The Profound Struggle Between Yehudah and Yosef the Judaism Site

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Players: Torah - God Midrash Bereshit Rabbah Midrash Devarim Rabbah Rashi - R

Players: Torah - God Midrash Bereshit Rabbah Midrash Devarim Rabbah Rashi - R. Shlomo Yitzhaki (1040-1105) Ibn Ezra - R. Avraham ibn Ezra (1092-1167) Ramban - R. Moshe ben Nahman Gerondi (1194-1270) Zohar - R. Moshe de Leon (1250-1305) Seforno - R. Ovadiah ben Yaakov Seforno (1475-1550) Sefat Emet – R. Yehudah Aryeh Leib Alter (1847-1905) Martin Buber (1878-1965) Rabbi Bradley Shavit Artson - Dean, Ziegler School of Rabbinic Studies Rabbi Cheryl Peretz - Associate Dean, Ziegler School of Rabbinic Studies Dr. Richard Elliot Friedman - Ann and Jay Davis Professor of Jewish Studies, University of Georgia. Obi-Wan Kenobi – Really Powerful Jedi Master Narrator: Rabbi Aaron Alexander – Assistant Dean, Ziegler School of Rabbinic Studies Genesis 6:9: “These are the records of Noah. He was a virtuous man. He was unblemished in his age...” Narrator: Hey! Why do we have these additional words "in his age"? Couldn’t the Torah have just said that Noah was virtuous and righteous? Rashi: Well, the Midrash claims that this seemingly superfluous phrase can be read in two different ways. 1) It is to Noah's praise. If he had lived in a time where being righteous was common, he would have been seen as extremely righteous. 2) On the other hand, “in his age” could also be read to his discredit. He was only righteous in the age that he lived. If, however, he had lived in Abraham’s generation, he would have been your average Joe! Ramban: Rashi, seriously; the correct read is that Noah alone was the righteous man in his age, worthy of being saved from the flood. -

Heavy Heart the Judaism Site

Torah.org Heavy Heart The Judaism Site https://torah.org/torah-portion/dvartorah-5760-bo/ HEAVY HEART by Rabbi Dovid Green "And G-d said to Moshe 'come to Pharaoh, for I have made his heart heavy...'" This means that G-d Himself gave Pharaoh the strength to stand up against His coercion to free the Children of Israel. G-d made clear to Moshe that He is behind the difficulties which the Children of Israel were experiencing. Had we been in Egypt, we might have just seen a very stubborn Pharaoh and felt the oppression of his domination over us. We may have wondered when and if this all would end. However, the truth of the matter is that G-d Himself was really at the helm, navigating. Rabbi Yehudah Aryeh Leib Alter (19th cent.) writes in "Sfas Emes" that from this parsha one can derive much encouragement in facing the hardships we encounter in trying to do the right thing. G- d, Who has only our good in mind, is the One Who is maintaining the hardships we may find ourselves in. Nevertheless, just as in Egypt, our difficulties are purposeful. One might conclude from the existence of opposition to good that G-d is weak. Rabbi Alter points out that it is really just the opposite. The patience and control that G-d shows by giving mankind strength to go against His will is a more profound manifestation of strength than that of obliterating evil. A great rabbi once sent his son out to collect money for an urgent cause. -

Lelov: Cultural Memory and a Jewish Town in Poland. Investigating the Identity and History of an Ultra - Orthodox Society

Lelov: cultural memory and a Jewish town in Poland. Investigating the identity and history of an ultra - orthodox society. Item Type Thesis Authors Morawska, Lucja Rights <a rel="license" href="http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc-nd/3.0/"><img alt="Creative Commons License" style="border-width:0" src="http://i.creativecommons.org/l/by- nc-nd/3.0/88x31.png" /></a><br />The University of Bradford theses are licenced under a <a rel="license" href="http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/">Creative Commons Licence</a>. Download date 03/10/2021 19:09:39 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10454/7827 University of Bradford eThesis This thesis is hosted in Bradford Scholars – The University of Bradford Open Access repository. Visit the repository for full metadata or to contact the repository team © University of Bradford. This work is licenced for reuse under a Creative Commons Licence. Lelov: cultural memory and a Jewish town in Poland. Investigating the identity and history of an ultra - orthodox society. Lucja MORAWSKA Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Social and International Studies University of Bradford 2012 i Lucja Morawska Lelov: cultural memory and a Jewish town in Poland. Investigating the identity and history of an ultra - orthodox society. Key words: Chasidism, Jewish History in Eastern Europe, Biederman family, Chasidic pilgrimage, Poland, Lelov Abstract. Lelov, an otherwise quiet village about fifty miles south of Cracow (Poland), is where Rebbe Dovid (David) Biederman founder of the Lelov ultra-orthodox (Chasidic) Jewish group, - is buried. -

