Anabolic Steroids

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

By Exemestane, a Novel Irreversible Aromatase Inhibitor, in Postmenopausal Breast Cancer Patients1

Vol. 4, 2089-2093, September 1998 Clinical Cancer Research 2089 In Vivo Inhibition of Aromatization by Exemestane, a Novel Irreversible Aromatase Inhibitor, in Postmenopausal Breast Cancer Patients1 Jfirgen Geisler, Nick King, Gun Anker, ation aromatase inhibitor AG3 has been used for breast cancer Giorgio Ornati, Enrico Di Salle, treatment for more than two decades (1). Because of substantial side effects associated with AG treatment, several new aro- Per Eystein L#{248}nning,2 and Mitch Dowsett matase inhibitors have been introduced in clinical trials. Department of Oncology, Haukeland University Hospital, N-502l Aromatase inhibitors can be divided into two major classes Bergen, Norway [J. G., G. A., P. E. L.]; Academic Department of Biochemistry, Royal Marsden Hospital, London, SW3 6JJ, United of compounds, steroidal and nonsteroidal drugs. Nonsteroidal Kingdom [N. K., M. D.]; and Department of Experimental aromatase inhibitors include AG and the imidazole/triazole Endocrinology, Pharmacia and Upjohn, 20014 Nerviano, Italy [G. 0., compounds. With the exception of testololactone, a testosterone E. D. S.] derivative (2), steroidal aromatase inhibitors are all derivatives of A, the natural substrate for the aromatase enzyme (3). The second generation steroidal aromatase inhibitor, 4- ABSTRACT hydroxyandrostenedione (4-OHA, formestane), was found to The effect of exemestane (6-methylenandrosta-1,4- inhibit peripheral aromatization by -85% when administered diene-3,17-dione) 25 mg p.o. once daily on in vivo aromati- by the i.m. route at a dosage of 250 mg every 2 weeks as zation was studied in 10 postmenopausal women with ad- recommended (4) but only by 50-70% (5) when administered vanced breast cancer. -

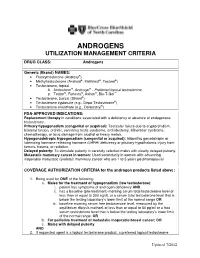

Androgens Utilization Management Criteria

ANDROGENS UTILIZATION MANAGEMENT CRITERIA DRUG CLASS: Androgens Generic (Brand) NAMES: • Fluoxymesterone (Androxy®) • Methyltestosterone (Android®, Methitest®, Testred®) • Testosterone, topical A. Androderm®, Androgel® - Preferred topical testosterone ® ® ® ™ B. Testim , Fortesta , Axiron , Bio-T-Gel • Testosterone, buccal (Striant®) • Testosterone cypionate (e.g., Depo-Testosterone®) • Testosterone enanthate (e.g., Delatestryl®) FDA-APPROVED INDICATIONS: Replacement therapy in conditions associated with a deficiency or absence of endogenous testosterone. Primary hypogonadism (congenital or acquired): Testicular failure due to cryptorchidism, bilateral torsion, orchitis, vanishing testis syndrome, orchidectomy, Klinefelter syndrome, chemotherapy, or toxic damage from alcohol or heavy metals. Hypogonadotropic hypogonadism (congenital or acquired): Idiopathic gonadotropin or luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH) deficiency or pituitary-hypothalamic injury from tumors, trauma, or radiation. Delayed puberty: To stimulate puberty in carefully selected males with clearly delayed puberty. Metastatic mammary cancer in women: Used secondarily in women with advancing inoperable metastatic (skeletal) mammary cancer who are 1 to 5 years postmenopausal COVERAGE AUTHORIZATION CRITERIA for the androgen products listed above: 1. Being used for ONE of the following: a. Males for the treatment of hypogonadism (low testosterone): i. patient has symptoms of androgen deficiency AND ii. has a baseline (pre-treatment) morning serum total testosterone level of less than or equal to 300 ng/dL or a serum total testosterone level that is below the testing laboratory’s lower limit of the normal range OR iii. baseline morning serum free testosterone level, measured by the equilibrium dialysis method, of less than or equal to 50 pg/ml or a free serum testosterone level that is below the testing laboratory’s lower limit of the normal range, OR b. -

Aromasin (Exemestane)

