Memorial Tribute to Roger J. Kiley Thomas L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Quasi- Crasmoritvrvs

ame DISCEQUASI-SEALER-VICTURVsVlVE- QUASI- CRASMORITVRVS VOL. LIV. NOTRE DAME, INDIANA, DECEMBER II, 1920. No. II. Notre Dame Football, 1920. battles to come. Wynne toted the oval across the enemy's, zero line for the first touchdown BY ALFRED N. SLAGGERT, 21. of the season, following several titanic advances by the battering backs of the first string.. Early AUDED from coast to coast by recog in the second quarter these same backs again nized critics as the greatest of the great . began to evidence greed for yardage, and Gipp,t lt.,~HS«^ in footballdom, Rockne's super-eleven hurtling through the Wolverine tacklers, struck of 1920 has just emerged from another a spectacular gallop for thirty yards to another season with nothing but victories to its credit. touchdown. Mohardt and Coughlin, who were Even the most conservative are forced to con substituted for Gipp and Barry, plunged time cede to this wonder eleven and-its peerless ' after time through the Kalamazoo wall and had mentor first place when ranking the country's advanced the ball to the opposition's four-yard best gridiron machines of this year. line when the half ended.. In the second half A bewildering aerial, attack, herculean line- there came a shower of touchdowns-r-by Barry, plunging, faultless team play, brilliancy in. both Brandy, Kasper, and Mohardt.. In.the last offensive and defensive play—these were some quarter Kalamazoo. failed miserably in its of the many merits shown consistently in the attempt to save itself via the air route from- games against Nebraska, the Army, Indiana, a zero defeat. -

High School's Coral Reef Staff Kept Busy Football On

f 0 Vol. V, No. 38 U. S. Naval Operating Base, Guantanamo Bay, Cuba Saturday, 11 November 1950 HIGH SCHOOL'S CORAL FOOTBALL ON AFRS DEADLINE FOR NROTC REEF STAFF KEPT BUSY PROGRAM EXTENDED WGBY, through the facilities of New York Shortwave Station Aiming at three hundred pledges, the By of the Armed Forces Radio Service, Authority of AlNav 122-50, the yearbook staff of NOB School is the deadline date for receipt of will broadcast the Ohio State- now busy with its annual sales cam- applications in BuPers of qualified paign here on the Base. The year- Wisconsin football game beginning 2:03 p.m. today with Al Helfer enlisted personnel for the NROTC book, appropriately named the program has been extended- to 18 "Coral Reef", promises to be the announcing. This game will be by a delayed broadcast of November. The extension was due biggest and best that the school followed to the Notre Dame-Pittsburgh game the small number of applications has ever published. For the first received by the date of the AlNav. time, the books will be solidly with Joe Boland behind the Mic- rophone. Football scores will be For those interested and who do bound in leatherette embossed not know of the NROTC program, covers. given at 6:15. (Complete roundup of scores will be in the Papoose it is outlined briefly below. An outstanding feature of the 1. Public Law 729, 79th Con- "Coral Reef" is the complete cover- Sunday). gress, approved 13 Sunday at 2:15 AFRS will air the August 1946 age given to all of the elementary instituted the selection and train- grades from Kindergarten up. -

Notre Dame Scholastic Football Review

ame DISCEQUASI-SEALER-VICTURVsVlVE- QUASI- CRASMORITVRVS VOL. LIV. NOTRE DAME, INDIANA, DECEMBER II, 1920. No. II. Notre Dame Football, 1920. battles to come. Wynne toted the oval across the enemy's, zero line for the first touchdown BY ALFRED N. SLAGGERT, 21. of the season, following several titanic advances by the battering backs of the first string.. Early AUDED from coast to coast by recog in the second quarter these same backs again nized critics as the greatest of the great . began to evidence greed for yardage, and Gipp,t lt.,~HS«^ in footballdom, Rockne's super-eleven hurtling through the Wolverine tacklers, struck of 1920 has just emerged from another a spectacular gallop for thirty yards to another season with nothing but victories to its credit. touchdown. Mohardt and Coughlin, who were Even the most conservative are forced to con substituted for Gipp and Barry, plunged time cede to this wonder eleven and-its peerless ' after time through the Kalamazoo wall and had mentor first place when ranking the country's advanced the ball to the opposition's four-yard best gridiron machines of this year. line when the half ended.. In the second half A bewildering aerial, attack, herculean line- there came a shower of touchdowns-r-by Barry, plunging, faultless team play, brilliancy in. both Brandy, Kasper, and Mohardt.. In.the last offensive and defensive play—these were some quarter Kalamazoo. failed miserably in its of the many merits shown consistently in the attempt to save itself via the air route from- games against Nebraska, the Army, Indiana, a zero defeat. -

