Agarsure Village Survey Monograph, Part VI

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Proposal to Connect Mumbai and Alibaug by an Immersed Tunnel –The Analytical Study

ISSN: 2348 9510 International Journal Of Core Engineering & Management (IJCEM) Volume 2, Issue 3, June 2015 A proposal to connect Mumbai and Alibaug by an Immersed Tunnel –The Analytical Study Nitin N. Palande Vidya Pratishtan Collage of Engineering, Civil Dept. Baramati, Pune, India [email protected] Ashlesha V. Dubey Vidya Pratishtan Collage of Engineering, Civil Dept. Baramati, Pune, India [email protected] Abstract The main aim of the project is to connect the two coats of the Dharamtar creek i.e. Rewas in Alibaug and Karanja in Uran by an immersed tunnel. The construction of proposed immersed tunnel will reduce the travel time from Mumbai to Alibaug from 3 hours to 1 hour. But this reduction in time includes the consideration of the sea-link from Sewri to Nhava Seva (Uran).Which was proposed by government and is already under construction. Thus construction of this immersed tunnel will ease the transportation of the city. In this study, a preliminary analysis of immersed tube is carried out. The static and dynamic analysis of the tunnel was made in finite element program. The vertical displacement of the tube unit under static loads was calculated. Afterwards, the seismic analysis was made to investigate stresses developed due to both racking and axial deformation of the tunnel during an earthquake. It was found that, maximum stress due to axial deformation is longer than compressive strength of the concrete. The high stresses in the tube occur, because of the tube stiffness. I. Introduction With the recent rapid development of global economy and engineering technology, tunnel construction has become increasingly important in regional economic and social development. -

Sources of Maratha History: Indian Sources

1 SOURCES OF MARATHA HISTORY: INDIAN SOURCES Unit Structure : 1.0 Objectives 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Maratha Sources 1.3 Sanskrit Sources 1.4 Hindi Sources 1.5 Persian Sources 1.6 Summary 1.7 Additional Readings 1.8 Questions 1.0 OBJECTIVES After the completion of study of this unit the student will be able to:- 1. Understand the Marathi sources of the history of Marathas. 2. Explain the matter written in all Bakhars ranging from Sabhasad Bakhar to Tanjore Bakhar. 3. Know Shakavalies as a source of Maratha history. 4. Comprehend official files and diaries as source of Maratha history. 5. Understand the Sanskrit sources of the Maratha history. 6. Explain the Hindi sources of Maratha history. 7. Know the Persian sources of Maratha history. 1.1 INTRODUCTION The history of Marathas can be best studied with the help of first hand source material like Bakhars, State papers, court Histories, Chronicles and accounts of contemporary travelers, who came to India and made observations of Maharashtra during the period of Marathas. The Maratha scholars and historians had worked hard to construct the history of the land and people of Maharashtra. Among such scholars people like Kashinath Sane, Rajwade, Khare and Parasnis were well known luminaries in this field of history writing of Maratha. Kashinath Sane published a mass of original material like Bakhars, Sanads, letters and other state papers in his journal Kavyetihas Samgraha for more eleven years during the nineteenth century. There is much more them contribution of the Bharat Itihas Sanshodhan Mandal, Pune to this regard. -

MUMBAI an EMERGING HUB for NEW BUSINESSES & SUPERIOR LIVING 2 Raigad: Mumbai - 3.0

MUMBAI AN EMERGING HUB FOR NEW BUSINESSES & SUPERIOR LIVING 2 Raigad: Mumbai - 3.0 FOREWORD Anuj Puri ANAROCK Group Group Chairman With the island city of Mumbai, Navi Mumbai contribution of the district to Maharashtra. Raigad and Thane reaching saturation due to scarcity of is preparing itself to contribute significantly land parcels for future development, Raigad is towards Maharashtra’s aim of contributing US$ expected to emerge as a new destination offering 1 trillion to overall Indian economy by 2025. The a fine balance between work and pleasure. district which is currently dominated by blue- Formerly known as Kolaba, Raigad is today one collared employees is expected to see a reverse of the most prominent economic districts of the in trend with rising dominance of white-collared state of Maharashtra. The district spans across jobs in the mid-term. 7,152 sq. km. area having a total population of 26.4 Lakh, as per Census 2011, and a population Rapid industrialization and urbanization in density of 328 inhabitants/sq. km. The region Raigad are being further augmented by massive has witnessed a sharp decadal growth of 19.4% infrastructure investments from the government. in its overall population between 2001 to 2011. This is also attributing significantly to the overall Today, the district boasts of offering its residents residential and commercial growth in the region, a perfect blend of leisure, business and housing thereby boosting overall real estate growth and facilities. uplifting and improving the quality of living for its residents. Over the past few years, Raigad has become one of the most prominent districts contributing The report titled ‘Raigad: Mumbai 3.0- An significantly to Maharashtra’s GDP. -

