Exploring Honeyguide– Human Mutualism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

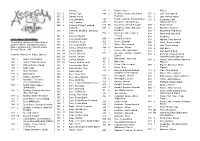

List I: Sasol, Third Edition This Bird List Conforms to Sasol Birds of Southern

Canary) 172 1 Falcon, Lanner Plover) 872 2 Canary, Cape 840 2 Firefinch, African (Bluebilled 507 2 Lark, Red-capped 873 2 Canary, Forest Firefinch) 494 1 Lark, Rufous-naped 595 3 Chat, Anteating 732 1 Fiscal, Common (Fiscal Shrike) 727 2 Longclaw, Cape 589 2 Chat, Familiar 690 1 Flycatcher, African Dusky (Orangethroated) 664 2 Cisticola, Zitting (Fantailed 710 1M Flycatcher, African Paradise 529 1 Martin, Rock Cisticola) 691 3 Flycatcher, Ashy (Bluegrey 226 1 Moorhen, Common 593 1 Cliff-Chat, Mocking - (Mocking Flycather) 426 1 Mousebird, Red-faced Chat) 708 2 Flycatcher, Blue-mantled 424 1 Mousebird, Speckled 846 2 Common Waxbill Crested 681 1 Neddicky List I: Sasol, Third Edition 228 1 Coot, Red-knobbed 698 1 Flycatcher, Fiscal 405 2 Nightjar, Fiery-necked This bird list conforms to Sasol Birds of 58 1 Cormorant, Reed 102 1 Goose, Egyptian 545 1 Oriole, Black-headed Southern Africa, Third Edition (2002). 391 2 Coucal, Burchell's 116 2 Goose, Spur-winged 394 2 Owl, African Wood Names in brackets are from the Sasol 384 3 Cuckoo, African Emerald 160 2 Goshawk, African 392 2 Owl, Barn Second Edition (1997). 378 1M Cuckoo, Black 8 1 Grebe, Little (Dabchick) 401 2 Owl, Spotted Eagle 572 1 Greenbul, Sombre (Sombre Columns: Roberts Nr, Status, Species 386 2M Cuckoo, Diderick 805 2 Petronia, Yellow-throated 382 2M Cuckoo, Jacobin Bulbul) (Yellowthroated Sparrow) 645 1 Apalis, Bar-throated 385 1M Cuckoo, Klaas's 203 2 Guineafowl, Helmeted 350 2 Pigeon, African Olive (Rameron 648 1 Apalis, Yellow-breasted 377 2M Cuckoo, Red-chested 81 2 Hamerkop -

Bird Checklists of the World Country Or Region: Ghana

Avibase Page 1of 24 Col Location Date Start time Duration Distance Avibase - Bird Checklists of the World 1 Country or region: Ghana 2 Number of species: 773 3 Number of endemics: 0 4 Number of breeding endemics: 0 5 Number of globally threatened species: 26 6 Number of extinct species: 0 7 Number of introduced species: 1 8 Date last reviewed: 2019-11-10 9 10 Recommended citation: Lepage, D. 2021. Checklist of the birds of Ghana. Avibase, the world bird database. Retrieved from .https://avibase.bsc-eoc.org/checklist.jsp?lang=EN®ion=gh [26/09/2021]. Make your observations count! Submit your data to ebird. -

Birding Tour to Ghana Specializing on Upper Guinea Forest 12–26 January 2018

Birding Tour to Ghana Specializing on Upper Guinea Forest 12–26 January 2018 Chocolate-backed Kingfisher, Ankasa Resource Reserve (Dan Casey photo) Participants: Jim Brown (Missoula, MT) Dan Casey (Billings and Somers, MT) Steve Feiner (Portland, OR) Bob & Carolyn Jones (Billings, MT) Diane Kook (Bend, OR) Judy Meredith (Bend, OR) Leaders: Paul Mensah, Jackson Owusu, & Jeff Marks Prepared by Jeff Marks Executive Director, Montana Bird Advocacy Birding Ghana, Montana Bird Advocacy, January 2018, Page 1 Tour Summary Our trip spanned latitudes from about 5° to 9.5°N and longitudes from about 3°W to the prime meridian. Weather was characterized by high cloud cover and haze, in part from Harmattan winds that blow from the northeast and carry particulates from the Sahara Desert. Temperatures were relatively pleasant as a result, and precipitation was almost nonexistent. Everyone stayed healthy, the AC on the bus functioned perfectly, the tropical fruits (i.e., bananas, mangos, papayas, and pineapples) that Paul and Jackson obtained from roadside sellers were exquisite and perfectly ripe, the meals and lodgings were passable, and the jokes from Jeff tolerable, for the most part. We detected 380 species of birds, including some that were heard but not seen. We did especially well with kingfishers, bee-eaters, greenbuls, and sunbirds. We observed 28 species of diurnal raptors, which is not a large number for this part of the world, but everyone was happy with the wonderful looks we obtained of species such as African Harrier-Hawk, African Cuckoo-Hawk, Hooded Vulture, White-headed Vulture, Bat Hawk (pair at nest!), Long-tailed Hawk, Red-chested Goshawk, Grasshopper Buzzard, African Hobby, and Lanner Falcon. -