HIGHLIGHTS OF PRESCRIBING INFORMATION ------------------------------ADVERSE REACTIONS------------------------------ These highlights do not include all the information needed to use • Early breast cancer: Adverse reactions occurring in ≥10% of patients in AROMASIN safely and effectively. See full prescribing information for any treatment group (AROMASIN vs. tamoxifen) were hot flushes AROMASIN. (21.2% vs. 19.9%), fatigue (16.1% vs. 14.7%), arthralgia (14.6% vs. 8.6%), headache (13.1% vs. 10.8%), insomnia (12.4% vs. 8.9%), and AROMASIN® (exemestane) tablets, for oral use increased sweating (11.8% vs. 10.4%). Discontinuation rates due to AEs Initial U.S. Approval: 1999 were similar between AROMASIN and tamoxifen (6.3% vs. 5.1%). Incidences of cardiac ischemic events (myocardial infarction, angina, ----------------------------INDICATIONS AND USAGE--------------------------- and myocardial ischemia) were AROMASIN 1.6%, tamoxifen 0.6%. AROMASIN is an aromatase inhibitor indicated for: Incidence of cardiac failure: AROMASIN 0.4%, tamoxifen 0.3% (6, • adjuvant treatment of postmenopausal women with estrogen-receptor 6.1). positive early breast cancer who have received two to three years of • Advanced breast cancer: Most common adverse reactions were mild to tamoxifen and are switched to AROMASIN for completion of a total of moderate and included hot flushes (13% vs. 5%), nausea (9% vs. 5%), five consecutive years of adjuvant hormonal therapy (14.1). fatigue (8% vs. 10%), increased sweating (4% vs. 8%), and increased • treatment of advanced breast cancer in postmenopausal women whose appetite (3% vs. 6%) for AROMASIN and megestrol acetate, disease has progressed following tamoxifen therapy (14.2). respectively (6, 6.1). ----------------------DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION----------------------- To report SUSPECTED ADVERSE REACTIONS, contact Pfizer Inc at Recommended Dose: One 25 mg tablet once daily after a meal (2.1). -

CASODEX (Bicalutamide)

HIGHLIGHTS OF PRESCRIBING INFORMATION • Gynecomastia and breast pain have been reported during treatment with These highlights do not include all the information needed to use CASODEX 150 mg when used as a single agent. (5.3) CASODEX® safely and effectively. See full prescribing information for • CASODEX is used in combination with an LHRH agonist. LHRH CASODEX. agonists have been shown to cause a reduction in glucose tolerance in CASODEX® (bicalutamide) tablet, for oral use males. Consideration should be given to monitoring blood glucose in Initial U.S. Approval: 1995 patients receiving CASODEX in combination with LHRH agonists. (5.4) -------------------------- RECENT MAJOR CHANGES -------------------------- • Monitoring Prostate Specific Antigen (PSA) is recommended. Evaluate Warnings and Precautions (5.2) 10/2017 for clinical progression if PSA increases. (5.5) --------------------------- INDICATIONS AND USAGE -------------------------- ------------------------------ ADVERSE REACTIONS ----------------------------- • CASODEX 50 mg is an androgen receptor inhibitor indicated for use in Adverse reactions that occurred in more than 10% of patients receiving combination therapy with a luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone CASODEX plus an LHRH-A were: hot flashes, pain (including general, back, (LHRH) analog for the treatment of Stage D2 metastatic carcinoma of pelvic and abdominal), asthenia, constipation, infection, nausea, peripheral the prostate. (1) edema, dyspnea, diarrhea, hematuria, nocturia, and anemia. (6.1) • CASODEX 150 mg daily is not approved for use alone or with other treatments. (1) To report SUSPECTED ADVERSE REACTIONS, contact AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals LP at 1-800-236-9933 or FDA at 1-800-FDA-1088 or ---------------------- DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION ---------------------- www.fda.gov/medwatch The recommended dose for CASODEX therapy in combination with an LHRH analog is one 50 mg tablet once daily (morning or evening). -

