Introduction to Care of Tortoises

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Body Condition Assessment – As a Welfare and Management Assessment Tool for Radiated Tortoises (Astrochelys Radiata)

Body condition assessment – as a welfare and management assessment tool for radiated tortoises (Astrochelys radiata) Hullbedömning - som ett verktyg för utvärdering av välfärd och skötsel av strålsköldpadda (Astrochelys radiata) Linn Lagerström Independent project • 15 hp Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, SLU Department of Animal Environment and Health Programme/Education Uppsala 2020 2 Body condition assessment – as a welfare and management tool for radiated tortoises (Astrochelys radiata) Hullbedömning - som ett verktyg för utvärdering av välfärd och skötsel av strålsköldpadda (Astrochelys radiata) Linn Lagerström Supervisor: Lisa Lundin, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Department of Animal Environment and Health Examiner: Maria Andersson, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Department of Animal Environment and Health Credits: 15 hp Level: First cycle, G2E Course title: Independent project Course code: EX0894 Programme/education: Course coordinating dept: Department of Aquatic Sciences and Assessment Place of publication: Uppsala Year of publication: 2020 Cover picture: Linn Lagerström Keywords: Tortoise, turtle, radiated tortoise, Astrochelys radiata, Geochelone radiata, body condition indices, body condition score, morphometrics Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences Faculty of Natural Resources and Agricultural Sciences Department of Animal Environment and Health 3 Publishing and archiving Approved students’ theses at SLU are published electronically. As a student, you have the copyright to your own work and need to approve the electronic publishing. If you check the box for YES, the full text (pdf file) and metadata will be visible and searchable online. If you check the box for NO, only the metadata and the abstract will be visiable and searchable online. Nevertheless, when the document is uploaded it will still be archived as a digital file. -

Sexual Dimorphism of Testudo Tortoises from an Unstudied Population in Northeast Greece

Herpetology Notes, volume 12: 229-233 (2019) (published online on 26 January 2019) Sexual dimorphism of Testudo tortoises from an unstudied population in northeast Greece Konstantina N. Makridou1,*, Charalambos T. Thoma1, Dimitrios E. Bakaloudis1, and Christos G. Vlachos1 Abstract. Sexual dimorphism in tortoise species is prominent, but may vary geographically. Here, we investigated sexual dimorphism of Testudo hermanni and T. graeca from previously unstudied populations in northeast Greece. Females of each species illustrated higher mean values in almost all traits and exhibited better body condition than males. The longer tails and smaller plastron found in males of T. hermanni, and the wider anal notch found in males of T. graeca are believed to be linked with mating success and courtship behavior. When compared to other regions, both our species were found to be larger and heavier in most cases. Our results may be used in future comparative studies, providing additional insights for both species. Keywords. Testudo hermanni, Testudo graeca, morphometry, Scale mass index, Greece Introduction morphometry and sexual dimorphism of tortoises has been previously studied in several regions of Greece Sexual dimorphism in body size and shell shape is (Willemsen and Hailey, 1999, 2003), populations from prominent in tortoise species and has been shown to Evros district remain unstudied. Our results aim to offer be driven by natural selection (e.g. to increase female additional insights from a region where tortoises have fecundity), sexual selection (e.g. to increase male never been studied before and provide new data that reproductive success), or a combination of the two may be used in future comparative studies. -

Egyptian Tortoise (Testudo Kleinmanni)

EAZA Reptile Taxon Advisory Group Best Practice Guidelines for the Egyptian tortoise (Testudo kleinmanni) First edition, May 2019 Editors: Mark de Boer, Lotte Jansen & Job Stumpel EAZA Reptile TAG chair: Ivan Rehak, Prague Zoo. EAZA Best Practice Guidelines Egyptian tortoise (Testudo kleinmanni) EAZA Best Practice Guidelines disclaimer Copyright (May 2019) by EAZA Executive Office, Amsterdam. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in hard copy, machine-readable or other forms without advance written permission from the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA). Members of the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA) may copy this information for their own use as needed. The information contained in these EAZA Best Practice Guidelines has been obtained from numerous sources believed to be reliable. EAZA and the EAZA Reptile TAG make a diligent effort to provide a complete and accurate representation of the data in its reports, publications, and services. However, EAZA does not guarantee the accuracy, adequacy, or completeness of any information. EAZA disclaims all liability for errors or omissions that may exist and shall not be liable for any incidental, consequential, or other damages (whether resulting from negligence or otherwise) including, without limitation, exemplary damages or lost profits arising out of or in connection with the use of this publication. Because the technical information provided in the EAZA Best Practice Guidelines can easily be misread or misinterpreted unless properly analysed, EAZA strongly recommends that users of this information consult with the editors in all matters related to data analysis and interpretation. EAZA Preamble Right from the very beginning it has been the concern of EAZA and the EEPs to encourage and promote the highest possible standards for husbandry of zoo and aquarium animals. -