Sefat Emet, Bereshit/Hanukkah (5661/1901)

Sefat Emet, Bereshit/Hanukkah (5661/1901) ספר שפת אמת - בראשית - לחנוכה - שנת ]תרס"א[ איתא ברוקח, כי הל"ו נרות דחנוכה מול הל"ו שעות שהאיר אור הגנוז בששת ימי בראשית ע"ש ]בר"ר י"א ב'[. א"כ )אם כן( נראה שנר חנוכה הוא מאור הגנוז, והוא מאיר בתוך החושך הגדול. זהו שרמזו שמאיר מסוף העולם ועד סופו , שאין העלם וסתר עומד נגד זה האור . We find in the book HaRoke’ach [R. Eliezer of Worms, 1176-1238] that the 36 candles of Hanukkah [without the 8 extra of the shammash] are parallel to the thirty-six hours that the original light of Creation shined in the world before being hidden away [see Genesis Rabbah 11:2]. If this is so, then the light of Hanukkah is itself of that hidden light, which [now] shines in the great darkness [of exile]. The Sages taught that this light shined from one end of the world to the other [Genesis Rabbah 11:2], so no hiding or concealment can stand before this light. כי העולם נק' הטבע, שהוא מעלים ומסתיר האור. אבל אור הראשון הי' מאיר בכל אלה ההסתרות וגנזו לצדיקים. וע"ז )ועל זה( כתיב "זרח בחושך אור לישרים". וכ' )וכתיב( "העם ההולכים בחושך ראו אור גדול" . and conceals this (מעלים ;is also called “nature”, as it hides (ma’alim (העולם ;The world (ha’olam light. Still, that original light shined in all those concealed places, where it was hidden away for the righteous. It is in this sense that we read “A light shines in the darkness for the upright” (Ps. -

Chassidus on the Chassidus on the Parsha +

LIGHTS OF OUR RIGHTEOUS TZADDIKIM בעזרת ה ' יתבר A Tzaddik, or righteous person , makes everyone else appear righteous before Hashem by advocating for them and finding their merits. Kedushas Levi, Parshas Noach (Bereishis 7:1) SH EVI’I SHEL PESACH _ CHASSIDUS ON THE PARSHA + Dvar Torah Shevi’i Shel Pesach – Kerias Yam Suf Walking on Dry Land Even in the Sea “And Bnei Yisrael walked on dry land in the sea” (Shemos 14:29) How can you walk on dry land in the sea? The Noam Elimelech , in Likkutei Shoshana , explains this contradictory-sounding pasuk as follows: When Bnei Yisrael experienced the Exodus and the splitting of the sea, they witnessed tremendous miracles and unbelievable wonders. There are Tzaddikim among us whose h earts are always attuned to Hashem ’s wonders and miracles even on a daily basis; they see not common, ordinary occurrences – they see miracles and wonders. As opposed to Bnei Yisrael, who witnessed the miraculous only when they walked on dry land in the sp lit sea, these Tzaddikim see a miracle as great as the “splitting of the sea” even when walking on so -called ordinary, everyday dry land! Everything they experience and witness in the world is a miracle to them. This is the meaning of our pasuk : there are some among Bnei Yisrael who, even while walking on dry land, experience Hashem ’s greatness and awesome miracles just like in the sea! This is what we mean when we say that Hashem transformed the sea into dry land. Hashem causes the Tzaddik to witness and e xperience miracles as wondrous as the splitting of the sea, even on dry land, because the Tzaddik constantly walks attuned to Hashem ’s greatness and exaltedness. -