Detectx® Serum 17Β-Estradiol Enzyme Immunoassay Kit

DetectX® Serum 17β-Estradiol Enzyme Immunoassay Kit 1 Plate Kit Catalog Number KB30-H1 5 Plate Kit Catalog Number KB30-H5 Species Independent Sample Types Validated: Multi-Species Serum and Plasma Please read this insert completely prior to using the product. For research use only. Not for use in diagnostic procedures. www.ArborAssays.com KB30-H WEB 210308 TABLE OF CONTENTS Background 3 Assay Principle 4 Related Products 4 Supplied Components 5 Storage Instructions 5 Other Materials Required 6 Precautions 6 Sample Types 7 Sample Preparation 7 Reagent Preparation 8 Assay Protocol 9 Calculation of Results 10 Typical Data 10-11 Validation Data Sensitivity, Linearity, etc. 11-13 Samples Values and Cross Reactivity 14 Warranty & Contact Information 15 Plate Layout Sheet 16 ® 2 EXPECT ASSAY ARTISTRY KB30-H WEB 210308 BACKGROUND 17β-Estradiol, C18H24O2, also known as E2 or oestradiol (1, 3, 5(10)-Estratrien-3, 17β-diol) is a key regulator of growth, differentiation, and function in a wide array of tissues, including the male and female reproductive tracts, mammary gland, brain, skeletal and cardiovascular systems. The predominant biological effects of E2 are mediated through two distinct intracellular receptors, ERα and ERβ, each encoded by unique genes possessing the functional domain characteristics of the steroid/thyroid hormone superfamily of nuclear receptors1. ERα is the predominant form expressed in the breast, uterus, cervix, and vagina. ERβ exhibits a more limited pattern and is primarily expressed in the ovary, prostate, testis, spleen, lung, hypothalamus, and thymus2. Estradiol also influences bone growth, brain development and maturation, and food intake3, and it is also critical in maintaining organ functions during severe trauma4,5. -

Cancer Palliative Care and Anabolic Therapies

Cancer Palliative Care and Anabolic Therapies Aminah Jatoi, M.D. Professor of Oncology Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota USA • 2 Androgens • Creatine • Comments von Haehling S, et al, 2017 Oxandrolone: androgen that causes less virilization oxandrolone RANDOMIZE megestrol acetate #1: Oxandrolone (Lesser, et al, ASCO abstract 9513; 2008) • N=155 patients receiving chemotherapy • oxandrolone (10 mg twice a day x 12 weeks) versus megestrol acetate (800 mg/day x 12 weeks) • oxandrolone led to – a non-statistically significant increase in lean body mass (bioelectrical impedance) at 12 weeks (2.67 versus 0.82 pounds with megestrol acetate, p = 0.12), but – a decrease in overall weight as compared with megestrol acetate (-3.3 versus +5.8 pounds, respectively). • more oxandrolone patients dropped out prior to completing 12 weeks (63% versus 39 %). #2: Oxandrolone (von Roenn, et al, ASCO, 2003) • N=131 • Single arm • 81% of patients gained/maintained weight • Safe (PRIMARY ENDPOINT): 19% edema; 18% dyspnea; mild liver function test abnormalities #3: Oxandrolone: placebo controlled trial • results unknown SUMMARY OF OXANDROLONE: • Multiple studies (not yet peer-reviewed) • Hints of augmentation of lean tissue • High drop out in the phase 3 oxandrolone arm raises concern Enobosarm: selective androgen receptor modulator (less virilizing) ENOBOSARM RANDOMIZE* PLACEBO *All patients had non-small cell lung cancer, and chemotherapy was given concomittantly. percentage of subjects at day 84 with stair climb power change >=10% from their baseline value percentage of subjects at day 84 with lean body mass change >=0% from their baseline value SUMMARY OF ENOBOSARM: • Leads to incremental lean body mass, but functionality not demonstrated • Pivotal registration trial (not yet peer- reviewed (but FDA-reviewed….)) • 2 Androgens • Creatine • Comments Creatine: an amino acid derivative This study was funded by R21CA098477 and the Alliance for Clinical Trials NCORP grant. -

