The Irrational Ape: Why Flawed Logic Puts Us All at Risk and How Critical

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Week & Date Syllabus for ASTR 1200

Week & Date Syllabus for ASTR 1200 Doug Duncan, Fall 2018 *** be sure to read "About this Course" on the class Desire 2 Learn website*** The Mastering Astronomy Course Code is there, under "Mastering Astronomy" Do assigned readings BEFORE TUESDAYS - there will be clicker questions on the reading. Reading assignments are pink on this syllabus. Homework will usually be assigned on Tuesday, due the following Tuesday Read the textbook Strategically! Focus on answering the "Learning Goals." Week 1 Introductions. The amazing age of discovery in which we live. Aug. 28 The sky and its motions. My goals for the course. What would you like to learn about? What do I expect from you? Good news/bad news. Science vs. stories about science. This is a "student centered" class. I'm used to talking (Public Radio career). Here you talk too. Whitewater river analogy: If you don't want to paddle, don't get in the boat. Grading. Cheating. Clickers and why we use them. Homework out/in Fridays. Tutorials. Challenges. How to do well in the class. [reading clicker quiz] Why employers love to hire graduates of this class! Read bottom syllabus; "Statement of Expectations" for Arts & Sciences Classes" Policy on laptops and cell phones. Registrations: Clickers, Mastering Astronomy. Highlights of what the term will cover -- a bargain tour of the universe Bloom's Taxonomy of Learning What can we observe about the stars? Magnitude and color. Visualizing the Celestial Sphere - extend Earth's poles and equator to infinity! Visualizing the local sky: atltitude and azimuth Homeworks #1, How to Use Mastering Astronomy, due Sept. -

HUNG LIU: OFFERINGS January 23-March 17, 2013

PRESS RELEASE FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contacts: December 12, 2012 Maysoun Wazwaz Mills College Art Museum, Program Manager 510.430.3340 or [email protected] Mills College Art Museum Announces HUNG LIU: OFFERINGS January 23-March 17, 2013 Oakland, CA—December 12, 2012. The Mills College Art Museum is pleased to present Hung Liu: Offerings a rare opportunity to experience two of the Oakland-based artist’s most significant large- scale installations: Jiu Jin Shan (Old Gold Mountain) (1994) and Tai Cang—Great Granary (2008). Hung Liu: Offerings will be on view from January 23 through March 17, 2013. The opening reception takes place on Wednesday, January 23, 2013 from 6:00–8:00 pm and free shuttle service will be provided from the MacArthur Bart station during the opening. Recognized as America's most important Chinese artist, Hung Liu’s installations have played a central role in her work throughout her career. In Jiu Jin Shan (Old Gold Mountain), over two hundred thousand fortune cookies create a symbolic gold mountain that engulfs a crossroads of railroad tracks running beneath. The junction where the tracks meet serves as both a crossroads and 1 terminus, a visual metaphor of the cultural intersection of East and West. Liu references not only the history of the Chinese laborers who built the railroads to support the West Coast Gold Rush, but also the hope shared among these migrant workers that they could find material prosperity in the new world. The Mills College Art Museum is excited to be the first venue outside of China to present Tai Cang— Great Granary. -

