Straight Men Come Out: Queer Eye and the Path to a More Mindful Masculinity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

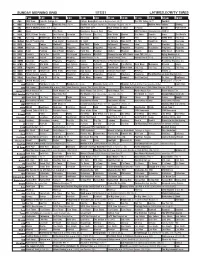

Sunday Morning Grid 1/17/21 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 1/17/21 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Face the Nation (N) News College Basketball Iowa at Northwestern. (N) Å The NFL Today (N) Å Football 4 NBC Today in LA Weekend Meet the Press (N) Å Hockey Washington Capitals at Pittsburgh Penguins. (N) Å Mecum Auto Auctions Skating 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch Emeril Pain Relief! 7 ABC News This Week Eyewitness News at 9am News AKC National Championship 2020 Å 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday Joel Osteen Jeremiah Joel Osteen Paid Prog. Mike Webb Harvest Sex Abuse Danette Icons The World’s 1 1 FOX Paid Prog. MAXX Oven Fox News Sunday The Issue News Sex Abuse AAA PiYo Paid Prog. MAXX Oven Paid Prog. 1 3 MyNet Bel Air Presbyterian Fred Jordan Freethought In Touch On Camera Rare 1899 Dr. Ho’s Caught on News The Issue 1 8 KSCI Smile Copper Workout! AAA New YOU! Smile Bathroom? Cleanse Ideal AAA Prostate Paid Prog. 2 2 KWHY Más Pelo Programa Resultados Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Resultados Programa Programa 2 4 KVCR Paint Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexican Queens Lidia Milk Street Field Trip 2 8 KCET Darwin’s Cat in the SciGirls Odd Squad Cyberchase Biz Kid$ Memory Rescue With Daniel Amen, MD (TVG) Å Aging Backwards 3 3 0 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Amazing Hawaii Five-0 (TV14) Hawaii Five-0 (TV14) Hawaii Five-0 (TV14) Hawaii Five-0 (TV14) 3 4 KMEX Conexión Programa Programa Programa Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División (N) República Deportiva (N) 4 0 KTBN R. -

The New Yorker April 05, 2021 Issue

PRICE $8.99 APRIL 5, 2021 APRIL 5, 2021 4 GOINGS ON ABOUT TOWN 11 THE TALK OF THE TOWN Jonathan Blitzer on Biden and the border; from war to the writers’ room; so far no sofas; still Trump country; cooking up hits. FEED HOPE. ANNALS OF ASTRONOMY Daniel Alarcón 16 The Collapse at Arecibo FEED LOVE. Puerto Rico loses its iconic telescope. SHOUTS & MURMURS Michael Ian Black 21 My Application Essay to Brown (Rejected) DEPT. OF SCIENCE Kathryn Schulz 22 Where the Wild Things Go The navigational feats of animals. PROFILES Rachel Aviv 28 Past Imperfect A psychologist’s theory of memory. COMIC STRIP Emily Flake 37 “Visions of the Post-Pandemic Future” OUR LOCAL CORRESPONDENTS Ian Frazier 40 Guns Down How to keep weapons out of the hands of kids. FICTION Sterling HolyWhiteMountain 48 “Featherweight” THE CRITICS BOOKS Jerome Groopman 55 Assessing the threat of a new pandemic. 58 Briefly Noted Madeleine Schwartz 60 The peripatetic life of Sybille Bedford. PODCAST DEPT. Hua Hsu 63 The athletes taking over the studio. THE ART WORLD Peter Schjeldahl 66 Niki de Saint Phalle’s feminist force. ON TELEVISION Doreen St. Félix 68 “Waffles + Mochi,” “City of Ghosts.” POEMS Craig Morgan Teicher 35 “Peers” Kaveh Akbar 52 “My Empire” COVER R. Kikuo Johnson “Delayed” DRAWINGS Johnny DiNapoli, Tom Chitty, P. C. Vey, Mick Stevens, Zoe Si, Tom Toro, Adam Douglas Thompson, Suerynn Lee, Roz Chast, Bruce Eric Kaplan, Victoria Roberts, Will McPhail SPOTS André da Loba CONTRIBUTORS Caring for the earth. ©2020 KENDAL Rachel Aviv (“Past Imperfect,” p. 28) is a Ian Frazier (“Guns Down,” p. -

