than the Pencil? Gerald F

Santa Clara Law Santa Clara Law Digital Commons Faculty Publications Faculty Scholarship 1-1-1992 Publication and Depublication of California Court of Appeal Opinions: Is the Eraser Mightier than the Pencil? Gerald F. Uelmen Santa Clara University School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.scu.edu/facpubs Recommended Citation 26 Loy. L. A. L. Rev. 1007 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Santa Clara Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Santa Clara Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PUBLICATION AND DEPUBLICATION OF CALIFORNIA COURT OF APPEAL OPINIONS: IS THE ERASER MIGHTIER THAN THE PENCIL? Gerald F. Uelmen* What is a modem poet's fate? To write his thoughts upon a slate; The critic spits on what is done, Gives it a wipe-and all is gone.' I. INTRODUCTION During the first five years of the Lucas court,2 the California Supreme Court depublished3 586 opinions of the California Court of Ap- peal, declaring what the law of California was not.4 During the same five-year period, the California Supreme Court published a total of 555 of * Dean and Professor of Law, Santa Clara University School of Law. B.A., 1962, Loyola Marymount University; J.D., 1965, LL.M., 1966, Georgetown University Law Center. The author would like to acknowledge the assistance of Patrick Martucci, J.D., 1993, Santa Clara University School of Law, in the research for this Article. -

Lasc to Open Courtrooms April 16 at Historic Spring Street Federal Courthouse in Downtown Los Angeles

Los Angeles Superior Court – Public Information Office 111 N. Hill Street, Room 107, Los Angeles, CA 90012 [email protected] www.lacourt.org NEWS RELEASE March 8, 2018 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE LASC TO OPEN COURTROOMS APRIL 16 AT HISTORIC SPRING STREET FEDERAL COURTHOUSE IN DOWNTOWN LOS ANGELES The Los Angeles Superior Court (LASC) has announced that the complex civil litigation program located at Central Civil West (CCW) Courthouse and some civil courtrooms at the Stanley Mosk Courthouse will relocate to the historic Spring Street Federal Courthouse, located at 312 N. Spring St., Los Angeles, in mid-April, with hearings set to begin April 16. Designed by Gilbert Stanley Underwood and Louis A. Simon as a major example of Art Moderne architecture, the Spring Street Courthouse was completed in 1940 and originally served as both a courthouse and post office. It was the third federal building constructed in Los Angeles to serve its rapidly growing population in the early twentieth century. Since the mid-1960s, it has functioned solely as a courthouse, most recently for judges from the United States District Court, Central District of California before their relocation in 2016 to the new First Street Federal Courthouse in downtown Los Angeles. “Relocating to the Spring Street Courthouse will enable us to expand access to justice,” said LASC Presiding Judge Daniel J. Buckley. “LASC is honored to help preserve this national historic landmark as a place for the administration of justice.” Savings from the relocation of the complex litigation program will offset much of the costs of the Spring Street Courthouse lease, providing opportunities for expanding courtrooms without additional cost. -

