Elevator to Nostalgia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exploring the Portrayal of Stuttering in It (2017)

POSTS AND G-G-GHOSTS: EXPLORING THE PORTRAYAL OF STUTTERING IN IT (2017) A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Communication, Culture, and Technology By Mary-Cecile Gayoso, B. A Washington, D.C. April 13, 2018 Copyright 2018 by Mary-Cecile Gayoso All Rights Reserved ii Dedication The research and writing of this thesis is dedicated to my parents and the name they gave me MY PARENTS, for always listening, for loving me and all my imperfections, and for encouraging me to speak my mind always MY NAME, for being simultaneously the bane and joy of my existence, and for connecting me to my Mamaw and to the Grandfather I never knew Thank you, I love you, Mary-Cecile iii Acknowledgements “One of the hardest things in life is having words in your heart that you can't utter.” - James Earl Jones This thesis would not have been possible without those that are part of my everyday life and those that I have not spoken to or seen in years. To my family: Thank you for your constant support and encouragement, for letting me ramble about my thesis during many of our phone calls. To my mother, thank you for sending me links about stuttering whenever you happened upon a news article or story. To my father, thank you for introducing me to M*A*S*H as a kid and to one of the most positive representations of stuttering in media I’ve seen. -

Doctor Sleep : Film Tie-In PDF Book

DOCTOR SLEEP : FILM TIE-IN PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Stephen King | 512 pages | 19 Sep 2019 | HODDER & STOUGHTON | 9781529375077 | English | United Kingdom Doctor Sleep : Film Tie-In PDF Book Related Posts. Store Locations. This item will be sent through the Global Shipping Programme and includes international tracking. Another major connection is alcoholism. Description Details GoodReads Reviews Stephen King returns to the characters and territory of one of his most popular novels ever, The Shining, in this instantly riveting novel about the now middle-aged Dan Torrance the boy protagonist of The Shining and the very special year-old girl he must save from a tribe of murderous paranormals. Learn More - opens in a new window or tab. Tine minte cum ai ales sa iti folosesti datele cu caracter personal pe acest site. Tom Reimann Articles Published. People who viewed this item also viewed. Title of the book contains:. Memoreaza numarul comenzii pe care tocmai ati plasat-o pentru a va oferi optiuni suplimentare in pagina urmatoare. Contact seller. Replacement 15 days easy replacement. The consignee will be responsible for both customs clearance and payment of customs duties and local taxes where required. Description Postage and payments. Due to our competitive pricing, we may have not sold all products at their original RRP. He lives in Bangor, Maine, with his wife, novelist Tabitha King. Beneficiezi de preturi promotionale. All of our paper waste is recycled and turned into corrugated cardboard. So, both The Shining and Doctor Sleep begin with father and son respectively being given a second chance to stop destroying themselves with liquor. -

Shining” with the Marginalized: Self-Reflection and Empathy in Stanley Kubrick’S the Hinins G Bethany Miller Cedarville University, [email protected]

Cedarville University DigitalCommons@Cedarville Department of English, Literature, and Modern English Seminar Capstone Research Papers Languages 4-22-2015 “Shining” with the Marginalized: Self-Reflection and Empathy in Stanley Kubrick’s The hininS g Bethany Miller Cedarville University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/ english_seminar_capstone Part of the Film Production Commons, Literature in English, North America Commons, Literature in English, North America, Ethnic and Cultural Minority Commons, Other Film and Media Studies Commons, and the Screenwriting Commons Recommended Citation Miller, Bethany, "“Shining” with the Marginalized: Self-Reflection and Empathy in Stanley Kubrick’s The hininS g" (2015). English Seminar Capstone Research Papers. 30. http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/english_seminar_capstone/30 This Capstone Project is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Cedarville, a service of the Centennial Library. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Seminar Capstone Research Papers by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Cedarville. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Miller 1 Bethany Miller Dr. Deardorff Senior Seminar 8 April 2015 “Shining” with the Marginalized: Self-Reflection and Empathy in Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining Stanley Kubrick’s horror masterpiece The Shining has confounded and fascinated viewers for decades. Perhaps its most mystifying element is its final zoom, which gradually falls on a picture of Jack Torrance beaming in front of a crowd with the caption “July 4 th Ball, Overlook Hotel, 1921.” While Bill Blakemore and others examine the film as a critique of violence in American history, no scholar has thoroughly established the connection between July 4 th, 1921, Jack Torrance, and the rest of the film. -

