The Power of One “I’Ve Taught My People to Live Again ...” Maoist Violence Is Not Prabhavati’S Way

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1. What Comprises Foreign Goods?

1. WHAT COMPRISES FOREIGN GOODS? A gentleman asks: “Should we boycott all foreign goods or only some select ones?” This question has been asked many times and I have answered it many times. And the question does not come from only one person. I face it at many places even during my tour. In my view, the only thing to be boycotted thoroughly and despite all hardships is foreign cloth, and that can and should be done through khadi alone. Boycott of all foreign things is neither possible nor proper. The difference between swadeshi and foreign cannot hold for all time, cannot hold even now in regard to all things. Even the swadeshi character of khadi is due to circumstances. Suppose there is flood in India and only one island remains on which a few persons alone survive and not a single tree stands; at such a time the swadeshi dharma of the marooned would be to wear what clothes are provided and eat what food is sent by generous people across the sea. This of course is an extreme instance. So it is for us to consider what our swadeshi dharma is. Today many things which we need for our sustenance and which are not imposed upon us come from abroad. As for example, some of the foreign medicines, pens, needles, useful tools, etc., etc. But those who wear khadi and consider it an honour or are not ashamed to have all other things of foreign make fail to understand the significance of khadi. The significance of khadi is that it is our dharma to use those things which can be or are easily made in our country and on which depends the livelihood of poor people; the boycott of such things and deliberate preference of foreign things is adharma. -

Authored by Dr. Rajeev Kishen

Authored by Dr. Rajeev Kishen. INDIA’S HEROES Anonymous Vocabulary and key words: 1. fidgeted 2. air of thrill and enthusiasm 3. assignment had not been a drudge 4. particular trait or quality 5. wish to emulate 6. crackle of sheets 7. rapt attention 8. perspiration 9. accustomed 10. not have a flair 11. two tenures 12. battalion in counter terrorism 13. insurgency 14. arranged for his evacuation 15. courageous 16. birds chirped 17. cars honked 18. abandon his responsibilities 19. restore the heritage structure 20. welled up 21. selfless 22. class rose as one, applauding and cheering 23. uphold the virtues of peace, tolerance and selflessness The story is narrated from the third person omniscient point of view. 1 INDIA’S HEROES Students Kabir Mrs. Baruah Students fidgeted and When Kabir got up to speak, his hands shook She gave them a few shifted in their seats, slightly and beads of perspiration appeared on seconds to settle and an air of thrill and his forehead. He was not accustomed to facing down, let us begin our enthusiasm prevailed. the entire class and speaking aloud. He knew he lesson for today. Mrs. She addressed an eager did not have a flair for making speeches. Baruah beamed Mrs. class 8 A. All forty However, he had worked hard on his Baruah said hands went up in assignments and written from the depth of his wonderful, you can unison. heart. His assignments were different from the speak on a profession A crackle of sheets was others. It did not focus on one person, profession someone you like and heard as students or quality. -

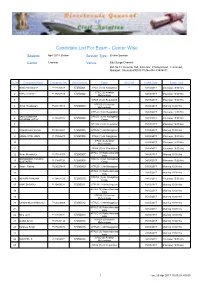

Admitted Candidates List

Candidate List For Exam - Center Wise Session: April 2017 Online Session Type: Online Session Center Chennai Venue: Edu Surge Chennai Old No 74, New No 165, 3rd Floor, Chettiyar Hall, TTK Road, Alwarpet, Chennai 600018 Ph No 044 43534811 Sr. No Candidate Name Computer No. Roll Number Paper Air Craft Exam Date Exam Time 1 Muthu Kumaran P P-11034378 17250001 CPLG (1) Air Navigation -- 03/05/2017 Afternoon 15:00 Hrs CPLG (2) Aviation 2 RITTU RAJAN P-17452315 -- 04/05/2017 Afternoon 15:00 Hrs 17250002 Meteorology 3 CPLG (3) Air Regulation -- 05/05/2017 Afternoon 15:00 Hrs ATPLG (2) Aviation 4 Vinod Sivadasan P-04018048 -- 05/05/2017 Morning 10:00 Hrs 17250003 Meteorology 5 ATPLG (4) Air Regulation -- 05/05/2017 Afternoon 15:00 Hrs SAAJVIGNESHA CPLCG (1) Air Navigation 6 P-12448585 -- 04/05/2017 Afternoon 15:00 Hrs JAYARAM JOTHY 17250004 Comp 7 CPLCG (2) Air Regulation -- 05/05/2017 Afternoon 15:00 Hrs 8 Chakshender Kumar P-09028923 17250005 ATPLG (1) Air Navigation -- 03/05/2017 Morning 10:00 Hrs 9 SANAL IYPE JOHN P-17452273 17250006 CPLG (1) Air Navigation -- 03/05/2017 Afternoon 15:00 Hrs CPLG (2) Aviation 10 -- 04/05/2017 Afternoon 15:00 Hrs Meteorology 11 CPLG (3) Air Regulation -- 05/05/2017 Afternoon 15:00 Hrs ATPLG (3) Radio Aids and 12 Dhruv Mendiratta P-07024203 -- 04/05/2017 Morning 10:00 Hrs 17250007 Insts MOHAMMED YASEEN CPLCG (1) Air Navigation 13 P-11447726 -- 04/05/2017 Afternoon 15:00 Hrs MUSTAFFA 17250008 Comp 14 Swati - Pahwa P-06023443 17250009 ATPLG (1) Air Navigation -- 03/05/2017 Morning 10:00 Hrs ATPLG (3) Radio Aids -

