History in the Making: Behind the Scenes at Canelo–Jacobs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How I Got the Job at Adidas Combat Gear When I Initially Heard About Adidas Combat Sports USA, It Was Through My Friend Jeff

How I Got The Job at Adidas Combat Gear When I initially heard about adidas Combat Sports USA, it was through my friend Jeff Chu, a local photographer and videographer. He had taken on a job as part of his freelance career and since I had recently been laid off from a magazine I was working for, decided to tag along. "It's all about the networking in this business," Jeff said. And it is. Because I tagged along, I met ACS President Scott Viscomi and five months later had a job as a blog editor of this website. Before Scott had taken on the task of creating some of the best gear in the combat sports industry, the adidas logo had entered the realm of jiu-jitsu competition when I was only a white belt years ago. Or at least that's the first time I had seen it. The gis that were created then were more cut for a judo competitor, with short sleeves and stiff material. It wasn't pliable, equipt to move along with a jiu-jitsu athlete while playing spider guard or butterfly guard, or passing guard and taking the back. Somewhere along the line, before I ever saw an adidas gi again, the design changed. It was in new hands. As I walked into Church Street Boxing in Lower Manhattan, it was a lot different from the jiu-jitsu academies I'd trained in for six years. In the middle of the main room was a raised boxing ring and all around it were walls covered in mirrors and old photographs and fight posters. -

World Boxing Association

WORLD BOXING ASSOCIATION GILBERTO MENDOZA PRESIDENT OFFICIAL RATINGS AS OF AUGUST 2011 th th Based on results held from August 05 To August 29 , 2011 CHAIRMAN MEMBERS Edificio Ocean Business Plaza, Ave. JOSE OLIVER GOMEZ E-mail: [email protected] Aquilino de la Guardia con Calle 47, BARTOLOME TORRALBA (SPAIN) Oficina 1405, Piso 14 JOSE EMILIO GRAGLIA (A RGENTINA) Cdad. de Panamá, Panamá VICE CHAIRMAN ALAN KIM (KOREA) Phone: + (507) 340-6425 GEORG E MARTINEZ E-mail: [email protected] Web Site: www.wbanews.com HEAVYWEIGHT (Over 200 Lbs / 90.71 Kgs) CRUISERWEIGHT (200 Lbs / 90.71 Kgs) LIGHT HEAVYWEIGHT (175 Lbs / 79.38 Kgs) SUPER CHAMPION: WLADIMIR KLITSCHKO UKR World Champion: GUILLERMO JONES PAN World Cham pion: BEIBU T SHUMENOV KAZ World Champion: Won Title: 09- 27-08 Won Title: 01-29- 10 ALEXANDER POVETKIN RUS Last Mandatory: 10- 02-10 Last Mandatory: 07-23- 10 Won Title: 08-27-11 Last Defense: 10-02-10 Last Defense: 07-29-11 Last Mandatory: INTERIM CHAMPION: YOAN PABLO HERNANDEZ CUB Last Defense: IBF: STEVE CUNNINGHAM - WBO: MARCO HUCK WBC: BERNARD HOPKINS - IBF: TAVORIS CLOUD WBC: KRZYSZTOF WLODARCZYK WBC: VITALY KLITSCHKO - IBF:WLADIMIR KLITSCHKO WBO: NATHAN CLEVERLY WBO : WLADIMIR KLITSCHKO 1. HASIM RAHMAN USA 1. LATEEF KAYODE (NABA) NIG 1. GABRIEL CAMPILLO (OC) SPA 2. DAVID HAYE U.K. 2. PAWEL KOLODZIEJ (WBA INT) POL 2. GAYRAT AMEDOV (WB A INT) UZB 3. ROBERT HELENIUS (WBA I/C) FIN 3. OLA AFOLABI U.K. 3. DAWID KOSTECKY (WBA I/C) POL 4. ALEXANDER USTINO V (EBA) RUS 4. STEVE HERELIUS FRA 4. -

WORLD BOXING ASSOCIATION GILBERTO JESUS MENDOZA PRESIDENT OFFICIAL RATINGS AS of AUGUST Based on Results Held from 01St to August 31St, 2018