Hamilton's Forgotten Epidemics

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Ch2olera: Hamilton’s Forgotten Epidemics / D. Ann Herring and Heather T. Battles, editors. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-9782417-4-2 Print catalogue data is available from Library and Archives Canada, at www.collectionscanada.gc.ca Cover Image: Historical City of Hamilton. Published by Rice & Duncan in 1859, drawn by G. Rice. http://map.hamilton.ca/old hamilton.jpg Cover Design: Robert Huang Group Photo: Temara Brown Ch2olera Hamilton’s Forgotten Epidemics D. Ann Herring and Heather T. Battles, editors DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY McMASTER UNIVERSITY Hamilton, Ontario, Canada Contents FIGURES AND TABLES vii Introduction Ch2olera: Hamilton’s Forgotten Epidemics D. Ann Herring and Heather T. Battles 2 2 “From Time Immemorial”: British Imperialism and Cholera in India Diedre Beintema 8 3 Miasma Theory and Medical Paradigms: Shift Happens? Ayla Mykytey 18 4 ‘A Rose by Any Other Name’: Types of Cholera in the 19th Century Thomas Siek 24 5 Doesn’t Anyone Care About the Children? Katlyn Ferrusi 32 6 Changing Waves: The Epidemics of 1832 and 1854 Brianna K. Johns 42 7 Charcoal, Lard, and Maple Sugar: Treating Cholera in the 19th Century S. Lawrence-Nametka 52 iii 8 How Disease Instills Fear into a Population Jacqueline Le 62 9 The Blame Game Andrew Turner 72 10 Virulence Victims in Victorian Hamilton Jodi E. Smillie 80 11 On the Edge of Death: Cholera’s Impact on Surrounding Towns and Hamlets Mackenzie Armstrong 90 12 Avoid Cholera: Practice Cleanliness and Temperance Karolina Grzeszczuk 100 13 New Rules to Battle the Cholera Outbreak Alexandra Saly 108 14 Sanitation in Early Hamilton Nathan G. -

Signature Redacted Certified By: William Fjricchio Professor of Compa Ive Media Studies Thesis Supervisor Signature Redacted Accepted By

Manufacturing Dissent: Assessing the Methods and Impact of RT (Russia Today) by Matthew G. Graydon B.A. Film University of California, Berkeley, 2008 SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF COMPARATIVE MEDIA STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN COMPARATIVE MEDIA STUDIES AT THE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY JUNE 2019 C2019 Matthew G. Graydon. All rights reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. S~ri' t A Signature red acted Department of Comparative 6/ledia Studies May 10, 2019 _____Signature redacted Certified by: William fJricchio Professor of Compa ive Media Studies Thesis Supervisor Signature redacted Accepted by: MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE Professor of Comparative Media Studies _OF TECHNOLOGY Director of Graduate Studies JUN 1 12019 LIBRARIES ARCHIVES I I Manufacturing Dissent: Assessing the Methods and Impact of RT (Russia Today) by Matthew G. Graydon Submitted to the Department of Comparative Media Studies on May 10, 2019 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Comparative Media Studies ABSTRACT The state-sponsored news network RT (formerly Russia Today) was launched in 2005 as a platform for improving Russia's global image. Fourteen years later, RT has become a self- described tool for information warfare and is under increasing scrutiny from the United States government for allegedly fomenting unrest and undermining democracy. It has also grown far beyond its television roots, achieving a broad diffusion across a variety of digital platforms. -

South Trail Times

SOUTH TRAIL TIMES Volume 3 / Issue 9 SEPTEMBER EDITION: September, 2016 Bizarre and Unique Holidays Month: Classical Music Month Hispanic Heritage Month Fall Hat Month International Square Dancing Month National Blueberry Popsicle Month National Courtesy Month National Piano Month Chicken Month Baby Safety Month Little League Month Honey Month Self-Improvement Month Better Breakfast Month September, 2016 Daily Holidays, Special and Wacky Days: 1 Emma M. Nutt Day, the first woman telephone operator 2 International Bacon Day - Saturday before Labor Day---that’s my kind of day 2 VJ Day, WWII 3 Skyscraper Day 4 Newspaper Carrier Day 5 Be Late for Something Day 5 Cheese Pizza Day 5 Labor Day First Monday of month 6 Fight Procrastination Day 6 Read a Book Day 7 National Salami Day 7 Neither Rain nor Snow Day 8 International Literacy Day 8 National Date Nut Bread Day - or December 22!? 8 Pardon Day 9 Teddy Bear Day 10 Sewing Machine Day 10 Swap Ideas Day 11 911 Remembrance 11 Eid-Ul-Adha 11 Grandparent's Day - first Sunday after Labor Day 11 Make Your Bed Day 11 National Pet Memorial Day -second Sunday in September 11 No News is Good News Day 12 Chocolate Milk Shake Day 12 National Video Games Day - also see Video Games Day in July 13 Defy Superstition Day 13 Fortune Cookie Day 13 National Peanut Day 13 Positive Thinking Day 13 Uncle Sam Day - his image was first used in 1813 14 National Cream-Filled Donut Day 15 Make a Hat Day 15 Felt Hat Day - On this day, men traditionally put away their felt hats. -