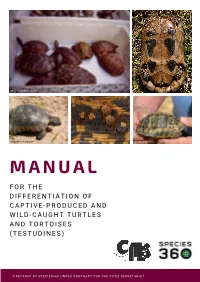

Manual for the Differentiation of Captive-Produced and Wild-Caught Turtles and Tortoises (Testudines)

Image: Peter Paul van Dijk Image:Henrik Bringsøe Image: Henrik Bringsøe Image: Andrei Daniel Mihalca Image: Beate Pfau MANUAL F O R T H E DIFFERENTIATION OF CAPTIVE-PRODUCED AND WILD-CAUGHT TURTLES AND TORTOISES (TESTUDINES) PREPARED BY SPECIES360 UNDER CONTRACT FOR THE CITES SECRETARIAT Manual for the differentiation of captive-produced and wild-caught turtles and tortoises (Testudines) This document was prepared by Species360 under contract for the CITES Secretariat. Principal Investigators: Prof. Dalia A. Conde, Ph.D. and Johanna Staerk, Ph.D., Species360 Conservation Science Alliance, https://www.species360.orG Authors: Johanna Staerk1,2, A. Rita da Silva1,2, Lionel Jouvet 1,2, Peter Paul van Dijk3,4,5, Beate Pfau5, Ioanna Alexiadou1,2 and Dalia A. Conde 1,2 Affiliations: 1 Species360 Conservation Science Alliance, www.species360.orG,2 Center on Population Dynamics (CPop), Department of Biology, University of Southern Denmark, Denmark, 3 The Turtle Conservancy, www.turtleconservancy.orG , 4 Global Wildlife Conservation, globalwildlife.orG , 5 IUCN SSC Tortoise & Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group, www.iucn-tftsG.org. 6 Deutsche Gesellschaft für HerpetoloGie und Terrarienkunde (DGHT) Images (title page): First row, left: Mixed species shipment (imaGe taken by Peter Paul van Dijk) First row, riGht: Wild Testudo marginata from Greece with damaGe of the plastron (imaGe taken by Henrik BrinGsøe) Second row, left: Wild Testudo marginata from Greece with minor damaGe of the carapace (imaGe taken by Henrik BrinGsøe) Second row, middle: Ticks on tortoise shell (Amblyomma sp. in Geochelone pardalis) (imaGe taken by Andrei Daniel Mihalca) Second row, riGht: Testudo graeca with doG bite marks (imaGe taken by Beate Pfau) Acknowledgements: The development of this manual would not have been possible without the help, support and guidance of many people. -

The Conservation Biology of Tortoises

The Conservation Biology of Tortoises Edited by Ian R. Swingland and Michael W. Klemens IUCN/SSC Tortoise and Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group and The Durrell Institute of Conservation and Ecology Occasional Papers of the IUCN Species Survival Commission (SSC) No. 5 IUCN—The World Conservation Union IUCN Species Survival Commission Role of the SSC 3. To cooperate with the World Conservation Monitoring Centre (WCMC) The Species Survival Commission (SSC) is IUCN's primary source of the in developing and evaluating a data base on the status of and trade in wild scientific and technical information required for the maintenance of biological flora and fauna, and to provide policy guidance to WCMC. diversity through the conservation of endangered and vulnerable species of 4. To provide advice, information, and expertise to the Secretariat of the fauna and flora, whilst recommending and promoting measures for their con- Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna servation, and for the management of other species of conservation concern. and Flora (CITES) and other international agreements affecting conser- Its objective is to mobilize action to prevent the extinction of species, sub- vation of species or biological diversity. species, and discrete populations of fauna and flora, thereby not only maintain- 5. To carry out specific tasks on behalf of the Union, including: ing biological diversity but improving the status of endangered and vulnerable species. • coordination of a programme of activities for the conservation of biological diversity within the framework of the IUCN Conserva- tion Programme. Objectives of the SSC • promotion of the maintenance of biological diversity by monitor- 1. -

