The Olympic Games and New Sport, Recreation and Leisure Spaces for the Local Community

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Breakfast, Lunch, Dinner) After Breakfast Full Day City Tour of Istanbul Visiting;

7 Days 5 Nights The West & East (2 to go) Athens – 4 Days 3 Nights Day 1 ARRIVAL: Meet at Athens airport and transfer to hotel. Remainder of day at leisure. Athens is an amazing city to discover on your own with its numerous museums, parks, and the shopping areas of Kolonaki, Hermou, Voukourestiou Street, Monastiraki and Plaka. Overnight in Athens Hotel. Day 2 ATHENS SIGHTSEEING: (Breakfast) After breakfast, pickup from the hotel for your Half Day morning tour. See Syntagma Square, the House of Parliament, the Memorial to the Unknown Soldier, the Breakfast National Library, see the Hadrian’s Arch, visit the Temple of Olympian Zeus, the Panathenaic Stadium where the first Olympic Games of the modern era were held in 1896. On the Acropolis visit the architectural masterpieces of the Golden Age of Athens: the Propylaea, the Temple of Athena Nike, the Erectheion and finally “the harmony between material and spirit”, the Parthenon. Continue and visit the place where at last the statues found their home and admire the wonders of the classical era, the new museum of Acropolis (Mondays closed). Remainder of the day at leisure. Overnight in Athens Hotel. Day 3 ATHENS: (Breakfast) Breakfast in the hotel. Full day at leisure (free and easy) or, take an optional tour such as one day cruise Hydra-Poros-Aegina (including lunch). Breakfast Overnight in Athens Hotel. Day 4 DEPARTURE: (Breakfast) Transfer to the airport and proceed to Istanbul, Turkey. Breakfast 7 Days 5 Nights The West & East (2 to go) Istanbul – 3 Days 2 Nights Day 5 ARRIVAL ISTANBUL (Dinner) Arrival Istanbul and meet and assist at the airport. -

Travel Dates

GROUP TRAVELING: TRAVEL DATES: DAY 1 – TRAVEL DAY DAY 2 – PARLIAMENT SQUARE / NATIONAL ARCHEOLOGICAL MUSEUM / MT. LYCABETTUS • After meeting your JE Guide at the airport, you will transfer by coach to your hotel. • Parliament Building & Changing of the Guard • National Archeological Museum • Dinner Tonight your group may opt for an evening stroll up Mount Lycabettus for a great view of Athens! DAY 3 – AREOPAGUS HILL / ANCIENT AGORA / ACROPOLIS / LOCAL MARKET • Breakfast • Areopagus Hill (Mars Hill) • Ancient Agora • Lunch • Acropolis: Temple of Athena, Parthenon, Theatre of Dionysus, and Odeon of Herodes Atticus • Shopping at the Monastiraki Flea Market or The Central Market • Dinner * Tonight your group may opt to return to the Agora area for a night view of the Acropolis! DAY 4 – ATTEND A LOCAL CHURCH / PLAKA DISTRICT / TEMPLE OF OLYMPIAN ZEUS AREA • Breakfast • Attend a local church • Lunch • Arch of Hadrian, the ruins of the Temple of Olympian Zeus, and the site of the first modern Olympic Games. • Panathenaic Stadium • Shopping in the Plaka district Joshua Expeditions | (888) 341-7888 | joshuaexpeditions.org ©Joshua Expeditions. All rights reserved. GROUP TRAVELING: TRAVEL DATES: • Dinner* * Tonight your group may opt to attend a traditional dance or theater performance – ask for prices! DAY 5 – DAY TRIP (Select when requesting quote) • OPTION 1: • Ancient Corinth & Loutra Oraias Elenis (A beach, named after its most famous visitor, Helen of Troy!) • OPTION 2: • Greek Island Day Cruise DAY 6: TRAVEL DAY STAY LONGER? • Add 2-3 days, and visit the famous Meteora Monastery region, Thessaloniki, or do a Greek Islands Cruise! Interested in this trip experience? Contact our Travel Specialist today! (888) 341-7888 | joshuaexpeditions.org Joshua Expeditions | (888) 341-7888 | joshuaexpeditions.org ©Joshua Expeditions. -