Role of the Women in National Movement in Bihar (1857-1947)

Parisheelan Vol.-XV, No.- 2, 2019, ISSN 0974 7222 628 Role of the Women in National during the tardy phase of movement, the women from Bihar hand charkhas and on the other hand when the movement gained momentum Movement in Bihar (1857-1947) they came forward as a flag-bearer. Inspired by brave women like Smt. C.C. Das, Smt. Prabhavati Devi, Smt. Urmilla devi, Rajvanshi Devi, Rajesh Kumar Prajwal* Kasturba Gandhi etc. the women of Bihar showed their inclination towards freedom movement. In this way, the women of Bihar gave significant contribution in different movements of freedom struggle like Abstract :-The women of Bihar have walked steps to steps in national non-cooperation movement boycotting Prince of Wales, Civil movement and also have been part of communist, socialist, trade union Disobedience Movement, organising large meeting in Ara against death and peasant movements. Overruling various social traditions and punishment of Bhagat Singh, Rajguru and Sukhdev, Individual Satyagraha stereotype mindset, the women of Bihar have stepped out during National and Quit India Movement etc. In this way, many brave women of Bihar movement. They have not only matched pace with men in the struggle defied the four walls to give full support to movement time to time and for freedom but also have provided successful leadership to it. Mahatma had been successful. They proved that women are not weak but they Gandhi employed Satyagraha for the first time in Champaran district of may fight for their motherland in need. Bihar in 1917 in order to protect people from the atrocities of Nilaha Key Word :National movement, Women, Bihar, Purdah system, Four Gora. -

Indian False Flag Operations

Center for Global & Strategic Studies Islamabad INDIAN FALSE FLAG OPERATIONS By Mr. Tauqir – Member Advisory Board CGSS Terminology and Genealogy The term false flag has been used symbolically and it denotes the purposeful misrepresentation of an actor’s objectives or associations. The lineage of this term is drawn from maritime affairs where ships raise a false flag to disguise themselves and hide their original identity and intent. In this milieu, the false flag was usually used by pirates to conceal themselves as civilian or merchant ships and to prevent their targets from escaping away or to stall them while preparing for a battle. In other cases, false flags of ships were raised to blame the attack on someone else. A false flag operation can be defined as follows: “A covert operation designed to deceive; the deception creates the appearance of a particular party, group, or nation being responsible for some activity, disguising the actual source of responsibility.” These operations are purposefully carried out to deceive public about the culprits and perpetrators. This phenomenon has become a normal practice in recent years as rulers often opt for this approach to justify their actions. It is also used for fabrication and fraudulently accuse or allege in order to rationalize the aggression. Similarly, it is a tool of coercion which is often used to provoke or justify a war against adversaries. In addition, false flag operations could be a single event or a series of deceptive incidents materializing a long-term strategy. A primary modern case of such operations was accusation on Iraqi President Saddam Hussain for possessing weapons of mass-destruction ‘WMD’, which were not found after NATO forces, waged a war on Iraq. -