Tracking the Research Trope in Supernatural Horror Film Franchises

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2-2020 Legend Has It: Tracking the Research Trope in Supernatural Horror Film Franchises Deirdre M. Flood The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/3574 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] LEGEND HAS IT: TRACKING THE RESEARCH TROPE IN SUPERNATURAL HORROR FILM FRANCHISES by DEIRDRE FLOOD A master’s thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, The City University of New York 2020 © 2020 DEIRDRE FLOOD All Rights Reserved ii Legend Has It: Tracking the Research Trope in Supernatural Horror Film Franchises by Deirdre Flood This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in satisfaction of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts. Date Leah Anderst Thesis Advisor Date Elizabeth Macaulay-Lewis Executive Officer THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Legend Has It: Tracking the Research Trope in Supernatural Horror Film Franchises by Deirdre Flood Advisor: Leah Anderst This study will analyze how information about monsters is conveyed in three horror franchises: Poltergeist (1982-2015), A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984-2010), and The Ring (2002- 2018). My analysis centers on the changing role of libraries and research, and how this affects the ways that monsters are portrayed differently across the time periods represented in these films. -

Jack Torrance S Haunting in

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Ondřej Parýzek Jack Torrance’s Haunting in Stephen King’s The Shining Bachelor’s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: Mgr. Jan Čapek 2019 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. ……………………………………………… Author’s signature Acknowledgement I would like to thank my supervisor Jan Čapek for his guidance and invaluable advice. Table of Contents Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 5 1. Theoretical Section ............................................................................................................ 7 1.1. The Gothic .................................................................................................................. 7 1.1.1. The Haunted Place and its Place in the New American Gothic ..................... 7 1.1.2. The Ghost ............................................................................................................ 9 1.2. Psychoanalysis .......................................................................................................... 12 1.2.1. The Uncanny, Haunting and Mirroring ......................................................... 12 1.2.2. Narcissistic Injury ............................................................................................ 15 2. Analytical Section ........................................................................................................... -

Melbourne It Announces Agreement with Yahoo! Melbourne IT Selected to Provide Domain Registration Services for Yahoo! Melbourne -- February

Melbourne It Announces Agreement With Yahoo! Melbourne IT Selected to Provide Domain Registration Services for Yahoo! Melbourne -- February. 13, 2001 -- Melbourne IT (ASX: MLB), a leading supplier of domain names and e-commerce infrastructure services to the global market, today announced an agreement with Yahoo! Inc. (Nasdaq:YHOO), a leading global Internet communications, commerce and media company. Through the agreement, Melbourne IT will provide .com, .net and .org domain names to users of Yahoo!® Domains (http://domains.yahoo.com), a service Yahoo! launched in May 2000 that allows people to search for, register and host their own domain names. "Yahoo! is synonymous with the Internet, and we believe the credibility associated with the Yahoo! brand will increase our domain name registrations and strengthen our position in the market," said Adrian Kloeden, Melbourne IT's Chief Executive Officer. "The agreement further supports Melbourne IT's strategy to become a leading worldwide provider of domain registration services and highlights our key strengths in providing domain names and related services." Also through the agreement, Melbourne IT will provide backend domain registrations for users of other Yahoo! properties, including Yahoo! Website Services (http://website.yahoo.com), Yahoo! Servers (http://servers.yahoo.com) and the Personal Address feature for Yahoo! Mail (http://mail.yahoo.com), all of which offer users a comprehensive suite of services to create and maintain a presence on the Web. "We are pleased to be working with Melbourne IT to provide Yahoo! Domains users with reliable and comprehensive domain name registration solutions," said Shannon Ledger, vice president and general manager, production, Yahoo!. -

