The Condemned Sons in the Blessing of Jacob (Gen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Order and Significance of the Sealed Tribes of Revelation 7:4-8

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Master's Theses Graduate Research 2011 The Order and Significance of the Sealed ribesT of Revelation 7:4-8 Michael W. Troxell Andrews University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/theses Recommended Citation Troxell, Michael W., "The Order and Significance of the Sealed ribesT of Revelation 7:4-8" (2011). Master's Theses. 56. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/theses/56 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your interest in the Andrews University Digital Library of Dissertations and Theses. Please honor the copyright of this document by not duplicating or distributing additional copies in any form without the author’s express written permission. Thanks for your cooperation. ABSTRACT THE ORDER AND SIGNIFICANCE OF THE SEALED TRIBES OF REVELATION 7:4-8 by Michael W. Troxell Adviser: Ranko Stefanovic ABSTRACT OF GRADUATE STUDENT RESEARCH Thesis Andrews University Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary Title: THE ORDER AND SIGNIFICANCE OF THE SEALED TRIBES OF REVELATION 7:4-8 Name of researcher: Michael W. Troxell Name and degree of faculty adviser: Ranko Stefanovic, Ph.D. Date completed: November 2011 Problem John’s list of twelve tribes of Israel in Rev 7, representing those who are sealed in the last days, has been the source of much debate through the years. This present study was to determine if there is any theological significance to the composition of the names in John’s list. -

Israel's Conquest of Canaan: Presidential Address at the Annual Meeting, Dec

Israel's Conquest of Canaan: Presidential Address at the Annual Meeting, Dec. 27, 1912 Author(s): Lewis Bayles Paton Reviewed work(s): Source: Journal of Biblical Literature, Vol. 32, No. 1 (Apr., 1913), pp. 1-53 Published by: The Society of Biblical Literature Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3259319 . Accessed: 09/04/2012 16:53 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The Society of Biblical Literature is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of Biblical Literature. http://www.jstor.org JOURNAL OF BIBLICAL LITERATURE Volume XXXII Part I 1913 Israel's Conquest of Canaan Presidential Address at the Annual Meeting, Dec. 27, 1912 LEWIS BAYLES PATON HARTFORD THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY problem of Old Testament history is more fundamental NO than that of the manner in which the conquest of Canaan was effected by the Hebrew tribes. If they came unitedly, there is a possibility that they were united in the desert and in Egypt. If their invasions were separated by wide intervals of time, there is no probability that they were united in their earlier history. Our estimate of the Patriarchal and the Mosaic traditions is thus conditioned upon the answer that we give to this question. -

And This Is the Blessing)

V'Zot HaBerachah (and this is the blessing) Moses views the Promised Land before he dies את־ And this is the blessing, in which blessed Moses, the man of Elohim ְ ו ז ֹאת Deuteronomy 33:1 Children of Israel before his death. C-MATS Question: What were the final words of Moses? These final words of Moses are a combination of blessing and prophecy, in which he blesses each tribe according to its national responsibilities and individual greatness. Moses' blessings were a continuation of Jacob's, as if to say that the tribes were blessed at the beginning of their national existence and again as they were about to begin life in Israel. Moses directed his blessings to each of the tribes individually, since the welfare of each tribe depended upon that of the others, and the collective welfare of the nation depended upon the success of them all (Pesikta). came from Sinai and from Seir He dawned on them; He shined forth from יהוה ,And he (Moses) said 2 Mount Paran and He came with ten thousands of holy ones: from His right hand went a fiery commandment for them. came to Israel from Seir and יהוה ?present the Torah to the Israelites יהוה Question: How did had offered the Torah to the descendants of יהוה Paran, which, as the Midrash records, recalls that Esau, who dwelled in Seir, and to the Ishmaelites, who dwelled in Paran, both of whom refused to accept the Torah because it prohibited their predilections to kill and steal. Then, accompanied by came and offered His fiery Torah to the Israelites, who יהוה ,some of His myriads of holy angels submitted themselves to His sovereignty and accepted His Torah without question or qualification. -