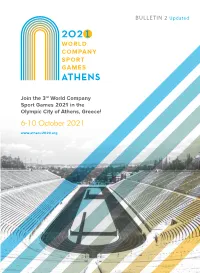

6-10 October 2021

BULLETIN 2 Updated 2021 6-10 October 2021 1 The Games CONTENTS 3rd WORLD COMPANY SPORT GAMES THE GAMES 3 We are proud to host the third edition of the World Company Sport Games that will take place in Athens, Greece from 6 to 10 October 2021! FOREWORD 4 The Company Sport’s heart will be beating in Athens uniting companies and people from 5 continents, demonstrating in the process the beneficial effects of company sport, whilst WFCS 6 carrying a strong message to the whole world: HOCSH 7 “Company sport is not just a sport event: It’s a need!” Following two successful editions of the World Company Sport Games in 2016 and 2018, SPORT DISCIPLINES 8 in Palma de Mallorca and La Baule respectively that welcomed thousands of athletes from across the world, Athens is ready to welcome back companies and competitors that take VENUES 18 part repeatedly in the games and inspire new ones to also participate in this vibrant event. WEBSITE & SOCIAL MEDIA 27 28 SPORT DISCIPLINES IN OLYMPIC VENUES EVENTS 28 The Olympic Athletic Center of Athens – O.A.K.A., the Official Sports Venue of the Olympic Games 2004, will proudly host the World Company Sport Games 2021! Participants will have the GREECE 32 opportunity to compete at the unique facilities of the Olympic Athletic Center of Athens and at other specially selected athletic venues. PARTICIPATION INFORMATION 38 The Organizing Committee of the 3rd World Company Sport Games will host the Opening Ceremony in the “Panathenaic Stadium”, the historical stadium that hosted the first modern HYGIENE PROTOCOL 39 Olympic Games in Athens 1896, providing a unique experience to the participants. -

6 Ways Experience More of Greece

6 Ways � Experience Corfu, Greece Corfu, More Of Greece. DIVE DEEPER INTO THE GREEK ISLES WITH A COUNTRY-INTENSIVE VOYAGE. While some cruise lines might simply add a couple of Greek ports to their itineraries, spending only a few hours in each, Azamara takes a different approach. We’re all about staying longer and experiencing more. So, what’s the best way to experience more of Greece? Sailing on board a country-intensive voyage. These cruises focus solely on one country, helping passengers truly immerse themselves in the destination with visits to smaller, less-visited ports and engaging in authentic experiences on land. To help you plan your next Mediterranean vacation, we’ve rounded up our six must-have experiences while exploring the Greek Isles. 3. SHOP FOR AUTHENTIC MEMENTOS 1. DISCOVER MORE BY ISLAND When packing for your cruise, be sure to leave HOPPING a little suitcase space for mementos. Greece Home to over 6,000 islands and islets dotting is renowned for its great shopping, and we’re the Aegean and Ionian Seas, of which only giving you the insider’s scoop on where to find 227 are inhabited, Greece is all about island- authentic pieces you can’t find elsewhere. hopping. There’s no question about it, the best way to soak it all in is by sailing on board a In Athens, you can visit designer boutiques cruise. in the trendy Kolonaki neighborhood, while Gulf of Corinth, Greece Corinth, Gulf of the Monastiraki neighborhood caters more to 2. TASTE THE AUTHENTIC FLAVORS vintage, artsy, and bohemian styles. -

Discover Athens, Greece Top 5

Discover Athens, Greece Photo: Anastasios71/Shutterstock.com Of all Europe’s historical capitals, Athens is probably the one that has changed the most in recent years. But even though it has become a modern metropolis, it still retains a good deal of its old small town feel. Here antiquity meets the future, and the ancient monuments mix with a trendier Athens and it is precisely these great contrasts that make the city such a fascinating place to explore.The heart of its historical centre is the Plaka neighbourhood, with narrow streets mingling like a labyrinth where to discover ancient secrets. Anastasios71/Shutterstock.com Top 5 1. Roman Agora During the antiquity, the Agora played a major role as both a marketplace and … 2. National Archaeological Museum The National Archaeological Museum, in Exarchia, is home to 3. The Acropolis and its surround The Parthenon, the temple of Athena, is the major city attraction as well as... Anastasios71/Shutterstock.com 4. Benaki Museum of Greek Culture Benaki is a history museum with Greek art and objects from the 5. Mount Lycabettus Mount Lycabettus (in Greek: Lykavittos, Λυκαβηττός) lies right in the centre... Milan Gonda/Shutterstock.com Athens THE CITY DO & SEE Nick Pavlakis/Shutterstock.com Anastasios71/Shutterstock.com Athens’ heyday was around 400 years BC, that’s Dive in perhaps the most historically rich capital when most of the classical monuments were of Europe and discover its secrets. Athens' past built. During the Byzantine and Turkish eras, the and its landmarks are worldly famous, but the city decayed into just an insignicant little city ofiers much more than the postcards show: village, only to become the capital of it is a vivid city of culture and art, where the newly-liberated Greece in 1833. -