Indian Star Tortoise Care

RVC Exotics Service Royal Veterinary College Royal College Street London NW1 0TU T: 0207 554 3528 F: 0207 388 8124 www.rvc.ac.uk/BSAH INDIAN STAR TORTOISE CARE Indian star tortoises originate from the semi-arid dry grasslands of Indian subcontinent. They can be easily recognised by the distinctive star pattern on their bumpy carapace. Star tortoises are very sensitive to their environmental conditions and so not recommended for novice tortoise owners. It is important to note that these tortoises do not hibernate. HOUSING • Tortoises make poor vivarium subjects. Ideally a floor pen or tortoise table should be created. This needs to have solid sides (1 foot high) for most tortoises. Many are made out of wood or plastic. A large an area as possible should be provided, but as the size increases extra basking sites will need to be provided. For a small juvenile at least 90 cm (3 feet) long x 30 cm (1 foot) wide is recommended. This is required to enable a thermal gradient to be created along the length of the tank (hot to cold). • Hides are required to provide some security. Artificial plants, cardboard boxes, plant pots, logs or commercially available hides can be used. They should be placed both at the warm and cooler ends of the tank. • Substrates suitable for housing tortoises include newspaper, Astroturf, and some of the commercially available substrates. Natural substrate such as soil may also be used to allow for digging. It is important that the substrates either cannot be eaten, or if they are, do not cause blockages as this can prove fatal. -

Aldabrachelys Arnoldi (Bour 1982) – Arnold's Giant Tortoise

Conservation Biology of Freshwater Turtles and Tortoises: A Compilation ProjectTestudinidae of the IUCN/SSC — AldabrachelysTortoise and Freshwater arnoldi Turtle Specialist Group 028.1 A.G.J. Rhodin, P.C.H. Pritchard, P.P. van Dijk, R.A. Saumure, K.A. Buhlmann, J.B. Iverson, and R.A. Mittermeier, Eds. Chelonian Research Monographs (ISSN 1088-7105) No. 5, doi:10.3854/crm.5.028.arnoldi.v1.2009 © 2009 by Chelonian Research Foundation • Published 18 October 2009 Aldabrachelys arnoldi (Bour 1982) – Arnold’s Giant Tortoise JUSTIN GERLACH 1 1133 Cherry Hinton Road, Cambridge CB1 7BX, United Kingdom [[email protected]] SUMMARY . – Arnold’s giant tortoise, Aldabrachelys arnoldi (= Dipsochelys arnoldi) (Family Testudinidae), from the granitic Seychelles, is a controversial species possibly distinct from the Aldabra giant tortoise, A. gigantea (= D. dussumieri of some authors). The species is a morphologi- cally distinctive morphotype, but has so far not been genetically distinguishable from the Aldabra tortoise, and is considered synonymous with that species by many researchers. Captive reared juveniles suggest that there may be a genetic basis for the morphotype and more detailed genetic work is needed to elucidate these relationships. The species is the only living saddle-backed tortoise in the Seychelles islands. It was apparently extirpated from the wild in the 1800s and believed to be extinct until recently purportedly rediscovered in captivity. The current population of this morphotype is 23 adults, including 18 captive adult males on Mahé Island, 5 adults recently in- troduced to Silhouette Island, and one free-ranging female on Cousine Island. Successful captive breeding has produced 138 juveniles to date. -

