Sea Otters and Kelp Forests

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Algae & Marine Plants of Point Reyes

Algae & Marine Plants of Point Reyes Green Algae or Chlorophyta Genus/Species Common Name Acrosiphonia coalita Green rope, Tangled weed Blidingia minima Blidingia minima var. vexata Dwarf sea hair Bryopsis corticulans Cladophora columbiana Green tuft alga Codium fragile subsp. californicum Sea staghorn Codium setchellii Smooth spongy cushion, Green spongy cushion Trentepohlia aurea Ulva californica Ulva fenestrata Sea lettuce Ulva intestinalis Sea hair, Sea lettuce, Gutweed, Grass kelp Ulva linza Ulva taeniata Urospora sp. Brown Algae or Ochrophyta Genus/Species Common Name Alaria marginata Ribbon kelp, Winged kelp Analipus japonicus Fir branch seaweed, Sea fir Coilodesme californica Dactylosiphon bullosus Desmarestia herbacea Desmarestia latifrons Egregia menziesii Feather boa Fucus distichus Bladderwrack, Rockweed Haplogloia andersonii Anderson's gooey brown Laminaria setchellii Southern stiff-stiped kelp Laminaria sinclairii Leathesia marina Sea cauliflower Melanosiphon intestinalis Twisted sea tubes Nereocystis luetkeana Bull kelp, Bullwhip kelp, Bladder wrack, Edible kelp, Ribbon kelp Pelvetiopsis limitata Petalonia fascia False kelp Petrospongium rugosum Phaeostrophion irregulare Sand-scoured false kelp Pterygophora californica Woody-stemmed kelp, Stalked kelp, Walking kelp Ralfsia sp. Silvetia compressa Rockweed Stephanocystis osmundacea Page 1 of 4 Red Algae or Rhodophyta Genus/Species Common Name Ahnfeltia fastigiata Bushy Ahnfelt's seaweed Ahnfeltiopsis linearis Anisocladella pacifica Bangia sp. Bossiella dichotoma Bossiella -

And Red Sea Urchins

NEGATIVELY CORRELATED ABUNDANCE SUGGESTS COMPETITION BETWEEN RED ABALONE (Haliotis rufescens) AND RED SEA URCHINS (Mesocentrotus franciscanus) INSIDE AND OUTSIDE ESTABLISHED MPAs CLOSED TO COMMERCIAL SEA URCHIN HARVEST IN NORTHERN CALIFORNIA By Johnathan Centoni A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of Humboldt State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in Biology Committee Membership Dr. Sean Craig, Committee Chair Dr. Brian Tissot, Committee Member Dr. Paul Bourdeau, Committee Member Dr. Joe Tyburczy, Committee Member Dr. Erik Jules, Program Graduate Coordinator May 2018 ABSTRACT NEGATIVELY CORRELATED ABUNDANCE SUGGESTS COMPETITION BETWEEN RED ABALONE (Haliotis rufescens) AND RED SEA URCHINS (Mesocentrotus franciscanus) INSIDE AND OUTSIDE ESTABLISHED MPAs CLOSED TO COMMERCIAL SEA URCHIN HARVEST IN NORTHERN CALIFORNIA Johnathan Centoni Red abalone and sea urchins are both important herbivores that potentially compete with each other for resources like food and space along the California coast. Red abalone supported a socioeconomically important recreational fishery during this study (which was closed in 2018) and red sea urchins support an important commercial fishery. Both red sea urchins and red abalone feed on the same macroalgae (including Pterygophora californica, Laminaria setchellii, Stephanocystis osmundacea, Costaria costata, Alaria marginata, Nereocystis leutkeana), and a low abundance of this food source during the period of this project may have created a highly competitive environment for urchins and abalone. Evidence that suggests competition between red abalone and red sea urchins can be seen within data collected during the years of this study (2014-2016): a significantly higher red sea urchin density, concomitant with a significantly lower red abalone density, was observed within areas closed to commercial sea urchin harvest (in MPAs) compared to nearby reference areas open to sea urchin harvest. -

Biomechanical Analysis of Wave-Induced Mortality in the Marine Alga Pterygophora Californica