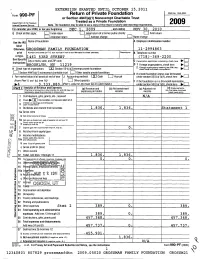

Form 990-PF Return of Private Foundation

EXTENSION GRANTED UNTIL OCTOBER 15,2011 Return of Private Foundation OMB No 1545-0052 Form 990-PF a or Section 4947(a)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust Treated as a Private Foundation Department of the Treasury 2009 Internal Revenue Service Note. The foundation may be able to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirements. For calendar year 2009, or tax year beginning DEC 1, 200 9 , and ending NOV 30, 2010 G Check all that apply: Initial return 0 Initial return of a former public charity LJ Final return n Amended return n Address chance n Name chance of foundation A Employer identification number Use the IRS Name label Otherwise , ROSSMAN FAMILY FOUNDATION 11-2994863 print Number and street (or P O box number if mad is not delivered to street address) Room/suite B Telephone number ortype. 1461 53RD STREET ( 718 ) -369-2200 See Specific City or town, state, and ZIP code C If exem p tion app lication is p endin g , check here 10-E] Instructions 0 1 BROOKLYN , NY 11219 Foreign organizations, check here ► 2. Foreign aanizations meeting % test, H Check type of organization. ®Section 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation chec here nd att ch comp t atiooe5 Section 4947(a )( nonexem pt charitable trust 0 Other taxable private foundation 1 ) E If p rivate foundation status was terminated I Fair market value of all assets at end of year J Accounting method: ® Cash 0 Accrual under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here (from Part Il, co! (c), line 16) 0 Other (specify) F If the foundation is in a 60-month terminatio n $ 3 , 333 , 88 0 . -

Hasidic Judaism - Wikipedia, the Freevisited Encyclopedi Ona 1/6/2015 Page 1 of 19

Hasidic Judaism - Wikipedia, the freevisited encyclopedi ona 1/6/2015 Page 1 of 19 Hasidic Judaism From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Sephardic pronunciation: [ħasiˈdut]; Ashkenazic , תודיסח :Hasidic Judaism (from the Hebrew pronunciation: [χaˈsidus]), meaning "piety" (or "loving-kindness"), is a branch of Orthodox Judaism that promotes spirituality through the popularization and internalization of Jewish mysticism as the fundamental aspect of the faith. It was founded in 18th-century Eastern Europe by Rabbi Israel Baal Shem Tov as a reaction against overly legalistic Judaism. His example began the characteristic veneration of leadership in Hasidism as embodiments and intercessors of Divinity for the followers. [1] Contrary to this, Hasidic teachings cherished the sincerity and concealed holiness of the unlettered common folk, and their equality with the scholarly elite. The emphasis on the Immanent Divine presence in everything gave new value to prayer and deeds of kindness, alongside rabbinical supremacy of study, and replaced historical mystical (kabbalistic) and ethical (musar) asceticism and admonishment with Simcha, encouragement, and daily fervor.[2] Hasidism comprises part of contemporary Haredi Judaism, alongside the previous Talmudic Lithuanian-Yeshiva approach and the Sephardi and Mizrahi traditions. Its charismatic mysticism has inspired non-Orthodox Neo-Hasidic thinkers and influenced wider modern Jewish denominations, while its scholarly thought has interested contemporary academic study. Each Hasidic Jews praying in the Hasidic dynasty follows its own principles; thus, Hasidic Judaism is not one movement but a synagogue on Yom Kippur, by collection of separate groups with some commonality. There are approximately 30 larger Hasidic Maurycy Gottlieb groups, and several hundred smaller groups. Though there is no one version of Hasidism, individual Hasidic groups often share with each other underlying philosophy, worship practices, dress (borrowed from local cultures), and songs (borrowed from local cultures). -