REUBEN AHRONI an Appreciation

REUBEN AHRONI An Appreciation by Y edida Kalfon Stillman State University of New York, Binghamton It is a very pleasant task, indeed, to write a few words of appreciation about Reuben Ahroni for this volume which is dedicated to him. I have not only read many of his scholarly publications in English and Hebrew, and have even reviewed one his books, but I have also had the pleasure and privilege of knowing this learned, modest, and gentle person as a colleague and a friend. His innate sweetness and genuine, unfeigned humility have endeared Reuben Ahroni to all who know him. I, in particular, have always felt a certain kinship with Reuben due to our shared backgrounds as Jews from Arab countries who grew up in the young State of Israel, completed our advanced studies in the United States, and have made our academic careers in this country. Reuben Ahroni hailed from the ancient Jewish community of southern Arabia, a community whose origins go back to biblical times. He was born to a large family of eleven in the British Crown Colony of Aden. The Adeni community combined the religious traditionalism of their Yemenite brethren in the interior with a modem world outlook fostered by modern education under the British aegis. Like most Adeni Jews, Reuben's family had strong Zionist sympathies, and as a boy, he was active in a labor-oriented Zionist youth group. At the age of eleven, Reuben experienced firsthand the devestation that engulfed Adeni Jewry when from December 2 to 4, 1947, shortly after the United Nations voted to partition Palestine, anti-Jewish riots broke out that left eighty-two Jews dead, a similar number injured, and the synagogue, the two schools, and hundreds of Jewish homes and most Jewish businesses destroyed. -

Genesis: Yesterday’S Answers to Today’S Problems

Genesis: Yesterday’s Answers to Today’s Problems. Bible Study Questions: Chapter 1: 1) How does Matthew 19:4 help us to identify when the beginning of time was? _________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________ 2) The word “bara” means to create out of nothing and is found in the first verse of Genesis. When is the next time this word is used in chapter 1? _________________________________________________________________________________________ 3) If the sun isn’t created until the 4th day of creation what can the light of day one be according to other Scriptures? _________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________ 4) What evidence is there of God’s energizing power at creation? _________________________________________________________________________________________ How does this connect with the believer today? _________________________________________________________________________________________ 5) Where do we find the Trinity in the first three verses of Genesis? _________________________________________________________________________________________ 6) Why could there be no death before the creation of man? - _________________________________________________________________________________________ 7) How can there be an evening and morning on day one, two and three, if the -

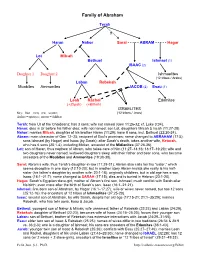

Family of Abraham

Family of Abraham Terah ? Haran Nahor Sarai - - - - - ABRAM - - - - - Hagar Lot Milcah Bethuel Ishmael (1) ISAAC (2) Daughter 1 Daughter 2 Ishmaelites (12 tribes / Arabs) Laban Rebekah Moabites Ammonites JACOB (2) Esau (1) Leah Rachel Edomites (+Zilpah) (+Bilhah) ISRAELITES Key: blue = men; red = women; (12 tribes / Jews) dashes = spouses; arrows = children Terah: from Ur of the Chaldeans; has 3 sons; wife not named (Gen 11:26-32; cf. Luke 3:34). Haran: dies in Ur before his father dies; wife not named; son Lot, daughters Milcah & Iscah (11:27-28). Nahor: marries Milcah, daughter of his brother Haran (11:29); have 8 sons, incl. Bethuel (22:20-24). Abram: main character of Gen 12–25; recipient of God’s promises; name changed to ABRAHAM (17:5); sons Ishmael (by Hagar) and Isaac (by Sarah); after Sarah’s death, takes another wife, Keturah, who has 6 sons (25:1-4), including Midian, ancestor of the Midianites (37:28-36). Lot: son of Haran, thus nephew of Abram, who takes care of him (11:27–14:16; 18:17–19:29); wife and two daughters never named; widowed daughters sleep with their father and bear sons, who become ancestors of the Moabites and Ammonites (19:30-38). Sarai: Abram’s wife, thus Terah’s daughter-in-law (11:29-31); Abram also calls her his “sister,” which seems deceptive in one story (12:10-20); but in another story Abram insists she really is his half- sister (his father’s daughter by another wife; 20:1-18); originally childless, but in old age has a son, Isaac (16:1–21:7); name changed to SARAH (17:15); dies and is buried in Hebron (23:1-20). -

