For Criminal Courts & Remand Advocates

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GARDEN DEPARTMENT HORTICULTURE ASSISTANT / JUNIOR TREE OFFICER Address - GARDEN DEPARTMENT, K/East Ward Office Bldg., Azad Road Gundavli, Andheri East INTRODUCTION

BRIHANMUMBAI MAHANAGARPALIKA Section 4 Manuals as per provision of RTI Act 2005 of K/East Ward GARDEN DEPARTMENT HORTICULTURE ASSISTANT / JUNIOR TREE OFFICER Address - GARDEN DEPARTMENT, K/East ward office bldg., Azad road Gundavli, Andheri East INTRODUCTION Garden & Trees The corporation has decentralized most of the main departments functioning at the city central level under Departmental Heads, and placed the relevant sections of these Departments under the Assistant Commissioner of the Ward. Horticulture Assistant & Jr. Tree Officer are the officers appointed to look after works of Garden & Trees department at ward level. Jr. Tree Officer is subordinate to Tree Officer appointed to implement various provisions of ‘The Maharashtra (Urban Areas) Protection & Preservation of Trees Act, 1975 (As modified upto 3rd November 2006). As per Central Right to Information Act 2005, Jr. Tree Officer is appointed as Public Information Officer for Trees in the ward jurisdiction and As per Maharashtra Public Records Act-2005 and Maharashtra Public Records Act Rules -2007, he is appointed as Record Officer for Trees in ward jurisdiction. As per section 63(D) of MMC Act, 1888 (As modified upto 13th November 2006), development & maintenance of public parks, gardens & recreational spaces is the discretionary duty of MCGM. Horticulture Assistant is appointed to maintain gardens, recreational grounds, play grounds in the Ward. As per Central Right to Information Act 2005, Horticulture Assistant is appointed as Public Information Officer for gardens, recreational grounds, play grounds in the ward jurisdiction and As per Maharashtra Public Records Act-2005 and Maharashtra Public Records Act Rules -2007, he is appointed as Record Officer for Trees in ward jurisdiction. -

Authored by Dr. Rajeev Kishen

Authored by Dr. Rajeev Kishen. INDIA’S HEROES Anonymous Vocabulary and key words: 1. fidgeted 2. air of thrill and enthusiasm 3. assignment had not been a drudge 4. particular trait or quality 5. wish to emulate 6. crackle of sheets 7. rapt attention 8. perspiration 9. accustomed 10. not have a flair 11. two tenures 12. battalion in counter terrorism 13. insurgency 14. arranged for his evacuation 15. courageous 16. birds chirped 17. cars honked 18. abandon his responsibilities 19. restore the heritage structure 20. welled up 21. selfless 22. class rose as one, applauding and cheering 23. uphold the virtues of peace, tolerance and selflessness The story is narrated from the third person omniscient point of view. 1 INDIA’S HEROES Students Kabir Mrs. Baruah Students fidgeted and When Kabir got up to speak, his hands shook She gave them a few shifted in their seats, slightly and beads of perspiration appeared on seconds to settle and an air of thrill and his forehead. He was not accustomed to facing down, let us begin our enthusiasm prevailed. the entire class and speaking aloud. He knew he lesson for today. Mrs. She addressed an eager did not have a flair for making speeches. Baruah beamed Mrs. class 8 A. All forty However, he had worked hard on his Baruah said hands went up in assignments and written from the depth of his wonderful, you can unison. heart. His assignments were different from the speak on a profession A crackle of sheets was others. It did not focus on one person, profession someone you like and heard as students or quality. -

Revamping the National Security Laws of India: Need of the Hour”