Parshat Vayakhel- Pikudei

ב ס ״ ד Torah Wise Of Heart “Let all those Mount Sinai, the only time in all defeat of tragedy: “Wherever it wise of heart come and do”— history when an entire people says ‘and there will be,’ it is a Exodus 35:10. Moses called became the recipients of sign of impending joy.” Weekly revelation. Then came the (Bamidbar Rabbah 13.) At a upon each individual member of the Children of Israel to come disappearance of Moses for his deeper level, though, the opening March 15-21, 2020 forward and use their particular long sojourn at the top of the verse of the sedra alerts us to the 19-25 Adar, 5780 skill (“wisdom”) to build mountain, an absence which led nature of community in Judaism. First Torah: Vayak'hel- to the Israelites’ greatest In classical Hebrew there are Pekudei: Exodus 35:1 - 40:38 the Mishkan—the Second Torah: Parshat desert Tabernacle. collective sin, the making of three different words for Hachodesh: Exodus 12:1-20 The Mishkan was an amazing the golden calf. Moses returned community: edah, tzibbur and ke work of art and engineering, and to the mountain to plead for hillah; and they signify different Haftorah: much wisdom and skill were forgiveness, which was granted. kinds of association. Edah comes Ezekiel 45:18 - 46:15 required to build it. But why does Its symbol was the second set of from the word ed, meaning PARSHAT VAYAK’HEL- he issue a call for the “wise tablets. Now life must begin “witness.” The PEKUDEI of heart”? Is this not a again. -

Women and Hasidism: a “Non-Sectarian” Perspective

Jewish History (2013) 27: 399–434 © The Author(s) 2013. This article is published DOI: 10.1007/s10835-013-9190-x with open access at Springerlink.com Women and Hasidism: A “Non-Sectarian” Perspective MARCIN WODZINSKI´ University of Wrocław, Wrocław, Poland E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Hasidism has often been defined and viewed as a sect. By implication, if Hasidism was indeed a sect, then membership would have encompassed all the social ties of the “sectari- ans,” including their family ties, thus forcing us to consider their mothers, wives, and daughters as full-fledged female hasidim. In reality, however, women did not become hasidim in their own right, at least not in terms of the categories implied by the definition of Hasidism as a sect. Reconsideration of the logical implications of the identification of Hasidism as a sect leads to a radical re-evaluation of the relationship between the hasidic movement and its female con- stituency, and, by extension, of larger issues concerning the boundaries of Hasidism. Keywords Hasidism · Eastern Europe · Gender · Women · Sectarianism · Family Introduction Beginning with Jewish historiography during the Haskalah period, through Wissenschaft des Judentums, to Dubnow and the national school, scholars have traditionally regarded Hasidism as a sect. This view had its roots in the earliest critiques of Hasidism, first by the mitnagedim and subsequently by the maskilim.1 It attributed to Hasidism the characteristic features of a sect, 1The term kat hahasidim (the sect of hasidim)orkat hamithasedim (the sect of false hasidim or sanctimonious hypocrites) appears often in the anti-hasidic polemics of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. -

Visions of Legal Diversity in Hasidic Literature

The Ever-Changing Path: Visions of Legal Diversity in Hasidic Literature Byline: Ariel Evan Mayse The Ever-Changing Path: Visions of Legal Diversity in Hasidic Literature* Ariel Evan Mayse Judaism is a religion of law. More precisely, it is a way of life consisting of embodied practices and rituals in which we are called upon to express—and cultivate—our private inner worlds. Judaism thus binds theology and praxis, intertwining the spiritual life and physical actions by demanding that God be served neither with pure contemplation nor empty deeds performed by rote. These practices unite the members of the community by imparting a shared structure and behavioral norms, but they are also deeply personal ways of communicating the hidden realms of the spirit. The commandments are sacred vessels that evidence our relationship with God; each one bears witness to our devotion and reveals our theological convictions. But law and spirituality are often framed as opposing forces in the religious life of devoted [1] mystical seekers. In this common understanding, the pneuma (spirit) inspires the mystic to new levels of intimacy with God, while the nomos (law) restrains and binds him to the norms of his community. The strain between these two poles could be deemed fraught or fruitful, but it remains a tension nonetheless. In the context of Judaism this model has been frequently applied to Hasidism, with the assumption that the spiritual quest and the obligatory practices demanded by halakha pull the seeker in opposing trajectories. Recent evaluations of Hasidic literature, however, have reminded us that the early Hasidic masters were deeply immersed in the world of Jewish law. -