A Guide to Feminizing Hormones – Estrogen

1 | Feminizing Hormones A Guide to Feminizing Hormones Hormone therapy is an option that can help transgender and gender-diverse people feel more comfortable in their bodies. Like other medical treatments, there are benefits and risks. Knowing what to expect will help us work together to maximize the benefits and minimize the risks. What are hormones? Hormones are chemical messengers that tell the body’s cells how to function, when to grow, when to divide, and when to die. They regulate many functions, including growth, sex drive, hunger, thirst, digestion, metabolism, fat burning & storage, blood sugar, cholesterol levels, and reproduction. What are sex hormones? Sex hormones regulate the development of sex characteristics, including the sex organs such as genitals and ovaries/testicles. Sex hormones also affect the secondary sex characteristics that typically develop at puberty, like facial and body hair, bone growth, breast growth, and voice changes. There are three categories of sex hormones in the body: • Androgens: testosterone, dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), dihydrotestosterone (DHT) • Estrogens: estradiol, estriol, estrone • Progestin: progesterone Generally, “males” tend to have higher androgen levels, and “females” tend to have higher levels of estrogens and progestogens. What is hormone therapy? Hormone therapy is taking medicine to change the levels of sex hormones in your body. Changing these levels will affect your hair growth, voice pitch, fat distribution, muscle mass, and other features associated with sex and gender. Feminizing hormone therapy can help make the body look and feel less “masculine” and more “feminine" — making your body more closely match your identity. What medicines are involved? There are different kinds of medicines used to change the levels of sex hormones in your body. -

COVID-19—The Potential Beneficial Therapeutic Effects of Spironolactone During SARS-Cov-2 Infection

pharmaceuticals Review COVID-19—The Potential Beneficial Therapeutic Effects of Spironolactone during SARS-CoV-2 Infection Katarzyna Kotfis 1,* , Kacper Lechowicz 1 , Sylwester Drozd˙ zal˙ 2 , Paulina Nied´zwiedzka-Rystwej 3 , Tomasz K. Wojdacz 4, Ewelina Grywalska 5 , Jowita Biernawska 6, Magda Wi´sniewska 7 and Miłosz Parczewski 8 1 Department of Anesthesiology, Intensive Therapy and Acute Intoxications, Pomeranian Medical University in Szczecin, 70-111 Szczecin, Poland; [email protected] 2 Department of Pharmacokinetics and Monitored Therapy, Pomeranian Medical University, 70-111 Szczecin, Poland; [email protected] 3 Institute of Biology, University of Szczecin, 71-412 Szczecin, Poland; [email protected] 4 Independent Clinical Epigenetics Laboratory, Pomeranian Medical University, 71-252 Szczecin, Poland; [email protected] 5 Department of Clinical Immunology and Immunotherapy, Medical University of Lublin, 20-093 Lublin, Poland; [email protected] 6 Department of Anesthesiology and Intensive Therapy, Pomeranian Medical University in Szczecin, 71-252 Szczecin, Poland; [email protected] 7 Clinical Department of Nephrology, Transplantology and Internal Medicine, Pomeranian Medical University, 70-111 Szczecin, Poland; [email protected] 8 Department of Infectious, Tropical Diseases and Immune Deficiency, Pomeranian Medical University in Szczecin, 71-455 Szczecin, Poland; [email protected] * Correspondence: katarzyna.kotfi[email protected]; Tel.: +48-91-466-11-44 Abstract: In March 2020, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by SARS-CoV-2 was declared Citation: Kotfis, K.; Lechowicz, K.; a global pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO). The clinical course of the disease is Drozd˙ zal,˙ S.; Nied´zwiedzka-Rystwej, unpredictable but may lead to severe acute respiratory infection (SARI) and pneumonia leading to P.; Wojdacz, T.K.; Grywalska, E.; acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). -

Hormonal Treatment Strategies Tailored to Non-Binary Transgender Individuals

Journal of Clinical Medicine Review Hormonal Treatment Strategies Tailored to Non-Binary Transgender Individuals Carlotta Cocchetti 1, Jiska Ristori 1, Alessia Romani 1, Mario Maggi 2 and Alessandra Daphne Fisher 1,* 1 Andrology, Women’s Endocrinology and Gender Incongruence Unit, Florence University Hospital, 50139 Florence, Italy; [email protected] (C.C); jiska.ristori@unifi.it (J.R.); [email protected] (A.R.) 2 Department of Experimental, Clinical and Biomedical Sciences, Careggi University Hospital, 50139 Florence, Italy; [email protected]fi.it * Correspondence: fi[email protected] Received: 16 April 2020; Accepted: 18 May 2020; Published: 26 May 2020 Abstract: Introduction: To date no standardized hormonal treatment protocols for non-binary transgender individuals have been described in the literature and there is a lack of data regarding their efficacy and safety. Objectives: To suggest possible treatment strategies for non-binary transgender individuals with non-standardized requests and to emphasize the importance of a personalized clinical approach. Methods: A narrative review of pertinent literature on gender-affirming hormonal treatment in transgender persons was performed using PubMed. Results: New hormonal treatment regimens outside those reported in current guidelines should be considered for non-binary transgender individuals, in order to improve psychological well-being and quality of life. In the present review we suggested the use of hormonal and non-hormonal compounds, which—based on their mechanism of action—could be used in these cases depending on clients’ requests. Conclusion: Requests for an individualized hormonal treatment in non-binary transgender individuals represent a future challenge for professionals managing transgender health care. For each case, clinicians should balance the benefits and risks of a personalized non-standardized treatment, actively involving the person in decisions regarding hormonal treatment. -