The California Recall History Is a Chronological Listing of Every

Complete List of Recall Attempts This is a chronological listing of every attempted recall of an elected state official in California. For the purposes of this history, a recall attempt is defined as a Notice of Intention to recall an official that is filed with the Secretary of State’s Office. 1913 Senator Marshall Black, 28th Senate District (Santa Clara County) Qualified for the ballot, recall succeeded Vote percentages not available Herbert C. Jones elected successor Senator Edwin E. Grant, 19th Senate District (San Francisco County) Failed to qualify for the ballot 1914 Senator Edwin E. Grant, 19th Senate District (San Francisco County) Qualified for the ballot, recall succeeded Vote percentages not available Edwin I. Wolfe elected successor Senator James C. Owens, 9th Senate District (Marin and Contra Costa counties) Qualified for the ballot, officer retained 1916 Assemblyman Frank Finley Merriam Failed to qualify for the ballot 1939 Governor Culbert L. Olson Failed to qualify for the ballot Governor Culbert L. Olson Filed by Olson Recall Committee Failed to qualify for the ballot Governor Culbert L. Olson Filed by Citizens Olson Recall Committee Failed to qualify for the ballot 1940 Governor Culbert L. Olson Filed by Olson Recall Committee Failed to qualify for the ballot Governor Culbert L. Olson Filed by Olson Recall Committee Failed to qualify for the ballot 1960 Governor Edmund G. Brown Filed by Roderick J. Wilson Failed to qualify for the ballot 1 Complete List of Recall Attempts 1965 Assemblyman William F. Stanton, 25th Assembly District (Santa Clara County) Filed by Jerome J. Ducote Failed to qualify for the ballot Assemblyman John Burton, 20th Assembly District (San Francisco County) Filed by John Carney Failed to qualify for the ballot Assemblyman Willie L. -

3A APPDX B Attachments

APPENDIX B ATTACHMENT 1 County Courthouses and Other Sheriff’s Facilities – Location and Address Central Bureau Central Arraignment Courts 429 Bauchet St., Los Angeles, CA 90012 Central Civil West Courthouse 600 South Commonwealth Ave., Los Angeles, CA 90005 Clara Shortridge Foltz Criminal Justice Center 210 West Temple Street, Los Angeles, CA 90012 Hollywood Courthouse 5925 Hollywood Blvd., Los Angeles, CA 90028 Metropolitan Courthouse 1945 South Hill Street, Los Angeles, CA 90007 Stanley Mosk Courthouse 111 North Hill Street, Los Angeles, CA 90012 East Bureau Alhambra Courthouse 150 West Commonwealth, Alhambra, CA 91801 Bellflower Courthouse 10025 East Flower Street, Bellflower, CA 90706 Burbank Courthouse 300 East Olive, Burbank, CA 91502 Compton Courthouse 200 West Compton Blvd., Compton, CA 90220 Downey Courthouse 7500 East Imperial Highway, Downey, CA 90242 East Los Angeles Courthouse 4848 E. Civic Center Way , Los Angeles, CA 90022 Eastlake Juvenile Court 1601 Eastlake Avenue, Los Angeles, CA 90033 Edmund D. Edelman Children's Court 201 Centre Plaza Drive, Monterey Park, CA 91754 El Monte Courthouse 11234 East Valley Blvd., El Monte, CA 91731 Glendale Courthouse 600 East Broadway, Glendale, CA 91206 Huntington Park Courthouse 6548 Miles Ave., Huntington Park, CA 90255 Kenyon Juvenile Justice Center 7625 South Central Avenue, Los Angeles, CA 90001 Los Padrinos Juvenile Courthouse 7281 East Quill Drive, Downey, CA 90242 Mental Health Dept. 95 Courthouse 1150 North San Fernando Rd, Los Angeles, CA 90065 Norwalk Courthouse 12720 Norwalk Blvd., Norwalk, CA 90650 Pasadena Courthouse 300 East Walnut Ave., Pasadena, CA 91101 Pomona Courthouse North 350 West Mission Blvd., Pomona, CA 91766 County of Los Angeles Appendix B – Attachment 1 Sheriff’s Department As-Needed Security Guard Services APPENDIX B ATTACHMENT 1 Pomona Courthouse South 400 Civic Center Plaza, Pomona, CA 91766 West Covina Courthouse 1427 West Covina Parkway, West Covina, CA 91790 Whittier Courthouse 7339 South Painter Ave., Whittier, CA 90602 West Bureau Airport Courthouse 11701 S. -

Central City Historic Districts, Planning Districts and Multi-Property Resources - 09/02/16