5Thmarch 2019

Registration details: Patrons Delegates are requested to send their Hon. Sanjay Datta Patil Registration fees through Demand Draft. The draft President, Janata Shikshan Mandal, Alibag should be drawn in favour of Principal, Adv. Gautam Patil J.S.M.College, Alibag- Raigad, payable at Alibag. Vice-President, Janata Shikshan Mandal, Alibag Participants can also deposit their registration fees Hon. Ajit P. Shah Janata Shikshan Mandal’s online with following account details: Secretary, Janata Shikshan Mandal, Alibag Late. Nanasaheb Kunte Education Complex Account name: Principal, J. S. M. College, Alibag Smt. Indirabai G. Kulkarni Arts College, Account No: 915010024197287 Convener J.B. Sawant Science College and Bank name: Axis Bank; Branch name: Alibag Dr. Anil K. Patil Sau. Janakibai Dhondo Kunte Commerce College. IFSC Code: UTIB0001700 Principal, J. S. M. College, Alibag Alibag, Dist.-Raigad-Maharashtra, India 402201. International Code (Swift Code): AXISINBBA32. Permanently affiliated to University of Mumbai, Registration Fee: Co-Convener Recognised under section 2(f), 12 (B) of the UGC Dr. N. N. Shere Reaccredited with B Grade (3rd Cycle) Category Fees Vice – Principal and Head, Dept. of Marathi e-mail: [email protected] Teachers/Researchers Rs.700/- Registration Website: www.jsmalibag.edu.in/home/Senior Organizing Secretary Dr. Mohsin Khan Prof. M. S. Suryawanshi P.G. / U.G. Students Rs.300/- Registration Head, Dept. of Hindi Head, Dept. of English One Day National Conference Research Scholars on Advisory Committee INDIAN LANGUAGES, LITERATURE AND Conference Registration fees includes access to all Prof. A. M. Oak CULTURE IN THE GLOBAL CONTEXT sessions, Conference kit, Tea, Breakfast, Lunch, and Vice Principal, J.S.M. -

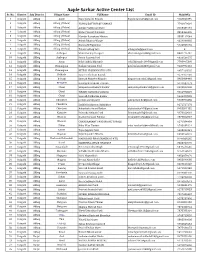

Aaple Sarkar Active Center List Sr

Aaple Sarkar Active Center List Sr. No. District Sub District Village Name VLEName Email ID MobileNo 1 Raigarh Alibag Akshi Sagar Jaywant Kawale [email protected] 9168823459 2 Raigarh Alibag Alibag (Urban) VISHAL DATTATREY GHARAT 7741079016 3 Raigarh Alibag Alibag (Urban) Ashish Prabhakar Mane 8108389191 4 Raigarh Alibag Alibag (Urban) Kishor Vasant Nalavade 8390444409 5 Raigarh Alibag Alibag (Urban) Mandar Ramakant Mhatre 8888117044 6 Raigarh Alibag Alibag (Urban) Ashok Dharma Warge 9226366635 7 Raigarh Alibag Alibag (Urban) Karuna M Nigavekar 9922808182 8 Raigarh Alibag Alibag (Urban) Tahasil Alibag Setu [email protected] 0 9 Raigarh Alibag Ambepur Shama Sanjay Dongare [email protected] 8087776107 10 Raigarh Alibag Ambepur Pranit Ramesh Patil 9823531575 11 Raigarh Alibag Awas Rohit Ashok Bhivande [email protected] 7798997398 12 Raigarh Alibag Bamangaon Rashmi Gajanan Patil [email protected] 9146992181 13 Raigarh Alibag Bamangaon NITESH VISHWANATH PATIL 9657260535 14 Raigarh Alibag Belkade Sanjeev Shrikant Kantak 9579327202 15 Raigarh Alibag Beloshi Santosh Namdev Nirgude [email protected] 8983604448 16 Raigarh Alibag BELOSHI KAILAS BALARAM ZAVARE 9272637673 17 Raigarh Alibag Chaul Sampada Sudhakar Pilankar [email protected] 9921552368 18 Raigarh Alibag Chaul VINANTI ANKUSH GHARAT 9011993519 19 Raigarh Alibag Chaul Santosh Nathuram Kaskar 9226375555 20 Raigarh Alibag Chendhre pritam umesh patil [email protected] 9665896465 21 Raigarh Alibag Chendhre Sudhir Krishnarao Babhulkar -