Television Academy Awards

2021 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Host For A Reality Or Competition Program Dan Abrams, Host Court Cam Ted Allen, Host Chopped Tim Allen, Host Richard Karn, Host Assembly Required Anthony Anderson, Host To Tell The Truth Alec Baldwin, Host Match Game Elizabeth Banks, Host Press Your Luck Tyra Banks, Host Dancing With The Stars Bobby Berk, Host Karamo Brown, Host Tan France, Host Antoni Porowski, Host Jonathan Van Ness, Host Queer Eye Wayne Brady, Host Game Of Talents Christopher "Ludacris" Bridges, Host Luda Can't Cook Michelle Buteau, Host The Circle Nicole Byer, Host Nailed It! Nick Cannon, Host The Masked Singer John Cena, Host Nicole Byer, Host Camille Kostek, Host Wipeout RuPaul Charles, Host RuPaul's Drag Race Julie Chen-Moonves, Host Big Brother: All Stars Terry Crews, Host America's Got Talent Elizabeth Cronin, Host Maurice Harris, Host Simon Lycett, Host Full Bloom Mark Cuban, Host Barbara Corcoran, Host Lori Greiner, Host Robert Herjavec, Host Daymond John, Host Kevin O'Leary, Host Shark Tank Carson Daly, Host The Voice Ellen DeGeneres, Host Ellen's Game Of Games Scott Evans, Host World Of Dance Craig Ferguson, Host The Hustler Bobby Flay, Host Beat Bobby Flay Scott Foley, Host Ellen's Next Great Designer Bethenny Frankel, Host The Big Shot With Bethenny Selena Gomez, Host Selena + Chef Bear Grylls, Host Running Wild With Bear Grylls Bear Grylls, Host World’s Toughest Race: Eco-Challenge Fiji Tiffany Haddish, Host Kids Say The Darndest Things Chris Hardwick, Host The Wall Allison Holker Boss, Host Design Star: Next -

|||GET||| the Edge the War Against Cheating and Corruption in The

THE EDGE THE WAR AGAINST CHEATING AND CORRUPTION IN THE CUTTHROAT WORLD OF ELITE SPORTS 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE Roger Pielke | 9781938901577 | | | | | The Edge, by Roger Pielke Jr Whatever life brings, Cory's gassed up and ready to go! And better or worse depends on what we think is a problem in the first place, or whether we think that there even is a problem requiring action. The second subtrend underlying continued economic growth is a major expan- sion of foreign direct investment FDI by multinational corporations. The dominant orientation, however, is the discipline of management and, within it, the study of strategic management, or actions that adapt the company to its changing environment. No accurate or com- plete maps existed; even its exact boundaries were vague. As in the old days, its power is challenged and limited by economic, political, and social forces. With more terri- tory they acquired new natural resources, agriculture, and labor. Then Astor crushed the competition. The first is theory describing how corporations interact with stakeholders. Its main business is discovering, producing, and selling oil and natural gas, and it has a long record of profiting more at this business than its rivals. High Score Aug. Furs taken in the West would come to Astoria and then be shipped to China, which was a major fur market, or to New York. About this product Product Information Roger Pielke reveals how sports stars break the rules in their search for a competitive edge. This role grew in the twenti- eth century as many nations expanded their electorates. -

Outstanding Lighting Design/Lighting Direction for a Variety Special

2021 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Lighting Design/Lighting Direction For A Variety Series The Amber Ruffin Show Episode 117 In this episode of The Amber Ruffin Show, Amber’s first audience member is attacked after stealing her sidekick’s joke, Amber previews a movie chronicling Harriet Tubman’s true dream, sings a song about her fear of the coronavirus, and coaches the parents who opposed transgender representation in a school book program. America's Got Talent The Finals The top 10 acts perform one last time from Universal Studios for their chance to win $1 million and be named the most talented act in America. American Idol Episode 419 Season 4 of American Idol concludes with the top three finalists taking the stage one last time in hopes of securing America’s vote to becoming this season’s winner. In addition to the top 3, former contestants returned to join renowned music artists for unforgettable performances throughout the show. Antiques Roadshow American Stories Antiques Roadshow transports audiences across America to discover captivating stories about items ranging from the everyday to the extraordinary. For the first time, Antiques Roadshow visits with notable people from comedy, film, TV, literature, music, and sports to learn about their personal treasures while exploring our collective history. A Black Lady Sketch Show If I’m Paying These Chili’s Prices, You Cannot Taste My Steak! A common Black figure-of-speech comes alive; commentators analyze a high-stakes search for a cafeteria seat; a fast-paced nail appointment gets pricey; a woman uses a cult-like seminar to scare off her friend; a psycho tampers with his hostage’s purse; a woman reaches hair nirvana; the women stage a presidential debate. -