Greece Pocket Travel Guide

W W W . O V E R P A C K E D S U IAT C A S Et. C O hM ens G R E E C E F POCKET TRAVEL GUIDE ACROPOLIS/PARTHENON O by Overpacked Suitcase ACROPOLIS MUSEUM ODEON OF HERODES ATTICUS OLD TEMPLE OF ATHENA C U R R E N C Y EURO (EUR €) PLAKA/ANAFIOTIKA NEIGHBOURHOOD T MONASTIRAKI Γεια σου TEMPLE OF HEPHAESTUS GREEK, ENGLISH IS S L A N G U A G E TEMPLE OF OLYMPIAN ZEUS WIDELY SPOKEN ANCIENT AGORA OF ATHENS E STOA OF ATTALOS HADRIAN'S LIBRARY V I S A S MOUNT LYCABETTUS - PERFECT FOR B SUNSET GREECE IS PART OF THE EUROPEAN UNION AND PART STREFI HILL OF THE SCHENGEN AREA. NO VISAS REQUIRED FOR ARCH OF HADRIAN PANATHENAIC STADIUM KERAMEIKOS MANY COUNTRIES, WITH A 90 DAY STAY ALLOWED ON FILOPAPPOU HILL ARRIVAL. PLEASE DOUBLE CHECK VISA PIRAEUS HARBOUR REQUIREMENTS BEFORE YOU TRAVEL AND MAKE SYNTAGMA SQUARE NATIONAL ARCHAEOLOGICAL MUSEUM SURE YOU HAVE THE CORRECT VISA. DAY TRIPS: SOUNIO DELPHI METEORA ANCIENT OLYMPIA M O N E Y ANCIENT CORINTH CREDITS CARD WIDELY ACCEPTED AND ATMS WIDELY EPIDAURUS ANCIENT THEATRE - (IF YOU GO DURING THE SUMMER YOU MIGHT EVEN BE AVAILABLE. SMALLER CAFES/TAKE AWAY FOOD PLACES ABLE TO CATCH A PLAY) AND ALSO GO FOR MAY ONLY TAKE CASH, BUT SHOULD "LEGALLY" ACCEPT A DIP IN THE SEA. CARDS TOO. NAFPLIO - PLAKA VIBES BETWEEN 5% AND 10%, BUT ALSO COMMON PRACTICE TO T I P P I N G LEAVE A FEW COINS TO ROUND UP THE BILL. -

Kyle Warwick Rebecca Daleiden Built: 330-329 BC Between 140 And

Kyle Warwick Rebecca Daleiden PANATHENAIC STADIUM Built: 330-329 BC Between 140 and 144 AD, Herodes Atticus restored and changed the Stadium Location: The stadium sits between the two hills of Agra and Ardettos, over the Ilissos river. Construction: This is a multi-purpose stadium used for several events and athletics in Originally this was a part of Athens that hosted the first modern Olympic Games in 1896. the natural ground. It was constructed into a stadium by Lykourgos in 330-329 BC for the athletic competitions of the Panathinaea Festivities. Lykourgos built the stadium that features a parallelogram shape with an entrance at one narrow end and room for the spectators on the earth slopes of the other three sides. Restorations that Herodes Atticus did: These restorations resulted in two main changes: the construction of the original rectilinear shape to a horseshoe shape and the installation of rows of seats of white marble. The track was 204,07 meters long and 33,35 meters wide. It is believed that the Stadium had a seating capacity of 50,000 people. Herodes possibly restored also the Ilissos river bridge on the Stadium's entrance. The Panathenaia: This was an Athenian festival celebrated every June in honor of the goddess Athena. The Lesser Panathenaia was an annual event, while the Greater was held every four years. Some of the events at the festival included: -The Musical Contest: This was only held at the Greater Panathenaea. The musical contest proper was introduced by Pericles, who built the new Odeum for the purpose. Previously the recitations of the rhapsodes were in the old unroofed Odeum. -