Newsletter 01/20 (Nr

ISSN 1610-2606 ISSN 1610-2606 newsletterDIGITAL EDITION Nr. 378 -01/20 Januar 2020 Michael J. Fox Christopher Lloyd Cordula Kablitz-Post Regisseurin („Weil Du nur einmal lebst - Die Toten Hosen auf Tour“) LASER HOTLINE - Inh. Dipl.-Ing. (FH) Wolfram Hannemann, MBKS - Talstr. 11 - 70825 K o r n t a l Fon: 0711-832188 - Fax: 0711-8380518 - E-Mail: [email protected] - Web: www.laserhotline.de Newsletter 01/20 (Nr. 378) Januar 2020 editorial Hallo Laserdisc- und DVD-Fans, besorgen wir Ihnen auch weiterhin alle PLACE – das neue Tonformat aus dem liebe Filmfreunde! international verfügbaren DVD-, BD- und Hause Dolby rockt! Einen kleinen Wer- UHD-Titel. Aber das wissen Sie ja be- mutstropfen müssen wir aber vorerst Falls Sie sich angesichts unseres Titel- reits. noch schlucken: es brummt aus unseren bildes jetzt fragen sollten, ob Sie womög- Lautsprechern. Nicht arg laut, aber für lich aufgrund zu hohen Alkoholkonsums Natürlich füttern wir auch nach wie vor feine Ohren wie die unseren trotzdem während des Jahreswechsels plötzlich unseren YouTube-Kanal “Laser Hotline” störend. Das wird noch einiges an de- alles doppelt sehen, so können wir Sie mit interessanten Interviews und tektivischer Arbeit erfordern, um den lä- beruhigen. Denn auf unserem Titelbild Featurettes zu aktuellen Kinofilmen. stigen Störer zum Schweigen zu bekom- sehen Sie tatsächlich zwei Personen. Kinofilme? Nicht nur! Denn erst kürzlich men. Aber wir sind zuversichtlich – allei- Oder besser ausgedrückt: zwei Persön- haben wir dort ein Video eingestellt, in ne an der Zeit fehlt es momentan. Jedoch lichkeiten. Denn die Zwillinge Jana und dem es um eine TV-Produktion geht, die freuen wir uns in diesem Zusammenhang Sophie Münster haben es in ihrer im Juli im SWR Fernsehen ausgestrahlt darüber, dass die Netflix-Produktion Schauspielerkarriere auf immerhin drei wird: DANCE AROUND THE WORLD, ROMA von Alfonso Cuaron endlich den HANNI UND NANNI Filme gebracht. -

March 30, 2010 (XX:11) Stanley Kubrick, the SHINING (1980, 146 Min)