Candidate List for Exam - Center Wise

Candidate List For Exam - Center Wise Session: April 2017 Regular Session Type: Regular Session Center Bangalore Sr. No Candidate Name Computer No. Roll Number Paper Air Craft Exam Date Exam Time 1 VIJAY KUMAR MISHRA P-17452203 03250001 CPLT (1) General -- 12/04/2017 Morning 10:00 Hrs 2 Dennis Almeida P-11034525 03250002 CPLT (1) General -- 12/04/2017 Morning 10:00 Hrs Diamond DA 42 3 CPLT (2) Specific 12/04/2017 Afternoon 15:00 Hrs Austro 4 RAHUL SUBRAMANIAN P-16451679 03250003 CPLT (1) General -- 12/04/2017 Morning 10:00 Hrs 5 AJIT BHATT P-16451451 03250004 CPLT (1) General -- 12/04/2017 Morning 10:00 Hrs Piper Seneca P A- 6 CPLT (2) Specific 12/04/2017 Afternoon 15:00 Hrs 34 7 John Avith Pereira P-06021425 03250005 CPLT (1) General -- 12/04/2017 Morning 10:00 Hrs 8 CPLT (2) Specific Cessna 152 A 12/04/2017 Afternoon 15:00 Hrs SITHAMBARAPILLAI 9 P-15450561 CPLT (1) General -- 12/04/2017 Morning 10:00 Hrs JAIGANESH 03250006 10 KAVYA R P-14449358 03250007 CPLT (2) Specific Cessna 152 A 12/04/2017 Afternoon 15:00 Hrs 11 SAURABH MALKHEDE P-15450248 03250008 CPLT (1) General -- 12/04/2017 Morning 10:00 Hrs 12 MANJUNATH SV P-16451566 03250009 CPLT (1) General -- 12/04/2017 Morning 10:00 Hrs 13 SHEROOK SHEMSU P-15450754 03250010 PPLT (1) General -- 12/04/2017 Morning 10:00 Hrs 14 PPLT (2) Specific Cessna 152 A 12/04/2017 Afternoon 15:00 Hrs 15 ARJUN NAIK P-14450061 03250011 PPLT (2) Specific Cessna 152 A 12/04/2017 Afternoon 15:00 Hrs 16 ANUJ KULSHRESHTHA P-16451376 03250012 PPLT (2) Specific Cessna 172 R 12/04/2017 Afternoon 15:00 Hrs SWAPNIL -

District Health Action Plan Siwan 2012 – 13

DISTRICT HEALTH ACTION PLAN SIWAN 2012 – 13 Name of the district : Siwanfloku Create PDF files without this message by purchasing novaPDF printer (http://www.novapdf.com) Foreword National Rural health Mission was launched in India in the year 2005 with the purpose of improving the health of children and mothers and reaching out to meet the health needs of the people in the hard to reach areas of the nation. National Rural Health Mission aims at strengthening the rural health infrastructures and to improve the delivery of health services. NRHM recognizes that until better health facilities reaches the last person of the society in the rural India, the social and economic development of the nation is not possible. The District Health Action Plan of Siwan district has been prepared keeping this vision in mind. The DHAP aims at improving the existing physical infrastructures, enabling access to better health services through hospitals equipped with modern medical facilities, and to deliver the health service with the help of dedicated and trained manpower. It focuses on the health care needs and requirements of rural people especially vulnerable groups such as women and children. The DHAP has been prepared keeping in mind the resources available in the district and challenges faced at the grass root level. The plan strives to bring about a synergy among the various components of the rural health sector. In the process the missing links in this comprehensive chain have been identified and the Plan will aid in addressing these concerns. The plan has attempts to bring about a convergence of various existing health programmes and also has tried to anticipate the health needs of the people in the forthcoming years. -

![6Rdevc Gz`]V TV Cvdfccvted Z =R \R](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1518/6rdevc-gz-v-tv-cvdfccvted-z-r-r-1481518.webp)