Notre Dame Alumnus, Vol. 47, No. 05

The Archives of The University of Notre Dame 607 Hesburgh Library Notre Dame, IN 46556 574-631-6448 [email protected] Notre Dame Archives: Alumnus NOTRE DAME IMll JULY-AUGUST, 1969 Nonviolence or Nonexistence? The University Attempts an Answer VoL 47 No. 5 Joly-August 1969 James D. Cooney EXECUTIVE SEOIETAKV ALUMNI ASSOCIATION For your informatioii John P. Thurin '59 EonaK This is my first opportunity to welcome you to the magazine and it's a Tom Sulltvan '66 pleasure. You may notice some marked variations in both style and quality — MANACINO EDITOR hopefully pleasing — this time around, mainly because we've got a penchant Sandn Loiufoote for experimentation and because for the first time we were able to utilize the ASSISTANT EDITOB offset printing method to produce the ALUMNUS. We hope you have the Jeannine Doty EDITOUAL ASSISTANT patience to bear with us in our continuing search for that piece de resistence M. Bruce Harbn '49 in style. Though it may seem we've been a bit on the inconsistent side, we CHIEF PHOTOCKAFHEK feel each issue brings us closer to our objective. ALIJMNI ASSOCIATION OFTICERS This, our mid-summer effort, is devoted in large part to a feature on the Richaid A. Rosenthal '54 University's new program for the nonviolent resolution of human conflict. HONOHAItV FkESIDENT Leonard H. Skoglund '38 The program is a unique academic venture with implications that seem terribly niESniENT relevant in a society swollen with cruelty and violence. Prof. Charles Edwaid G. CantweU '24 McCarthy, the program director, sheds light on interesting aspects of the VlCE-BttSIDENT program and the problem with which it will be concerned. -

Heisman Trophy Winners Heisman Trophy Here’S a Year-By-Year Listing of Heisman Trophy Winners, Plus Notre Dame Players Who Placed in the Voting

NOTRE DAME WINNERS AWARD Chris Zorich was the 1990 winner of the Lombardi Award, which is annually presented to the top line- man in college football. Heisman Trophy Winners Heisman Trophy Here’s a year-by-year listing of Heisman Trophy winners, plus Notre Dame players who placed in the voting: 1935 Jay Berwanger, Chicago Bill Shakespeare (3rd) 1936 Larry Kelley, Yale None 1937 Clint Frank, Yale None 1938 Davey O’Brien, TCU Whitey Beinor (9th) 1939 Nile Kinnick, Iowa None 1940 Tom Harmon, Michigan None 1941 Bruce Smith, Minnesota Angelo Bertelli (2nd) 1942 Frank Sinkwich, Georgia Angelo Bertelli (6th) 1943 Angelo Bertelli, Notre Dame Creighton Miller (4th), Jim White (9th) 1944 Les Horvath, Ohio State Bob Kelly (6th) 1945 Doc Blanchard, Army Frank Dancewicz (6th) 1946 Glenn Davis, Army John Lujack (3rd) 1947 John Lujack, Notre Dame None 1948 Doak Walker, SMU None 1949 Leon Hart, Notre Dame Bob Williams (5th), Emil Sitko (8th) 1950 Vic Janowicz, Ohio State Bob Williams (6th) 1951 Dick Kazmaier, Princeton None 1952 Billy Vessels, Oklahoma John Lattner (5th) 1953 John Lattner, Notre Dame None 1954 Alan Ameche, Wisconsin Ralph Guglielmi (4th) 1955 Hopalong Cassady, Ohio State Paul Hornung (5th) 1956 Paul Hornung, Notre Dame None 1957 John David Crow, Texas A&M None 1958 Pete Dawkins, Army Nick Pietrosante (10th) The John W. Heisman Memorial Trophy Award is presented each year to the outstanding 1959 Bill Cannon, LSU Monty Stickles (9th) college football player by the Downtown Athletic Club of New York. 1960 Joe Bellino, Navy None First known as the D.A.C. -

