Use, Access, and Fire/Fuels Management Attitudes and Preferences of User Groups Concerning the Valles Caldera National Preserve (Vcnp) and Adjacent Areas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs by Title Karaoke Night with the Patman

Songs By Title Karaoke Night with the Patman Title Versions Title Versions 10 Years 3 Libras Wasteland SC Perfect Circle SI 10,000 Maniacs 3 Of Hearts Because The Night SC Love Is Enough SC Candy Everybody Wants DK 30 Seconds To Mars More Than This SC Kill SC These Are The Days SC 311 Trouble Me SC All Mixed Up SC 100 Proof Aged In Soul Don't Tread On Me SC Somebody's Been Sleeping SC Down SC 10CC Love Song SC I'm Not In Love DK You Wouldn't Believe SC Things We Do For Love SC 38 Special 112 Back Where You Belong SI Come See Me SC Caught Up In You SC Dance With Me SC Hold On Loosely AH It's Over Now SC If I'd Been The One SC Only You SC Rockin' Onto The Night SC Peaches And Cream SC Second Chance SC U Already Know SC Teacher, Teacher SC 12 Gauge Wild Eyed Southern Boys SC Dunkie Butt SC 3LW 1910 Fruitgum Co. No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) SC 1, 2, 3 Redlight SC 3T Simon Says DK Anything SC 1975 Tease Me SC The Sound SI 4 Non Blondes 2 Live Crew What's Up DK Doo Wah Diddy SC 4 P.M. Me So Horny SC Lay Down Your Love SC We Want Some Pussy SC Sukiyaki DK 2 Pac 4 Runner California Love (Original Version) SC Ripples SC Changes SC That Was Him SC Thugz Mansion SC 42nd Street 20 Fingers 42nd Street Song SC Short Dick Man SC We're In The Money SC 3 Doors Down 5 Seconds Of Summer Away From The Sun SC Amnesia SI Be Like That SC She Looks So Perfect SI Behind Those Eyes SC 5 Stairsteps Duck & Run SC Ooh Child SC Here By Me CB 50 Cent Here Without You CB Disco Inferno SC Kryptonite SC If I Can't SC Let Me Go SC In Da Club HT Live For Today SC P.I.M.P. -

Love Ain't Got No Color?

Sayaka Osanami Törngren LOVE AIN'T GOT NO COLOR? – Attitude toward interracial marriage in Sweden Föreliggande doktorsavhandling har producerats inom ramen för forskning och forskarutbildning vid REMESO, Institutionen för Samhälls- och Välfärdsstudier, Linköpings universitet. Samtidigt är den en produkt av forskningen vid IMER/MIM, Malmö högskola och det nära samarbetet mellan REMESO och IMER/MIM. Den publiceras i Linköping Studies in Arts and Science. Vid filosofiska fakulteten vid Linköpings universitet bedrivs forskning och ges forskarutbildning med utgångspunkt från breda problemområden. Forskningen är organiserad i mångvetenskapliga forskningsmiljöer och forskarutbildningen huvudsakligen i forskarskolor. Denna doktorsavhand- ling kommer från REMESO vid Institutionen för Samhälls- och Välfärdsstudier, Linköping Studies in Arts and Science No. 533, 2011. Vid IMER, Internationell Migration och Etniska Relationer, vid Malmö högskola bedrivs flervetenskaplig forskning utifrån ett antal breda huvudtema inom äm- nesområdet. IMER ger tillsammans med MIM, Malmö Institute for Studies of Migration, Diversity and Welfare, ut avhandlingsserien Malmö Studies in International Migration and Ethnic Relations. Denna avhandling är No 10 i avhandlingsserien. Distribueras av: REMESO, Institutionen för Samhälls- och Välfärsstudier, ISV Linköpings universitet, Norrköping SE-60174 Norrköping Sweden Internationell Migration och Etniska Relationer, IMER och Malmö Studies of Migration, Diversity and Welfare, MIM Malmö Högskola SE-205 06 Malmö, Sweden ISSN -