FINAL REPORT OF MINOR RESEARCH PROJECT “REVAMPING THE NATIONAL SECURITY LAWS OF INDIA: NEED OF THE HOUR” Principal Investigator Mr. Aman Rameshwar Mishra Assistant Professor BVDU, New Law College, Pune SUBMITTED TO UNIVERSITY GRANTS COMMISSION WESTERN REGIONAL OFFICE, GANESHKHIND, PUNE-411007 August, 2017 ACKNOWLEGEMENT “REVAMPING THE NATIONAL SECURITY LAWS OF INDIA: NEED OF THE HOUR” is a non-doctrinal project, conducted to find out the actual implementation of the laws made for the national security. This Minor research project undertaken was indeed a difficult task but it was an endeavour to find out different dimensions in which the national security laws are implemented by the executive branch of the government. At such a juncture, it was necessary to rethink on this much litigated right. Our interest in this area has promoted us to undertake this venture. We are thankful to UGC for giving us this opportunity. We are also thankful Prof. Dr. Mukund Sarda, Dean and Principal for giving his valuable advices and guiding us. Our heartfelt gratitude to Dr. Ujwala Bendale for giving more insight about the subject. We are also thankful to Dr. Jyoti Dharm, Archana Ubhe & Vaibhav Bhagat for assisting us by formatting and typing the work. We are grateful to the faculty of New Law College, Pune for their support and the library staff for cooperating to fulfil this endeavour. We are indebted to our families respectively for their support throughout the completion of this project. Prof. Aman R. Mishra Principle Investigator i CONTENTS Sr No. PARTICULARS Page No. 1. CHAPTER- I 1 -24 INTRODUCTION 2. -

Breathing Life Into the Constitution

Breathing Life into the Constitution Human Rights Lawyering In India Arvind Narrain | Saumya Uma Alternative Law Forum Bengaluru Breathing Life into the Constitution Human Rights Lawyering In India Arvind Narrain | Saumya Uma Alternative Law Forum Bengaluru Breathing Life into the Constitution Human Rights Lawyering in India Arvind Narrain | Saumya Uma Edition: January 2017 Published by: Alternative Law Forum 122/4 Infantry Road, Bengaluru - 560001. Karnataka, India. Design by: Vinay C About the Authors: Arvind Narrain is a founding member of the Alternative Law Forum in Bangalore, a collective of lawyers who work on a critical practise of law. He has worked on human rights issues including mass crimes, communal conflict, LGBT rights and human rights history. Saumya Uma has 22 years’ experience as a lawyer, law researcher, writer, campaigner, trainer and activist on gender, law and human rights. Cover page images copied from multiple news articles. All copyrights acknowledged. Any part of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted as necessary. The authors only assert the right to be identified wtih the reproduced version. “I am not a religious person but the only sin I believe in is the sin of cynicism.” Parvez Imroz, Jammu and Kashmir Civil Society Coalition (JKCSS), on being told that nothing would change with respect to the human rights situation in Kashmir Dedication This book is dedicated to remembering the courageous work of human rights lawyers, Jalil Andrabi (1954-1996), Shahid Azmi (1977-2010), K. Balagopal (1952-2009), K.G. Kannabiran (1929-2010), Gobinda Mukhoty (1927-1995), T. Purushotham – (killed in 2000), Japa Lakshma Reddy (killed in 1992), P.A. -

Trade Marks Journal No: 1771 , 14/11/2016 Class 41

Trade Marks Journal No: 1771 , 14/11/2016 Class 41 1478864 14/08/2006 DOON PUBLIC SCHOOL trading as ;DOON PUBLIC SCHOOL B-2, PASCHIM VIHAR, N DELHI Address for service in India/Agents address: MR. MANOJ V. GEORGE, MR. ARUN MANI B-23 A, SAGAR APARTMENTS, 6, TILAK MARG NEW DELHI-110001 Used Since :01/04/1978 DELHI SERVICE OF IMPARTING EDUCATION THIS IS CONDITION OF REGISTRATION THAT BOTH/ALL LABELS SHALL BE USED TOGETHER..THIS IS SUBJECT TO FILING OF TM-16 TO AMEND THE GOODS/SERVICES FOR SALE/CONDUCT IN THE STATES OF.DELHI ONLY. 3707 Trade Marks Journal No: 1771 , 14/11/2016 Class 41 1807857 16/04/2009 MEDINEE INSTITUTE OF INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY SANTIPUR,MECHEDA,KOLAGHAT,PURBA MEDINIPUR,PIN 721137,W.B. SERVICE PROVIDER Address for service in India/Agents address: KOLKATA TRADE MARK SERVICE. 71, CANNING STREET (BAGREE MARKET) 5TH FLOOR, ROOM NO. C 524 KOLKATA 700 001,WEST BENGAL. Used Since :10/06/2006 KOLKATA EDUCATION, PROVIDING OF TRAINING, TEACHING, COACHING AND LEARNING OF COMPUTER, SPOKEN ENGLISH, CALL CENTER, PUBLIC SCHOOL. 3708 Trade Marks Journal No: 1771 , 14/11/2016 Class 41 1847931 06/08/2009 UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN SYDNEY GREAT WESTERN HIGHWAY, WERRINGTON, NEW SOUTH WALES, 2747, AUSTRALIA. SERVICE PROVIDERS. AN AUSTRALIAN UNIVERSITY. Address for service in India/Agents address: S. MAJUMDAR & CO. 5, HARISH MUKHERJEE ROAD, KOLKATA - 700 025, INDIA. Proposed to be Used KOLKATA EDUCATIONAL SERVICES, INCLUDING THE PROVISION OF SUCH SERVICES FROM A COMPUTER DATABASE OR THE INTERNET, THE CONDUCT OF EDUCATIONAL COURSES AND LECTURES, AND -