MARINE ECOLOGY - PROGRESS SERIES Vol. 36: 163-170, 1987 Published March 2 Mar. Ecol. hog. Ser. Biomechanical analysis of wave-induced mortality in the marine alga Pterygophora californica Richard F. Biedka, John M. Gosline & Robert E. De Wreede Departments of Zoology and Botany, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia V6T 2B1, Canada ABSTRACT: A biomechanical analysis was carried out on the stipe of the marine brown alga Pterygophora cahfornica (Ruprecht). Tensile and compressive mechanical tests on the cortical material revealed that the plant is constructed from a reasonably stiff (tensile modulus of elasticity = 60 MN m-2), strong (tensile strength = 9 MN m-2) and extensible (fdure strain = 0.49) material. Consequently, the stipe is a very robust structure that is extremely difficult to break. However, the work of fracture of the cortical material is only about 400 J m-', making it a relatively brittle material. Thus, it is expected that small notches or flaws at the stipe surface will dramatically reduce the ability of the stipe to resist bending forces caused by waves. Fracture mechanics analysis suggests a critical flaw size for the cortical material of about 0.2 mm, and any surface defect larger than this size will degrade the mechanical strength of the plant. The red urchin Strongylocentrotus franciscanus is known to graze on the stipe of P. californica. This grazing is known to mtroduce surface flaws an order of magnitude or more larger than the critical flaw size, and therefore it IS very likely that such grazlng will make a substantial contribution to wave-induced mortahty of these plants. -

The Classification of Lower Organisms

The Classification of Lower Organisms Ernst Hkinrich Haickei, in 1874 From Rolschc (1906). By permission of Macrae Smith Company. C f3 The Classification of LOWER ORGANISMS By HERBERT FAULKNER COPELAND \ PACIFIC ^.,^,kfi^..^ BOOKS PALO ALTO, CALIFORNIA Copyright 1956 by Herbert F. Copeland Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 56-7944 Published by PACIFIC BOOKS Palo Alto, California Printed and bound in the United States of America CONTENTS Chapter Page I. Introduction 1 II. An Essay on Nomenclature 6 III. Kingdom Mychota 12 Phylum Archezoa 17 Class 1. Schizophyta 18 Order 1. Schizosporea 18 Order 2. Actinomycetalea 24 Order 3. Caulobacterialea 25 Class 2. Myxoschizomycetes 27 Order 1. Myxobactralea 27 Order 2. Spirochaetalea 28 Class 3. Archiplastidea 29 Order 1. Rhodobacteria 31 Order 2. Sphaerotilalea 33 Order 3. Coccogonea 33 Order 4. Gloiophycea 33 IV. Kingdom Protoctista 37 V. Phylum Rhodophyta 40 Class 1. Bangialea 41 Order Bangiacea 41 Class 2. Heterocarpea 44 Order 1. Cryptospermea 47 Order 2. Sphaerococcoidea 47 Order 3. Gelidialea 49 Order 4. Furccllariea 50 Order 5. Coeloblastea 51 Order 6. Floridea 51 VI. Phylum Phaeophyta 53 Class 1. Heterokonta 55 Order 1. Ochromonadalea 57 Order 2. Silicoflagellata 61 Order 3. Vaucheriacea 63 Order 4. Choanoflagellata 67 Order 5. Hyphochytrialea 69 Class 2. Bacillariacea 69 Order 1. Disciformia 73 Order 2. Diatomea 74 Class 3. Oomycetes 76 Order 1. Saprolegnina 77 Order 2. Peronosporina 80 Order 3. Lagenidialea 81 Class 4. Melanophycea 82 Order 1 . Phaeozoosporea 86 Order 2. Sphacelarialea 86 Order 3. Dictyotea 86 Order 4. Sporochnoidea 87 V ly Chapter Page Orders. Cutlerialea 88 Order 6. -

Ochrophyta Part II Notebook Requirements (14 Drawings) 1

Ochrophyta Part II Notebook Requirements (14 drawings) 1. Desmarestia sp.- 2 drawings (thallus from press and trichothallic growth) 2. Laminaria setchelli- 3 drawings (thallus and sorus cross section) 3. Macrocystis pyrifera – 4drawings (entire thallus, apical end, transverse cross section, longitudinal section) 4. Nereocystis leutkeana – 1 drawings (entire thallus) 5. Pterygophora californica – 1 drawing (entire thallus) 6. Alaria marginata – 1 drawing (entire thallus from press) 7. Egregia menziesii – 2 drawing (entire thallus of adult plant, one brach of a young plant) 8. Unknown(s) - steps to key D. Order Desmarestiales Species: Desmarestia spp. • Draw the entire thallus of Desmarestia. (Use the herbarium pressing) • Look at a prepared slide and draw what you see. Q: What kind of growth does Desmarestia exhibit? E. Order Laminariales Family Laminariaceae Species: Laminaria setchellii The holdfast of this species is composed of stiff, branched haptera. Each holdfast produces a single, long stipe. Sori appear as irregular darkened patches on the blades, but not all blades have sori. 1. Prepare and draw a cross section of the sorus. Look for and label sporangia, cortex and medulla. 2. Examine and draw the overall thallus. Label holdfast, stipe, blade, sori and the location of the meristem. 3. Look at the prepared slide, draw and label what you see. Species: Macrocystis pyrifera To transport sugars throughout the plant body of this large kelp, M. pyrifera has sieve elements in the medulla. • Examine and sketch the thallus of M. pyrifera. Label stipe, blades, sporophylls, holdfast, pneumatocysts and location of intercalary meristem. • Examine and sketch the apical end of M. pyrifera noting the scimitar blade. -