Current Trends in the Husbandry and Veterinary Care of Tortoises Siuna A

Current trends in the husbandry and veterinary care of tortoises Siuna A. Reid BVMS CertAVP(ZooMed) MRCVS Presented to the BCG symposium at the Open University, Milton Keynes on 25th March 2017 Introduction Tortoises have been kept as pets for centuries but have recently gained even more popularity now that there has been an increase in the number of domestically bred tortoises. During the 1970s there was the beginning of a movement to change the law and also the birth of the British Chelonia Group. A small group of forward thinking reptile keepers and vets began to realise that more had to be done to care for and treat this group of pets. They also recognized the drawbacks of the legislation in place under the Department of the Environment, restricting the numbers of tortoises being imported to 100,000 per annum and a minimum shell length of 4 inches (10.2cm). Almost all tortoises were wild caught and husbandry and hibernation meant surviving through the summer in preparation for five to six months of hibernation. With the gradual decline in wild caught tortoises, this article compares the husbandry and veterinary practice then with today’s very different husbandry methods and the problems that these entail. Importation Tortoises have been imported for hundreds of years. The archives of the BCG have been used to loosely sum up the history of tortoise keeping in the UK. R A tortoise was bought for 2s/6d from a sailor in 1740 (Chatfield 1986) R Records show as early as the 1890s tortoises were regularly being brought to the UK R In 1951 250 surplus tortoises were found dumped in a street in London –an application for a ban was refused R In 1952 200,000 tortoises were imported R In 1978 the RSPCA prosecuted a Japanese restaurant for cooking a tortoise – boiled alive (Vodden 1983) R In 1984 a ban on importation of Mediterranean tortoises was finally approved 58 © British Chelonia Group + Siuna A. -

Chelonoidis Chathamensis)

Volume 6 • 2018 10.1093/conphys/coy004 Research article Biochemistry and hematology parameters of the San Cristóbal Galápagos tortoise (Chelonoidis chathamensis) Gregory A. Lewbart1,*, John A. Griffioen1, Alison Savo1, Juan Pablo Muñoz-Pérez2, Carlos Ortega3, Andrea Loyola3, Sarah Roberts1, George Schaaf1, David Steinberg4, Steven B. Osegueda2, Michael G. Levy1 and Diego Páez-Rosas2,3 1College of Veterinary Medicine, North Carolina State University, 1060 William Moore Drive, Raleigh, NC 27601, USA 2Galápagos Science Center, University San Francisco de Quito, Av. Alsacio Northia, Isla San Cristobal, Galápagos, Ecuador 3Dirección Parque Nacional Galápagos, Galapagos, Ecuador 4Department of Biology, University of North Carolina, Coker Hall, Chapel Hill, NC 27599, USA *Corresponding author: College of Veterinary Medicine, Department of Clinical Sciences, North Carolina State University, 1060 William Moore Drive, Raleigh, NC 27601, USA. Email: [email protected] .............................................................................................................................................................. As part of a planned introduction of captive Galapagos tortoises (Chelonoidis chathamensis) to the San Cristóbal highland farms, our veterinary team performed thorough physical examinations and health assessments of 32 tortoises. Blood sam- ples were collected for packed cell volume (PCV), total solids (TS), white blood cell count (WBC) differential, estimated WBC and a biochemistry panel including lactate. In some cases not all of the values were obtainable but most of the tortoises have full complements of results. Despite a small number of minor abnormalities this was a healthy group of mixed age and sex tortoises that had been maintained with appropriate husbandry. This work establishes part of a scientific and tech- nical database to provide qualitative and quantitative information when establishing sustainable development strategies aimed at the conservation of Galapagos tortoises. -

Can Unwanted Suburban Tortoises Rescue Native Hawaiian Plants?

CAN UNWANTED SUBURBAN TORTOISES RESCUE NATIVE HAWAIIAN PLANTS? by David A. Burney, James O. Juvik, Lida Pigott Burney, and Tomas Diagne 104 THE TORTOISE ・ 2012 hrough a series of coincidences, surplus pet tortoises in Hawaii may end up offering a partial solution to the seemingly insurmountable challenge posed by invasive plants in the Makauwahi Cave Reserve Ton Kaua`i. This has come about through a serendipitous intersection of events in Africa, the Mascarene Islands, North America, and Hawaii. The remote Hawaiian Islands were beyond the reach of naturally dispersing island tortoises, but the niches were apparently still there. Giant flightless ducks and geese evolved on these islands with tortoise-like beaks and other adaptations as terrestrial “meso-herbivores.” Dating of these remarkable fossil remains shows that they went extinct soon after the arrival of Polynesians at the beginning of the last millennium leaving the niches for large native herbivores entirely empty. Other native birds, including important plant pollinators, and some plant species have also suffered extinction in recent centuries. This trend accelerated after European settlement ecosystem services and a complex mix of often with the introduction of many invasive alien plants conflicting stakeholder interests clearly requires and the establishment of feral ungulate populations new paradigms and new tools. such as sheep, goats, cattle, and European swine, as Lacking any native mammalian herbivores, the well as other insidious invasives such as deer, rats, majority of the over 1,000 native Hawaiian plant mongoose, feral house cats, and even mosquitoes, species on the islands have been widely regarded which transmit avian malaria to a poorly resistant in the literature as singularly lacking in defensive native avifauna. -