June 17, 2020 the QUEER EYE: OG MEMBERS WILL GO HEAD

June 17, 2020 THE QUEER EYE: OG MEMBERS WILL GO HEAD-TO-HEAD WITH MEMBERS OF THE QUEER EYE: THE NEW CLASS IN A RARE JOINT APPEARANCE ON ABC’S ‘CELEBRITY FAMILY FEUD’ Emmy® Award Winner Steve Harvey, Popular Stand-Up Comedian, Actor and Author, Returns to Host Photo credit: ABC/Byron Cohen* For additional “Celebrity Family Feud” photos, click here. “Queer Eye: OG vs. Queer Eye: The New Class” – “Celebrity Family Feud,” where celebrity families compete to win cash for their charities, kicks off season six with the beloved OG Queer Eye team, led by Carson Kressley, playing against the new class members from Netflix’s hit show “Queer Eye,” led by Bobby Berk, in a hilarious one-hour episode. The all-star episode airs SUNDAY, JULY 5 (8:00-9:00 p.m. EDT), on ABC. (TV-14, DL) Episodes can also be viewed on demand and on Hulu. (Rebroadcast. OAD: 5/31/20) Hosted by the highly popular stand-up comedian, actor, author and Emmy® Award winner Steve Harvey, “Celebrity Family Feud” returns for its sixth season, kicking off ABC’s popular “Summer Fun & Games.” Once again, celebrities, along with their families and friends, go head-to-head in a contest to name the most popular responses to survey-type questions posed to 100 people to win money for a charity of their choice. The celebrity teams who will try to guess what the “survey said” are the following: Queer Eye: OG; playing for The Trevor Project o Carson Kressley – VH-1’s “RuPaul’s Drag Race” o Ted Allen – host, Food Network’s “Chopped” and “Chopped Junior” o Kyan Douglas – “Queer Eye” grooming expert o Thom Filicia – design expert o Jai Rodriguez – Disney+’s “ Diary of a Future President” VERSUS Queer Eye: The New Class; playing for GLSEN o Bobby Berk – host, “Queer Eye” o Jonathan Van Ness – host, “Queer Eye” o Antoni Porowski – host, “Queer Eye” o Tan France – host, “Queer Eye” o Wesley Hamilton – season four hero “Celebrity Family Feud” is produced by Fremantle and was taped in February 2020 in front of a live audience in Los Angeles, California. -

A STAND Talking with Queer Activist PAGE 6

Alice Cozad and Linda Young. Photos courtesy of the couple VOL 35, NO. 23 AUG. 5, 2020 PAGE 10 www.WindyCityMediaGroup.com KEN ILIO Gay-marriage pioneer dies at 63. Photo of Ilio, left, and husband Ron Dorfman by Hal Baim ETERNAL 5 MODEL CITIZEN Jay Manuel releases new book. FLAME Photo by Troy Word Lesbian couple together for 50 years 13 YVONNE ZIPTER TAKING Chicagoan on upcoming poetry collection. Book cover A STAND Talking with queer activist PAGE 6 Asha Ransby-Sporn Asha Ransby-Sporn. 16 Photo by Texas Isaiah @windycitytimes /windycitymediagroup @windycitytimes www.windycitymediagroup.com 2 Aug. 5, 2020 WINDY CITY TIMES PAGE 6 Chicago Pride Parade 2019. Photo by Kat Fitzgerald (www.MysticImagesPhotography.com) "Kickoff," The Chicago Gay Pride Parade 1976. Diane Alexander White Photography TWO SIDES OF PAGE 20 YESTERDAY APRIL 29, 2020 VOL 35, NO. 20 Looking back at Pride memories of the past (above) WINDYJUNE 24, 2020 and this month’s Drag March for Change (below) PRIDEChicagoBuffalo Pridedrives Grove postponed; on Pride VOL 35, NO. 16 CITY www.WindyCityMediaGroup.com AND TODAY EDDIE TIMES HUNSPERGER PAGE 17 Activist and partner of Rick Garcia dies. Photo of Hunsperger (right) and Garcia courtesy of Garcia 4 Buffalo Grove Pride 2019. SEEING Tim Carroll Photography THE LIGHT Lighthouse Foundation prepares programming. Photo of Rev. Jamie Frazier by Marcel Brunious 8 PAGE 4 www.windycitymediagroup.com From the Drag March for Change. Photo by Vernon Hester @windycitytimes /windycitymediagroup @windycitytimes www.windycitymediagroup.com @windycitytimes FUN AND GUNN Tim Gunn on his new show, /windycitymediagroup 'Making the Cut'. Photo by Scott McDermott 13 @windycitytimes SUPPORT Photo by Tim Peacock VOL 35, NO. -