2017 Namibia, Botswana & Victoria Falls Species List

Eagle-Eye Tours Namibia, Okavango and Victoria Falls November 2017 Bird List Status: NT = Near-threatened, VU = Vulnerable, EN = Endangered, CR = Critically Endangered Common Name Scientific Name Trip STRUTHIONIFORMES Ostriches Struthionidae Common Ostrich Struthio camelus 1 ANSERIFORMES Ducks, Geese and Swans Anatidae White-faced Whistling Duck Dendrocygna viduata 1 Spur-winged Goose Plectropterus gambensis 1 Knob-billed Duck Sarkidiornis melanotos 1 Egyptian Goose Alopochen aegyptiaca 1 African Pygmy Goose Nettapus auritus 1 Hottentot Teal Spatula hottentota 1 Cape Teal Anas capensis 1 Red-billed Teal Anas erythrorhyncha 1 GALLIFORMES Guineafowl Numididae Helmeted Guineafowl Numida meleagris 1 Pheasants and allies Phasianidae Crested Francolin Dendroperdix sephaena 1 Hartlaub's Spurfowl Pternistis hartlaubi H Red-billed Spurfowl Pternistis adspersus 1 Red-necked Spurfowl Pternistis afer 1 Swainson's Spurfowl Pternistis swainsonii 1 Natal Spurfowl Pternistis natalensis 1 PODICIPEDIFORMES Grebes Podicipedidae Little Grebe Tachybaptus ruficollis 1 Black-necked Grebe Podiceps nigricollis 1 PHOENICOPTERIFORMES Flamingos Phoenicopteridae Greater Flamingo Phoenicopterus roseus 1 Lesser Flamingo - NT Phoeniconaias minor 1 CICONIIFORMES Storks Ciconiidae Yellow-billed Stork Mycteria ibis 1 Eagle-Eye Tours African Openbill Anastomus lamelligerus 1 Woolly-necked Stork Ciconia episcopus 1 Marabou Stork Leptoptilos crumenifer 1 PELECANIFORMES Ibises, Spoonbills Threskiornithidae African Sacred Ibis Threskiornis aethiopicus 1 Hadada Ibis Bostrychia -

Kenyan Birding & Animal Safari Organized by Detroit Audubon and Silent Fliers of Kenya July 8Th to July 23Rd, 2019

Kenyan Birding & Animal Safari Organized by Detroit Audubon and Silent Fliers of Kenya July 8th to July 23rd, 2019 Kenya is a global biodiversity “hotspot”; however, it is not only famous for extraordinary viewing of charismatic megafauna (like elephants, lions, rhinos, hippos, cheetahs, leopards, giraffes, etc.), but it is also world-renowned as a bird watcher’s paradise. Located in the Rift Valley of East Africa, Kenya hosts 1054 species of birds--60% of the entire African birdlife--which are distributed in the most varied of habitats, ranging from tropical savannah and dry volcanic- shaped valleys to freshwater and brackish lakes to montane and rain forests. When added to the amazing bird life, the beauty of the volcanic and lava- sculpted landscapes in combination with the incredible concentration of iconic megafauna, the experience is truly breathtaking--that the Africa of movies (“Out of Africa”), books (“Born Free”) and documentaries (“For the Love of Elephants”) is right here in East Africa’s Great Rift Valley with its unparalleled diversity of iconic wildlife and equatorially-located ecosystems. Kenya is truly the destination of choice for the birdwatcher and naturalist. Karibu (“Welcome to”) Kenya! 1 Itinerary: Day 1: Arrival in Nairobi. Our guide will meet you at the airport and transfer you to your hotel. Overnight stay in Nairobi. Day 2: After an early breakfast, we will embark on a full day exploration of Nairobi National Park--Kenya’s first National Park. This “urban park,” located adjacent to one of Africa’s most populous cities, allows for the possibility of seeing the following species of birds; Olivaceous and Willow Warbler, African Water Rail, Wood Sandpiper, Great Egret, Red-backed and Lesser Grey Shrike, Rosy-breasted and Pangani Longclaw, Yellow-crowned Bishop, Jackson’s Widowbird, Saddle-billed Stork, Cardinal Quelea, Black-crowned Night- heron, Martial Eagle and several species of Cisticolas, in addition to many other unique species. -