The Athens 1896 and Athens 1906 Olympic Pins

The Athens 1896 and Athens 1906 Olympic Pins By: Ioannis Thomakos The Athens 1896 and Athens 1906 Olympic Pins Revealing the first Pins in the History of the Olympic Games By: Ioannis Thomakos Ιn October 2018, I managed to publish a Book related to the Athens Games, with the title “Athens 2004 Olympic NOC Pins & Related Memorabilia, Vol. 1”. During the course of the preparation for this Book, I did extensive research on the History of Pins produced by National Olympic Committess from 1896 till today. The present article draws on this research. During preparations for the Athens 1896 Olympic Games the Greek Olympic Organising Committee decided among other things to decorate the main streets of Athens and the entrance of the Panathenaic Stadium with big banners carrying the flags and emblems of the participating nations. The Greek banner depicted the flag and national emblem of Greece (blue with white cross). These banners greatly enhanced the celebratory atmosphere in the city of Athens. Ιn February 1895 a very important meeting took place at the Zappeion Megaron, in Athens. It was chaired by crown Prince Constantin and was attended by all members of the Olympic Organising Committee. In that Special banners emblazoned with the flags and emblems of the participating nations meeting they decided to create nine sub-committees. Each was assigned decorated the main streets of Athens and the Panathenaic Stadium in 1896 and 1906. specific organising duties. They also elected their members. The first banner on the left depicts the flag and national emblem of Greece (blue with white Spyridon P. -

The Wines and Wonders of Greece

THE WINES AND WONDERS OF GREECE Explore Greece, a land of legends and myths on this once-in-a-lifetime, tailor-made journey hosted by Cooper’s Hawk Chef Matt McMillin. Join us as we dive into a culture alive with ancient history, passionate music, captivating arts, and intoxicating wines and cuisine. Wander through charming villages, seaside towns, renowned cities, and evocative temples. Meander through olive groves, vineyards, and museums and step into the stadium where Olympians fi rst competed. Dine at charming restaurants and embrace the fl avors of Greek wine and foods that are delicious, distinct, and diverse. Marvel at the endless shades of blue in the ocean and skies and the magnifi cence of dazzling sunsets. Th ere is limited space, so sign up now for this exceptional Wine Club tour and experience the splendor of Greece! SEPTEMBER 10 - 22, 2021 friday, september 10, 2021 DEPART USA Board your overnight fl ight from your home city. saturday, september 11, 2021 ARRIVE IN ATHENS, GREECE Welcome to Athens! A group transfer will be provided from the airport to your hotel (normal check-in times apply). Take some time to settle in, have lunch, and wander a bit. Tonight, we’ll join our Tour Director for an appetizing Greek-style 4-course dinner, including drinks, at a tavern in the festive Plaka district where folk dances put you in that special mood reminiscent of Zorba the Greek. Meals Included – Dinner Hotel – Hotel Zafolia or similar HIGHLIGHTS Welcome Dinner Plaka District WINE TRIP | GREECE sunday, september 12, 2021 EXCURSION TO CEFALÙ; ATHENS PALERMO TOUR After breakfast we’ll depart with our Tour Director and a Local Guide on a tour that features a visit to the world-famous Acropolis, perched high on a rocky outcrop overlooking the city. -