The Life of High School Coaches

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies, Jack N. Averitt College of Fall 2020 Between and Behind the Lines: The Life of High School Coaches Mary Davis Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/etd Part of the Curriculum and Instruction Commons, Other Education Commons, and the Secondary Education Commons Recommended Citation Davis, M.K. (2020). Between and behind the lines: The life of high school coaches This dissertation (open access) is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies, Jack N. Averitt College of at Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BETWEEN AND BEHIND THE LINES: THE LIFE OF HIGH SCHOOL COACHES by MARY K. DAVIS (Under the Direction of John Weaver) ABSTRACT In this study, I write about the emotional journey of high school athletic coaches’ experiences as they move through their day as teachers, coaches, and spouses/parents. The examination of the emotions and transitions high school coaches experience has been largely unresearched. There have been examinations of teachers, the impact coaches have on athletes, and a coach as a parent, but there is not extensive research on all three roles experienced by one person. High school athletics is a tremendous part of high school, and coaches have a tremendous impact not only on their players, but on the students they teach in the classroom as well. Coaches are often more visible and identifiable than the administration. -

Contemporary Popular Beliefs in Japan

Hugvísindasvið Contemporary popular beliefs in Japan Ritgerð til B.A.-prófs Lára Ósk Hafbergsdóttir September 2010 Háskóli Íslands Hugvísindadeild Japanskt mál og menning Contemporary popular beliefs in Japan Ritgerð til B.A.-prófs Lára Ósk Hafbergsdóttir Kt.: 130784-3219 Leiðbeinandi: Gunnella Þorgeirsdóttir September 2010 Abstract This thesis discusses contemporary popular beliefs in Japan. It asks the questions what superstitions are generally known to Japanese people and if they have any affects on their behavior and daily lives. The thesis is divided into four main chapters. The introduction examines what is normally considered to be superstitious beliefs as well as Japanese superstition in general. The second chapter handles the methodology of the survey written and distributed by the author. Third chapter is on the background research and analysis which is divided into smaller chapters each covering different categories of superstitions that can be found in Japan. Superstitions related to childhood, death and funerals, lucky charms like omamori and maneki neko and various lucky days and years especially yakudoshi and hinoeuma are closely examined. The fourth and last chapter contains the conclusion and discussion which covers briefly the results of the survey and what other things might be of interest to investigate further. Table of contents 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................... 3 1.1 What is superstition? ............................................................................................... -

The Rise and Fall of the Wessely School

THE RISE AND FALL OF THE WESSELY SCHOOL David F Marks* Independent Researcher Arles, Bouches-du-Rhône, Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur, 13200, France *Address for correspondence: [email protected] Rise and Fall of the Wessely School THE RISE AND FALL OF THE WESSELY SCHOOL 2 Rise and Fall of the Wessely School ABSTRACT The Wessely School’s (WS) approach to medically unexplained symptoms, myalgic encephalomyelitis and chronic fatigue syndrome (MUS/MECFS) is critically reviewed using scientific criteria. Based on the ‘Biopsychosocial Model’, the WS proposes that patients’ dysfunctional beliefs, deconditioning and attentional biases cause illness, disrupt therapies, and lead to preventable deaths. The evidence reviewed here suggests that none of the WS hypotheses is empirically supported. The lack of robust supportive evidence, fallacious causal assumptions, inappropriate and harmful therapies, broken scientific principles, repeated methodological flaws and unwillingness to share data all give the appearance of cargo cult science. The WS approach needs to be replaced by an evidence-based, biologically-grounded, scientific approach to MUS/MECFS. 3 Rise and Fall of the Wessely School Sickness doesn’t terrify me and death doesn’t terrify me. What terrifies me is that you can disappear because someone is telling the wrong story about you. I feel like that’s what happened to all of us who are living this. And I remember thinking that nobody’s coming to look for me because no one even knows that I went missing. Jennifer Brea, Unrest, 20171. 1. INTRODUCTION This review concerns a story filled with drama, pathos and tragedy. It is relevant to millions of seriously ill people with conditions that have no known cause or cure. -