A Sulcata Here, a Sulcata There, a Sulcata Everywhere Text and Photography by Dave Friend, President, CTTC, Santa Barbara-Ventura Chapter

A Sulcata Tortoise (Geochelone sulcata) emerging from a burrow in its enclosure. of the African Spurred Tortoise (Geochelone sulcata) A Sulcata Here, A Sulcata There, A Sulcata Everywhere text and photography by Dave Friend, President, CTTC, Santa Barbara-Ventura Chapter n 1986 my wife and I fell in The breeder said to feed them pumpkin All the stucco along the side of the house love with the Sulcata Tor- and alfalfa. There was not a lot of diet infor- as far as they could ram was broken. The toise and decided to purchase mation available then. We did not have good male more than the female did the greater a pair. Yes, purchase. Twenty-three years luck with the breeder’s diet. They preferred damage. Our youngest son had the outside ago there were not many Sulcatas available. the Bermuda grass, rose petals and hibis- corner bedroom upstairs, every night after We found a “BREEDER” in Riverside, CA. cus flowers in the back yard. We gave them he would go to bed I could here him holler- Made the contact and brought the pair home other treats once in a while: apples, squash, ing at that %#@* turtle. The Sulcata would toI Ventura, CA. So began an adventure that and other vegetables. Pumpkin never was start ramming the side of the house. I would we still enjoy today. high on their list of treats! They also loved to go down and move him, put things in his We were told they were about seven years drink from a running hose laid on the lawn. -

Seychelles Giant Tortoise

Conservation Biology of Freshwater Turtles and Tortoises: A Compilation ProjectTestudinidae of the IUCN/SSC — Aldabrachelys Tortoise and Freshwater hololissa Turtle Specialist Group 061.1 A.G.J. Rhodin, P.C.H. Pritchard, P.P. van Dijk, R.A. Saumure, K.A. Buhlmann, J.B. Iverson, and R.A. Mittermeier, Eds. Chelonian Research Monographs (ISSN 1088-7105) No. 5, doi:10.3854/crm.5.061.hololissa.v1.2011 © 2011 by Chelonian Research Foundation • Published 31 December 2011 Aldabrachelys hololissa (Günther 1877) – Seychelles Giant Tortoise JUSTIN GERLACH 1 1133 Cherry Hinton Road, Cambridge, CB1 7BX United Kingdom [[email protected]] SUMMARY . – The Seychelles Giant Tortoise, Aldabrachelys hololissa (= Dipsochelys hololissa) (Family Testudinidae) is a controversial species possibly distinct from the Aldabra giant tor- toise, A. gigantea (= D. dussumieri of some authors). The species is a morphologically distinctive morphotype, but has so far not been genetically distinguishable from the Aldabra tortoise, and is considered by many researchers to be either synonymous with or only subspecifically distinct from that taxon. It is a domed grazing species, differing from the Aldabra tortoise in its broader shape and reduced ossification of the skeleton; it differs also from the other controversial giant tortoise in the Seychelles, the saddle-backed morphotype A. arnoldi. Aldabrachelys hololissa was apparently extirpated from the wild in the 1800s and is now known only from 37 adults, including 28 captive, 1 free-ranging on Cerf Island, and 8 on Cousine Island, 6 of which were released in 2011 along with 40 captive bred juveniles. Captive reared juveniles show that there is a presumed genetic basis to the morphotype and further genetic work is needed to elucidate this.