Notre Dame Alumnus, Vol. 39, No. 05 -- November 1961

The Archives of The University of Notre Dame 607 Hesburgh Library Notre Dame, IN 46556 574-631-6448 [email protected] Notre Dame Archives: Alumnus RALLVLSONS iUI NOTRE DAME m ALUMNUS i '-1^^ ^J ' -J -t 'U?^ Ji-. VOLUME 39 NUMBER 5 NOVEMBER ' 1961 ALUMNI ASSOCIATION BOARD OF DIRECTORS Officers JOHN C. 0'CoKsoR,'3S...Jlonorary President Sditorial Comment WALTER L. FLEMIXG, JR., '40 President PAUL J. Cusn:.N-G,'31 Fund Vice-President JAMES J. B\-RNE,'43 Club Vice-President W. EDMUND SHEA, '23.-..Class Vice-President from your JAMES E. ARMSTRONG, '25 Executive Secretary Alumni Secretary Directors to 1962 JAMES J. BYRNE, '43 Byrne Plywood Co. Do you get the feeling that fund- $300 to $500, would hark back to Ute Roj'al Oak, Michigan raising is currently a grim and unre University's famous first Endowment C PAUL J. GUSHING, '31 lenting obsession in the Notre Dame Drive, which proved that the first mil Hydraulic Dredging Co. family picture? lion is not necessarily the hardest. Oakland, California Well, I am not about to tell you that WALTER L. FLEMING^ JR., '40 IV. "The John W. Cavanaugh Ora Fleming & Sons, Inc. it is not serious, not vital, and not P.O. Box 1291, Dallas, Texas unrelenting. But — torical Society." This group of donors W. EDMUND SHEA, '23 I think we ought to breathe a little of $100 to $300, would commemorate Third National Bank Bldg. in spite of it. The grocery bill is grim one of the most eloquent of Notre Dayton, Ohio and unrelenting. But it would be a sad Dame's Presidents, not by eloquence Directors to 1963 family tliat never enjoyed a meal be alone, but by their belief in the cor- MAURICE CARROLL^ '19 cause of it. -

Notre Dame Football Review

) 1 Ql~IMIMIMIMIMIMIMIMIMIIQJ]MMJMIMJMIMIMIMIM!MIM!MJM!M!M!IMIMJMIMIWJMIM I I Univer~'ity o/Notre Dame . j t:)· i f i. Football Review I I l t I i I :>--I ! I I 1 l ~- - 1920 ~ ~tmllr&!r&I®GTillf<R'irr&lirtllf&!irtlij'Kfitl\ilirtllirtli®G'Kilirtllirtl®lr&ti'R11irtllt&Jt>I1GTil®Milt<&l@l@i@ltl] 1 J j Dedication l t K. K. Rockne, Coach Walter Halas, Ass't.: Coach l' F ranll Coughlin, Captain I Edward Andersou Glen Carberr:y H eartle:y Anderson Paul Castner Norman Barr}) Daniel Coughlin Edward De Cree ]oseph Brand}) ]ames Doole}) George Gipp Arthur Garve:y Roger Kile:y Donald Grant Fred ericll Larson · David H a:yes John M ohardt H'arr:y M ehre Lawrence Shaw Robert Phelan Maurice Smith ~Villiam Voss Forrest Calion, Michael Kein. Barr}) Holton, Michael Kane, Eugene Kenned:y, Lesslie Logan, Leo Mixson, Eugene Oberst, George Pro/lop, Michael Se:yfril, William Shea, F ranll Thomas, ] ames Wilcox I Contents The Schedule and Conches (A Review of the Gan1es) The Varsity The Freslnnen Inter-Hall Choice Chips The Olyn1pics Our Captains Press Connnent { Tu :E .Scii:EDULE ·Itt 1 ·Ill AND. COACiiES 1 l TWO UNDEFEATED YEARS N.D. 1919 N.D. 1920 14 Kalmnazoo 0 39 Kalmnazoo o. 60 :Mount Union 0 ·o t 41 \Vestern Stales 1 V1 Nebraska 9 16 Nebraska 7 i 53 · \Vestern State 9 28 Valparaiso 3 I 16 Indiana U. 3 27 Arn1y 17 f 12 \Vest Point 9 28 Purdue 0 i 13 lVIichigan Aggies 0 13 ·Indiana 10 1 33 ·Purdue 13 33 N ortlnves tern 7 I C)- l 14 l\'Iorningsidc 6 -t> l\'lichigan Aggies 0 l 229 Total 49 250 Total t.¥1 I In 1919 he carried the temn through lI an undefeated season of nin·e gmnes and .1 ·this year he has repeated. -