Sorting the Healthy Diet Signal from the Social Media Expert Noise: Preliminary Evidence from the Healthy Diet Discourse on Twitter

Sorting the Healthy Diet Signal from the Social Media Expert Noise: Preliminary Evidence from the Healthy Diet Discourse on Twitter Theo Lynn∗, Pierangelo Rosati∗, Guto Leoni Santosy, Patricia Takako Endoz ∗Irish Institute of Digital Business, Dublin City University, Ireland yUniversidade Federal de Pernambuco, Brazil zUniversidade de Pernambuco, Brazil ftheo.lynn, [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract—Over 2.8 million people die each year from being obese, a largely preventable disease [2]. In addition to loss overweight or obese, a largely preventable disease. Raised body of life, obesity places a substantial burden on society and weight indexes are associated with higher risk of cardiovascular health systems, and contributes to lost economic productivity diseases, diabetes, musculoskeletal disorders, and some cancers. Social media has fundamentally changed the way we commu- and reduced quality of life [3]. Public health education and nicate, collaborate, consume, and create content. The ease with promotion of healthy diets combined with physical activity is which content can be shared has resulted in a rapid increase in a critical public health strategy in in the mitigation of adverse the number of individuals or organisations that seek to influence affects associated with being overweight or obese. opinion and the volume of content that they generate. The Throughout the world, the Internet is a major source of nutrition and diet domain is not immune to this phenomenon. Unfortunately, from a public health perspective, many of these public health information [4]–[6]. Social media has funda- “influencers” may be poorly qualified to provide nutritional or mentally changed the way we communicate, collaborate, con- dietary guidance and advice given may be without accepted sume, and create content [7]. -

Psychic’ Sally Morgan Scuffles with Toward a Cognitive Psychology U.K

Science & Skepticism | Randi’s Escape Part II | Martin Gardner | Monster Catfish? | Trent UFO Photos the Magazine for Science and Reason Vol. 39 No. 1 | January/February 2015 Why the Supernatural? Why Conspiracy Ideas? Modern Geocentrism: Pseudoscience in Astronomy Flaw and Order: Criminal Profiling Sylvia Browne’s Art and Science FBI File More Witch Hunt Murders INTRODUCTORY PRICE U.S. and Canada $4.95 Published by the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry C I Ronald A. Lindsay, President and CEO Massimo Polidoro, Research Fellow Bar ry Karr, Ex ec u tive Di rect or Benjamin Radford, Research Fellow Joe Nickell, Senior Research Fellow Richard Wiseman, Research Fellow www.csicop.org James E. Al cock*, psy chol o gist, York Univ., Tor on to David H. Gorski, cancer surgeon and re searcher at Astronomy and director of the Hopkins Mar cia An gell, MD, former ed i tor-in-chief, Barbara Ann Kar manos Cancer Institute and chief Observatory, Williams College New Eng land Jour nal of Med i cine of breast surgery section, Wayne State University John Pau los, math e ma ti cian, Tem ple Univ. School of Medicine. Kimball Atwood IV, MD, physician; author; Clifford A. Pickover, scientist, au thor, editor, Newton, MA Wendy M. Grossman, writer; founder and first editor, IBM T.J. Watson Re search Center. Steph en Bar rett, MD, psy chi a trist; au thor; con sum er The Skeptic magazine (UK) Massimo Pigliucci, professor of philosophy, ad vo cate, Al len town, PA Sus an Haack, Coop er Sen ior Schol ar in Arts and City Univ. -