2018 Ocean Business Plaza Building, Av. Aquilino de la Guardia and 47 St., 14th Floor, Office 1405 Panama City, Panama Phone: +507 203-7681 www.wbaboxing.com WORLD BOXING ASSOCIATION GILBERTO JESUS MENDOZA PRESIDENT OFFICIAL RATINGS AS OF AUGUST Based on results held from 01st to August 31st, 2018 CHAIRMAN VICE CHAIRMAN MIGUEL PRADO SANCHEZ - PANAMA GUSTAVO PADILLA - PANAMA [email protected] [email protected] The WBA President Gilberto Jesus Mendoza has been acting as interim MEMBERS ranking director for the compilation of this ranking. The current GEORGE MARTINEZ - CANADA director Miguel Prado is on a leave of absence for medical reasons. JOSE EMILIO GRAGLIA - ARGENTINA MARIANA BORISOVA - BULGARIA Over 200 Lbs / 200 Lbs / 175 Lbs / HEAVYWEIGHT CRUISERWEIGHT LIGHT HEAVYWEIGHT Over 90.71 Kgs 90.71 Kgs 79.38 Kgs WBA SUPER CHAMPION: ANTHONY JOSHUA GBR WBA SUPER CHAMPION: OLEKSANDR USYK UKR WORLD CHAMPION: MANUEL CHARR SYR CHAMPION IN RECESS: DENIS LEBEDEV RUS WORLD CHAMPION: DMITRY BIVOL RUS WBC: DEONTAY WILDER WORLD CHAMPION: BEIBUT SHUMENOV KAZ WBC: ADONIS STEVENSON IBF: ANTHONY JOSHUA WBO: ANTHONY JOSHUA WBC: OLEKSANDR USYK IBF: ARTUR BETERBIEV WBO: ELEIDER ALVAREZ 1. TREVOR BRYAN INTERIM CHAMP USA IBF: OLEKSANDR USYK WBO: OLEKSANDR USYK 1. BADOU JACK SWE 2. ALEXANDER POVETKIN I/C RUS 1. ARSEN GOULAMIRIAN INTERIM CHAMP ARM 2. MARCUS BROWNE USA 3. FRES OQUENDO PUR 2. MAKSIM VLASOV RUS 3. KARO MURAT ARM 4. JARRELL MILLER USA 3. KRZYSZTOF GLOWACKI POL 4. SULLIVAN BARRERA CUB 5. DILLIAN WHYTE JAM 4. MATEUSZ MASTERNAK POL 5. SHEFAT ISUFI SRB 6. DERECK CHISORA INT GBR 5. RUSLAN FAYFER RUS 6. -

World Boxing Council Ratings

WORLD BOXING COUNCIL R A T I N G S RATINGS AS OF SEPTEMBER - 2018 / CLASIFICACIONES DEL MES DE SEPTIEMBRE - 2018 WORLD BOXING COUNCIL / CONSEJO MUNDIAL DE BOXEO COMITE DE CLASIFICACIONES / RATINGS COMMITTEE WBC Adress: Riobamba # 835, Col. Lindavista 07300 – CDMX, México Telephones: (525) 5119-5274 / 5119-5276 – Fax (525) 5119-5293 E-mail: [email protected] RATINGS RATINGS AS OF SEPTEMBER - 2018 / CLASIFICACIONES DEL MES DE SEPTIEMBRE - 2018 HEAVYWEIGHT (+200 - +90.71) CHAMPION: DEONTAY WILDER (US) EMERITUS CHAMPION: VITALI KLITSCHKO (UKRAINE) WON TITLE: January 17, 2015 LAST DEFENCE: March 3, 2018 LAST COMPULSORY: November 4, 2017 WBC SILVER CHAMPION: Dillian Whyte (Jamaica/GB) WBC INT. CHAMPION: VACANT WBA CHAMPION: Anthony Joshua (GB) IBF CHAMPION: Anthony Joshua (GB) WBO CHAMPION: Anthony Joshua (GB) Contenders: WBO CHAMPION: Joseph Parker (New Zealand) WBO CHAMPION:WBO CHAMPION: Joseph Parker Joseph (New Parker Zealand) (New Zealand) 1 Dillian Whyte (Jamaica/GB) SILVER Note: all boxers rated within the top 15 are 2 Luis Ortiz (Cuba) required to register with the WBC Clean 3 Tyson Fury (GB) * CBP/P Boxing Program at: www.wbcboxing.com 4 Dominic Breazeale (US) Continental Federations Champions: 5 Tony Bellew (GB) ABCO: 6 Joseph Parker (New Zealand) ABU: Tshibuabua Kalonga (Congo/Germany) BBBofC: Hughie Fury (GB) 7 Agit Kabayel (Germany) EBU CISBB: 8 Dereck Chisora (GB) EBU: Agit Kabayel (Germany) 9 Charles Martin (US) FECARBOX: 10 FECONSUR: Adam Kownacki (US) NABF: Oscar Rivas (Colombia/Canada) 11 Oscar Rivas (Colombia/Canada) NABF OPBF: Kyotaro Fujimoto (Japan) 12 Hughie Fury (GB) BBB C 13 Bryant Jennings (US) Affiliated Titles Champions: Commonwealth: Joe Joyce (GB) 14 Andy Ruiz Jr. -