We Had Vide HO Circular 443/2015 Dated 07.09.2015 Communicated

1 CIRCULAR NO.: 513/2015 HUMAN RESOURCES WING I N D E X : STF : 23 INDUSTRIAL RELATIONS SECTION HEAD OFFICE : BANGALORE-560 002 D A T E : 21.10.2015 A H O N SUB: IBA MEDICAL INSURANCE SCHEME FOR RETIRED OFFICERS/ EMPLOYEES. ******* We had vide HO Circular 443/2015 dated 07.09.2015 communicated the salient features of IBA Medical Insurance Scheme for the Retired Officers/ Employees and called for the option from the eligible retirees. Further, the last date for submission of options was extended upto 20.10.2015 vide HO Circular 471/2015 dated 01.10.2015. The option received from the eligible retired employees with mode of exit as Superannuation, VRS, SVRS, at various HRM Sections of Circles have been consolidated and published in the Annexure. We request the eligible retired officers/ employees to check for their name if they have submitted the option in the list appended. In case their name is missing we request such retirees to take up with us by 26.10.2015 by sending a scan copy of such application to the following email ID : [email protected] Further, they can contact us on 080 22116923 for further information. We also observe that many retirees have not provided their email, mobile number. In this regard we request that since, the Insurance Company may require the contact details for future communication with the retirees, the said details have to be provided. In case the retirees are not having personal mobile number or email ID, they have to at least provide the mobile number or email IDs of their near relatives through whom they can receive the message/ communication. -

July Current Affairs 2021

www.gradeup.co Monthly Current Affairs July 2021 मासिक िम सामयिकी जुलाई 2021 Important News: State UNESCO’s ‘Historic Urban Landscape’ Project for Gwalior, Orchha launched Why in News • In Madhya Pradesh, Gwalior and Orchha cities have been selected by UNESCO under its ‘Historic Urban Landscape’ Project. Key Points • 6 cities of South Asia, including Ajmer and Varanasi in India are already involved in this project. Gwalior and Orchha have been included as the 7th and 8th cities. • The cities will be jointly developed by UNESCO, Government of India and Madhya Pradesh by focusing on their historical and cultural improvement. Note: • Gwalior was established in the 9th century and ruled by Gurjar Pratihar Rajvansh, Tomar, Baghel Kachvaho and Scindias. Gwalior is known for its temples and palaces. • Orchha is popular for its palaces and temples and was the capital of the Bundela kingdom in the 16th century. About Historic Urban Landscape (HUL) Project: • HUL Project was started in the year 2011, for the inclusive and well-planned development of fast-growing historical cities while preserving the culture and heritage. Source: newsonair Karnataka’ s new Chief Minister Basavaraj Bommai Why in News • Lingayat leader Basavaraj Bommai took oath as the new Chief Minister of Karnataka. Key Points • In the ceremony at the Glass House of the Karnataka Raj Bhavan in Bengaluru, Governor Thaawarchand Gehlot administered the oath of office and secrecy to Basavaraj Bommai. About Basavaraj Bommai: • Bommai is the son of former chief minister S R Bommai. • He is a two-time MLC and three-time MLA from Shiggaon in Haveri district in North Karnataka. -

