Perspective in Garden Design

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Garden to Landscape: Jean-Marie Morel and the Transformation of Garden Design Author(S): Joseph Disponzio Source: AA Files, No

From Garden to Landscape: Jean-Marie Morel and the Transformation of Garden Design Author(s): Joseph Disponzio Source: AA Files, No. 44 (Autumn 2001), pp. 6-20 Published by: Architectural Association School of Architecture Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/29544230 Accessed: 25-08-2014 19:53 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Architectural Association School of Architecture is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to AA Files. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 128.103.149.52 on Mon, 25 Aug 2014 19:53:16 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions From to Garden Landscape Jean-Marie Morel and the Transformation of Garden Design JosephDisponzio When the French landscape designer Jean-Marie Morel died on claim to the new style. Franc, ois de Paule Latapie, a protege of 7 October, 1810, the Journal de Lyon et du Departement du Rhone Montesquieu, was first to raise the issue in his translation of gave his obituary pride of place on the front page of its Thomas Whately's Observations onModern Gardening (1770), the ii October issue. It began simply: 'Jean-Marie Morel, architecte first theoretical text on picturesque gardening. -

Catalogue-Garden.Pdf

GARDEN TOURS Our Garden Tours are designed by an American garden designer who has been practicing in Italy for almost 15 years. Since these itineraries can be organized either for independent travelers or for groups , and they can also be customized to best meet the client's requirements , prices are on request . Tuscany Garden Tour Day 1 Florence Arrival in Florence airport and private transfer to the 4 star hotel in the historic centre of Florence. Dinner in a renowned restaurant in the historic centre. Day 2 Gardens in Florence In the morning meeting with the guide at the hotel and transfer by bus to our first Garden Villa Medici di Castello .The Castello garden commissioned by Cosimo I de' Medici in 1535, is one of the most magnificent and symbolic of the Medici Villas The garden, with its grottoes, sculptures and water features is meant to be an homage to the good and fair governing of the Medici from the Arno to the Apennines. The many statues, commissioned from famous artists of the time and the numerous citrus trees in pots adorn this garden beautifully. Then we will visit Villa Medici di Petraia. The gardens of Villa Petraia have changed quite significantly since they were commissioned by Ferdinando de' Medici in 1568. The original terraces have remained but many of the beds have been redesigned through the ages creating a more gentle and colorful style. Behind the villa we find the park which is a perfect example of Mittle European landscape design. Time at leisure for lunch, in the afternoon we will visit Giardino di Boboli If one had time to see only one garden in Florence, this should be it. -

French & Italian Gardens

Discover glorious spring peonies French & Italian Gardens PARC MONCEAu – PARIS A pyramid is one of the many architectural set pieces and fragments that lie strewn around the Parc Monceau in Paris. They were designed to bring together the landscape and transform it into an illusory landscape by designer Louis Carmontelle who was a dramatist, illustrator and garden designer. Tombs, broken columns, an obelisk, an antique colonnade and ancient arches were all erected in 1769 for Duc de’Orleans. PARC DE BAGAtelle – PARIS The Parc de Bagatelle is a full scale picturesque landscape complete with lakes, waterfalls, Palladian or Chinese bridges and countless follies. It’s one of Paris’ best loved parks, though it’s most famous for its rose garden, created in 1905 by JCN Forestier. The very first incarnation of Bagatelle in 1777 was the result of a famous bet between Marie-Antoinette and her brother-in-law, the comte d’Artois, whom she challenged to create a garden in just two months. The Count employed 900 workmen day and night to win the wager. The architect Francois-Joseph Belanger rose to the challenge, but once the bet was won, Thomas Blaikie, a young Scotsman, was brought on board to deliver a large English-style landscape. A very successful designer, Blaikie worked in France for most of his life and collaborated on large projects such as the Parc Monceau. JARDIN DU LUXEMBOURG – PARIS Please note this garden is not included in sightseeing but can be visited in free time. The garden was made for the Italian Queen Marie (de Medici), widow of Henry IV of France and regent for her son Louis XIII. -