Love for Reading Blooms in Saugus She Wanted to Open.” Forward Without the Ward According to the Essex Councilor’S Support

SATURDAY, APRIL 6, 2019 Lozzi: Chestnut St. not right spot for pot $1.4M By Gayla Cawley city councilor that the city of Lynn voted Support and opposition from neighbors ITEM STAFF for recreational marijuana. However, it was about even, he said, with concerns string needs to be located in the right place and centering around parking, traf c, its LYNN — Ward 1 City Councilor Wayne I don’t think this is the right t for that proximity to St. Pius V School and how it Lozzi is opposed to a proposed pot shop on Chestnut Street. His opposition may kill type of business.” wouldn’t t with the image of the residen- attached the proposal. Lozzi said there are other places in the tial neighborhood. Heather Hannon, owner and CEO of ward that would be a better t for a pot “I went into it with an open mind, but Essex Apothecary, is proposing a bou- shop, such as Boston Street, Goodwin Cir- enough residents made it clear to me that to Lynn tique recreational marijuana shop at 548 cle or Western Avenue. it’s not a good location,” Lozzi said. “Per- Chestnut St. A neighborhood meeting was held on sonally, I think if adults want to smoke “It’s just not a good t for that neigh- Wednesday for the proposed shop, which pot, it’s OK, but my concern is with kids. I borhood,” said Lozzi, whose ward includes Lozzi said was well-attended by about 80 school aid the proposed shop location. “I realize as a residents. -

Your Montreal Cheat Sheet + King Princess * POP Montreal * Luna & More

SEPTEMBER 2019 • Vol. 8 No. 1 8 No. Vol. SEPTEMBER 2019 • • CULTMTL.COM FREE Your Montreal cheat sheet + King Princess * POP Montreal * Luna & more letter table of Cult Mtl from the is... Part 1 07.06–08.09.2019 contents Part 2 27.09.2019–19.01.2020 editor Rising NYC pop-rock star King Princess on sexuality and Lorraine Carpenter gender, art and feelings and editor-in-chief Part 3 07.02–17.05.2020 getting into the music business [email protected] the right way. Hey students, Photo by Vince aung alex Rose Sortis du cadre : film editor [email protected] Welcome back, and welcome to Cult MTL’s Nora Rosenthal arts editor Out of the Box: eighth annual Student Survival Guide. [email protected] letter from the editor 4 Clayton Sandhu Going back to school doesn’t have to hurt so contributing editor (food) Gordon MATTA-CLARK hard. This city is buzzing with enough activity to-do list 7 and entertainment to get you through the year, Chris Tucker city 8 and balancing your studies with an exciting art director Revu par and rewarding social life is easy, and even :persona mtl 8 affordable. food & drink 10 advertising [email protected] Selected by Yann Chateigné Luna 10 Let us steer you. Because that's what we do. Contributors: music 12 dave Jaffer Along with offering a pile of practical King Princess 12 darcy Macdonald Hila Peleg information to help you navigate the city and POP Montreal 14 Special thanks: gregory Vodden make the best use of its many services, this studENT surviVaL gUidE 16 Kitty Scott guide features pointers on Montreal food, eating 16 nightlife, shopping and art, along with loads of other leisure activities, from cycling to spas. -

Tan France to Host 'The Audie Awards'