Leptosomiformes ~ Trogoniformes ~ Bucerotiformes ~ Piciformes

Birds of the World part 6 Afroaves The core landbirds originating in Africa TELLURAVES: AFROAVES – core landbirds originating in Africa (8 orders) • ORDER ACCIPITRIFORMES – hawks and allies (4 families, 265 species) – Family Cathartidae – New World vultures (7 species) – Family Sagittariidae – secretarybird (1 species) – Family Pandionidae – ospreys (2 species) – Family Accipitridae – kites, hawks, and eagles (255 species) • ORDER STRIGIFORMES – owls (2 families, 241 species) – Family Tytonidae – barn owls (19 species) – Family Strigidae – owls (222 species) • ORDER COLIIFORMES (1 family, 6 species) – Family Coliidae – mousebirds (6 species) • ORDER LEPTOSOMIFORMES (1 family, 1 species) – Family Leptosomidae – cuckoo-roller (1 species) • ORDER TROGONIFORMES (1 family, 43 species) – Family Trogonidae – trogons (43 species) • ORDER BUCEROTIFORMES – hornbills and hoopoes (4 families, 74 species) – Family Upupidae – hoopoes (4 species) – Family Phoeniculidae – wood hoopoes (9 species) – Family Bucorvidae – ground hornbills (2 species) – Family Bucerotidae – hornbills (59 species) • ORDER PICIFORMES – woodpeckers and allies (9 families, 443 species) – Family Galbulidae – jacamars (18 species) – Family Bucconidae – puffbirds (37 species) – Family Capitonidae – New World barbets (15 species) – Family Semnornithidae – toucan barbets (2 species) – Family Ramphastidae – toucans (46 species) – Family Megalaimidae – Asian barbets (32 species) – Family Lybiidae – African barbets (42 species) – Family Indicatoridae – honeyguides (17 species) – Family -

The Honeyguide

THE HONEYGUIDE (Children’s Story/Parable) Gary B. Swanson Associate Director General Conference Sabbath School and Personal Ministries “‘I tell you the truth, whoever hears my word and believes him who sent me has eternal life and will not be condemned; he has crossed over from death to life’” (John 5:24 NIV). In northern Kenya a nomadic tribe of people, the Borans, have learned to communicate in a crude way with a species of birds, known as honeyguides. These birds first draw the attention of humans by swooping close to them, hopping restlessly from branch to branch nearby, and making a persistent call. When the humans approach, the bird disappears over the treetops, but reappears after about 20 minutes to call again and wait for them to proceed further. The Borans follow the birds, all the while whistling, banging sticks together, or talking loudly. This pattern is repeated till the bird and the human reach a beehive in an average of about three hours. Then the Borans enjoy the honey—a staple in their diet—and the honeyguides feast on bee larvae and wax from the honeycombs. Although accounts of this relationship between human and bird have been reported since the 1700s, biologists have only recently documented it. Researchers have found that if they leave the hive to which a bird has led them without breaking into it, the bird will guide them back again and again. This, in a way, is what Bible study does for a Christian. It repeatedly returns the reader to the real source of life, Jesus Christ. -

Bird Survey of South-Eastern Laikipia: Lolldaiga Ranch, Ole Naishu Ranch, Borana Ranch, and Mukogodo Forest Reserve