Gardens of Genoa, the Italian Riviera & Florence

American Horticultural Society Travel Study Program GARDENS OF GENOA, THE ITALIAN RIVIERA & FLORENCE September 5 – 14, 2017 WITH AHS HOST KATY MOSS WARNER AND TOUR LEADER SUSIE ORSO OF SPECIALTOURS American Horticultural Society Announcing an 7931 East Boulevard Drive Alexandria, VA 22308 American Horticultural www.ahsgardening.org/travel Society Travel Study Program GARDENS OF GENOA, THE ITALIAN RIVIERA & FLORENCE September 5 – 14, 2017 WITH AHS HOST KATY MOSS WARNER AND TOUR LEADER SUSIE ORSO OF SPECIALTOURS Designed with the connoisseur of garden travel in mind, GARDENS OF GENOA, THE ITALIAN RIVIERA & FLORENCE the American Horticultural Society Travel Study Program Join us for unforgettable experiences including: offers exceptional itineraries that include many exclusive • Boboli Gardens, created by Cosimo I de’ Medici experiences and unique insights. Your participation benefits the work of the American Horticultural Society • Museum of the Park – the International Centre and furthers our vision of “Making America a Nation of of Open-Air Sculpture, an open air “botanical art Gardeners, a Land of Gardens.” gallery” • Uffizi Gallery, with work by masters including Botticelli, Michelangelo, da Vinci and Raphael • Villa Gamberaia and many other villas and palaces with wonderfully designed and tended gardens • The Italian city of Genoa, with its restored waterfront; Santa Margherita and Portofino, with their colorful charm; and Florence, the beloved Renaissance city Look inside for more details about this remarkable program… Please refer to the enclosed reservation form for pricing and instructions to reserve your place on this AHS Travel Study Program tour. For more information about AHS Travel Study Program tours, please contact development@ahsgardening. -

Landscape Design Professional

Choosing a Landscape Design Professional David Berle Extension Specialist he landscape is a very important aspect of a home. and licensing laws that regulate what a garden designer can T Having a beautiful, creative and functional landscape be called (title laws) and under what situations they can requires some understanding of design principles, plant design landscapes (practice laws). The terms can be materials and outdoor structural elements. A landscape confusing. installation can be very simple or extremely complicated. A landscape architect in Georgia, has received a Designing irrigation systems, outdoor lighting, stone walls college degree from an accredited university, worked for a and patios requires skills that go beyond the average time under another registered landscape architect, and homeowner. When the job seems too big an undertaking, passed a registration exam. This individual has received it may be time to call in a professional. This fact sheet basic training in engineering, construction, plant materials provides guidelines and suggestions for finding a garden and basic design. Depending on experience and personal designer. interest, this person may or may not have extensive knowledge of plants or residential design. In addition, a Why Hire a Garden Designer? registered landscape architect is trained to handle engineering problems and may even have considerable Some people find it rewarding to design and install a architectural knowledge, which could come in handy when landscape project themselves. Others prefer to have designing decks or patios. The fees for the services of a everything done by professionals. Professional people who registered landscape architect are typically higher than for turn these dreams into reality are garden designers, most other design professionals. -

Contemporary Trends in Landscape Design See Page 1

LNewsletteret of the ’s San DiegoT Horticulturalalk Society Plants!October 2013, Number 229 Contemporary Trends in Landscape Design SEE PAGE 1 OUR SPRING GARDEN TOUR page 2 HOLIDAY MARKETPLACE pages 3 & 7 FIRE RESIstANT SUCCULENTS page 5 SDHS WATERWISE GARDEN PARTY OUR page 6 TH D RIP IRRIGATION WORKSHOPS page 8 9 20 YEAR! CHANGES ON thE BOARD page 10 On the Cover: Contemporary garden featuring succulents TOW moRE moDERN GARDENS These very contemporary gardens were designed by two of our panelists for the October meeting. Kate Weisman's garden is below and Ryan Prange's is on the right. Kendra Berger's design is on the front cover. Get great ideas from these experts on October 14th. ▼SDHS SPONSOR GREEN THUMB SUPER GARDEN CENTERS 1019 W. San Marcos Blvd. • 760-744-3822 (Off the 78 Frwy. near Via Vera Cruz) • CALIFORNIA NURSERY PROFESSIONALS ON STAFF • HOME OF THE NURSERY EXPERTS • GROWER DIRECT www.supergarden.com Now on Facebook WITH THIS VALUABLE Coupon $10 00 OFF Any Purchase of $6000 or More! • Must present printed coupon to cashier at time of purchase • Not valid with any sale items or with other coupons or offers • Offer does not include Sod, Gift Certifi cates, or Department 56 • Not valid with previous purchases • Limit 1 coupon per household • Coupon expires 10/31/2013 at 6 p.m. San Diego Horticultural Society In This Issue... Our Mission is to promote the enjoyment, art, knowledge 2 2014 Spring Garden Tour and public awareness of horticulture in the San Diego area, 2 Important Member Information while providing the opportunity for education and research. -

