Lyme's Battle with the Sea: Part 1: the Cobb Breakwater

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Congregational Chapel's Graveyard

https://www.lymeregismuseum.co.uk/research Congregational Chapel Coombe Street, Lyme Regis The Search for a Graveyard Graham Davies, July 2021 The Dinosaurland Fossil Museum in Coombe Street, Lyme Regis, occupies a grade I listed building, a former Congregational (more recently, United Reform) Chapel which closed its doors to religious services in 1985. The Congregational (Independent) Church was formed in Lyme in 1662 following the ejection of the vicar, the Rev A Short, for non-compliance with the Act of Uniformity. He subsequently held services in his own house in Church Street and elsewhere, but was constantly hounded by the authorities. He died in 1697. In 1734 the Rev J Whitty became the new minister and under his guidance a chapel was built in Coombe Street in 1755. Dinosaurland, June 2013 In 2012, research team members, Diane Shaw, Derek Perrey and Graham Davies reviewed the Museum’s Congregational Chapel archives. They found a reference to a ‘curious little graveyard’ on the Lynch, belonging to the Congregational Chapel. In 1841, on behalf of the Chapel, a piece of ground, with two cottages on it (ref 192, 1841 tithe map), situated on the Lynch, was purchased by Mr Theophilus B Goddard from Mr Fowler, of the Hart Inn, at a price of £250. Extensive alterations were made to the cottages, and the part to be used as the burial ground was walled off from the rest. Mr Goddard hoped the Church would repay him his £250 through rents, burial fees and subscriptions. Through lack of subscriptions, Mr Goddard was set free by the Church in 1873 to dispose of the cottages as he saw fit, leaving them the graveyard. -

Report-Back from Earth Festival Stakeholder Meetings Along The

Report-back from Earth Festival stakeholder meetings along the Jurassic Coast World Heritage Site November 2010 1 A series of three meetings were held in November 2012 in Lyme Regis, Lulworth and Portland to discuss the Jurassic Coast Earth festival, which will be taking place between 4 May and 9 September 2012. (The East Devon meeting was postponed due to severe weather warnings and is rescheduled for 13 January 2011.) The Jurassic Coast Earth Festival is being led by the Lyme Regis Development Trust, and these events were run with invaluable input by various members of the Jurassic Coast World Heritage Team – which is supporting the development and implementation of the Earth Festival. The aims of the meetings were to: communicate the themes and opportunities provided by the Jurassic Coast Earth Festival 2012 inspire participation in the festival and stimulate new initiatives create connections within and between communities along the Jurassic Coast These were attended by over 80 people, comprising artists and arts organisations, venues, museums, local authority officers, councillors, community initiatives, visitor centres, conservation organisations including the National Trust, Dorset and Devon AONB, Natural England, Countryside Rangers, schools, media and others. A preliminary website www.earthfestival2012.org has since been created which contains information on the scope and aims of the Earth Festival. This will be added to as soon as possible in order to incorporate information about key events in planning, as they emerge, as well as a ‘back end’ facility to enable networking and project development between various initiatives. Copies of main presentations are being emailed to participants and available to download from the website, as are Earth festival Project/Event planning Proformas. -

Conservation Status of the Rare Endemic Centaurium Tenuiflorum Subsp

British & Irish Botany 3(2): 161-167, 2021 Conservation status of the rare endemic Centaurium tenuiflorum subsp. anglicum, English Centaury (Gentianaceae) Elizabeth L. Downey¹, David A. Pearman², Timothy C.G. Rich³* ¹Wadeford, U.K., ²Truro, U.K., ³Cardiff, U.K. *Corresponding author: Timothy C.G. Rich: [email protected] This pdf constitutes the Version of Record published on 26th July 2021 Abstract The status of the rare English endemic Centaurium tenuiflorum subsp. anglicum, English Centaury, has been assessed from field surveys in 2020 and compared against previous population counts. In Dorset, 16 populations with c.25,815 plants occurred and there was no evidence of overall decline. It was not refound in one site in the Isle of Wight. The IUCN threat status is ‘Least Concern’. Keywords: England; IUCN threat status; Dorset; Isle of Wight Introduction Centaurium tenuiflorum subsp. anglicum T.C.G. Rich & McVeigh, English Centaury (Gentianaceae) is a rare endemic known from about 18 sites in v.c.9 (Dorset) and v.c.10 (Isle of Wight) in Southern England (Rich et al., 2019; Rich & McVeigh, 2019; Figs. 1-3). A short video describing the plant and its habitats is given by Rich (2020). The JNCC (2020) assessment of its IUCN (2001) threat status as ‘Least Concern’ was based on 1996-2002 data in Edwards & Pearman (2004). In 2020, all accessible populations were revisited to obtain up-to-date population counts. The aim of this short paper is to present the data and update the threat status. Methods In Dorset the entire coastline between St Gabriels and West Bay was checked from the base of the cliffs by E. -