DAF DITTY SHABBES 156- Siyum Masechta

DAF DITTY SHABBES 156 Talmudic Astrology Zodiac in a 6th-century synagogue at Beth Alpha, Israel. “A learned and cultured man of those times, could not reject the science of Astrology, 1 a science recognized and acknowledged by all the civilized ancient world” Saul Lieberman 1 1 Rabbi Ḥanina said to his students who heard all this: Go and tell the son of Leiva’i, Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi: It is not the constellation of the day of the week that determines a person’s nature; rather, it is the constellation of the hour that determines his nature. One who was born under the influence of the sun will be a radiant person; he will eat from his own resources and drink from his own resources, and his secrets will be exposed. If he steals, he will not succeed, because he will be like the sun that shines and is revealed to all. One who was born under the influence of Venus will be a rich and promiscuous person. What is the reason for this? Because fire was born during the hour of Venus, he will be subject the fire of the evil inclination, which burns perpetually. 2 One who was born under the influence of Mercury will be an enlightened and expert man, because Mercury is the sun’s scribe, as it is closest to the sun. One who was born under the influence of the moon will be a man who suffers pains, who builds and destroys, and destroys and builds. He will be a man who eats not from his own resources and drinks not from his own resources, and whose secrets are hidden. -

List of Enslaved Recorded in Commonplace Book.Xlsx

List of Enslaved Compiled from Notes in the Hite Family Commonplace Book (1776‐1859) (Virginia Historical Society: Hite Family Papers MssIH637535a‐40) ADDITIONAL NOTE TAKEN FROM POSSIBLE DUPLICATE ADDITIONAL NOTE MADE RECORD IN NAME (MOTHER'S NAME) BIRTHDATE NOTE MADE IN COMMONPLACE BOOK IN COMMONPLACE BOOK COMMONPLACE BOOK Primus (not given in) 1754 Run Away Ned 1758 Dead (noted as having) "had the Chloe 1760 Purchased of (illegible) cost 140,0,0 measles" Frank 1767 Gave George Hite 80 l for him Abba 1769 Received in Exchange with George Hite Frank 1769 Bought of Pisothic Charlotte 1770 Bought from William Elsey Hannah 1773 Purchased of Buck Bought of John Buck Nelly 1774 Purchased of Holmes, Dead Bought of Judah Holmes Frederick 1775 (bought of Booth) Nancy (Marjory's) 1777 Dead Sarah 1778 Bought of W.P.F 2/6/09 for 90,0,0 Tom 1778 Nancy 1779 Purchased of Grey, Dead Patrick 1782 Purchased of Grey John (Carpenter) 1785 Bought of Phil. Slaugh. Gave to Madison Sam (Milly's) 1787 Philis 1788 Exch.Rachel & Issac for Philis and 2 kids Anthony (Milly's) 1789 Prissy 1790 Purchased of Grey Unknown Name 1790 Bought of William P. Flood, 2/6/09 for 100, Name Judah and Dead 1836 Judy 1794 Dead and Purchased of Abraham Bowman (noted as having) "had the Betty & her children 1795 Purchased of (illegible) cost 140,0,0 measles" Betty (Truelove) 1795 Dead 1 List of Enslaved Compiled from Notes in the Hite Family Commonplace Book (1776‐1859) (Virginia Historical Society: Hite Family Papers MssIH637535a‐40) ADDITIONAL NOTE TAKEN FROM POSSIBLE DUPLICATE ADDITIONAL NOTE MADE RECORD IN NAME (MOTHER'S NAME) BIRTHDATE NOTE MADE IN COMMONPLACE BOOK IN COMMONPLACE BOOK COMMONPLACE BOOK George (Sarah's) 1798 Bought of W.P.F. -

The Blessing of Moses in Deuteronomy 33— Logotechnical Analysis Guidelines Please Read the General Introduction and the Introduction to the Embedded Hymns

2. The Blessing of Moses in Deuteronomy 33— Logotechnical Analysis Guidelines Please read the General Introduction and the Introduction to the Embedded Hymns. For common features found in the numerical analysis charts, see the "Key to the charts". The Blessing of Moses in its Literary Context As I have shown elsewhere, the Blessing of Moses was secondarily incorporated into the book at a stage when the concluding chapters were already finalized and rounded-off. It appeared that Deuteronomy 31-34, without the Blessing, is a skillfully designed, meticulously constructed numerical composition, in which the divine name numbers 17 and 26 have consistently been woven into the fabric of the text. This is particularly evident in the number of words in the different sections and more particularly in the speeches by Moses and YHWH, as revealed by the logotechnical analysis. The composition of the Blessing was in all likelihood inspired by the Blessing of Jacob in Genesis 49. In fact, Jacob is explicitly mentioned in 33:4, 10, and 28, which hooks on to 32:9. Its purpose was obviously to boost the function of the Song of Moses as his Farewell Address on the eve of the occupation of the land, which it anticipates in a special way. Two crucial themes link the Blessing not only to the Song of Moses, but also to the other poetic stepping-stones in the Story of Ancient Israel (Genesis-Kings): YHWH’s incomparability and his triumphant manifestation in saving his people and establishing them in their land. For YHWH’s incomparability, compare 33:26 with Deut. -