Private Gardens to Please the Senses

AUGUST-SEPTEMBER 2016 On the 5 12 22 PRIVATE GARDENS TO TABLE OF CONTENTS: PLEASE THE SENSES Tips for a Great Visit in Atlanta . 2 BY KATE COPSEY President’s Message . 3 Executive Director’s Message . 4 n the last few issues GWA 2016 Honorees . 4 of On the QT, we Upcoming Events . 4 have been enticing Photography Column . 5 you to come to the Quick Conversations with Two . 6 GWA Atlanta Confer- Keynote Speakers ence & Expo with Get the Most Out of Your Conference . 8 Iscenes from the diverse Post Conference Tour Heads to Athens . 9 public gardens. Attendees will also Food Column . 10 enjoy seeing private gardens; we Get Your Videos Seen and Made . 11 Sustainability Column . 12 have an amazing variety scheduled. Regional News . 14 Some are designed professionally, Region Events . 16 but only one has full time staff to Business Column . 17 maintain the gardens. Gardeners New & Noteworthy . 18 who enjoy buying fun, new plants New Members . 20 and then finding somewhere to put Hot Off the Press . 21 them maintain other places. Writing Column . .22 Meet Stephanie Cohen . 23 BLANK GARDEN Silver Medal Media Awards . 24 On the high end is the Protect Your Online Privacy . 25 stunning estate of Arthur Blank, Meet James Baggett . 26 co-founder of The Home Depot, GWA Foundation . 27 which has its corporate head- Obituaries . 28 quarters in Atlanta. This property has terraced lawns that spread • • • Can’t log into the website? Visit MyGWA out from the home. These are under Member Resources. A login screen surrounded by shrubs, which give will appear. -

Landscape Design Workbook

Landscape Design Workbook Contents Introduction to Landscape Design .......................................................................................... 2 Role of Professionals ............................................................................................................. 2 Design Process....................................................................................................................... 3 Sample Garden ...................................................................................................................... 4 Things to Include in the Sketch Plan and Site Survey ............................................................... 7 Include notes on the following ........................................................................................................7 Sketch Plan ............................................................................................................................ 8 Site Survey ............................................................................................................................ 9 Shade at 9:00 a.m. ............................................................................................................... 10 Shade at 1:00 p.m. ............................................................................................................... 11 Shade at 6:00 p.m. ............................................................................................................... 12 Questionnaire to Help Determine Needs ............................................................................. -

GARDEN LOCALLY WINTER SYMPOSIUM 52Nd CVNLA SHORT COURSE and PESTICIDE RECERTIFICATION FEBRUARY 10, 11, 12, 2021

SEEK GLOBAL INSPIRATION; GARDEN LOCALLY WINTER SYMPOSIUM 52nd CVNLA SHORT COURSE AND PESTICIDE RECERTIFICATION FEBRUARY 10, 11, 12, 2021 WEDNESDAY, FEBRUARY 10 8:30 AM ZOOM WEBINAR OPENS 9 AM WELCOME, INTRODUCTIONS 9:05 AM READING DYNAMIC LANDSCAPES Rick Darke, Rick Darke LLC, Landscape Ethics, Photography, and Contextual Design Local and global trends in ecological stewardship are inspiring designs that embrace dynamic plant and animal communities. Because such landscapes are constantly in flux, their creation and care require enhanced skill in observation, analysis and strategy. This presentation illustrates how to enhance your ability to read into pre-existing and ongoing dynamics in a wide range of landscapes including residential gardens, parks, preserves and highly disturbed urban sites. The focus will be on the regenerative qualities of dynamic relationships and the resiliency that results from celebrating the inevitability of change. 10:05 AM BREAK 10:10 AM THE EVOLUTION OF A NEW RESILIENCE DESIGNER Larry Weaner, Weaner Landscape Design For more than 30 years, Larry Weaner has been a leader in creating resilient landscapes incorporating native plants. He chronicles his own journey and revelations about designing with native plants and his evolving understanding about how to work with the natural forces of the plant world to create native-friendly, resilient and beautiful landscapes. 11:10 AM BREAK 11:20 AM ADVENTURES IN EDEN: TALES OF GARDEN MAKING IN EUROPE TODAY Carolyn Mullet, author and garden designer We live in a time of great energy in garden making—private spaces that express ideas about beauty, place, nature, wildness, and sometimes fantasy. In this talk, Carolyn Mullet draws on her recent book Adventures in Eden, exploring through images the stories behind personal havens scattered across Europe that she chose not for their pedigree but for their owner’s passion and creativity. -