6Rdevc Gz`]V TV Cvdfccvted Z =R \R

+ , $ -"'. '.. SIDISrtVUU@IB!&!!"&#S@B9IV69P99I !%! %! ' !"#$ !/!/0 ,-. 1)-2 -$> 31145 &/ 01 & 0& 1 20 14 /) 1 41 4/4 & 0 0 ) 0 /0 ) 3 0 0 &6 /2 ) 2 0/ 341 ( )& 0/ 789 0 / 0 4 2 5 ) :; :9< = &$ - %& '( ) & **'*+!,- . !#* string of eight devastating Ablasts, including suicide attacks, struck churches and luxury hotels frequented by for- eigners in Sri Lanka on Easter Sunday, killing 215 people, including three Indians an American, and shattering a decade of peace in the island Their names are Lakshmi, nation since the end of the bru- Narayan Chandrashekhar and tal civil war with the LTTE. ondemning the “cold- Ramesh, Sushma said adding The blasts — one of the Cblooded and pre-planned details are being ascertained. deadliest attacks in the coun- barbaric acts” in Sri Lanka, Sushma tweeted, “I con- try’s history — targeted St Prime Minister Narendra veyed to the Foreign Minister Anthony’s Church in Colombo, Modi spoke to Sri Lankan of Sri Lanka that India is St Sebastian’s Church in the President Maithripala Sirisena ready to provide all humani- western coastal town of and Prime Minister Ranil tarian assistance. We are ready Negombo and Zion Church in Wickremesingh and offered to despatch medical teams.” the eastern town of Batticaloa the southern neighbour all Sushma said, “In all eight around 8.45 am (local time) as possible help and assistance to bomb blasts have taken place the Easter Sunday mass were in deal with the situation. — one more in a guest house progress, police spokesman “Strongly condemn the in Dehiwela near Colombo Ruwan Gunasekera said. horrific blasts in Sri Lanka. -

July Current Affairs 2021

www.gradeup.co Monthly Current Affairs July 2021 मासिक िम सामयिकी जुलाई 2021 Important News: State UNESCO’s ‘Historic Urban Landscape’ Project for Gwalior, Orchha launched Why in News • In Madhya Pradesh, Gwalior and Orchha cities have been selected by UNESCO under its ‘Historic Urban Landscape’ Project. Key Points • 6 cities of South Asia, including Ajmer and Varanasi in India are already involved in this project. Gwalior and Orchha have been included as the 7th and 8th cities. • The cities will be jointly developed by UNESCO, Government of India and Madhya Pradesh by focusing on their historical and cultural improvement. Note: • Gwalior was established in the 9th century and ruled by Gurjar Pratihar Rajvansh, Tomar, Baghel Kachvaho and Scindias. Gwalior is known for its temples and palaces. • Orchha is popular for its palaces and temples and was the capital of the Bundela kingdom in the 16th century. About Historic Urban Landscape (HUL) Project: • HUL Project was started in the year 2011, for the inclusive and well-planned development of fast-growing historical cities while preserving the culture and heritage. Source: newsonair Karnataka’ s new Chief Minister Basavaraj Bommai Why in News • Lingayat leader Basavaraj Bommai took oath as the new Chief Minister of Karnataka. Key Points • In the ceremony at the Glass House of the Karnataka Raj Bhavan in Bengaluru, Governor Thaawarchand Gehlot administered the oath of office and secrecy to Basavaraj Bommai. About Basavaraj Bommai: • Bommai is the son of former chief minister S R Bommai. • He is a two-time MLC and three-time MLA from Shiggaon in Haveri district in North Karnataka. -

![19?Stcwa^]Tb2^]Vatbbbfxuc[H](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0209/19-stcwa-tb2-vatbbbfxuc-h-1630209.webp)

19?Stcwa^]Tb2^]Vatbbbfxuc[H

C M Y K !!( RNI Regn. No. MPENG/2004/13703, Regd. No. L-2/BPLON/41/2006-2008 ,+!,% .;<= ) * ++ ,,- +. +32&-4!5 ! ""# " $" % # "# % % # " " " %" $ " ! "" # " % 6" 7 6 &' () ,, * &#+,-.'.&0 112&,.32 # 46 >=6>/.?@ .>A=.(B/ !"#$% $#$#$# !# &'" !" #$$ Chief Minister Mamata won from Wayanad with a Banerjee, who had emerged as record margin, but his humil- odi hai to mumkin hai. the most vocal critic of the iating defeat at the hands of MThe evocative tagline of Prime Minister during the poll Smriti Irani in the family pock- the BJP campaign aptly reflects campaign. All the seven phas- et borough of Amethi is the poverty next five-year. Taking the party’s massive victory in es of the polls were marred by cruelest blow the BJP has a dig at Left parties and their the Lok Sabha polls. The brand violence, and both the PM inflicted on the Congress chief. tating that the landslide alleged commitment to the ‘Modi’ has outshone every and BJP chief Amit Shah had The results show that in Srepeat mandate has sur- welfare of workers, he said the competitor, be it regional warned that those engaged in direct contest with the BJP, the prised the whole world and put BJP Government provided satraps or Congress president bloodletting will pay for it Congress has no chance to forward a “new narrative” for pension to 40 crore labourers Rahul Gandhi, who found few after the elections. Now, that survive. The two parties were India for waging a decisive bat- in the unorganised sector. takers for his “chowkidar chor the BJP stands neck and neck locked in direct contest on tle against poverty, Prime Even as Shah in his address hai” jibe at the PM. -