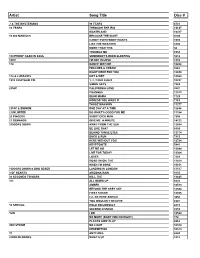

Copy UPDATED KAREOKE 2013

Artist Song Title Disc # ? & THE MYSTERIANS 96 TEARS 6781 10 YEARS THROUGH THE IRIS 13637 WASTELAND 13417 10,000 MANIACS BECAUSE THE NIGHT 9703 CANDY EVERYBODY WANTS 1693 LIKE THE WEATHER 6903 MORE THAN THIS 50 TROUBLE ME 6958 100 PROOF AGED IN SOUL SOMEBODY'S BEEN SLEEPING 5612 10CC I'M NOT IN LOVE 1910 112 DANCE WITH ME 10268 PEACHES & CREAM 9282 RIGHT HERE FOR YOU 12650 112 & LUDACRIS HOT & WET 12569 1910 FRUITGUM CO. 1, 2, 3 RED LIGHT 10237 SIMON SAYS 7083 2 PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE 3847 CHANGES 11513 DEAR MAMA 1729 HOW DO YOU WANT IT 7163 THUGZ MANSION 11277 2 PAC & EMINEM ONE DAY AT A TIME 12686 2 UNLIMITED DO WHAT'S GOOD FOR ME 11184 20 FINGERS SHORT DICK MAN 7505 21 DEMANDS GIVE ME A MINUTE 14122 3 DOORS DOWN AWAY FROM THE SUN 12664 BE LIKE THAT 8899 BEHIND THOSE EYES 13174 DUCK & RUN 7913 HERE WITHOUT YOU 12784 KRYPTONITE 5441 LET ME GO 13044 LIVE FOR TODAY 13364 LOSER 7609 ROAD I'M ON, THE 11419 WHEN I'M GONE 10651 3 DOORS DOWN & BOB SEGER LANDING IN LONDON 13517 3 OF HEARTS ARIZONA RAIN 9135 30 SECONDS TO MARS KILL, THE 13625 311 ALL MIXED UP 6641 AMBER 10513 BEYOND THE GREY SKY 12594 FIRST STRAW 12855 I'LL BE HERE AWHILE 9456 YOU WOULDN'T BELIEVE 8907 38 SPECIAL HOLD ON LOOSELY 2815 SECOND CHANCE 8559 3LW I DO 10524 NO MORE (BABY I'MA DO RIGHT) 178 PLAYAS GON' PLAY 8862 3RD STRIKE NO LIGHT 10310 REDEMPTION 10573 3T ANYTHING 6643 4 NON BLONDES WHAT'S UP 1412 4 P.M. -

Integrating Indigenous Knowledge Into an Undergraduate Earth Systems Science Course Mark H

Xoa:dau to Maunkaui: Integrating Indigenous Knowledge into an Undergraduate Earth Systems Science Course Mark H. Palmer1, R. Douglas Elmore2, Mary Jo Watson3, Kevin Kloesel4, Kristen Palmer5 ABSTRACT Very few Native American students pursue careers in the geosciences. To address this national problem, several units at the University of Oklahoma are implementing a geoscience “pipeline” program that is designed to increase the number of Native American students entering geoscience disciplines. One of the program’s strategies includes the development of an undergraduate course called ‘Earth Systems of the Southern Great Plains.’ The course focuses on geoscience topics that relate to the southern plains (particularly Oklahoma), emphasizes “sense of place,” integrates indigenous knowledge and geoscience content, makes use of Kiowa stories and metaphors, and uses Native American Art as a vehicle of learning. Students in the course are required to put living indigenous philosophies into practice through teaching activities and the construction of geoscience models using everyday materials. The course is designed to highlight the integrated nature of Earth processes, elicit students’ experiences through exploration of case studies illustrating links between indigenous knowledge and Earth processes, and demonstrate the process of practicing science. Formative student evaluations are providing useful information and the course is evolving. Preliminary assessment results suggest that integrating Native American culture, art, and geoscience content is a successful approach. INTRODUCTION communities, and contribute to the growing science and The course ‘Earth Systems on the Southern Great technology workforce in Oklahoma and surrounding Plains’ is an introductory Earth System Science course that regions. integrates indigenous knowledge into the geosciences and The introductory undergraduate course uses a uses Native American art as a vehicle of learning. -