HEAVYWEIGHT (OVER 200 LBS) CH Wladimir Klitschko UKR 1 Wladimir

HEAVYWEIGHT (OVER 200 LBS) CRUISERWEIGHT (200 LBS) LT. HEAVYWEIGHT (175 LBS) S. MIDDLEWEIGHT (168 LBS) CH Wladimir Klitschko UKR CH VACANT CH Tavoris Cloud USA CH Lucian Bute CAN 1 Wladimir Klitschko UKR 1 NOT RATED 1 Tavoris Cloud USA 1 Lucian Bute CAN 2 Alexander Povetkin RUS 2 Steve Cunningham USA 2 NOT RATED 2 Librado Andrade USA 3 NOT RATED 3 NOT RATED 3 NOT RATED 3 NOT RATED 4 Eddie Chambers USA 4 Matt Godfrey USA 4 Roy Jones Jr USA 4 Arthur Abraham ARM 5 Samuel Peter USA 5 Grigory Drozd RUS 5 Yusaf Mack USA 5 Sakio Bika AUS 6 Denis Boytsov GER 6 Troy Ross CAN 6 Antonio Tarver USA 6 Allan Green USA 7 Oleg Maskaev KAZ 7 B.J. Flores USA 7 Nathan Cleverly WLS 7 Jesse Brinkley USA 8 Alexander Dimitrenko GER 8 Yoan Pablo Hernandez GER 8 Jeff Lacy USA 8 Karoly Balzsay HUN 9 Ruslan Chagaev UZB 9 Denis Lebedev RUS 9 Karo Murat GER 9 Dennis Inkin GER 10 James Toney USA 10 Enad Licina GER 10 Aleksy Kuziemski POL 10 Edison Miranda COL 11 NOT RATED 11 Vadim Tokarev RUS 11 NOT RATED 11 Andre Dirrell USA 12 Ray Austin USA 12 Krzysztof Wlodarczyk POL 12 Chris Henry USA 12 Vitaly Tsypko UKR 13 Fres Oquendo PRI 13 Enzo Maccarinelli WLS 13 Shauna George USA 13 Curtis Stevens USA 14 Johnathon Banks USA 14 Francisco Palacios PRI 14 Vyacheslav Uzelkov UKR 14 Shannan Taylor AUS 15 David Tua USA 15 Alexander Frenkel GER 15 Joey Spina USA 15 Jean Paul Mendy FRA 16 Michael Grant USA 16 Pawel Kolodziej POL 16 Silvio Branco ITA 16 Fulgencio Zuniga COL Page 1/5 MIDDLEWEIGHT (160 LBS) JR. -

P15 Layout 1

MONDAY, SEPTEMBER 11, 2017 SPORTS Pochettino salutes Kane after 100-goal milestone LIVERPOOL: Mauricio Pochettino paid tribute to scored his 100th goal for Tottenham and he ‘ONE OF THE BEST’ struggling to cope with their enforced move to Tottenham forward Harry Kane after he reached 100 deserves a lot of prizes and congratulations for that. Everton manager Ronald Koeman was impressed Wembley for home games this season. goals for his club in an impressive 3-0 victory It’s an unbelievable mark for him.” with the manner of Tottenham’s performance, and “It was a very solid performance,” said against Everton. Kane scored twice at Goodison Kane himself admitted that he did not intend to Kane’s display in particular. Pochettino. “I’m very pleased and happy because it’s Park on Saturday, bringing to an end an unproduc- shoot for that all-important opening goal but, at the “When I speak about Tottenham I mentioned important. We have a very busy period ahead and tive start to the domestic season in which Kane con- start of an important period which sees Spurs start that they have, maybe with Manchester City, the this was a very important victory for us. “I’m very tinued his remarkable record of never having scored their Champions League campaign against Borussia best football side in the Premier League,” said pleased but now we move on, try to recover as soon a Premier League goal in August. Dortmund on Wednesday, he was pleased with the Koeman. as possible and try to be fit for Wednesday and our The England international got back on the score- momentum gained from the win. -