Dharamtar Port

Dharamtar Port Contents Management Reports Financial Statements 4 Notice 24 Independent Auditors' report 8 Directors' Report 34 Standalone Balance Sheet 35 Standalone Statement of Profit and Loss 36 Standalone Statement of Changes in Equity 37 Standalone Statement of Cash Flow 39 Notes Forward-looking statement In this Annual Report, we have disclosed forward looking information to enable the investors to comprehend our prospects and take informed investment decisions. This report and other statements – written and oral – that we periodically make, contain forward- looking statements that set out anticipated results based on the management’s plans and assumptions. We have tried wherever possible to identify such statements by using words such as ‘anticipates’, ‘estimates’, ‘expects’, ‘projects’, ‘intends’, ‘plans’, ‘believes’ and words of similar substance in connection with any discussion of future performance. We cannot guarantee that these forward-looking statements will be realised, although we believe, we have been prudent in our assumptions. The achievement of results is subject to risks, uncertainties and inaccurate assumptions. Should known or unknown risks or uncertainties materialise, or should underlying assumptions prove inaccurate, our actual results could vary materially from those anticipated, estimated or projected. Readers should bear this in mind. We undertake no obligation to publicly update any forward-looking statements, whether as a result of new information, future events or otherwise. FY20 Performance highlights Standalone J 19,385.78 LAKHS J 16,428.62 LAKHS GROSS TURNOVER NET TURNOVER J 10,521.61 LAKHS J5,572.28 LAKHS EBITDA PBT J7,800.97 LAKHS J4,976.19 LAKHS CASH PROFIT PAT CORPORATE INFORMATION Board of Directors MR. -

Jurisdiction Raigad Alibag.Pdf

CNTVTINNT JURISDICTION 'r ,r, .,r,:. ,,1, r r' .i T,. AIJBAGAIJBAG,. .rr.r,, ,:i .. L , ,., ...:i, . ,t .. , : L Court of Dirict and 1. Trial and Disposal of Session's cases and all Sessions Judge, Raigad-'special Cases arises in the area of Police Station Alibag Alibag, Mandawa Sagari, Revdanda, Poynad,, Pen, Wadkhal, Dadar Sagari, Nagothane, Murud 2. Appeals and Revision Petitions of rDecisions,/Orders passed by Adhoc-District, 'Magistrate, Raigad-Alibag, Chief Judicial, Magistrate, Raigad-Alibag, Judicial Magistrate of Sub-Division Alibag Pen and Murud. 3. Revision Petitions against Decisions,/Orders under Cr.P.C. Passed by Sub-Divisional Magistrate,/Additional District Magistrate of Sub- Division Alibag, Pen and Murud. Bail Application matters in the area of Police ,Station'4. Alibag, Mandawa Sagari, Revdanda, Poynad, Pen, Wadkhal, Dadar Sagari, Nagothane, Murud. 5. Application filled under section 408 Cr.P.C. 2 Court of District Judge- 1. Uearing & Disposal of all cases tr"rrsferred' 1 and Additional from District Coun. Session Judge, Raigad- Alibag 2. Trial & Disposal of cases relating to. M.O.C.C.A., E.C. Act., M.P.I.D. and case filed by C.B.I. under anti-corruption and N.D.P.S. arises iin the area of Police Station Alibag,r gryg6, Mandawa :Sagari, Revdanda, Poynad, Pen, Wadkhal, DadarDadar: . .:"l1t'Nagothane'*ulo:'Sagari, Nagothane, Murud. 3 Court of^^. District Judge- 1. Hearing A Oisposal oi all cases transferred 2 and Assistant Session from District Court. Judge, Raigad-Alibag 4 Coun of Adhoc District l. Hearing & Disposal of all cases transferred, Judge-1 and Assistant,from District Court. -