Central City Historic Districts, Planning Districts and Multi-Property Resources - 09/02/16 Districts Name: Fifth Street Single-Room Occupancy Hotel Historic District Description: The Fifth Street Single-Room Occupancy Hotel Historic District is located in the area of Downtown Los Angeles that is known as both Central City East and Skid Row. The district is small in size and rectangular in shape. It includes parcels on the north side of Fifth Street between Gladys Avenue on the east and Crocker Street on the west. Within the district are 10 properties, of which 7 (70%) contribute to its significance. The district is composed primarily of Single-Room Occupancy (SRO) hotels that were constructed between 1906 and 1922, but also includes an office building that was constructed in 1922 and two examples of infill development that date to the postwar period. Buildings occupy rectangular parcels, are flush with the street, and rise between three and seven stories in height. Most are modest and architecturally vernacular, though some exhibit some subtle references to the Beaux Arts and Italianate styles. Common architectural features include brick and masonry exteriors, flat roofs, symmetrical facades, simple cornices and dentil moldings, and articulated belt courses. Some buildings also feature fire escapes. Common alterations include storefront modifications, the alteration or removal of parapets, and the replacement of original windows and doors. This stretch of Fifth Street adheres to the skewed rectilinear street grid on which most of Downtown Los Angeles is oriented. Streetscape features are limited, and consist of concrete sidewalks that are intermittently planted with sycamore and ficus trees. -

Contents SCHOOL of LAW

UCLA Contents SCHOOL OF LAW THE MAGAZINE OF THE SCHOOL OF LAW V OL. 25–NO. 1 FALL 2001 2 A MESSAGE FROM DEAN JONATHAN D. VARAT UCLA Magazine 2002 Regents of the University of California 4 THE JUDGES OF UCLA LAW UCLA School of Law 12 JUDGES AS ALTRUISTIC HIERARCHS Box 951476 Sidebars: Los Angles, California 90095-1476 Externships for Students in Judges’ Chambers Faculty who have clerked Jonathan D. Varat, Dean Kerry A. Bresnahan ‘89, Assistant Dean, External Affairs David Greenwald, Editorial Director for Marketing and 16 FACULTY Communications Services, UCLA Recent Publications by the Faculty Regina McConahay, Director of Communications, Kenneth Karst gives keynote address at the Jefferson Memorial Lecture UCLA School of Law William Rubenstein wins the Rutter Award Francisco A. Lopez, Manager of Publications and Graphic Grant Nelson honored with the University Distinguished Teaching Award Design Donna Colin, Director of Major Gifts Gary Blasi receives two awards Charles Cannon, Director of Annual and Special Giving Law Day Shines on Michael Asimow and Paul Bergman Kristine Werlinich, Director of Alumni Relations Teresa Estrada-Mullaney ‘77 and Laura Gomez conduct workshop on The Castle Press, Printer Institutional Racism Design,Tricia Rauen, Treehouse Design and Betty Adair, The Castle Press Photographers,Todd Cheney, Regina McConahay, Scott 25 MAJOR GIFTS Leadership in the Development office: Quintard, Bill Short and Mary Ann Stuehrmann 1 Assistant Dean Kerry Bresnahan ‘89 UCLA School of Law Board of Advisors Director of Major Gifts Donna Colin Michael Masin ’69, Co-Chair Director of Annual and Special Giving Charles Cannon Kenneth Ziffren ’65, Co-Chair William M. -