March 30, 2010 (XX:11) Stanley Kubrick, THE SHINING (1980, 146 min) Directed by Jules Dassin Directed by Stanley Kubrick Based on the novel by Stephen King Original Music by Wendy Carlos and Rachel Elkind Cinematography by John Alcott Steadycam operator…Garrett Brown Jack Nicholson...Jack Torrance Shelley Duvall...Wendy Torrance Danny Lloyd...Danny Torrance Scatman Crothers...Dick Hallorann Barry Nelson...Stuart Ullman Joe Turkel...Lloyd the Bartender Lia Beldam…young woman in bath Billie Gibson…old woman in bath Anne Jackson…doctor STANLEY KUBRICK (26 July 1928, New York City, New York, USA—7 March 1999, Harpenden, Hertfordshire, England, UK, natural causes) directed 16, wrote 12, produced 11 and shot 5 films: Eyes Wide Shut (1999), Full Metal Jacket (1987), The Shining Lyndon (1976); Nominated Oscar: Best Writing, Screenplay Based (1980), Barry Lyndon (1975), A Clockwork Orange (1971), 2001: A on Material from Another Medium- Full Metal Jacket (1988). Space Odyssey (1968), Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964), Lolita (1962), Spartacus STEPHEN KING (21 September 1947, Portland, Maine) is a hugely (1960), Paths of Glory (1957), The Killing (1956), Killer's Kiss prolific writer of fiction. Some of his books are Salem's Lot (1974), (1955), The Seafarers (1953), Fear and Desire (1953), Day of the Black House (2001), Carrie (1974), Christine (1983), The Dark Fight (1951), Flying Padre: An RKO-Pathe Screenliner (1951). Half (1989), The Dark Tower (2003), Dark Tower: The Song of Won Oscar: Best Effects, Special Visual Effects- 2001: A Space Susannah (2003), The Dark Tower: The Drawing of the Three Odyssey (1969); Nominated Oscar: Best Writing, Screenplay Based (2003), The Dark Tower: The Gunslinger (2003), The Dark Tower: on Material from Another Medium- Dr. -

Chorus Songs –Sp

Chorus songs –Spring 2014 I Love the Summer Warm, warm weather makes me smile, makes me happy. Love the summer. Yes, I Warm, warm weather makes me smile, makes me happy. Love the summer. Well, I really, really dig it, I dig it. I really, really dig it. Oh, I-yi love it so-woh-woh. I dig it, I dig it. I really, really dig it. I wish it would never go-woh–woh-woh. I See the Light All those days watching from the windows. All those years outside looking in. All that time never even knowing just how blind I've been. Now I'm here blinking in the starlight. Now I'm here - suddenly I see. Standing here it's oh so clear - I'm where I'm meant to be. (Refrain)And at last I see the light, and it's like the fog has lifted. And at last I see the light and it's like the sky is new. And it's warm and real and bright and the world has somehow shifted. All at once everything looks different now that I see you. All those days chasing down a daydream. All those years living in a blur. All that time never truly seeing things the way they were. Now she's here shining in the starlight. Now she's here - suddenly I know. If she's here it's crystal clear - I'm where I'm meant to go. Refrain Whacky Do Re Mi So mi la so mi, so mi la so mi Do – I make my cookies out of dough. -

|||GET||| Doctor Sleep a Novel 1St Edition

DOCTOR SLEEP A NOVEL 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE Stephen King | 9781476727653 | | | | | Doctor Sleep : A Novel by Stephen King (2013, Hardcover) First Printing. Not only does this story stand on its own, it manages to magnify the supernatural quality that first drew us to young Danny, expanding its mystery and its intensity in a way that might even reach beyond this book into the rest of the King-iverse About this Item: Hodder Doctor Sleep A Novel 1st edition, Skip to main content. About this product. Views Read Edit View history. The True Knot members wander across the United States and periodically feed on "steam", a psychic essence produced when the people who possess the shining die in pain. Condition: Fine. Seller Image. They look harmless - mostly old, lots of polyester, and married to their RVs. First Trade Edition. Packaging should be the same as what is found in a retail store, unless the item is handmade or was packaged by the manufacturer in non-retail packaging, such as an unprinted box or plastic bag. Most relevant reviews See all 45 reviews. Dust Jacket Condition: Dust Jacket. Book has clean and bright contents. Book Category. Book Description Scribner, What ever happened to Danny Torrance? Clean, tight and bright. With empathetic characters and descriptive atmosphere of the mind as on ly KIng can producethis novel works grandly and with the same creepy nuances as The Shining. What the novel lacks in brute fright, though, it makes up for with more subtle pleasures". Beautifully signed by Stephen King and illustrators at limitation page: "This special signed edition of Doctor Sleep is limited to numbered copies. -

The Shining - King and Kubrick Would 0 Be Proud!