Lloyd L. Lee Native American Studies 7-1-21

Lloyd L. Lee Native American Studies 7-1-21 Educational History Ph.D., 2004, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM, American Studies, Dissertation title: 21st Century Diné Cultural Identity: Defining and Practicing Sa’ah Naaghai Bik’eh Hozhoon, Amanda Cobb, Ph.D. M.A., 1995, Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA, Teacher Education and California Teaching Credential in Social Studies B.A., 1994, Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH, Major: History, Minor: Native American Studies Employment History, Part I Professor, 7/1/21 – present, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM Associate Professor, 7/1/14 – 6/30/21, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM Assistant Professor, 8/1/08 – 6/30/14, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM Assistant Professor, 8/1/04 – 7/31/07, Arizona State University, Phoenix, AZ Social Studies Teacher, 8/1/95 – 5/31/99, Wingate High School, Fort Wingate, NM Employment History Part II Visiting Assistant Professor in Native American Studies, 8/1/07 -7/31/08, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM Professional Recognition and Honors Presidential Teaching Fellow Award, promotes excellence in teaching and given the highest recognition for effective teaching, 2017 – 2019, Center for Teaching Excellence – University of New Mexico Honorary Stars, Special thank you and recognition from students, 2012 – 2013, American Indian Student Services – University of New Mexico Outstanding Commitment to Students Award, Recognition and honor of faculty and staff, 2005 -2006, Arizona State University at the West Campus 1 Short Narrative Description of Research, Teaching, and Service Interests My philosophy is to develop an individual’s critical consciousness through my teaching, research, and service. -

Songs by Title

Karaoke Song Book Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Nelly 18 And Life Skid Row #1 Crush Garbage 18 'til I Die Adams, Bryan #Dream Lennon, John 18 Yellow Roses Darin, Bobby (doo Wop) That Thing Parody 19 2000 Gorillaz (I Hate) Everything About You Three Days Grace 19 2000 Gorrilaz (I Would Do) Anything For Love Meatloaf 19 Somethin' Mark Wills (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here Twain, Shania 19 Somethin' Wills, Mark (I'm Not Your) Steppin' Stone Monkees, The 19 SOMETHING WILLS,MARK (Now & Then) There's A Fool Such As I Presley, Elvis 192000 Gorillaz (Our Love) Don't Throw It All Away Andy Gibb 1969 Stegall, Keith (Sitting On The) Dock Of The Bay Redding, Otis 1979 Smashing Pumpkins (Theme From) The Monkees Monkees, The 1982 Randy Travis (you Drive Me) Crazy Britney Spears 1982 Travis, Randy (Your Love Has Lifted Me) Higher And Higher Coolidge, Rita 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP '03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie And Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1999 Prince 1 2 3 Estefan, Gloria 1999 Prince & Revolution 1 Thing Amerie 1999 Wilkinsons, The 1, 2, 3, 4, Sumpin' New Coolio 19Th Nervous Breakdown Rolling Stones, The 1,2 STEP CIARA & M. ELLIOTT 2 Become 1 Jewel 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind 2 Become 1 Spice Girls 10 Min Sorry We've Stopped Taking Requests 2 Become 1 Spice Girls, The 10 Min The Karaoke Show Is Over 2 Become One SPICE GIRLS 10 Min Welcome To Karaoke Show 2 Faced Louise 10 Out Of 10 Louchie Lou 2 Find U Jewel 10 Rounds With Jose Cuervo Byrd, Tracy 2 For The Show Trooper 10 Seconds Down Sugar Ray 2 Legit 2 Quit Hammer, M.C. -

GARDENERGARDENER® Thethe Magazinemagazine Ofof Thethe Aamericanmerican Horticulturalhorticultural Societysociety July / August 2007

TheThe AmericanAmerican GARDENERGARDENER® TheThe MagazineMagazine ofof thethe AAmericanmerican HorticulturalHorticultural SocietySociety July / August 2007 pleasures of the Evening Garden HardyHardy PlantsPlants forfor Cold-ClimateCold-Climate RegionsRegions EveningEvening PrimrosesPrimroses DesigningDesigning withwith See-ThroughSee-Through PlantsPlants WIN THE BATTLE OF THE BULB The OXO GOOD GRIPS Quick-Release Bulb Planter features a heavy gauge steel shaft with a soft, comfortable, non-slip handle, large enough to accommodate two hands. The Planter’s patented Quick-Release lever replaces soil with a quick and easy squeeze. Dig in! 1.800.545.4411 www.oxo.com contents Volume 86, Number 4 . July / August 2007 FEATURES DEPARTMENTS 5 NOTES FROM RIVER FARM 6 MEMBERS’ FORUM 7 NEWS FROM AHS AHS award winners honored, President’s Council trip to Charlotte, fall plant and antiques sale at River Farm, America in Bloom Symposium in Arkansas, Eagle Scout project enhances River Farm garden, second AHS page 7 online plant seminar on annuals a success, page 39 Homestead in the Garden Weekend. 14 AHS PARTNERS IN PROFILE YourOutDoors, Inc. 16 PLEASURES OF THE EVENING GARDEN BY PETER LOEWER 44 ONE ON ONE WITH… Enjoy the garden after dark with appropriate design, good lighting, and the addition of fragrant, night-blooming plants. Steve Martino, landscape architect. 46 NATURAL CONNECTIONS 22 THE LEGEND OF HIDDEN Parasitic dodder. HOLLOW BY BOB HILL GARDENER’S NOTEBOOK Working beneath the radar, 48 Harald Neubauer is one of the Groundcovers that control weeds, meadow rues suited for northern gardens, new propagation wizards who online seed and fruit identification guide, keeps wholesale and retail national “Call Before You Dig” number nurseries stocked with the lat- established, saving wild magnolias, Union est woody plant selections. -