California Folklore Miscellany Index

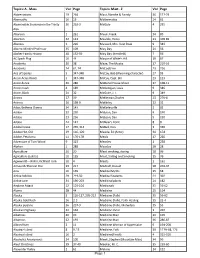

Topics: A - Mass Vol Page Topics: Mast - Z Vol Page Abbreviations 19 264 Mast, Blanche & Family 36 127-29 Abernathy 16 13 Mathematics 24 62 Abominable Snowman in the Trinity 26 262-3 Mattole 4 295 Alps Abortion 1 261 Mauk, Frank 34 89 Abortion 22 143 Mauldin, Henry 23 378-89 Abscess 1 226 Maxwell, Mrs. Vest Peak 9 343 Absent-Minded Professor 35 109 May Day 21 56 Absher Family History 38 152-59 May Day (Kentfield) 7 56 AC Spark Plug 16 44 Mayor of White's Hill 10 67 Accidents 20 38 Maze, The Mystic 17 210-16 Accidents 24 61, 74 McCool,Finn 23 256 Ace of Spades 5 347-348 McCoy, Bob (Wyoming character) 27 93 Acorn Acres Ranch 5 347-348 McCoy, Capt. Bill 23 123 Acorn dance 36 286 McDonal House Ghost 37 108-11 Acorn mush 4 189 McGettigan, Louis 9 346 Acorn, Black 24 32 McGuire, J. I. 9 349 Acorns 17 39 McKiernan,Charles 23 276-8 Actress 20 198-9 McKinley 22 32 Adair, Bethena Owens 34 143 McKinleyville 2 82 Adobe 22 230 McLean, Dan 9 190 Adobe 23 236 McLean, Dan 9 190 Adobe 24 147 McNear's Point 8 8 Adobe house 17 265, 314 McNeil, Dan 3 336 Adobe Hut, Old 19 116, 120 Meade, Ed (Actor) 34 154 Adobe, Petaluma 11 176-178 Meals 17 266 Adventure of Tom Wood 9 323 Measles 1 238 Afghan 1 288 Measles 20 28 Agriculture 20 20 Meat smoking, storing 28 96 Agriculture (Loleta) 10 135 Meat, Salting and Smoking 15 76 Agwiworld---WWII, Richfield Tank 38 4 Meats 1 161 Aimee McPherson Poe 29 217 Medcalf, Donald 28 203-07 Ainu 16 139 Medical Myths 15 68 Airline folklore 29 219-50 Medical Students 21 302 Airline Lore 34 190-203 Medicinal plants 24 182 Airplane -

10 Fallacies and Examples Pdf

10 fallacies and examples pdf Continue A: It is imperative that we promote adequate means to prevent degradation that would jeopardize the project. Man B: Do you think that just because you use big words makes you sound smart? Shut up, loser; You don't know what you're talking about. #2: Ad Populum: Ad Populum tries to prove the argument as correct simply because many people believe it is. Example: 80% of people are in favor of the death penalty, so the death penalty is moral. #3. Appeal to the body: In this erroneous argument, the author argues that his argument is correct because someone known or powerful supports it. Example: We need to change the age of drinking because Einstein believed that 18 was the right age of drinking. #4. Begging question: This happens when the author's premise and conclusion say the same thing. Example: Fashion magazines do not harm women's self-esteem because women's trust is not damaged after reading the magazine. #5. False dichotomy: This misconception is based on the assumption that there are only two possible solutions, so refuting one decision means that another solution should be used. It ignores other alternative solutions. Example: If you want better public schools, you should raise taxes. If you don't want to raise taxes, you can't have the best schools #6. Hasty Generalization: Hasty Generalization occurs when the initiator uses too small a sample size to support a broad generalization. Example: Sally couldn't find any cute clothes in the boutique and couldn't Maura, so there are no cute clothes in the boutique.