Favoritefavorite Sonson 9 Genesis 37; Patriarchs and Prophets, Pp

Lesson FavoriteFavorite SonSon 9 Genesis 37; Patriarchs and Prophets, pp. 208-212 s there anything that you really wish you him with them when they went somewhere. I had? Have you ever wanted it so badly that They didn’t want to be around him. The Bible it made you angry because someone else had it says they hated him. and you didn’t? Joseph was Jacob’s favorite son. Their Ten boys wanted what their brother had. They father always gave him the best presents. were so jealous of him that they planned something When father Jacob made Joseph a colorful terrible. new coat, all the brothers were jealous. They didn’t think Joseph deserved nicer things than oseph had 11 brothers—10 older and they got. J one younger. The older brothers did Joseph’s brothers also thought he was not like him. They probably left him out of the proud, which made them even angrier. Once games they played. They probably didn’t take God gave Joseph a dream that he and his brothers had been cutting stalks of grain and tying them into sheaves. Suddenly all of his brothers’ sheaves bowed toward his. Another time he dreamed that the sun, moon, and 11 stars had bowed down to him. His father asked, “Does this mean you will even rule over your mother and me someday?” Jacob’s older sons often took their father’s sheep far away from home to find good pasture. They enjoyed being out on their own with no little brother to annoy them. -

The Blessing of Moses (Deut 33:2–29)

CHAPTER TEN THE BLESSING OF MOSES (Deut 33:2–29) The Blessing of Moses is one of the most difficult texts not only in the present corpus, but in Hebrew Bible in general:1 its textual conditions are much debated;2 there are many unclear and unique words.3 It is conven- tionally accepted that this literary composition is not homogeneous, and consists of the hymnal framework in vv. 2–5 and 26–29 (with some possible insertions in the middle of the composition) and the collection of tribal sayings (6–25).4 Without challenging this historical-literary approach to the problem of its composition, the discursive analysis of the text reveals a structure that is more complicated than the two-fold distinction between a hymnal framework and a collection of tribal sayings; moreover, there is a certain correlation between the framework and the collection of sayings in regard to the discourse structure, as will be shown below.5 10.1. Introduction: Discourse Structure 10.1.1. The Communication Participants An interesting discourse feature in the Blessing of Moses is the total lack of 1cs reference to the speaker, even within the elements of the conver- sational framework, which are, however, marked with the 2nd-person 1 Cf. Beyerle 1998: 215: “the Blessing of Moses (Deut 33) is among the most difficult and puzzling texts in the OT”. See also his review in Beyerle 1997: 1–7. 2 See Fuller 1993; Duncan 1995; Beyerle 1998; McCarthy 2002; 2007: 155–67. 3 Cf. Tigay 1996: 547 nn. 1 and 2 (in Excursus 33) or Rendsburg 2009a. -

Joseph's Brothers: Guilt, Repentance, Remorse

Joseph’s Brothers: Guilt, Repentance, Remorse Parashat Mikeitz, Genesis 41:1-44:17 & Parashat Va-yigash, Genesis 44:18-47:27 By Mark Greenspan ―Repentance‖ by David Lincoln (pp. 412) in The Observant Life Introduction One of the central themes in living a spiritual life is t‟shuvah, repentance. More than just an idea, t‟shuvah is a way of life: we are constantly striving to return to a fuller and more whole vision of self. While we tend to focus on themes relating to repentance on the High Holy Days, t‟shuvah is a year-round concern. This is best reflected in the words of Rabbi Eliezer who taught: ―Repent one day before your death.‖ When his students asked, ―Does one know on what day he will die?‖ Rabbi Eliezer answered, ―All the more reason one should repent today, lest one die tomorrow‖ (BT Shabbat 153a). T‟shuvah literally means ‗return.‘ To what does one return? How can one know when repentance (our own and that of others) is sincere? How is repentance before God different from repentance for harm caused to human beings? What role does Yom Kippur play in bringing about repentance? We gain some insight into the complexity of this unending process in the words of the sages: ―Yom Kippur atones for sins against God. Yom Kippur does not atone for sins against another human being until one has placated the person offended‖ (Mishnah Yoma 8:9). David Lincoln suggests that the Bible deals almost exclusively with communal rather than individual repentance. This may be true, but one can argue that the story of Joseph is a dramatic story of individual repentance.