C on T E N T S

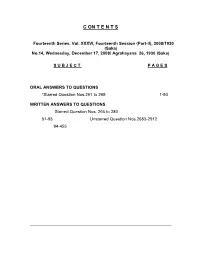

C ON T E N T S Fourteenth Series, Vol. XXXVI, Fourteenth Session (Part-II), 2008/1930 (Saka) No.14, Wednesday, December 17, 2008/ Agrahayana 26, 1930 (Saka) S U B J E C T P A G E S ORAL ANSWERS TO QUESTIONS *Starred Question Nos.261 to 265 1-50 WRITTEN ANSWERS TO QUESTIONS Starred Question Nos. 266 to 280 51-93 Unstarred Question Nos.2683-2912 94-455 * The sign + marked above the name of a Member indicates that the Question was actually asked on the floor of the House by that Member. PAPERS LAID ON THE TABLE 456-491 MESSAGES FROM RAJYA SABHA 492-493 ESTIMATES COMMITTEE 19th and 20th Reports 494 PUBLIC ACCOUNTS COMMITTEE 78th to 80th Reports 494 COMMITTEE ON PETITIONS 43rd to 45th Reports 495 STANDING COMMITTEE ON HUMAN RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT 212th Report 496 STATEMENT BY MINISTERS 497-508 (i) Status of implementation of the recommendations contained in the 70th Report of the Standing Committee on Finance on Demands for Grants (2008-09), pertaining to the Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation. Shri G.K. Vasan 497-499 (ii) Status of implementation of the recommendations contained in the 204th Report of the Standing Committee on Human Resource Development on Demands for Grants (2007-08), pertaining to the Ministry of Youth Affairs and Sports. Dr. M.S. Gill 500 (iii) Status of implementation of the (a) recommendations contained in the 23rd Report of the Standing Committee on Personnel, Public Grievances, Law and Justice on the Government's policy of appointment on compassionate ground, pertaining to the Ministry of Personnel, Public Grievances and Pensions (b) Status of implementation of the recommendations contained in the 189th Report of the Standing Committee on Science and Technology, Environment and Forests on Demands for Grants (2008-09), pertaining to the Department of Space. -

The Indian Police Journal the Indian Police Journal

The Indian Police Journal The Indian Police Journal The Indian Police Journal Nov - Dec, 2018 Editorial Board Contents Dr. A.P. Maheshwari, IPS 1. From the Chairman, Editorial Board ii DG, BPR&D Chairman 2. From the Director’s Desk vi Shri Sheel Vardhan Singh, IPS 3. Indian Police : The Sentinels of Peace vii Addl. Director, Intelligence Bureau 4. Prime Minister dedicates National Police Memorial to the Nation 2 Spl. Editor 5. Towards a More Secure Nation 6 Shri V.H. Deshmukh, IPS 6. Hot Springs: Saga of Heroism 14 ADG, BPR&D Member 7. The Story of Hot Springs 20 Shri Manoj Yadava, IPS 8. Honouring Our Martyrs : More than Cenotaphs are Needed 34 Addl. Director, Intelligence Bureau 9. A Pilgrimage to the Home of Brave 44 Member 10. Police Martyrs : A Statistical Study 50 Dr. Nirmal Kumar Azad, IPS IG (SPD), BPR&D 11. Life of Policemen 58 Member 12. Police Martyrdom: Through the Decades 62 Shri Sumit Chaturvedi, IPS 13. National Police Memorial Complex 74 Dy. Director Intelligence Bureau 14. A Memorial in Stone 76 Member 15. The Making of the Monument 86 Shri S.K. Upadhyay DIG (SPD) BPR&D 16. The National Police Museum : A Dream Come True 96 Member 17. Making the Last Man Stakeholder 102 Shri R.N. Meena Editor, BPR&D 18. From the Archives 106 From the Chairman, Editorial Board From a Policeman’s Heart Society which honours its heroes produces more heroes! he Martyr’s Memorial standing, proud and strong, at an altitude of 16000 Dr. A.P. Maheshwari, IPS '*%35 ' Tft. -