Excursion to Lyme Regis, Easter, 1906

320 EXCURSION TO LYME REGIS, EASTER, 1906. pebbles and bed NO.3 seemed, however, to be below their place. The succession seemed, however,to be as above, and, if that be so, the beds below bed I are probably Bagshot Beds. "The pit at the lower level has been already noticed in our Proceedings; cj. H. W. Monckton and R. S. Herries 'On some Bagshot Pebble Beds and Pebble Gravel,' Proc. Ceol. Assoc., vol. xi, p. 13, at p. 22. The pit has been worked farther back, and the clay is now in consequence thicker. Less of the under lying sand is exposed than it was in June, 1888. "The casts of shells which occur in this sand were not abundant, but several were found by members of the party on a small heap of sand at the bottom of the pit." Similarly disturbed strata were again observed in the excavation for the new reservoir close by. A few minutes were then profitably spent in examining Fryerning Church, and its carved Twelfth Century font, etc. At the Spread Eagle a welcome tea awaited the party, which, after thanking the Director, returned by the 7.55 p.m. train to London. REFERENCES. Geological Survey Map, Sheet 1 (Drift). 1889. WHITAKER, W.-I< Geology of London," vol. i, pp. 259, 266. &c. 1889. MONCKTON, H. W., and HERRIES, R. S.-I< On Some Bagshot Pebble Beds and Pebble Gravel," Proc, Geo], Assoc., vol, xi, p. 13. 1904. SALTER, A. E.-" On the Superficial Deposits of Central and Southern England," Proc. Ceo!. Assoc., vol. -

The Future of Midlatitude Cyclones

Current Climate Change Reports https://doi.org/10.1007/s40641-019-00149-4 MID-LATITUDE PROCESSES AND CLIMATE CHANGE (I SIMPSON, SECTION EDITOR) The Future of Midlatitude Cyclones Jennifer L. Catto1 & Duncan Ackerley2 & James F. Booth3 & Adrian J. Champion1 & Brian A. Colle4 & Stephan Pfahl5 & Joaquim G. Pinto6 & Julian F. Quinting6 & Christian Seiler7 # The Author(s) 2019 Abstract Purpose of Review This review brings together recent research on the structure, characteristics, dynamics, and impacts of extratropical cyclones in the future. It draws on research using idealized models and complex climate simulations, to evaluate what is known and unknown about these future changes. Recent Findings There are interacting processes that contribute to the uncertainties in future extratropical cyclone changes, e.g., changes in the horizontal and vertical structure of the atmosphere and increasing moisture content due to rising temperatures. Summary While precipitation intensity will most likely increase, along with associated increased latent heating, it is unclear to what extent and for which particular climate conditions this will feedback to increase the intensity of the cyclones. Future research could focus on bridging the gap between idealized models and complex climate models, as well as better understanding of the regional impacts of future changes in extratropical cyclones. Keywords Extratropical cyclones . Climate change . Windstorms . Idealized model . CMIP models Introduction These features are a vital part of the global circulation and bring a large proportion of precipitation to the midlatitudes, The way in which most people will experience climate change including very heavy precipitation events [1–5], which can is via changes to the weather where they live. -