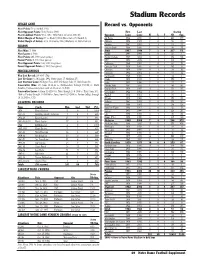

Stadium Records SINGLE GAME Record Vs

Stadium Records SINGLE GAME Record vs. Opponents Most Points: 73 vs. Haskell, 1932 Most Opponent Points: 51 by Purdue, 1960 First Last Scoring Most Combined Points: 90 vs. SMU, 1986 (Notre Dame 61, SMU 29) Opponent Game Game W L T ND Opp. Widest Margin of Victory: 73 vs. Haskell, 1932 (Notre Dame 73, Haskell 0) Air Force 1964 2000 10 3 0 423 199 Widest Margin of Defeat: 40 vs. Oklahoma, 1956 (Oklahoma 40, Notre Dame 0) Alabama 1976 1987 2 0 0 58 24 Arizona 1941 1982 1 1 0 51 23 SEASON Arizona State 1999 1999 1 0 0 48 17 Most Wins: 7, 1988 Army 1947 1998 7 1 0 237 61 Most Losses: 4, 1960 Baylor 1998 1998 1 0 0 27 3 Most Points: 260, 1988 (seven games) Boston College 1987 2004 5 4 0 284 188 Fewest Points: 0, 1933 (four games) BYU 1992 2005 3 1 0 138 74 Most Opponent Points: 168, 2003 (six games) California 1960 1967 2 0 0 62 15 Fewest Opponent Points: 0, 1932 (four games) Carnegie Tech 1930 1940 6 0 0 165 13 MISCELLANEOUS Clemson 1979 1979 0 1 0 10 16 Colorado 1984 1984 1 0 0 55 14 Won-Lost Record: 291-89-5 (.762) Dartmouth 1945 1945 1 0 0 34 0 Last Tie Game: vs. Michigan, 1992 (Notre Dame 17, Michigan 17) Drake 1930 1937 4 0 0 174 7 Last Overtime Game: Michigan State, 2005 (Michigan State 44, Notre Dame 41) Duke 1958 1966 2 0 0 73 7 Consecutive Wins: 28 (from 11-21-42 vs. -

Notre Dame Scholastic, Vol. 68, No. 05 -- 19 October 1934

The Notre Dame Scholastic Entered as second-class matter at Notre Dame, Indiana. Acceptance for mailingi tat special rate of postage. Section H03, October 3. 1917. Authorized June 25, 1D18.J VOLUME LXVIII OCTOBER 19,1934 No. 5 JAMES J. FHELAN DIES EDWARD J. VAN HUISSELING IS MADE AT BROOKIINE ROME NEW LEADER OF PRESIDENTS COUNCIL James J. Phelan, Laetare Medalist, lay trustee of the University, promi nent philanthropist, Boston banker, Boyle's Script Baffles and the head of many national and Would-Be Student Campus ELECTED LAST SUNDAY religious charities, died, at his home Radio Station Announcers By Paul Foley Aspiring announcers, crooners, so Making good their promise to elimi pranos, and other hopefuls giggled, nate politics from the organization, sputtered, and chuckled their way the Presidents' Council at their meet ing Sunday morning, elected Edward through the first of a series of radio J. Van Huisseling, of Elmhurst, 111., auditions in the Engineei'ing building, to the presidency of the Council. Wednesday evening, Oct. 10. Van Huisseling, who is president The Rev. Eugene P. Burke, C.S.C, of the Press Club, is a senior in the and Mr. Bob Kennett of WSBT, who were in charge of the auditions, an nounced that further tryouts will be held tonight at 8 o'clock in the En gineering building. The auditions last week were "screamingly" funny, with most of the screaming resulting not from the patter of the gag men but from the incidentals of the occasion—collaps ing chairs, giggling spectators, bursts of raucous laughter and "I-can't-pro- nounce-that-word" announcers. -