Infowars » Elements of an Inside Job in Mumbai Attacks » Print

Infowars » Elements of an Inside Job in Mumbai Attacks » Print http://www.infowars.com/elements-of-an-inside-job-in-mumbai-attacks/print - Infowars - http://www.infowars.com - Elements of an Inside Job in Mumbai Attacks Posted By aaron On December 21, 2008 @ 6:55 pm In Featured Stories,Old Infowars Posts Style | Comments Disabled Jeremy R. Hammond Foreign Policy Journal December 21, 2008 Indian police last week arrested Hassan Ali Khan, who was wanted for investigations into money laundering and other illicit activities, and who is also said to have ties to Dawood Ibrahim, the underworld kingpin who evidence indicates was the mastermind behind the terrorist attacks in Mumbai last month. Ibrahim is also alleged to have close ties with both Pakistan’s Inter-Service Intelligence (ISI) agency and the CIA. Another character linked to the CIA whose name is now beginning to figure into the web of connections between the Mumbai attacks, criminal organizations, and intelligence agencies is Saudi arms dealer Adnan Khashoggi, of Iran-Contra infamy. Khashoggi has been implicated in arms deals with drug traffickers and terrorist groups, including within India. Dawood Ibrahim is a known major drug trafficker whom India claims is being protected by Pakistan. As Foreign Policy Journal previously reported, there are also some indications that the CIA has a similar interest in preventing Ibrahim from being handed over to India. Ibrahim is wanted by India for the recent Mumbai attacks as well as for bombings that occurred there in 1993. 1 von 13 24/05/15 12:01 Infowars » Elements of an Inside Job in Mumbai Attacks » Print http://www.infowars.com/elements-of-an-inside-job-in-mumbai-attacks/print Ibrahim is a native of India who rose through the ranks of the criminal underworld in Bombay (now Mumbai). -

State of Maharashtra Vs. Fahim Harshad Mohammad Yusuf Ansari

Crl.A. No. 1961 of 2011 - State of Maharashtra Vs. Fahim Harshad Mohammad Yusuf Ansari ... http://www.keralaw.com/judgments/case-number/criminal-appeal/2011-1899/2011-1961 Research Home News Articles Statutes Realtime Judgments Subscribers Forum Head Notes Docs A Diary Archives Feedback Judgments > Case Number > Criminal Appeal > Crl.A. No. 1899 of 2011 - Mohammed Ajmal Mohammad Amir Kasab @ Abu Mujahid Vs. State of Maharashtra > 0 Crl.A. No. 1961 of 2011 - State of Maharashtra Vs. Fahim Harshad Mohammad Yusuf Ansari & Another Sale BONITA Onlineshop www.bonita.de Bis zu -50% auf Mode von BONITA. Bequem & sicher online bestellen! 1 of 53 26.7.2013 18:10 Crl.A. No. 1961 of 2011 - State of Maharashtra Vs. Fahim Harshad Mohammad Yusuf Ansari ... http://www.keralaw.com/judgments/case-number/criminal-appeal/2011-1899/2011-1961 IN THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA CRIMINAL APPELLATE JURISDICTION Aftab Alam and Chandramauli Kr. Prasad, JJ. August 29, 2012 CRIMINAL APPEAL NO.1961 OF 2011 2 of 53 26.7.2013 18:10 Crl.A. No. 1961 of 2011 - State of Maharashtra Vs. Fahim Harshad Mohammad Yusuf Ansari ... http://www.keralaw.com/judgments/case-number/criminal-appeal/2011-1899/2011-1961 STATE OF MAHARASHTRA … APPELLANT VERSUS FAHIM HARSHAD MOHAMMAD YUSUF ANSARI & ANOTHER … RESPONDENTS AND TRANSFER PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO.30 OF 2012 RADHAKANT YADAV … PETITIONER VERSUS UNION OF INDIA & OTHERS … RESPONDENTS Head Note:- Indian Evidence Act, 1872 - Sections 25 and 26 - Criminal Procedure Code, 1973 - Sections 164 and 366 - Explosive Substance Act, 1908 - Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, 1967 - Section 16 - Indian Penal Code, 1860 - Death Penalty - Conspiracy to wage war - Collecting arms - Criminal conspiracy to commit murder - Fairness of Trial - Right to an attorney - Right to remain silent 3 of 53 26.7.2013 18:10 Crl.A. -

Table of Contents INTERNATIONAL NEWS

www.toprankers.com Table of Contents INTERNATIONAL NEWS ........................................................................................ 3 NATIONAL NEWS .................................................................................................. 11 BANKING AND ECONOMICS ............................................................................... 36 AWARDS AND RECOGNITION ............................................................................. 39 SPORTS ................................................................................................................. 42 APPOINTMENTS AND RESIGNATIONS................................................................ 47 SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY ............................................................................. 49 OBITUARY ............................................................................................................ 51 SUMMITS AND MOU‟S ......................................................................................... 52 DAYS ..................................................................................................................... 54 1 www.toprankers.com 2 www.toprankers.com INTERNATIONAL - Hong Kong in recession as protests slam retailers, tourism On Thursday, the government said Hong Kong's economy shrank 3.2% in July-September from the previous quarter, pushing the city into a technical recession. -North Korea conducts new test of „super-large‟ rocket launcher: South Korea‘s military said Thursday that the North had launched two