1 Sidmouth Road 1 Sidmouth Road Lyme Regis Bridport 10 Miles

1 Sidmouth Road 1 Sidmouth Road Lyme Regis Bridport 10 miles • Triple aspect sitting room. kitchen breakfast room with Rayburn. • Utility room. • Self-contained guest bedroom/annexe. • 3 further bedrooms and a family bathroom. • Stunning conservatory. • Substantial outbuilding. • Glorious views and a mature garden. Guide price £635,000 SITUATION AND AMENITIES 1 Sidmouth Road is situated close to the heart of the quaint and quirky Lyme Regis with its iconic Cobb wall and bustling town. Lyme is part of the stunning Jurassic Coast. The area has also been the inspiration for many famed novelists and playwrights, with John Fowles and Ann Jellicoe, to name but a few. The town has a thriving heart offering convenience and bespoke shopping of a surprising variety for a town of its size, as well as a number of renowned popular restaurants and hotels. The town's day to day amenities include banks, a health centre, churches, well regarded primary A unique detached home that has been improved upon over the and secondary schooling, library, museum, a charming independent theatre and a local cinema. There are a variety of excellent beaches to cater for all years to make the most of its glorious views. EPC Band D. tastes throughout the region whilst on your doorstep Lyme's beach and Cobb are a short stroll away for a spot of bathing, fishing or rock pooling. The area is designated as an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty and has excellent walking and riding out opportunities. 1 Sidmouth road is a convenient 6 miles away from the mainline station at Axminster with services to London Waterloo, making the area an ideal weekend or holiday retreat with excellent road and rail access further westwards into Devon and Cornwall. -

St Michael's House, 7 Pound Street

St Michael’s House, 7 Pound Street Graham Davies and Richard Wells May 2020 The house is set back from the roadside and adjacent properties on the Pound Street hill in Lyme Regis. Of Regency origin, the house underwent a Victorian makeover followed by further changes in the 20th/21st centuries. Initially a private house for almost a hundred years it became an hotel for most of the 20th century before being converted into flats in 2004. The Rev Michael Babbs bought the house in 1818. Did he name the house Mount Nebo or was it the earlier owner and/or builder? 2018 The Rev Babbs (1743-1831) came from London to Lyme Regis as a curate in 1792. He was accompanied by his daughters, Elizabeth and Mary Ann, and their step-mother, his second wife Mary. He rented the recently built house, Belle Vue (today’s Kersbrook), in Pound Road from Samuel Coade and was tenant there for the next 30 years. He served under four different vicars and seemed content to act as a perpetual curate at the Parish Church of St Michael the Archangel. He was a gentleman of additional means. The parish records show him to be a very busy clergyman, well known, not only in society, but to all classes of people in the community. He was described by his sexton, John Upjohn, as ‘a nice gentleman who wrote like copperplate’. It is not known when the house was built, by whom, and from whom it was purchased in 1818. Annotated survey What is known: 1. -

Ash Tree Disease Is Here First It Was Called Chalara Fraxinea, and Shows Many Healthy Mature Trees Then Science Showed It Was Just One Stage Will Eventually Succumb

BeneathSupported by the Upper Marshwood theVale Vale Parish Council Autumn 2019: Issue 33 Parish council chairperson Matthew Bowditch examines affected trees in Little Giant Wood in Stoke Abbott. Ash tree disease is here First it was called Chalara fraxinea, and shows many healthy mature trees then science showed it was just one stage will eventually succumb. Spores are of a fungus, Hymenoscyphus fraxineus, released from fruiting bodies and can so the name was changed. Gardeners be wind-spread for tens of kilometres. know Fraxinus as the ash, so this is now First noted in Polish forests, it was first the proper name of a very serious threat recorded in our lands in 2012, prompting to UK’s countyside – ash dieback. Worse, swift action by the authorities; sadly it is here now, spread through our Vale. even this was too late. A fungal infection, it affects young trees Parish council chairperson Matthew most of all, but European experience Bowditch showed us examples of ash Marshwood, Stoke Abbott, Pilsdon and Bettiscombe Contents Pothole party - the ‘hole’ truth page 4 Parish council meeting report for July page 5 Parish council meeting report for September page 7 Recipe: peppermint slices page 8 Local bus timetable updates page 10 Parish contacts page 12 Council trust funds page 15 Beneath the Vale is published four times a year with support from the Upper Marshwood Vale Parish Council and posted to homes in the combined parishes of Marshwood, Stoke Abbott, Pilsdon and Bettiscombe. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the parish council and advertising in the magazine does not imply council endorsement of any goods or services. -