Press Release JSW Dharamtar Port Private Limited

Press Release JSW Dharamtar Port Private Limited January 28, 2020 Ratings Facilities Amount Rating1 Rating Action (Rs. crore) Long Term Bank Facilities 250.00 CARE A+; Stable Revised from CARE AA-; Stable (Term Loan) (Reduced from Rs.330 (Single A Plus; (Double A Minus; crore) Outlook: Stable) Outlook: Stable) Long Term Bank Facilities 39.00 CARE A; Stable Revised from CARE A+; Stable (Sub-ordinated debt) (Reduced from Rs.75 (Single A; (Single A Plus; crore) Outlook: Stable) Outlook: Stable) Long Term Bank Facilities 30.00 CARE A+; Stable Revised from CARE AA-; Stable (Non-Fund Based- LC/BG) (Single A Plus; (Double A Minus; Outlook: Stable) Outlook: Stable) Short Term Bank Facilities 5.00 CARE A1+ Reaffirmed (Non-Fund Based- LC/BG) (A one Plus) Short Term Bank Facilities 15.00 CARE A1+ Assigned (Fund Based-OD) (A one Plus) Total facilities 339.00 (Rupees three hundred and thirty nine crore only) Details of instruments/facilities in Annexure-1 Detailed Rationale & Key Rating Drivers The revision in the long term rating assigned to the bank facilities of JSW Dharamtar Port Private Limited (JSWDPL) takes into account significant capital expenditure plans of the parent, JSW Infrastructure Limited (JSWIL) which is envisaged to be executed over the next 4-5 years and is expected to result in significant deterioration in the capital structure going forward as a result of additional debt to be availed for executing the same. Furthermore, JSWIL is also undertaking expansion at existing ports primarily to cater to increased steel requirements of JSW Steel Limited (JSWSL) and two green-field projects which are yet to be fully operational. -

Maharashtra State Finance Corporation (MSFC) United India Building, 1St Floor, Sir P.M.Road, Fort Mumbai-01

108th Meeting of SEIAA, Maharashtra Venue: Maharashtra State Finance Corporation (MSFC) United India Building, 1st Floor, Sir P.M.Road, Fort Mumbai-01 Date: 07.04.2017 Time: 10.00Am Please Submit the online application on www.ecmpcb.in website. Sr Name of Project No Date: 07.04.2017 Timing: 10.00 am to 1.30pm 1. Proposed amendment in Environmental & CRZ clearance granted for proposal of Inland Water Transport along East Coast to Mumbai by MMB 2. Proposed setting up of Terminal Building cum Recreation Centre for Ro-Ro Pax Operation at Ferry Wharf Mumbai by MBPT 3. Proposed Biodiversity Park at SaketMaujeMajiwada, Dist. Thane by Social Forestry Department, Thane District Collector 4. Providing and laying 300mm, 350mm & 400 mm dia RC NP3 class pipe sewer along kadeshwari road, Panglewadi Road, Bandra (West) in H/ West Ward, Mumbai by MCGM 5. Proposed construction of Ferry Jetty at Marve, Mumbai Suburban by MMB 6. Proposed construction of new bridge across Varsave Creek, Vasai along NH-8 by M/s National Highways Authority of India 7. Proposed construction of Minor Fishing Harbour at Navgaon - Thal, Tal. Alibag, Dist. Raigad by M/s Rashtriya Chemicals & Fertilizers Limited 8. Proposed Sindhudurg Coastal Circuit project at Tarkarli, NivatiKilla, Mithbab, Vijaydurg, Sagareshwar, Tondavli, Mochemad, Shiroda and Devgad under the SwadeshDarshan Scheme by Directorate of Tourism, GoM 9. Proposed construction of 30 M W D.P. Road with drains from NH-4 to Hospital reservation on plot bearing S. No. 15B v(pt), 40A(pt), 51A(pt), 53 (pt), 54 (pt), 55(pt), 66A(pt), 67(pt). -

Rapid Environment Impact Assessment Report

KIHIM RESORT Rapid Environment Impact Assessment Report M R . GAUTAM CHAND Project Proponent +91 98203 39444 [email protected] MOEFCC Proposal No.:IA/MH/MIS/100354/2019 18 A p r i l , 2019 Project Proponent: Rapid Environment Impact Assessment Report for CRZ MCZMA Ref. No.: Mr. Gautam Chand (Individual) Proposed Construction of Holiday Resort CRZ-2015/CR-167/TC-4 Village: Kihim, Taluka: Alibag, District: Raigad, MOEFCC Proposal No.: State: Maharashtra, PIN: 402208, Country: India IA/MH/MIS/100354/2019 CONTENTS Annexure A from MOEFCC CRZ Meeting Agenda template 6 Compliance on Guidelines for Development of Beach Resorts or Hotels 10 CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION 13 1.1 Preamble 13 1.2 Objective and Scope of study 13 1.3 The Steps of EIA 13 1.4 Methodology adopted for EIA 14 1.5 Project Background 15 1.6 Structure of the EIA Report 19 CHAPTER 2: PROJECT DESCRIPTION 20 2.1 Introduction 20 2.2 Description of the Site 20 2.3 Site Selection 21 2.4 Project Implementation and Cost 21 2.5 Perspective view 22 2.5.1 Area Statement 24 2.6 Basic Requirement of the Project 24 2.6.1 Land Requirement 24 2.6.2 Water Requirement 25 2.6.3 Fuel Requirement 26 2.6.4 Power Requirement 26 2.6.5 Construction / Building Material Requirement 29 2.7 Infrastructure Requirement related to Environmental Parameters 29 2.7.1 Waste water Treatment 29 2.7.1.1 Sewage Quantity 29 2.7.1.2 Sewage Treatment Plant 30 2.7.2 Rain Water Harvesting & Strom Water Drainage 30 2.7.3 Solid Waste Management 31 2.7.4 Fire Fighting 33 2.7.5 Landscape 33 2.7.6 Project Cost 33 CHAPTER 3: DESCRIPTION -