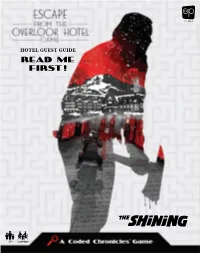

HOTEL GUEST GUIDE READ ME FIRST! Welcome to the Overlook Hotel Danny and Wendy need your help to escape! Something malevolent has sunk its claws into the very soul of Jack Torrance and it’s up to you to help his family escape from the Overlook Hotel before he finds them and does something unspeakable. Take on the roles of Wendy and Danny Torrance as you learn more about the twisted history of the sinister hotel. Can you keep your wits about you and solve the mysteries of the Overlook Hotel? Before looking at any other contents in this box, READ THIS HOTEL GUEST GUIDE! CONTENTS 4 Journals, 4 Room Tiles, 44 Clue Cards, 2 Character Standees, 11 Secret Envelopes, 1 Hotel Guest Guide 1 1 101 103 104 Wendy Torrance 1000-1999 105 COMPOSITION 101 BOOK Wendy Torrance 13 2000-2999Dan © & ™ WBEI. (s20) ny Torr 3000-4999 ance ROOM TILE 1 108 106 © & ™ WBEI. (s20) 1 Visitor Room Tiles Clue Cards 5000-9999 Book EnvelopeEnvelope 1 2 Do not open until instructed. Colorado Rockies, Colorado Envelope 3 Colorado Rockies, Colorado © & ™ WBEI. (s20)Do not open until instructed. Colorado Rockies, Colorado Colorado Rockies, Colorado Do not open until instructed. © & ™ WBEI. (s20) Envelope 4 Journals © & ™ WBEI.Do (s20) not open until instructed. © & ™ WBEI. (s20) 2 Secret Envelopes Character Standees SETUP 1. Hand out the Journals between as many different players as possible so that more people can participate in looking up results. 2. Place the stack of Room Tiles face-down. 3. Place the deck of Clue Cards face-down in numerical order next to the Room Tiles. -

Комментарии И Словарь О.Н. Прокофьевой УДК 811.111(075) ББК 81.2 Англ-9 К41 Stephen King the SHINING Дизайн Обложки А.И

Комментарии и словарь О.Н. Прокофьевой УДК 811.111(075) ББК 81.2 Англ-9 К41 Stephen King THE SHINING Дизайн обложки А.И. Орловой Печатается с разрешения издательства Doubleday, an imprint of h e Knopf Doubleday Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Grateful acknowledgment is made to the following for permission to reprint previously published material: Alfred Publishing Co., Inc: Excerpt from “Twenty Flight Rock,” words and music by Ned Fairchild and Eddie Cochran. Copyright © 1957 renewed by Unichappell Music Inc. and Elvis Presley Music Inc. All rights on behalf of Elvis Presley Music Inc. administered by Unichappell Music Inc. All rights reserved. Reprinted by permission of Alfred Publishing Co., Inc. Hal Leonard Corporation: Excerpt from “Bad Moon Rising,” words and music by John Fogerty. Copyright © 1969 by Jondora Music, copyright renewed. International copyright secured; excerpt from “Call Me (Come Back Home),” words and music by Willie Mitchell, Al Green and Al Jackson, Jr. Copyright © 1973 by Irving Music, Inc., Al Green Music, Inc. and Al Jackson, Jr. Music. Copyright renewed. All rights for Al Green Music, Inc. controlled and administered by Irving Music, Inc. All rights for Al Jackson Jr. Music administered by Bug Music. All rights reserved. Reprinted by permission of Hal Leonard Corporation. Sony/ATV Music Publishing LLC: Excerpt from “Your Cheatin’ Heart” by Hank Williams, Sr. Copyright © 1951 by Sony/ATV Music Publishing LLC. All rights administered by Sony/ATV Music Publishing LLC, 8 Music Square West, Nashville, TN 37203. All rights reserved. Reprinted by permission of Sony/ATV Music Publishing LLC. Кинг, Стивен.