Dorset Seasearch: Annual Summary Report 2017

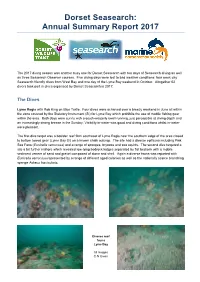

Dorset Seasearch: Annual Summary Report 2017 The 2017 diving season was another busy one for Dorset Seasearch with ten days of Seasearch diving as well as three Seasearch Observer courses. Five diving days were lost to bad weather conditions: four week day Seasearch friendly dives from West Bay and one day of the Lyme Bay weekend in October. Altogether 52 divers took part in dives organised by Dorset Seasearch in 2017. The Dives Lyme Regis with Rob King on Blue Turtle. Four dives were achieved over a breezy weekend in June all within the zone covered by the Statutory Instrument (SI) for Lyme Bay which prohibits the use of mobile fishing gear within the area. Both days were sunny with a south-westerly swell running, just perceptible at diving depth and an increasingly strong breeze in the Sunday. Visibility in-water was good and diving conditions whilst in-water were pleasant. The first dive target was a boulder reef 9km southeast of Lyme Regis near the southern edge of the area closed to bottom towed gear (Lyme Bay SI) on a known chalk outcrop. The site had a diverse epifauna including Pink Sea Fans (Eunicella verrucosa) and a range of sponges, bryozoa and sea squirts. The second dive targeted a site a bit further inshore which revealed low-lying bedrock ledges separated by flat bedrock with a mobile sediment veneer of sand and gravel composed of stone and shell. Again a diverse fauna was reported with Eunicella verrucosa represented by a range of different aged colonies as well as the nationally scarce branching sponge Adreus fascicularis. -

Jurassic Coast Fossil Acquisition Strategy Consultation Report

Jurassic Coast World Heritage Site Fossil acquisition strategy for the Jurassic Coast- Consultation Document A study to identify ways to safeguard important scientific fossils from the Dorset and East Devon Coast World Heritage Site – prepared by Weightman Associates and Hidden Horizons on behalf of the Jurassic Coast Team, Dorset County Council p Jurassic Coast World Heritage Site Fossil acquisition strategy for the Jurassic Coast CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………………………………2 2. BACKGROUND…………………………………………………………………………………..2 3. SPECIFIC ISSUES………………………………………..……………………………………….5 4. CONSULTATION WITH STAKEHOLDERS………………………………………………5 5. DISCUSSION……………………………………………………………………………………..11 6. CONCLUSIONS…………………………..……………………………………………………..14 7. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS…………………………………………………………………....14 8. APPENDIX..……………………………………………………………………………………...14 1 JURASSIC COAST FOSSIL ACQUISITION STRATEGY 1. Introduction The aim of this project is to identify ways to safeguard important scientific fossils from the Dorset and East Devon Coast World Heritage Site. The identification of placements in accredited museums would enable intellectual access for scientific study and education. Two consulting companies Weightman Associates and Hidden Horizons have been commissioned to undertake this Project. Weightman Associates is a partnership of Gill Weightman and Alan Weightman; they have been in partnership for twenty years working on museum and geology projects. Hidden Horizons Ltd is a museum and heritage consultancy formed in 2013 by Will Watts. When UNESCO granted World Heritage status to the Dorset and East Devon Coast in 2001 it recognised the importance of the Site’s geology and geomorphology. The Jurassic Coast Management Plan 2014-2019 has as one of its aims to “To Conserve and enhance the Site and its setting for science, education and public enjoyment” and the Plan states that a critical success factor is “An increase in the number of scientifically important fossils found along the site that are acquired by or loaned back to local accredited museums”. -