Company Profile

COMPANY PROFILE Rev. 03 /27.01.2018 COMPANY PROFILE Marine Frontiers is the name synonymous with the construction of aluminium vessels including commercial boats, defense boats, wind farm support vessels helicopter decks and floating jetty structures. With a wide range of tried and proven vessels in service throughout the world, the name- ‘Marine Frontiers’ bears a seal of unshakeable trust. The company was established in 2002 to provide a world class aluminium shipbuilding company with repair & maintenance yard for vessels up to 500 Tonnes and design & construction of marina pontoon systems for both the domestic and exports markets. The water front boat yard is located at: Dharamtar, Dist. Raigad which is 100 Kms. by road from Mumbai & 12NM from iconic Gateway of India. The yard has 100% in house back up for the manufacturing, refit, repairs & servicing of aluminum vessels, floating structures, marine engineering and helicopter decks for customer satisfaction. Registrations Company has fulfilled all the statutory and legal requirements including – - Factory License, - SSI Registration, - GST Registration, - Excise Registration - IEC Code - PAN Account - QMS ISO 9001:2008 Certification with DNV.GL - CRISIL Rating Certificate 1 | P a g e QUALITY POLICY We, at Marine Frontiers Pvt. Ltd. are committed to provide Quality Products and Services in the vision to be the ‘Leading Aluminium Boat Yard in India’ by fulfilling the needs and expectations of our Customers and satisfying the requirements of ISO 9001:2008. Company is also committed for continual improvement in products and services, relevant processes and procedures by establishing, implementing, maintaining and reviewing Quality Management System. Nitin Doshi Chief Executive Officer 2 | P a g e ENVIRONMENTAL POLICY Marine Frontiers, a leading aluminium boatyard is committed to environmental protection in line with the requirements of ISO 14001:2004. -

Underwater-Coastal Diversity of Edible Bivalve of Revas (Raigad), Coast Of

Journal of Entomology and Zoology Studies 2016; 4(4): 722-725 E-ISSN: 2320-7078 P-ISSN: 2349-6800 Underwater-coastal diversity of edible bivalve of JEZS 2016; 4(4): 722-725 © 2016 JEZS Revas (Raigad), coast of India Received: 08-05-2016 Accepted: 09-06-2016 Sunil N Khade Sunil N Khade Department of Zoology P.N. College, Pusad, District Abstract Yavatmal, Maharashtra, India. Underwater and coastal diversity of edible bivalve molluscs was studied twice in each season monsoon, post monsoon, winter and summer July 2010 to June 2011 with the help of SCUBA diving by DM. At each locality diversity and number of species were collected from Nagaon, Kegaon, open sea and local markets too. The selected localities of Raigad district coast is a wide chance of research to further explore both on the possibility of commercial value and ecosystem conservation. Keywords: Diversity, edible bivalve, Revas, coast of India 1. Introduction The marine bivalve molluscs resources of India clams are widely distributed and abundant, the form subsistence fisheries all along the Indian coast and fished by men, women and children from the intertidal region to about 4m depth, they are handpicked. These organisms usually inhabit bottom substrates for at least part of their life cycle. Several species of Veneridae family clams that occur along the coast of Maharashtra Placenta placenta one is important point of view as food. It contributes about 80% to the total production of clams landed annually mainly from Kalbadevi (Shirgaon creek) and (Kajali Bhatye creek) estuaries along Ratnagiri coast, Maharashtra [1]. Bivalve provides an important source of protein for human besides fish, it can be found in many parts of the world such as marine, brackish, fresh and terrestrial areas.