צב | עב January Tevet | Sh’Vat Capricorn Saturn | Aquarius Saturn

צב | עב January Tevet | Sh’vat Capricorn Saturn | Aquarius Saturn Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday 1 | 17th of Tevet* 2 | 18th of Tevet* New Year’s Day Parashat Vayechi Abraham Moshe Hillel Rabbi Tzvi Elimelech of Dinov Rabbi Salman Mutzfi Rabbi Huna bar Mar Zutra & Rabbi Rabbi Yaakov Krantz Mesharshya bar Pakod Rabbi Moshe Kalfon Ha-Cohen of Jerba 3 | 19th of Tevet * 4* | 20th of Tevet 5 | 21st of Tevet * 6 | 22nd of Tevet* 7 | 23rd of Tevet* 8 | 24th of Tevet* 9 | 25th of Tevet* Parashat Shemot Rabbi Menchachem Mendel Yosef Rabbi Moshe ben Maimon Rabbi Leib Mochiach of Polnoi Rabbi Hillel ben Naphtali Zevi Rabbi Shneur Zalman of Liadi Rabbi Yaakov Abuchatzeira Rabbi Yisrael Dov of Vilednik Rabbi Schulem Moshkovitz Rabbi Naphtali Cohen Miriam Mizrachi Rabbi Shmuel Bornsztain Rabbi Eliyahu Eliezer Dessler 10 | 26th of Tevet* 11 | 27th of Tevet* 12 | 28th of Tevet* 13* | 29th of Tevet 14* | 1st of Sh’vat 15* | 2nd of Sh’vat 16 | 3rd of Sh’vat* Rosh Chodesh Sh’vat Parashat Vaera Rabbeinu Avraham bar Dovid mi Rabbi Shimshon Raphael Hirsch HaRav Yitzhak Kaduri Rabbi Meshulam Zusha of Anipoli Posquires Rabbi Yehoshua Yehuda Leib Diskin Rabbi Menahem Mendel ben Rabbi Shlomo Leib Brevda Rabbi Eliyahu Moshe Panigel Abraham Krochmal Rabbi Aryeh Leib Malin 17* | 4th of Sh’vat 18 | 5th of Sh’vat* 19 | 6th of Sh’vat* 20 | 7th of Sh’vat* 21 | 8th of Sh’vat* 22 | 9th of Sh’vat* 23* | 10th of Sh’vat* Parashat Bo Rabbi Yisrael Abuchatzeirah Rabbi Yehudah Aryeh Leib Alter Rabbi Chaim Tzvi Teitelbaum Rabbi Nathan David Rabinowitz -

Bal Tashchit : the Jewish Prohibition Against Needless Destruction Wolff, K.A

Bal Tashchit : the Jewish prohibition against needless destruction Wolff, K.A. Citation Wolff, K. A. (2009, December 1). Bal Tashchit : the Jewish prohibition against needless destruction. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/14448 Version: Corrected Publisher’s Version Licence agreement concerning inclusion of doctoral thesis in the License: Institutional Repository of the University of Leiden Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/14448 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). BAL TASHCHIT: THE JEWISH PROHIBITION AGAINST NEEDLESS DESTRUCTION Copyright © 2009 by K. A. Wolff All rights reserved Printed in Jerusalem BAL TASHCHIT: THE JEWISH PROHIBITION AGAINST NEEDLESS DESTRUCTION Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van Doctor aan de Universiteit Leiden, op gezag van de Rector Magnificus prof. mr P.F. van der Heijden, volgens besluit van het College voor Promoties te verdedigen op dinsdag 1 december 2009 klokke 15:00 uur door Keith A. Wolff geboren te Fort Lauderdale (Verenigde Staten) in 1957 Promotiecommissie Promotores: Prof. Dr F.A. de Wolff Prof. Dr A. Wijler, Rabbijn, Jerusalem College of Technology Overige leden: Prof. Dr J.J. Boersema, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam Prof. Dr A. Ellian Prof. Dr R.W. Munk, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam Prof. Dr I.E. Zwiep, Universiteit van Amsterdam To my wife, our children, and our parents Preface This is an interdisciplinary thesis. The second and third chapters focus on classic Jewish texts, commentary and legal responsa, including the original Hebrew and Aramaic, along with translations into English. The remainder of the thesis seeks to integrate principles derived from these Jewish sources with contemporary Western thought, particularly on what might be called 'environmental' themes.