Lyme Bay 21St Meeting Minutes

Lyme Bay Fisheries and Conservation Reserve Consultative Committee Meeting Meeting held at the Royal Lion Hotel, Lyme Regis on 25th March 2014 Minutes of the meeting Present: Tim Glover, Blue Marine Foundation (Chair) Charles Clover, Blue Marine Foundation Neville Copperthwaite, Project Coordinator/Committee Secretary Kate West, Blue Marine Foundation Nick Wright, MMO Rachel Irish, MMO Sam Dell, Southern IFCA Lizy Gardner, Natural England Adam Rees, Plymouth University Professor Martin Attrill, Plymouth University Gus Caslake, Seafish Tom Rossiter, Succorfish Erin Priddle, EDF Matilda Bark, Dorset Coast Forum Mike Green, Beer representative. John Worswick –West Bay, scallop diver Dave Sales, Fisherman, West Bay, static gear Angus Walker, Fisherman, Axmouth, static gear Alex Jones, Fisherman, Lyme Regis, static gear Dave Hancock, Fisherman, Axmouth, static gear Aubrey Banfield, West Bay, static gear Nigel Hill, Fisherman, Lyme Regis, static gear Mike Spiller, Angling Trust. Jamie Smith, West Bay, static gear Note: Three representatives of the leisure diving industry were present: Sean Webb, Wreck to Reef Marcus Darler, O’Three Dry Suits Sarah Payne, Scimitar Diving Page 1 of 6 1) Apologies: Tim Robbins, Devon and Severn IFCA. Simon Pengelly, Southern IFCA Fiona Wheatley, Marks and Spencer Andy Woolmer, Fishery Adviser Liam McAleese, Marine Planning Consultants Jerry Percy, NUTFA Mark Machin – Samways Rowena Taylor, Graphic Designer Jim Newton, Beer Fisherman Bridget Betts, Dorset Coast Forum Paul Wason, Lyme Regis, towed gear Michael Coyle, Marine Management Organisation. Mark Cornwell, West Bay towed gear. Jim Portus, SWIFA. 2) Agree minutes of the 20th Working Group meeting: The minutes were agreed. 3) Update on Implementation of Management Plan a) Potting Study It was reported that the winter storms had taken its toll on the potting study gear and a total of 53 pots had been lost as well as all the no-fishing area marker dan-buoys. -

Dorsetshjre. Bridport

DIRECTORY.] DORSETSHJRE. BRIDPORT. 47 Councillors. Sanctuary Campbell Fortescue Stapleton esq. Manger· North Ward. South Ward. ton, Melplash 1 Pre,iding Alderman at Ward Presiding Alderman at Ward ~andwich The Earl of K.C.V.O. H?ok court, Beam~nster Electwns, T. A. Colfox Elections,Jo3eph '1'. Stephens Stephens Joseph Thompson e~q. Wanderwell ho.Bndport Retire Nov. Igu.. Retire Nov 1 I Udal John Symonds esq. Antigua, Leeward Islands Thomas Day Thomas C. Budde~ I. Weld Humphrey Frederick Joseph esq. Chideoc~, Bridprt John W. Houn•ell Harr N Cox Woodroffe Alban James esq. Ware, Lyme Regis John Suttill A d ~w S ·nE' The Mayors of Bridport & Lyme Regis & the Chair- • Retire Nov. 19r2 n r Retif: N~v. rgr2. n:en of the B:idport. & Beaminste~ ~ural District Coun- W. G. F. Cornick James Abbott Cils, for the t1me bemg, are ex-offiCio magistrates Henry H. Hounsell William S. Edwards Clerk to the Magistrates, Charles George Nantes, 36 George W. Read John 0. Palmer East street, Bridport Retire Nov. 1913. Retire Nov. 1913. Petty Sessions are held every alternate month on mon- William E. Bates Sidney R. Edwards day at the Town Hall, at 11 a.m. The following places John Blarney Al~e~t Norman are included in the Petty Sessional Division :-Alling- Arthur E. Champ Wllham J. G. West ton, Askerswell, Beaminster, Bradpole, Burstock, Mayor's Auditor, Arthur Edwin Champ Broadwindsor, Bettiscombe, Bothenhampton, Burton Elective Auditors, Samuel White & Stephen Ackerman Bradstock, Cheddington, Corscombe. Chelborough East & West, Chilcombe, Chideock, Charmouth, Catherston Officers of the Corporation. Leweston, Hook, Halstock, Loders, Lyme Regis, Map 1'own Clerk & Clerk to the Cemetery, Charles George perton, Mosterton, Marshwood.