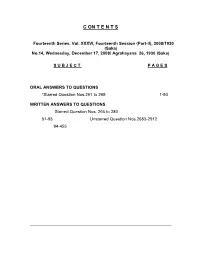

C on T E N T S

C ON T E N T S Fourteenth Series, Vol. XXXVI, Fourteenth Session (Part-II), 2008/1930 (Saka) No.14, Wednesday, December 17, 2008/ Agrahayana 26, 1930 (Saka) S U B J E C T P A G E S ORAL ANSWERS TO QUESTIONS *Starred Question Nos.261 to 265 1-50 WRITTEN ANSWERS TO QUESTIONS Starred Question Nos. 266 to 280 51-93 Unstarred Question Nos.2683-2912 94-455 * The sign + marked above the name of a Member indicates that the Question was actually asked on the floor of the House by that Member. PAPERS LAID ON THE TABLE 456-491 MESSAGES FROM RAJYA SABHA 492-493 ESTIMATES COMMITTEE 19th and 20th Reports 494 PUBLIC ACCOUNTS COMMITTEE 78th to 80th Reports 494 COMMITTEE ON PETITIONS 43rd to 45th Reports 495 STANDING COMMITTEE ON HUMAN RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT 212th Report 496 STATEMENT BY MINISTERS 497-508 (i) Status of implementation of the recommendations contained in the 70th Report of the Standing Committee on Finance on Demands for Grants (2008-09), pertaining to the Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation. Shri G.K. Vasan 497-499 (ii) Status of implementation of the recommendations contained in the 204th Report of the Standing Committee on Human Resource Development on Demands for Grants (2007-08), pertaining to the Ministry of Youth Affairs and Sports. Dr. M.S. Gill 500 (iii) Status of implementation of the (a) recommendations contained in the 23rd Report of the Standing Committee on Personnel, Public Grievances, Law and Justice on the Government's policy of appointment on compassionate ground, pertaining to the Ministry of Personnel, Public Grievances and Pensions (b) Status of implementation of the recommendations contained in the 189th Report of the Standing Committee on Science and Technology, Environment and Forests on Demands for Grants (2008-09), pertaining to the Department of Space. -

The Indian Police Journal the Indian Police Journal

The Indian Police Journal The Indian Police Journal The Indian Police Journal Nov - Dec, 2018 Editorial Board Contents Dr. A.P. Maheshwari, IPS 1. From the Chairman, Editorial Board ii DG, BPR&D Chairman 2. From the Director’s Desk vi Shri Sheel Vardhan Singh, IPS 3. Indian Police : The Sentinels of Peace vii Addl. Director, Intelligence Bureau 4. Prime Minister dedicates National Police Memorial to the Nation 2 Spl. Editor 5. Towards a More Secure Nation 6 Shri V.H. Deshmukh, IPS 6. Hot Springs: Saga of Heroism 14 ADG, BPR&D Member 7. The Story of Hot Springs 20 Shri Manoj Yadava, IPS 8. Honouring Our Martyrs : More than Cenotaphs are Needed 34 Addl. Director, Intelligence Bureau 9. A Pilgrimage to the Home of Brave 44 Member 10. Police Martyrs : A Statistical Study 50 Dr. Nirmal Kumar Azad, IPS IG (SPD), BPR&D 11. Life of Policemen 58 Member 12. Police Martyrdom: Through the Decades 62 Shri Sumit Chaturvedi, IPS 13. National Police Memorial Complex 74 Dy. Director Intelligence Bureau 14. A Memorial in Stone 76 Member 15. The Making of the Monument 86 Shri S.K. Upadhyay DIG (SPD) BPR&D 16. The National Police Museum : A Dream Come True 96 Member 17. Making the Last Man Stakeholder 102 Shri R.N. Meena Editor, BPR&D 18. From the Archives 106 From the Chairman, Editorial Board From a Policeman’s Heart Society which honours its heroes produces more heroes! he Martyr’s Memorial standing, proud and strong, at an altitude of 16000 Dr. A.P. Maheshwari, IPS '*%35 ' Tft.