8 November 2015 Dear All, Recently Nigel Hunter and I went to stay with Tom Butynski on Lolldaiga Hills Ranch. Whilst there we were joined by Paul Benson, and Eleanor Monbiot for the 31st Oct, Chris Thouless joined us on 1st Nov in Mukogodo, and he and Caroline kindly put the three of us up at their house for the nights of 31st Oct and 1st Nov., and for both these dates we enjoyed the company of Lawrence, the bird-guide at Borana Lodge. For our full day on Lolldaiga on 2nd Nov., Paul spent the entire day with us. The more interesting observations follow, but this is far from the full list which exceeded 200 on Lolldaiga alone in spite of the relatively short time we were there. Best for now Brian BIRD SURVEY OF SOUTH-EASTERN LAIKIPIA: LOLLDAIGA RANCH, OLE NAISHU RANCH, BORANA RANCH, AND MUKOGODO FOREST RESERVE ITINERARY 30th Oct 2015 Drove Nairobi to Lolldaiga, birded as far as old Maize Paddock in late afternoon. 31st Oct Drove from TB house out through Ole Naishu Ranch and across Borana arriving at Mukogodo Forest in early afternoon. 1st Nov All day in Mukogodo Forest, and just 5 kilometres down the main descent road in afternoon. 2nd Nov All day on Borana, back across Ole Naishu to Lolldaiga. 3rd Nov All day outing on Lolldaiga to Black Rock, Ngainitu Kopje (North Gate), Sinyai Lugga, and evening near the Monument. 4th Nov Morning on descent road to Main Gate, Lolldaiga and forest along Timau River, leaving 11.15 AM for Nairobi. -

Notes on Honeyguides in Southeast Cape Province, South Africa

52 SK•AD,Honeyguides ofSoutheast CapeProvince t[AukJan. NOTES ON HONEYGUIDES IN SOUTHEAST CAPE PROVINCE, SOUTH AFRICA BY C. J. SKEAD Now that I am no longer living on a farm it seemsadvisable to collate what little data I have accumulatedon honeyguidesand add it to the scanty knowledgewe have of these birds, in this instance the LesserHoneyguide, Indicator minor minor, the Greater Honeyguide, Indicator indicator, and Wahlberg's Sharp-billed Honeyguide, Pro- dotiscusregulus regulus. The farm "Gameston" where these records were taken lies in the grass-and bush-coveredupper reachesof the Kariega River, 15 miles southwestof Grahamstown, Albany district, Southeast Cape Province, South Africa. This veld-type, known as "bontebosveld," spreads over a large part of the southeastcape. Although I have known the birds for many years the written recordscover a period of about five years. (1) THE LESSERHONEYGUIDE F.colog3.--This speciesprefers the scrub bushyeld and more open acaciaveld, sitting amongthe inner branchesof the trees and bushes but makingconspicuous flights in the openfrom one patch of bushto another. Status.--I have recordedthem in January, February, March, July, August,September, and December. This suggeststhey are resident and not migratory. They are very restlessbirds being seldomseen for more than an hour or so and, in my experience,usually one at a time, even when they parasitized a nest of Black-collared Barbers, Lybius torquatus,in our garden. But from July to September, 1949, two often consortedtogether, attracted, I think, by combs of honey protrudingfrom the gardenbee-hives. There were no barbetsin the garden then. Field Characters.--Thereare no striking features; their dull colora- tion is lightly offset by the golden sheen seen on the back when the light is good. -

Western Birds

WESTERN BIRDS Vol. 49, No. 4, 2018 Western Specialty: Golden-cheeked Woodpecker Second-cycle or third-cycle Herring Gull at Whiting, Indiana, on 25 January 2013. The inner three primaries on each wing of this bird appear fresher than the outer primaries. They may represent the second alternate plumage (see text). Photo by Desmond Sieburth of Los Angeles, California: Golden-cheeked Woodpecker (Melanerpes chrysogenys) San Blas, Nayarit, Mexico, 30 December 2016 Endemic to western mainland Mexico from Sinaloa south to Oaxaca, the Golden-cheeked Woodpecker comprises two well-differentiated subspecies. In the more northern Third-cycle (or possibly second-cycle) Herring Gull at New Buffalo, Michigan, on M. c. chrysogenys the hindcrown of both sexes is largely reddish with only a little 14 September 2014. Unlike the other birds illustrated on this issue’s back cover, in this yellow on the nape, whereas in the more southern M. c. flavinuchus the hindcrown is individual the pattern of the inner five primaries changes gradually from feather to uniformly yellow, contrasting sharply with the forehead (red in the male, grayish white feather, with no abrupt contrast. Otherwise this bird closely resembles the one on the in the female). The subspecies intergrade in Nayarit. Geographic variation in the outside back cover, although the prealternate molt of the other body and wing feathers Golden-cheeked Woodpecker has not been widely appreciated, perhaps because so many has not advanced as far. birders and ornithologists are familiar with the species from San Blas, in the center of Photos by Amar Ayyash the zone of intergradation. Volume 49, Number 4, 2018 The 42nd Annual Report of the California Bird Records Committee: 2016 Records Guy McCaskie, Stephen C. -