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Danielle Katz, The Media Grind (818) 823-6603 TAN FRANCE TO HOST ‘THE AUDIE AWARDS’ AND CELEBRATE ACHIEVEMENTS IN AUDIOBOOKS New York, NY – February 4, 2019 – The Audio Publishers Association (APA), the premiere trade organization of audiobooks and spoken word entertainment, announces today that Queer Eye fashion expert and upcoming author and audiobook narrator, Tan France, will host the 2019 Audie Awards. This year’s award ceremony and reception is getting a makeover with a high-profile host and judging panel. The prestigious event is best known as a gathering of authors, narrators, and publishers with 24 competitive categories being awarded throughout the th evening. The ceremony will take place on March 4 , 2019, at Guastavino’s in New York City. “We’re so honored to have audiobook fan and soon-to-be author, Tan France, help raise the bar and bring more excitement to the fastest-growing format in publishing,” said Michele Cobb, Executive Director of the APA. “Tan will be a wonderful addition to the 2019 Audie Awards, commanding and enchanting the room full of publishing personalities. We’re thrilled to have him introduce this year’s esteemed judging panel and bring audiobooks and the 2019 Audiobook of the Year to a national stage.” Tan France is a well-known fashion designer, stylist, and star of the Emmy award-winning Netflix reboot, Queer Eye. This spring, Tan France will be releasing his first memoir and self-narrated audiobook, Naturally Tan. The 2019 esteemed judging panel includes: Ron Charles, Book Critic for The Washington Post Lisa Lucas, Executive Director of the National Book Foundation. -

Face It: This Is a Sweet Fundraising Ideadeals of the by Bella Digrazia Ralysis of the Stomach, While Having Fun

DEALS OF THE $DAY$ PG. 3 SATURDAY, JUNE 29, 2019 DEALS OF THE $DAY$ PG. 3 DEALS OF THE $DAY$ PG. 3 Face it: This is a sweet fundraising ideaDEALS OF THE By Bella diGrazia ralysis of the stomach, while having fun. eld was something I looked forward to every Andrew Belliveau of ITEM STAFF “I was diagnosed with it when I was 10 years week.” Lynn, $whoDA hasY $lived old,” said Belliveau. Going through it at such a The reason behind the pie? Belliveau said with gastroparesisPG. 3 for LYNN — Andrew Belliveau, 22, is ready to young age, I never fully understood what was with the illness, he is unable to digest certain 10 years, pies himself smash gastroparesis out of the park for the in the face to raise second year in a row. going on so I was just going through the mo- things so when the holidays come around he awareness for his The Lynn native is hosting his 2nd Annual tions and forcing myself to go to school for an can’t indulge in his favorite desserts, such as cause and the GP Pie- “GP Pie-A-Thon” on Sunday, from 10 a.m. to 2 hour or two at most, so I wouldn’t get behind. pies. A-Thon he is hosting p.m., at Gowdy Memorial Park in Lynn. Inspired Being away from my friends was very dif - “After you smash it in your face the rst in- DEALS by the “Ice-Bucket Challenge,” which raised mil- cult and I remember baseball being my oasis stinct is to lick it off, but for us gastro-patients, on Sunday at Gowdy lions of dollars to combat Lou Gehrig’s disease, because the mental aspect of the game dis- you can’t,” he said. -

ENGAGE Inelegant Engagement Workshop Report

ENGAGE 2019 INELEGANCE AND WHY WE MIGHT DESIRE IT WORKSHOP REPORT Bentley Crudgington ABSTRACT In founding Gay Men’s Health Crisis (GMHC) and the AIDS Coalition To Unleash Power (ACT-UP), Larry Kramer created two of the earliest centrally organised examples of health research engagement and public and patient involvement. These activists were not rejecting the research itself but denouncing its “elegant” nature. What would inelegant engagement look like and why might we desire it? What would it look like if we acted up and queered engagement, lavishing our time, skills, creativity and resources on the public and not researchers? This participatory workshop will explore these possibilities to produce an inelegant manifesto of change. FORMAT As an introduction to the concept of inelegance, and why we might desire it, we considered some of the inventions used by ACT UP and compared them with two current areas of social theory. We borrowed from queer theory and visual culture analysis to consider how we, as engagement professionals, frame our invitations, construct our publics and operate within institutional structures. We used these experiences to identify what systems need to be in place and which barriers need managing to allow us to become inelegant. We reviewed these ideas together and clustered them into emerging themes. We then named each cluster with an action to create an inelegant manifesto. This report summarises what we learnt together. In January 1982, Larry Kramer, a New York based writer, held a gathering of around eighty gay men at his apartment to discuss the emerging reports of a “gay cancer”.