Style and Correspondence Guide

STYLE AND CORRESPONDENCE GUIDE DECEMBER 2015 STYLE AND CORRESPONDENCE GUIDE DECEMBER 2015 Prepared by Editing Group Judicial Council Support PREFACE The revised Style and Correspondence Guide now consists of three major parts: Part I, Basic Formatting, presents the standard formatting guidelines for all documents and provides tips for using agency templates. Part II, Style Guide, helps staff maintain consistency and correctness in written materials, including correspondence, reports, publications, and web content. The style guide serves as an addendum to the California Style Manual1 and also reflects instances in which the Style and Correspondence Guide diverges from that manual. It should be followed in all written staff work, including correspondence, reports, and print and electronic publications. Part III, Letters and Memos, helps staff prepare correspondence that complies with judicial branch protocols and agency standards. Information and forms for submitting documents for signature by the Chief Justice or the members of the Executive Team, for requesting their attendance at events, and for submitting proposed talking points are on the Hub in Forms > Forms for Chief Justice and Executive Office. The guide follows the American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, 5th edition (2011), for hyphenation, word division, and preferred spellings. Many of the preferred spellings are incorporated into the A–Z List of Terms in Part II of this guide. The Letters and Memos section has been informed by the Gregg Reference Manual, 9th edition. For legal citations, the guide first follows the California Style Manual, 4th edition, for legal citations, then the Bluebook: A Uniform System of Citation. Four types of icons aid your use of the guide: IMPORTANT signals especially important information. -

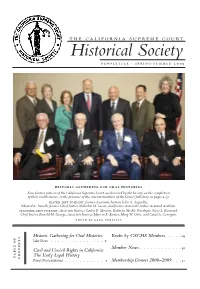

CSCHS Newsletter Spring/Summer 2009

The California Supreme Court Historical Society newsletter · s p r i n g / s u m m e r 2 0 0 9 Historic Gathering for Oral Histories Four former justices of the California Supreme Court are honored by the Society on the completion of their oral histories, in the presence of the current members of the Court (full story on pages 2–3). Seated, left to Right: former Associate Justices John A. Arguelles, Edward A. Panelli, former Chief Justice Malcolm M. Lucas, and former Associate Justice Armand Arabian. Standing, left to Right: Associate Justices Carlos R. Moreno, Kathryn Mickle Werdegar, Joyce L. Kennard, Chief Justice Ronald M. George, Associate Justices Marvin R. Baxter, Ming W. Chin, and Carol A. Corrigan. Photo by Greg Verville Historic Gathering for Oral Histories Books by CSCHS Members ��� ��� ��� ��� 29 Jake Dear ��� ��� ��� ��� ��� ��� ��� 2 Member News ��� ��� ��� ��� ��� ��� 30 Civil and Uncivil Rights in California: The Early Legal History t a b l e o f c o n t e n t s Panel Presentations ��� ��� ��� ��� ��� 4 Membership Donors 2008–2009 ��� ��� ��� 31 Historic Gathering for Oral Histories By Jake Dear Chief Supervising Attorney, California Supreme Court our former members of the California Supreme said the Chief Justice. “Over a period of many years, oral FCourt were honored by the Society and the current history interviews have been conducted of Chief Jus- justices of the Court at a ceremony celebrating the com- tice Gibson, as well as Justices Carter, Mosk, Newman, pletion of the retired justices’ oral histories. Immedi- Broussard, Reynoso, and Grodin. Through these under- ately following the Court’s April 7, 2009, session in Los takings, we have literally preserved the living history Angeles, the Court joined with Society board members of the Court and its members. -

Meeting Date April 12, 2021 [email protected]

Meeting Documents Meeting Date April 12, 2021 www.courts.ca.gov/tcfmac.htm [email protected] Request for ADA accommodations should be made at least three business days before the meeting and directed to: [email protected] T RIAL C OURT F ACILITY M ODIFICATION A DVISORY C OMMITTEE N OTICE AND A GENDA OF O PEN M EETING WITH C LOSED S ESSION Open to the Public Unless Indicated as Closed (Cal. Rules of Court, rule 10.75(c), (d), and (e)(1)) THIS MEETING IS BEING CONDUCTED BY ELECTRONIC MEANS OPEN PORTION OF THIS MEETING IS BEING RECORDED Date: April 12, 2021 Time: 10:00 – 3:30 Public Call-In Number: 1-877-820-7831; passcode 4502468 (Listen Only) Meeting materials for open portions of the meeting will be posted on the advisory body web page on the California Courts website at least three business days before the meeting. Members of the public seeking to make an audio recording of the open meeting portion of the meeting must submit a written request at least two business days before the meeting. Requests can be e-mailed to [email protected]. Agenda items are numbered for identification purposes only and will not necessarily be considered in the indicated order. I. O PEN MEETING ( C AL. R ULES OF C OURT, R ULE 10.75(C )(1)) Call to Order and Roll Call Approval of Minutes (Action Required) Approve minutes of the March 8, 2021 Trial Court Facility Modification Advisory Committee meeting. II. P UBLIC C OMMENT (CAL. -