Californica (Phaeophyta)

Vol. 19: 93-100, 1984 MARINE ECOLOGY - PROGRESS SERIES Published August 30 Mar. Ecol. hog. Ser. Growth and age class distribution of Pterygophora californica (Phaeophyta) R. E. De Wreede Department of Botany. The University of Brltlsh Columbia, Vancouver. B.C. V61 2B1, Canada ABSTRACT: Pterygophora califomica Ruprecht (Laminariales, Phaeophyta) is a perennial brown alga often found in the upper subtidal zone of oceanic coastal sites of British Columbia, Canada. The phenology and age class distribution of P. californica was studied for over 2 yr at 3 study sites in Barkley Sound, British Columbia. Maximum elongation of stipes, apical blades, and sporophylls generally occurred from (Feb) Mar to Jun, and the minimum from Oct to Dec (Jan). Stipe elongation varies within and among sites (5.4 to 18.2 cm yr-l). Sporophylls made up 50 % of the total dry weight (minus holdfast) but the apical blade never exceeded 7 %. Stipe rings formed once a year, and this information was used to estimate age class distributions. At each study site there were very few young (< 2 yr) and old (> 9 yr) individuals. Based on age class distribution and other observations, the pattern of settlement and survival appears to be similar at the 3 sites. An existing population is decimated (probably by a combination of sea urchins and storms), followed by relatively high annual recruitment and survival rates for 3 to 4 yr. Subsequently there is little new recruitment until the adult plants once more disappear. known, a tool is available for studying both the age structure of a population and age associated Pterygophora californica Ruprecht is a perennial phenomena. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Planktonic Patterns And

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Planktonic Patterns and Processes in the Giant Kelp Macrocystis pyrifera A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Oceanography by Michael Hall Graham Committee in charge: Paul K. Dayton, Chair Nicholas D. Holland Lisa A. Levin B. Greg Mitchell Brad Werner Chris Wills Richard K. Zimmer 2000 Copyright Michael Hall Graham, 2000 All rights reserved The dissertation of Michael Hall Graham is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm: Chair University of California, San Diego 2000 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page ……………………………………………………………………. iii Table of Contents …………………………………………………………………. iv List of Figures ……………………………………………………………………. vi List of tables ……………………………………………………………………… viii Dedication ………………………………………………………………………... ix Epigraph ………………………………………………………………………….. x Acknowledgments ………………………………………………………………… xi Vita and Publications ……………………………………………………..………. xv Abstract …………………………………………………………………………… xvi I. Introduction ………………………………………………………………….…. 1 Figures …………………………………………………………………….….. 6 Literature Cited …………………………………………………………….….. 7 II. Obtaining absorption spectra from individual macroalgal spores using microphotometry …………………………………………………………. 9 Abstract …………………………………………………………..…...………. 9 Introduction ……………………………………………….…………….……. 10 Methods ………………………………………………………………...……. 11 Sample preparation …………………………………………….…………. 11 Kelp zoospores …………………………………………………….…. 11 Red algal tetraspores ……………………………………….…………. 12 Microphotometry -