Notre Dame Football Review

......--------------------------c---------- \. Trusses, Beams, Lintels, Reinforcing Monorail Systems, Acetylene Welding Rods, Fire Escapes, Grills and Cutting and: Miscellaneous Tanks and Cranes Steel Work LUPTON STEEL SASH LUPTON STEEL BINS EDWARDS IRON WORKS Structural Steel and Iron SOUTH BEND~ INDIANA, US. A. 2025 South Main Street Phone Lincoln 741 7 Pictures in this For Your Toasted Sandwiches and W d'ffl~s stop at the Review are by . \ . - Elmore, News- FAMOUS 'WAFFLE and TOASTED SAND Times staff · WICH SHOP .· .. photographer. 213 N. Main St. South Bend Story of the Lombard game by Bert V. Dunne, ( Notre Our force is 100% with N.D.· Actiuites Dame student) who handles Shoe RepairinQ, Hat Cl~aninQ, all Notre Dame sports for Shoe ShininQ . · · Special Stand for Women ·.The Reasonable Pi-ices Exceptional Work Washington Shoe Repair Co. News~Times and .Boston Hatters 116 West Washington Avenuo · - . '~When Notre·Dame goes· marching .down· the field'' · Just watch the jaunty jerseys the players wear. All·a_re manu· lactured and guaran· teed by O'Shea Knitting Mills D. C. O'Shea, Pres. · W. C. Kin~, Sec'y. J. B. O'Shea, Vice-Pres. Makers Athletic Knitted Wear for Every Sport 2414_ No_rth Sacramento Avenue CHICAGO, ILLINOIS PHONE ALBANY 5011 OFFICIAL 1925 Football Review University· of Notre Dame I i Editors FRANCIS E. CODY JOHN A. PURCELL FRANK J. MASTERSON CONTRIBUTORS K. K. Rockne Wm. E. Carter Georqe Schill Andlj Slciqh Clem Crowe · Jerrlj Haljes Jas. Crusinbern; Dick Novak Jos. McNamara W. W. Brown R. Wentworth . Wm. f?oolerj Harrlj Elmore THR'EE REASONS--- why it is a safe investment of reliability· that you should give us ihat printing order l. -

Ohio Tiger Trap

The Professional Football Researchers Association Birth and Rebirth 1922 By PFRA Research 1922 saw the Chicago Bears born and George Halas win Nevertheless, George and Dutch believed there was a his first league championship -- though not the one for '22. future in professional football. The resuscitated Canton Bulldogs took that, largely because the Bears came into being. A league franchise But technically they didn't have a team. Starchmaker Staley was granted to a town that had no football field, and was through with pro football -- except for the lifetime pass several were granted to cities that had no teams. The Halas eventually gave him -- and the Staley franchise Green Bay Packers were reborn after they'd been would lapse when the required fees were not posted with assassinated by a couple of obscure towns in Illinois. the league. It was a year when money talked -- loudly at the league In the meantime, it became critical that George and Dutch meetings but softly to the press. It was a year when players secure their own franchise in Chicago for 1922. Chic gained ground on the field and lost ground to the owners. It Harley's brother Bill, a veteran Chicago promoter, applied was a year of great moral outrage and sharp practices. to the league for a Windy City franchise. Halas and Sternaman immediately asked for one of their own to It was also the first year that the National Football League replace the Staleys. actually called itself that. In 1920 and 1921, it went by the awkward and -- by 1922 -- misleading title of American Having been on the scene since 1920, the former Staley Professional Football Association, misleading because the leaders had the inside track. -

VOL 0044 ISSUE 0006.Pdf

The Archives of The University of Notre Dame 607 Hesburgh Library Notre Dame, IN 46556 574-631-6448 [email protected] Notre Dame Archives: Alumnus Compendium UNIVERSITY National Players from Rev. Mark J. Fitzgerald CENTER FOR Catholic U, "The Merchant CSC '28, prof, econ., "The CONTINUING CALENDAR of Venice", Jan. 13 and Common Market's Labor Dec 16-Ian. 3. Christmas "The Bu-ds". Jan. 14, Wash Problems," Nov., UND EDUCATION Vacation. ington Hall. Press. Donforth Regional Conf., Ion. 18. Last Class Do; of "The Playboy of the West- Dec. 1-4. Semester. John V. Hinkel '29, "Arling em World". ND-SMC The Fifth ND Cont on Popula Ian. 19 & 20, Study Days. ton: Monument to Heroes," atre, Washington Hall, tion, "The Role of the Ian. 2I-2S, Final Exams. a study of the national 8:30 pin, Feb. 2-4 and 9-11. Family in the Population Ian. 26-30, Semester Brealc shrine and of the men Symphony strings, Feb. 9 Explosion", Dec. 1-3. Ian. 30, Registration. buried there, Prentice-Hall, and 14. Resources Conservation Ian. 31, Second Semester $3.95. Marilyn Mason and Paul Conf., "Sharing the Costs Begins. Doctor, Organ and Viola Paul I. McCarthy '50. "Al of Water and Air Pollution Feb. 22, Senior Class Concert, Sacred Heart gebraic Extensions of Control," sponsored by the Washington Day Exer Church, Feb. 7. Fields," a text designed for Depts. of Econ. and Civil cises ond "Patriot of the Hev. Patrick Moloney CSC, use in graduate study of Eng., Dec. 9. Year" Aword. tenor, concert, Feb. 16. the theory of fields, Blais- Shelley Grushldn Trio, International Markets Conf.* dell Pub.