Greek Identity and the Olympic Games

GREEK IDENTITY AND THE OLYMPIC GAMES Part II Pierre de Frédy, Baron de Coubertin y A French historian and educator who revived the Olympic games at the end of 19th century. y He believed that sports education must be a significant part of young people’s personal development. y In 1894 together with DemitriosVikelas, Coubertin founded the International Olympic Committee. Pierre de Frédy, Baron de Coubertin y According to David Young, Professor of Classics at the University of Florida, Baron Pierre de Coubertin assiduously promoted himself as the lone force behind the Olympics - and deliberately obscured the contributions of Evangelos Zappas and a handful of other, now mostly forgotten Greek and British advocates for the games. y “He took an idea that others had been failing at, but working at for decades - he took that idea and claimed it as his own and made it work,” Young said. “The credit for the Olympics really goes to the good luck and hard work of several people.” Pierre de Frédy, Baron de Coubertin y “Coubertin was a very active sportsman and practiced the sports of boxing, fencing, horse-riding and rowing,” according to the committee’s Web site. “He was convinced that sport was the springboard for moral energy and he defended his idea with rare tenacity. It was this conviction that led him to announce at the age of 31 that he wanted to revive the Olympic Games.” y Yet the Games had been revived in Athens four year before he was born in 1859 by Evangelos Zappas. Evangelos Zappas y A Greek businessman, philanthropist and the real founder of the modern Olympic Games. -

The 1932 Los Angeles Olympics

THE 1932 LOS ANGELES OLYMPICS: A MODEL FOR A BROKEN SYSTEM By ROGER D. MOORE Bachelor of Arts in History Oklahoma State University Stillwater, OK 2012 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS May, 2015 THE 1932 LOS ANGELES OLYMPICS: A MODEL FOR A BROKEN SYSTEM Thesis Approved: Dr. Bill Bryans Thesis Adviser Dr. L.G. Moses Dr. Brian Frehner ii Name: ROGER D. MOORE Date of Degree: MAY, 2015 Title of Study: THE 1932 LOS ANGELES OLYMPICS: A MODEL FOR A BROKEN SYSTEM Major Field: HISTORY ABSTRACT: In discussion of Olympic Games and Los Angeles, 1984 is often the primary focus; but the Tenth Olympiad hosted by the same city in 1932 provides a more meaningful and lasting legacy within the Olympic narrative. This thesis looks at the stadium construction of Olympic host cities prior to 1932 and investigates the process by which Los Angeles came to host the 1932 Summer Olympics. The significance of the first athletic village and a history of the venues used for the 1932 competition will also be explored. This thesis will show that the depression-era 1932 Los Angeles Olympics provides a model more in line with original Olympic principals opposed to the current economically-driven system. Within that 1932 model is a means by which a host city can incorporate existing facilities adequate for a large festival and also, when and where construction is needed, provide future-use plans that serve a community beyond the duration of an Olympiad. -

View Brochure

AVA is a boutique hotel, offering some of the most spacious & self contained suites in Athens. A sanctuary for corporate and business travellers, who desire prime living conditions and conference facilities in the heart of Athens to combine business with pleasure. Our location in Plaka, the Historical Centre of Athens, gives you the opportunity to conduct your business and at the same time enjoy the Athens historical sites and museums as well as the unique ambiance of Plaka, with its traditional restaurants and its narrow cobbled streets. All few steps away from AVA. Feel the unique ambiance of Plaka, spoiled by AVA’s unique hospitality, comfortable suites & personalized care. AVA Conference Rooms can be customized in size and space (via sliding partitions) and can accommodate up to 80 people in a variety of arrangements (Theatre, U-Shape, Classroom, Boardroom). Our Conference Rooms include state-of-art presentation technology and equipment. Our experience and dedicated team guarantees a successful meeting. Conduct your important business whilst you enjoy the spaciousness, comfort & exclusiveness of our suites. Regular Suite Executive Suite AVA Exclusive Suite AVA Conference Rooms Floor Plan An exclusive location in Plaka, the fire historical centre of Athens, at the exit foot of the Acropolis. Fully equipped multi purpose room (max. 80 people) Business Centre Conference Room 1 4m • Ideal for Seminars, Workshops, Business Meetings and Events • Dedicated professional team • Exclusive Suites to relax and unwind • Customized packages for team building / socializing Conference Room 2 • Ergonomic chairs 5 m • Free high speed Wi-Fi internet • Hi-tech AV equipment sound system WC • LCD projector • Electrical screen 1.80 x 2.40 fire 5 m exit • Interactive Plasma Display HD Meeting Room or Reception • City highlights within walking distance WC ENTRANCE 8m AVA Hotel is situated in the Historical Centre of Athens, In the heart of picturesque Plaka, primarily an exclusive pedestrian area, known as the neighbourhood of Gods.