Groundcovers for the Garden Designer

Groundcovers for the Garden Designer Gary L. Koll er An eclectic selection of unusual plants for innovative gardeners. With one foot firmly planted in the living col- lections of the Arnold Arboretum and the other in the Landscape Architecture Depart- ment of the Harvard Graduate School of Design, I look at plants for novel uses that may not be fully appreciated by the garden- ing public. I have long believed that the cohe- siveness of a well-crafted garden relies heavily on the successful application of groundcovers. These plants can be used as a "substrate" through which other plants emerge, and which knits the planting into a composition that is visually and spatially pleasing. Given time and the appropriate conditions for growth, groundcovers potentially can reduce the maintenance requirements of the total landscape. Having the opportunity to visit many plant collections as well as developed gardens, I have come across a number of plants that appear to have all the qualities of a successful ground- cover, but are seldom cultivated as such. What are those qualities, you might well ask? Most good groundcovers are little more than very successful weeds controlled and put to good use. The plants not only must maintain them- Epimedium pmnatum var. colchicum in bloom. From in are selves the spot where they planted but the Arnold Arboretum Archives. also must be able to spread outward and colonize an ever-expanding area. With many good groundcovers, the primary concern is not of most volunteer weeds, and tough enough to encourage their growth, but rather to con- to survive neglect, poor soils, and extremes of tain them by installing restraining devices at drought and cold. -

Container Garden Designer Job Type

Posting Contact: Leigh McGonagle, [email protected] Job Description: Container Garden Designer Job Type: Full Time or Part Time, Seasonal Poplar Point Studio is the premier horticulture and fine gardening service in the Finger Lakes Area. We are focused on making great gardening accessible – offering services from regular garden maintenance, garden coaching, plant design & selection, garden installations, annual & container plantings, holiday décor and garden workshops. Working here means more than being part of a team – it is a family. We care deeply about our customers as well as those that we work with – directly on the team, or indirectly with vendors and suppliers. We are passionate about sharing our knowledge of horticultural practices, and strive for continuous learning in everything we do. At the core of PPS are driven horticulturists, creative problem solvers, and conscientious land stewards who are dedicated to providing expert green industry services. Our gardeners are constantly creating, maintaining, and sustaining gardens for clients who truly appreciate our professional level of artistry. Given the fast pace, and competitive environment, one must be able to take direction well, while maintaining a deep desire to think independently, creatively solve problems on the run, and be the eyes and ears of the garden. The ideal candidate for the Container Garden Designer would be someone who: - Has a passion for plants & working outdoors - Likes to have fun in life and has a positive attitude - Cares about serving others, -

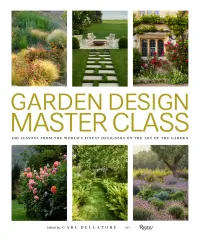

GARDEN DESIGN MASTER CLASS Have a Beauty Through All These Stages, to Have Am Curious to See How It Has Matured

Cyan Magenta Yellow Black Time MARGARET BROWER Gardens are always a work in progress. listen, rest and rejuvenate, meditate or play. Because the very essence of the garden is life, There will be a special place to feel the there is no way to avoid the progression of warmth of the sun or the cool of the shade, time. A garden is alive, moving through the the perfect spot for a lunch or dinner party, years along with the lives we live. Therefore, the place to escape to with a good book or for the element of time is a very important a nap. We add more plants, replace others. consideration for every garden design. We consider new areas to fill and plan for I begin in the past. What, if anything, additions in the coming years. is already growing in this place that can be This leads us to think about the future. included in a new plan? What past memories of Which trees do we plant for our children or childhood gardens might inform an affinity for grandchildren? We may never see some grow certain plants? What dreams have been held for to maturity, but those following us will. How the garden’s elements, structures, or purposes? will a hedge look in three to five years? How Moving to the present, I make a quick will the shade, sun, and climate change in this assessment of the space. This is the time to ask space? As the garden marks time through the questions and make initial suggestions. Then seasons, plants thrive and die, outgrow spaces, I return to spend quiet, leisurely time to again bloom and go dormant, become more beautiful.