Countdown to Canelo Alvarez Vs. Gennady Golovkin"

**VIDEO ALERT** WATCH NOW! "COUNTDOWN TO CANELO ALVAREZ VS. GENNADY GOLOVKIN" CANELO VS. GOLOVKIN TAKES PLACE SEPT. 16 AT T-MOBILE ARENA IN LAS VEGAS AND PRESENTED LIVE ON HBO PAY-PER-VIEW (ABOVE: Oscar De La Hoya, Chairman and CEO of Golden Boy Promotions, smiles on set behind the scenes while filming "Countdown: Canelo vs. Golovkin.") Click HERE for Behind the Scenes Photos from "Countdown" Click HERE to watch English Version of "Countdown" Click HERE to watch Spanish Version of "Countdown" LOS ANGELES (Aug. 31, 2017) Golden Boy Promotions and Leigh Simons Productions are proud to present "Countdown to Canelo vs. Golovkin," a 30-minute special that features some of the greatest champions of the 160-pound division as they discuss the importance of the showdown between lineal and Ring Magazine champion Canelo Alvarez (49-1-1, 34 KOs) and WBC/WBA/IBF/IBO Gennady "GGG" Golovkin (37-0, 33 KOs)for the middleweight championship of the world.The event will take place Saturday, Sept. 16 at T-Mobile Arena and will be produced and distributed live by HBO Pay-Per- View® beginning at a special time of 8:00 p.m. ET/5:00 p.m. PT. The 30-minute special is now airing on various digital platforms, including HBO Boxing's YouTube channel and Golden Boy Promotion's YouTube channel. ENGLISH VERSION: Watch "Countdown to Canelo vs. Golovkin" <iframe width="560" height="315" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/8jiE1lnXYSA" frameborder="0" allowfullscreen></iframe> SPANISH VERSION: Observa "Countdown to Canelo vs. Golovkin" <iframe width="560" height="315" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/_Hs6nLkM0-0" frameborder="0" allowfullscreen></iframe> Below are highlights from "Countdown: Canelo vs. -

Srisaket Sor Rungvisai Faces Off with Iran Diaz at One: Kingdom of Heroes Open Workout

SRISAKET SOR RUNGVISAI FACES OFF WITH IRAN DIAZ AT ONE: KINGDOM OF HEROES OPEN WORKOUT 28 August 2018 – Bangkok, Thailand: The largest global sports media property in Asian history, ONE Championship™ (ONE), recently held the official ONE: KINGDOM OF HEROES Open Workout at Nakornloung Promotion Gym in Bangkok, Thailand. Set for the Impact Arena on 6 October, ONE: KINGDOM OF HEROES will feature The Ring and WBC Super Flyweight World Champion Srisaket Sor Rungvisai of Thailand, as he defends his title against challenger Iran “MagnifiKO” Diaz of Mexico. For videos, please visit this link: https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1ISTO4hM1-IUvSPvrrmmOxZ hItx_mp11F?usp=sharing For photos, please visit this link: https://drive.google.com/open?id=1XRPGUa3-ZaKamgQFCMAP2MFgFZaJ p82z In attendance at the Open Workout were Srisaket Sor Rungvisai, Iran Diaz, as well as ONE Championship athletes Rika “Tinydoll” Ishige, Sagetdao “Deadly Star” Petpayathai and Petchmorrakot Wor. Sangprapai. Srisaket Sor Rungvisai is one of the most celebrated pugilists in Thailand’s history, winning the prestigious WBC Super Flyweight World Title on two occasions. Holding a professional record of 46-4-1 with 41 knockouts, Sor Rungvisai is ranked No. 5 on the pound-for-pound best boxers list of Boxrec.com and No. 7 on The Ring Magazine’s rankings. After regaining the WBC Super Flyweight World Title in March 2017 and then successfully defending it two times, Sor Rungvisai will now defend his WBC World Title in ONE Championship’s historical event in Thailand, ONE: KINGDOM OF HEROES. Srisaket Sor Rungvisai, WBC Super Flyweight World Champion, stated: “Thank you all for coming out here today. -