The Gambia in Style

The Gambia in Style Naturetrek Tour Report 7 - 14 December 2018 Broad-billed Roller Blue-breasted Kingfisher Western Red Colobus Little Bee-eater Report compiled by Duncan McNiven Images courtesy of Debbie Pain Naturetrek Mingledown Barn Wolf's Lane Chawton Alton Hampshire GU34 3HJ UK T: +44 (0)1962 733051 E: [email protected] W: www.naturetrek.co.uk Tour Report The Gambia in Style Tour participants: Duncan McNiven and Debbie Pain (leaders) plus local guides and 12 Naturetrek clients Day 1 Friday 7th December London Gatwick to Mandina Lodge We all met up at Gatwick Airport for our mid-morning Titan Airways flight to Banjul, the capital of Gambia. Our flight was slightly delayed due to inclement weather but soon enough we were on our way south, leaving behind the mountains and plains of southern Europe and crossing the vast aridness of the Sahara Desert. Eventually, the landscape below us became greener and lusher as we crossed in to Senegal and entered the Guinea Savannah biome. By the time we touched down in Banjul it was already early evening and the light was beginning to wane. Duncan and Debbie were there to meet and greet us and help with acquiring the small amount of local currency we would require for our holiday and in no time at all we were aboard our bus for our short journey to Mandina Lodge. Less than an hour later we were sat under the twinkling fairy lights of the Mandina reception area whilst our gracious host Linda welcomed us and gave us the briefest of briefings before we were all shown to our luxurious lodges nestled amongst the mangroves and forest trees lining the river. -

Adult Brood Parasites Feeding Nestlings and Fledglings of Their Own Species: a Review

J. Field Ornithol., 69(3):364-375 ADULT BROOD PARASITES FEEDING NESTLINGS AND FLEDGLINGS OF THEIR OWN SPECIES: A REVIEW JANICEC. LORENZANAAND SPENCER G. SEALY Departmentof Zoology Universityof Manitoba Winnipeg,Manitoba R3T 2N2 Canada Abstract.--We summarized 40 reports of nine speciesof brood parasitesfeeding young of their own species.These observationssuggest that the propensityto provisionyoung hasnot been lost entirely in brood parasitesdespite the belief that brood parasiticadults abandon their offspringat the time of laying.The hypothesisthat speciesthat participatein courtship feeding are more likely to provisionyoung was not supported:provisioning of young has been observedin two speciesof brood parasitesthat do not courtshipfeed. The function of this provisioningis unknown, but we suggestit may be: (1) a non-adaptivevestigial behavior or (2) an adaptation to ensure adequatecare of parasiticyoung. The former is more likely the case.Further studiesare required to determinewhether parasiticadults commonly feed their genetic offspring. ADULTOS DE AVES PARAS•TICASALIMENTANDO PICHONES Y VOLANTONES DE SU PROPIA ESPECIE: UNA REVISION Sinopsis.--Resumimos40 informes de nueve especiesde avesparasiticas que alimenaron a pichonesde su propia especie.Las observacionessugieren que la propensividadde alimentar a los pichonesno ha sido totalmente perdida en las avesparasiticas, no empecea la creencia de que los parasiticosabandonan su progenie al momento de poner los huevos.La hipttesis de que las especiesque participan en cortejo de alimentacitn, son milspropensas a alimentar los pichonesno tuvo apoyo.Las observacionesde alimentacitn a pichonesse han hecho en dos especiesparasiticas cuyo cortejo no incluye la alimentacitn de la pareja. La funcitn de proveer alimento se desconoce.No obstante,sugerimos que pueda ser: 1) una conducta vestigialno adaptativa,o 2) una adaptacitn parc asegurarel cuidado adecuadode los pi- chonesparasiticos.