Transportation Inspiration Personal Experiences from Denmark, Sweden, and the Netherlands Bicycle Transportation Inspiration

bicycle transportation inspiration Personal experiences from Denmark, Sweden, and The Netherlands Bicycle Transportation Inspiration The reflections and insights in this publication are first-person accounts of the following students, who visited Denmark, Sweden, and The Netherlands to explore how cities can be improved to make cycling a more integral part of daily life. Daniel Chibbaro Rutgers University Samuel Copelan University of Oregon Sydney Herbst University of Oregon Holly Hixon University of Oregon Kirsten Jones University of Delaware Patrick Kelsey Tufts University Emily Kettell University of Oregon Christina Lane University of Oregon Kyle Meyer University of Oregon Jared Morford Iowa State University Heather Murphy University of Colorado Denver Olivia Offutt California State Polytechnic University, Pomona Hank Phan California State Polytechnic University, Pomona Myra Tetteh University of Michigan Emily Thomason Virginia Commonwealth University Bradley Tollison California State Polytechnic University, Pomona Jody Trendler University of Texas, Austin Xao Xiong University of Oregon Yazmin Valdez-Torres Florida State University Dr. Marc Schlossberg University of Oregon, Professor Adam Beecham Program Coordinator 2015 Bicycle Transportation Field Seminar hosted by the University of Oregon Bicycle Transportation Inspiration, copyright 2016 The Bicycle Transportation Planning Class There is something inexplicably happy-making about being on a bike, feeling safe and comfortable doing so, and being joined in the endeavor by thousands of others at all times of day in all locations in a city every day of the year. It is a feeling one can only get through experience, and if you want to have that feeling of freedom on a bike, visiting cities in Denmark and the Netherlands are a great way to go. -

East Asian and Western Perception of Nature in 20Th Century Painting

East Asian and Western Perception of Nature in 20th Century Painting Sungsil Park Ph.D. 2009 1 East Asian and Western Perception of Nature in 20th Century Painting Park Sung-Sil A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the University of Brighton for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy April 2009 University of Brighton 2 Abstract The introduction aims to investigate both my painting and exhibition practice, and the historical and theoretical issues raised by them. It also examines different views on nature by comparing and contrasting 20th Century Western ideas with those of traditional Asian art and philosophies. There are two sections to this thesis; Section A contains an historical overview of Eastern and Western philosophy and art, Section B presents observations on my studio and exhibition practice. Section A is divided into two chapters. Chapter 1 examines concepts of nature in the East and West before the early 20th Century. It discusses examples of different approaches to nature and cross-cultural world views and explores the diversity of perceptions, especially Taoism and Buddhism, which emphasize harmony within nature and the principle of universal truth. It also gives pertinent and relevant examples of attitudes to nature in the Korean, Chinese and Japanese art of the 20th Century. Chapter 2 discusses new and changing attitudes to ecology, post 20th Century, and the environmental art movements of the East and West. Their ideas have a great deal in common with traditional Eastern views on nature and the mind, so have the potential to change both our identity and our relationship with nature. -