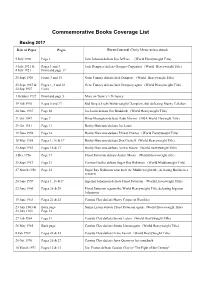

Boxing Edition

Commemorative Books Coverage List Boxing 2017 Date of Paper Pages Event Covered (Daily Mirror unless stated) 5 July 1910 Page 3 Jack Johnson defeats Jim Jeffries (World Heavyweight Title) 3 July 1921 & Pages 1 and 3 Jack Dempsey defeats Georges Carpentier (World Heavyweight Title) 4 July 1921 Front and page 17 25 Sept 1926 Front, 3 and 15 Gene Tunney defeats Jack Dempsey (World Heavyweight Title) 23 Sept 1927 & Pages 1, 3 and 18 Gene Tunney defeats Jack Dempsey again (World Heavyweight Title) 24 Sep 1927 Front 1 October 1927 Front and page 5 More on Tunney v Dempsey 19 Feb 1930 Pages 5 and 22 Kid Berg is Light Welterweight Champion after defeating Mushy Callahan 24 June 1937 Page 30 Joe Louis defeats Jim Braddock (World Heavyweight Title) 21 Oct 1947 Page 7 Rinty Monaghan defeats Dado Marino (NBA World Flyweight Title) 29 Oct 1951 Page 11 Rocky Marciano defeats Joe Louis 19 June 1954 Page 14 Rocky Marciano defeats Ezzard Charles (World Heavyweight Title) 18 May 1955 Pages 1, 16 & 17 Rocky Marciano defeats Don Cockell (World Heavyweight Title) 23 Sept 1955 Pages 16 & 17 Rocky Marciano defeats Archie Moore (World Heavyweight Title) 3 Dec 1956 Page 17 Floyd Patterson defeats Archie Moore (World Heavyweight title) 25 Sept 1957 Page 23 Carmen Basilio defeats Sugar Ray Robinson (World Middleweight Title) 27 March 1958 Page 23 Sugar Ray Robinson wins back the Middleweight title, defeating Basilio in a rematch 28 June 1959 Pages 1, 16 &17 Ingemar Johansson defeats Floyd Patterson (World Heavyweight Title) 22 June 1960 Pages 28 & 29 Floyd Patterson -

Official Ratings As January 2012

2012 Edificio Ocean Business Plaza, Ave. Aquilino de la Guardia con Calle 47, Oficina 1405, Piso 14 Cdad. de Panamá, Panamá Phone: + (507) 340-6425 Web Site: www.wbanews.com WORLD BOXING ASSOCIATION GILBERTO MENDOZA PRESIDENT OFFICIAL RATINGS AS OF NOVEMBER 2012 Based on results held from 04th November to December 04th, 2012 CHAIRMAN MEMBERS MIGUEL PRADO SANCHEZ E-mail: [email protected] GEORGE MARTINEZ CANADA VICE CHAIRMAN JOSE EMILIO GRAGLIA ARGENTINA GUSTAVO PADILLA E-mail: [email protected] ALAN KIM KOREA Over HEAVYWEIGHT 200 Lbs / CRUISERWEIGHT 200 Lbs / LIGHT HEAVYWEIGHT 175 Lbs / 90.71 Kgs 90.71 Kgs 79.38 Kgs SUPER CHAMPION: WORLD CHAMPION: WLADIMIR KLITSCHKO UKR DENIS LEBEDEV RUS WORLD CHAMPION: Won Title: 09-27-08 WORLD CHAMPION: ALEXANDER POVETKIN RUS Last Mandatory: 10-02-10 BEIBUT SHUMENOV KAZ Won Title: 08-27-11 Last Defense: 11-05-11 Won Title: 01-29-10 Last Mandatory: 09-29-12 CHAMPION IN RECESS: Last Mandatory: 07-23-10 Last Defense: 09-29-12 GUILLERMO JONES PAN Last Defense: 06-02-12 WBC: VITALY KLITSCHKO WBC: KRZYSTOF WLODARCZYK WBC: CHAD DAWSON IBF – WBO: WLADIMIR KLITSCHKO IBF: YOAN HERNANDEZ WBO: MARCO HUCK IBF: TAVORIS CLOUD WBO: NATHAN CLEVERLY 1. DAVID HAYE (WBA I/C) GBR 1. OFFICIAL CHALLENGER VACANT 1. GAYRAT AHMEDOV (WBA INT) UZB 2. LUIS ORTIZ (INTER) CUB 2. PAWEL KOLODZIEJ POL 2. BERNARD HOPKINS USA 3. RUSLAN CHAGAEV UZB 3. BJ FLORES (NABA) USA 3. EDUARD GUTKNECHT (EBU) KAZ 4. KUBRAT PULEV BUL 4. LAUDELINO BARROS BRA 4. VYACHESLAV UZELKOV UKR 5. DENIS BOYTSOV RUS 5. IAGO KILADZE (WBA I/C) GEO 5. -