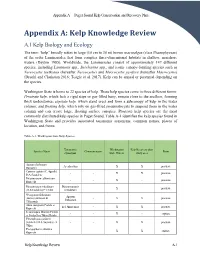

Appendix A: Kelp Knowledge Review

Appendix A — Puget Sound Kelp Conservation and Recovery Plan Appendix A: Kelp Knowledge Review A.1 Kelp Biology and Ecology The term “kelp” broadly refers to large (10 cm to 30 m) brown macroalgae (class Phaeophyceae) of the order Laminariales that form complex three-dimensional habitats in shallow, nearshore waters (Dayton 1985). Worldwide, the Laminariales consist of approximately 147 different species, including Laminaria spp., Saccharina spp., and iconic canopy-forming species such as Nereocystis luetkeana (hereafter Nereocystis) and Macrocystis pyrifera (hereafter Macrocystis) (Druehl and Clarkston 2016; Teagle et al. 2017). Kelp can be annual or perennial depending on the species. Washington State is home to 22 species of kelp. These kelp species come in three different forms: Prostrate kelp, which lack a rigid stipe or gas-filled buoy, remain close to the seafloor, forming thick understories; stipitate kelp, which stand erect and form a subcanopy of kelp in the water column; and floating kelp, which rely on gas-filled pneumatocysts to suspend them in the water column and can create large, floating surface canopies. Prostrate kelp species are the most commonly distributed kelp species in Puget Sound. Table A-1 identifies the kelp species found in Washington State and provides associated taxonomic synonyms, common names, places of location, and forms. Table A-1. Washington State Kelp Species. Taxonomic Washington Kelp Recovery plan Species Name Common name Form synonyms State Waters study area Agarum clathratum A. cribrosum - X X prostrate Dumortier Costaria costata (C. Agardh) - - X X prostrate D.A. Saunders Dictyoneurum californicum - - X - prostrate Ruprecht Dictyoneurum reticulatum Dictyoneuropsis - X - prostrate (D.A.Saunders) P.C.Silva reticulatum Neoagarum fimbriatum Agarum (Harvey) H.Kawai & - X X prostrate fimbriatum T.Hanyuda Alaria marginata Postels et incl. -

Laminariales, Phaeophyceae) Supports Substantial Taxonomic Re-Organization1

J. Phycol. 42, 493–512 (2006) r 2006 Phycological Society of America DOI: 10.1111/j.1529-8817.2006.00204.x A MULTI-GENE MOLECULAR INVESTIGATION OF THE KELP (LAMINARIALES, PHAEOPHYCEAE) SUPPORTS SUBSTANTIAL TAXONOMIC RE-ORGANIZATION1 Christopher E. Lane,2 Charlene Mayes Centre for Environmental and Molecular Algal Research, University of New Brunswick, Fredericton, NB, Canada E3B 6E1 Louis D. Druehl Bamfield Marine Sciences Centre, Bamfield, BC, Canada V0R 1B0 and Gary W. Saunders Centre for Environmental and Molecular Algal Research, University of New Brunswick, Fredericton, NB, Canada E3B 6E1 Every year numerous ecological, biochemical, Key index words: Costariaceae; Laminariales; long and physiological studies are performed using branch attraction; nested analyses; phylogenetics; members of the order Laminariales. Despite the Saccharina fact that kelp are some of the most intensely stud- ied macroalgae in the world, there is significant de- bate over the classification within and among the The order Laminariales Migula, commonly called three ‘‘derived’’ families, the Alariaceae, Lamina- kelp, includes the largest algae in the world, reaching riaceae, and Lessoniaceae (ALL). Molecular phylo- up to 50 m in length (Van den Hoek et al. 1995). Kelp genies published for the ALL families have are ubiquitous in coastal waters of cold-temperate re- generated hypotheses strongly at odds with the cur- gions from the Arctic to the Antarctic, and their size rent morphological taxonomy; however, conflicting and biomass establishes a unique and essential habitat phylogenetic hypotheses and consistently low levels for hundreds of species (Steneck et al. 2002). They are of support realized in all of these studies have re- used as a food source in Asia and Europe, and are also sulted in conservative approaches to taxonomic re- economically important for their extracts (Chapman visions. -

Nested PCR Detection of Microscopic Life-Stages of Laminarian Macroalgae and Comparison with Adult Forms Along Intertidal Height Gradients