James Blunt Giver Koncert På Rosenborg Slot

2011-03-08 07:13 CET James Blunt giver koncert på Rosenborg Slot Den britiske sanger og sangskriver gæster Rosenborg Slot den 16. Juni 2011. To albums, to verdens turneér og 18 millioner solgte plader senere har James Blunt været på en rejse som de færreste oplever. I november 2010 udgav han sit 3. studiealbum ”Some Kind of Trouble”, som i den første uge solgte over 1 million eksemplarer. Albummets første single hedder ”Stay the Night” og albummet indeholder mere optimistiske sange end tidligere, helt nøjagtigt 12 af slagsen og er produceret af Steve Robson. Det viser en Blunt med en ny følelse af spontanitet og friskhed – og ”Some Kind of Touble” er starten på et nyt kapitel. Folk forventer, at han er en meget seriøs person – der tager livet og sig selv alvorligt og det er slet ikke tilfældet. Han håber, at med dette album, folk vil se en anden side af ham. Hvert album har en milepæl som definerer en forfatter for sig selv. ”Goodbye My Lover” var milepælen på det første album og ”Same Mistake” var på album nr. 2. Sangen ”No Tears” er en usentimental ballade om ”opsummering af et liv” og den er Blunt´s milepæl på dette album. James Blunt er forhenværende soldat og var blandt andet udstationeret med de fredsbevarende styrker i Kosovo – men han valgte guitaren og musikken, hvilket nu har resulteret i rigtig mange hits. Han fik sit gennembrud i 2005 med singlen ”You´re Beautiful”, som er fra Blunt´s første album ”Back to Bedlam” – albummet indeholdt også sange som ”High” og føromtalte ”Goodbye My Lover” – sange som gjorde at James Blunt hittede overalt i verden. -

The Curtain Rises on a New Era for Broadway

$5.95 (U.S.), $6.95 (CAN.), £4.95 (U.K.), Y2,500 (JAPAN) 11.1..11,..1..1.11.1...1..11.1.111 I II In #BXNCCVR 3 -DIGIT 908 #90807GEE374EM002# BLED 780 A06 B0128 001 MAR 02 2 MONTY GREENLY 3740 ELM AVE # A LONG BEACH CA 90807 -3402 THE INTERNATIONAL NEWSWEEKLY OF MUSIC, VIDEO, AND HOME ENTERTAINMENT - APRIL 21, 2001 The Curtain Rises On A New Era For Broadway Atlantic Revives Musical Theater Gains fresh Creativity Even As Some Artists Struggle To Make Voices Heard Dance's Big Beat BY WAYNE HOFFMAN Rent seemed to offer Broadway Now that the dust has settled, ing a show, which makes investors BY MICHAEL PAOLETTA NEW YORK-Five years ago this a way out of the doldrums after insiders have divided opinions and wary of taking creative risks. NEW YORK -Two years ago, week, Rent hit Broadway like a years of declining box office and mixed emotions about the state of New composers are developing Big Beat Records stopped put- meteorite. A modern retelling of daring shows -but they often ting out product. Now, with the Puccini's La Bohème, Rent trans- find themselves consigned to off- imminent release of Plummet's ferred the setting to New York's Broadway or regional theaters. gritty East Village and translat- Record companies are releasing ed the opera into a rock -inspired cast albums from more unusual score. The musical, by a then - shows -but with almost no sup- unknown composer, filled its port from radio, they have trou- BIG stage with then -unheralded ble finding an audience. -

Students 2019

IF YOU DON’T WANT TO KEEP THIS ISSUE, RECYCLE IT. NYU’S TOP 10 INFLUENTIAL STUDENTS 2019 The Climate for Change These 10 students are redefining what environmentalism means both on campus and around the world. LETTER Jakiyah Bradley FROM THE EDITORS 04 06 Wayne Carino 08 Jon Chin 10 Devin James Gilmartin This year’s Influentials is a bit of the same and a bit of of organization and logistical planning, making the main something new. While the issue still contains 10 profiles photoshoot go as smoothly as possible — and the photos Omar Gowayed of incredible students making an impact at NYU, there’s are astounding. We also want to thank the rest of our multi a twist this time around. For the first time, we’ve added team who shadowed with our writers and took the great 12 a theme! This year’s Influentials issue is not just about a photos that grace our spread: Sam, Julia McNeill, Elaine set of influential people, but also a type of influence — Chen, Marva Shi, Ellie Ballou, Jorene He, Min Ji Kim, Chel- environmentalism. The issue is meant to analyze the ways sea Li and Sara Miranda. in which students are working to engage with environmen- This is also the first time we have produced additional tal issues and provide solutions while also giving insight content for an Influentials issue, which you will be able to into who each of these students are, as the leaders of find online. Traditionally Influentials has only included 10 tomorrow. profiles, but this year, we also have a series of features, cre- Maha Hashwi First, a huge thanks to our influential students: Winnie ative writing pieces and a stunning photo essay, allowing Xu, Carlos Martinez-Mejia, Heather Vaxer, Jon Chin, Devin us to take an expansive scope at tackling this theme.