Brook + Wilder + Taylor + Kovalev

BROOK + WILDER + TAYLOR + KOVALEV MARCH 1 2018 Every week THE AWARD-WINNING WORLD’S BEST FIGHT MAGAZINE EST. 1909 T WWW.BOXINGNEWSONLINE.NE NEVER FORGET Scott Westgarth 1986-2018 9 NO. 74 VOL. £3.49 Est. 1909 WHERE DOES YOUR FAVOURITE BRITISH BOXER RANK? Order today at www.boxingnewsonline.net/shop quoting GBB17 Also available at local newsagents or via the Boxing News app Retail price £7.99 ContMarchen 1, 2018 ts R.I.P SCOTT WESTGARTH 38 Tragedy strikes in a British ring, as 31-year-old loses his life Photos: ACTION IMAGES/ADAM HOLT & ED MULHOLLAND/HBO DON’T MISS HIGHLIGHTS >> 10 BROOK IS BACK >> 4 EDITOR’S LETTER An exclusive interview with Kell, as well This must serve as a wake-up call as a preview of the Rabchenko clash >> 5 GUEST COLUMN >> 16 POWER SURGE A comment from the BBBofC Who will win the world heavyweight title clash between Wilder and Ortiz? >> 26 THE OBSESSION Catching up with Jazza Dickens – >> 20 KEEP ON KRUSHIN’ a man who is addicted to boxing Looking ahead to Kovalev’s collision with his fellow Russian, Mikhalkin >> 30 FIGHT OF THE YEAR! A ringside report from the sensational >> 22 SCOTTISH SUPPORT Srisaket-Estrada super-fly spectacle Taylor prepares to face a late 30 substitute in front of his home fans >> 32 FITTING FINALE Smith sets up a mouth-watering WBSS final with Groves – injury-permitting DOWNLOAD OUR APP TODAY >> 42 AMATEURS For more details visit The Lionhearts head to Liverpool WWW.BOXINGNEWSONLINE.NET/SUBSCRIPTIONS >> 46 60-SECOND INTERVIEW ‘AS I REALLY DEVELOPED IN THE SPORT, I ALWAYS LOOKED UP TO BERNARD -

“Ggg” Takes Manhattan!!!

“GGG” TAKES MANHATTAN!!! New York City (April 28, 2015) This past weekend Boxing Superstar GENNADY “GGG” GOLOVKIN visited New York City in a whirlwind promotional trip just three week ahead of his World Middleweight Championship battle against WILLIE MONROE JR. on Saturday, May 16 at the Forum in Los Angles, California and televised Live on HBO World Championship Boxing® beginning at 10:00 p.m. ET/PT. Golovkin departed from his Big Bear, California training camp at 2:00 a.m. PT on Friday morning for an early morning flight to New York City. On Friday night, he was presented with an award for the Highest Knockout Percentage in the History of the Middleweight Division at the 2015 Boxing Writers Association of America Awards Dinner. On Saturday afternoon, Golovkin held court for a massive turnout of international press at a media lunch held in Mid‐town. Saturday night, Golovkin headed to Madison Square Garden for the World Heavyweight Championship between Wladimir Klitschko and Bryant Jennings where he was interviewed on the HBO telecast. Before departing on Sunday, Golovkin voted in the election for President of Kazakhstan at the Kazakhstan Consulate in New York City. Below are quotes from Golovkin’s media lunch. GENNADY “GGG” GOLOVKIN “Willie Monroe is a slick southpaw and this presents a challenging style for me to fight. This is what I wanted. “ “My focus is on Willie Monroe, I’m not concerned right now with any other fights. “ “I’m very happy living in Los Angeles, my family is with me now. “ “My power comes from hard work everyday in the gym.” TOM LOEFFLER, K2 Promotions “Willie Monroe has a very unconventional style which is a challenge for Gennady and made the most sense.