MARINE ECOLOGY PROGRESS SERIES Vol. 332: 1–10, 2007 Published March 5 Mar Ecol Prog Ser OPENPEN ACCESSCCESS FEATURE ARTICLE Nested PCR detection of microscopic life-stages of laminarian macroalgae and comparison with adult forms along intertidal height gradients Caroline H. Fox, Andrew K. Swanson* Department of Biology, Millis Hall, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio 44106, USA ABSTRACT: Recruitment of kelp species (Laminari- ales) to rocky marine habitats relies on the prior establishment of microscopic life-stages (zoospores, gametophytes, gametes and microscopic sporo- phytes). Unlike macroscopic sporophyte stages of kelp, microscopic life-stages have proved difficult to detect and identify in their natural habitat. Using a species-specific PCR-based assay, we developed a method to detect putative microscopic life-stages of 2 northeast Pacific kelp species, Nereocystis luetkeana (Mertens) Postels et Ruprecht and Hedophyllum ses- sile (C. Agardh) Setchell, from rocky intertidal sub- strate samples. Species-specific primers were evalu- ated for specificity and sensitivity. Comparisons of nested and unnested PCR were performed for both species. Nested PCR was used to screen for target species present on rocks obtained along an intertidal height gradient (0.0 to 3.5 m Lowest Low Water Microscopic life-stages of kelp are difficult to identify in [LLW]) from 2 sites at monthly intervals in summer nature. A nested PCR assay was used to detect and monitor 2005. Vertical distribution patterns of the putative the distribution of microscopic life-stages of 2 intertidal microscopic life-stages and the macroscopic sporo- Pacific kelp species, Nereocystis luetkeana and Hedophyllum phyte form were compared at both sites. -

The Validity of Using Morphological Characteristics As Predictors of Age in the Kelp Pterygophora Californica (Laminariales

Vol. 59: 295304, 1990 MARINE ECOLOGY PROGRESS SERIES Published January 25 Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. The validity of using morphological characteristics as predictors of age in the kelp Pterygophora californica (Laminariales,Phaeophyta) Zachary P. Hymanson*,Daniel C. Reed", Michael S. Foster, John W. Carter8** Moss Landing Marine Laboratories. PO Box 450. Moss Landing, California 95039. USA ABSTRACT: Previous studies have used stipe ring counts to estimate the age of several species in the Laminariales. Although this method is widely accepted, it has rarely been validated. To test the validity of aging Pterygophora californica by counting rings formed in the stipe, we sampled plants of known age between 1.0 and 4.4 yr old and plants with a calculated age of 12 yr. For a given cohort, the number of complete rings closely approximated the known age in years, indicating ring counts are a reliable method for estimating the age structure of P. californica populations. However, ring counts from individual plants of known age can vary by f 2 yr (95 % CI), and among readers counting the same plants by k 1 yr (95 % CI). Single plants, therefore, could not be reliably aged by ring counts. Linear relationships between 2 morphometric measures (stipe length and stipe diameter) and number of rings varied both within and between stands and sites, suggesting these measures are not reliable for estimating the age of th~salga in the areas sampled Stand d.ensity may be an important factor contributing to the variation in these morphometric measures. Short-term (22 wk) field manipulations of stand density showed that plants at high density (30 plants m-') grew faster in stipe length and slower in stipe diameter than those at medum (6 plants m-2) and low (2 plants m-') densities. -

Factors Influencing Recruitment and Appearance of Bull Kelp, Nereocystis Luetkeana (Phylum Ochrophyta) Katie Dobkowski Bates College, [email protected]

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Bates College: SCARAB (Scholarly Communication and Research at Bates) Bates College SCARAB All Faculty Scholarship Departments and Programs 11-22-2018 Factors influencing recruitment and appearance of bull kelp, Nereocystis luetkeana (phylum Ochrophyta) Katie Dobkowski Bates College, [email protected] K. Darby Flanagan Jessica R. Nordstrom Follow this and additional works at: https://scarab.bates.edu/faculty_publications Recommended Citation Dobkowski, K. A., Flanagan, K. D. and Nordstrom, J. R. (2018), Factors influencing recruitment and appearance of bull kelp, Nereocystis luetkeana (phylum Ochrophyta). J. Phycol.. Accepted Author Manuscript. doi:10.1111/jpy.12814 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Departments and Programs at SCARAB. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of SCARAB. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 FACTORS INFLUENCING RECRUITMENT AND APPEARANCE OF BULL KELP, NEREOCYSTIS 2 LUETKEANA (PHYLUM OCHROPHYTA)1 3 4 Running Title: Influences on N. luetkeana recruitment 5 6 Katie A. Dobkowski2, University of Washington and Friday Harbor Laboratories 7 8 K. Darby Flanagan, University of Washington and Friday Harbor Laboratories 9 10 Jessica R. Nordstrom, Friday Harbor Labs and Point Defiance Zoo and Aquarium 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 1 – Submitted 11/12/2018 44 2 – Current Contact Information: [email protected], Bates College, 44 Campus Ave, 45 Department of Biology, Lewiston, ME 04240, USA 46 47 Abstract 48 The dynamics of annual species are strongly tied to their capacity for recruitment 49 each year.