Los Angeles Superior Court

2018 Annual Report Los Angeles Superior Court 2018 ANNUAL REPORT TABLE OF CONTENTS 2 A MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDING JUDGE A AND COURT EXECUTIVE OFFICER 4 ABOUT THE LOS ANGELES SUPERIOR COURT 99 YEAR IN REVIEW 6 Technology Improvements Continue 10 Expanding Access in Communities 13 Civil 16 Criminal 18 ODR Court 20 Mental Health 22 Family Law 25 Self Help 29 Probate 30 Juvenile 34 Alternate Dispute Resolution 35 Traffic 38 Jury 40 Language Access 42 Community and Diversity Outreach 46 WORKLOAD AND FINANCIAL DATA 50 COURT LOCATIONS AND CONTACTS Photo: The newly opened Los Angeles Superior Court at United States Court House. LOS ANGELES SUPERIOR COURT 1 2018 ANNUAL REPORT A MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDING JUDGE AND COURT EXECUTIVE OFFICER As the only state trial court for the County of Los Angeles, the Los Angeles Superior Court provides access to justice for millions of people each year, across a broad range of issues. The Court: • Protects children; • Cares for those who cannot care for themselves; • Helps families in distress; • Supports California’s economic infrastructure; • Balances the need for public safety with people’s constitutional rights; and • Uses technology to better serve the public and to save scarce taxpayer dollars. The 2018 Annual Report documents some of the highlights of how the Court has improved access to justice in all of these areas. It describes how the commitment to modernizing our business processes laid a foundation for better service and cost savings—in part, through radically transforming a paper-based system into a digital one. 2 WWW.LACOURT.ORG 2018 ANNUAL REPORT The Annual Report also illustrates how the Court has transformed efficiencies and savings into more and better services for the public in every area of law and every facet of court operations. -

Making the Stanley Mosk Courthouse by Michael L

Postcard showing the front of Los Angeles County Courthouse from the corner of Grand and First Streets. Caption reads: “The new county courthouse is located at the Civic Center and is one of the finest administrative buildings found anywhere. It has been planned for the enormous expansion and increase in population for Los Angeles County.” Department of Archives and Special Collections, William H. Hannon Library, Loyola Marymount University Making the Stanley Mosk Courthouse by Michael L. Stern* ore than 60 years have passed since the The first Los Angeles courthouse was the humble dedication of Los Angeles’ main courthouse adobe home of County Judge Agustin Olvera, a former Mby United States Supreme Court Justice Earl Mexican official who was elected in 1850 by 377 of his Warren on October 31, 1958. The construction of this new fellow citizens soon after California attained state- monumental structure with its 100 courtrooms took 25 hood. It was located on the plaza adjacent to the mis- years of diligent political action and planning by civic sion church La Iglesia de Nuestra Senora la Reina de Los and judicial leaders. Although no public ceremony Angeles, founded in 1776. With virtually no legal train- marked this anniversary, the occasion prompts us to ing and limited English, Judge Olvera used an inter- revisit the rich history of this landmark building and its preter when he presided over cases under the bilingual predecessors. first California Constitution. When the doors of Los Angeles’ fifth principal court- From 1852 to 1861, court was convened in various house opened six decades ago, it was heralded as the downtown buildings, including rented space in the “Dream Courthouse” and the “Courthouse to Last 250 judiciary’s second main home in the elegant Bella Union Years.” In 2002, the County Courthouse was renamed Hotel.