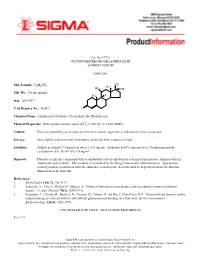

Fluoxymesterone-Dea Schedule Iii Androfluorene

Cat. No. F7751 FLUOXYMESTERONE--DEA SCHEDULE III ANDROFLUORENE Androgen. OH Mol. Formula: C20H29FO3 HO H3C CH3 Mol. Wt.: 336.45 (anhyd.) F H3C m.p.: 288-290°C CAS Registry No.: 76-43-7 O Chemical Name: 4-Androsten-9a-fluoro-17a-methyl-11b,17b-diol-3-one 22 Physical Properties: White photosensitive solid. [a] D = +102.34° (c = 0.47, EtOH). Caution: Due care should be exercised to prevent skin contact, ingestion or inhalation of this compound. Storage: Store tightly sealed at room temperature, protected from exposure to light. Solubility: Soluble in ethanol (7.3 mg/ml) or water (< 0.5 mg/ml). Solubility in 45% aqueous (w/v) 2-hydroxypropyl-b- cyclodextrin (Cat. No. H-107): 6.4 mg/ml. Disposal: Dissolve or mix the compound with a combustible solvent and burn in a chemical incinerator equipped with an afterburner and scrubber. This product is controlled by the Drug Enforcement Administration. Appropriate security must be maintained until the substance is destroyed. Records must be kept which detail the ultimate disposition of the material. References: 1. Merck Index 11th Ed., No. 4113. 2. Saborido, A., Vila, J., Molano, F., Megias, A. “Effect of steroids on mitochondria and sarcotubular system of skeletal muscle.” J. Appl. Physiol. 70(3), 1038 (1991). 3. Fernandez, L., Chirino, R., Boada, L.D., Navarro, D., Cabrera, N., del Rio, I., Diaz-Chico, B.N. “Stanozolol and danazol, unlike natural androgens, interact with the low affinity glucocorticoid-binding sites from male rat liver microsomes.” Endocrinology 134(3), 1401 (1994). CONTROLLED SUBSTANCE - DEA LICENSE REQUIRED (III) Rev. -

The In¯Uence of Medication on Erectile Function

International Journal of Impotence Research (1997) 9, 17±26 ß 1997 Stockton Press All rights reserved 0955-9930/97 $12.00 The in¯uence of medication on erectile function W Meinhardt1, RF Kropman2, P Vermeij3, AAB Lycklama aÁ Nijeholt4 and J Zwartendijk4 1Department of Urology, Netherlands Cancer Institute/Antoni van Leeuwenhoek Hospital, Plesmanlaan 121, 1066 CX Amsterdam, The Netherlands; 2Department of Urology, Leyenburg Hospital, Leyweg 275, 2545 CH The Hague, The Netherlands; 3Pharmacy; and 4Department of Urology, Leiden University Hospital, P.O. Box 9600, 2300 RC Leiden, The Netherlands Keywords: impotence; side-effect; antipsychotic; antihypertensive; physiology; erectile function Introduction stopped their antihypertensive treatment over a ®ve year period, because of side-effects on sexual function.5 In the drug registration procedures sexual Several physiological mechanisms are involved in function is not a major issue. This means that erectile function. A negative in¯uence of prescrip- knowledge of the problem is mainly dependent on tion-drugs on these mechanisms will not always case reports and the lists from side effect registries.6±8 come to the attention of the clinician, whereas a Another way of looking at the problem is drug causing priapism will rarely escape the atten- combining available data on mechanisms of action tion. of drugs with the knowledge of the physiological When erectile function is in¯uenced in a negative mechanisms involved in erectile function. The way compensation may occur. For example, age- advantage of this approach is that remedies may related penile sensory disorders may be compen- evolve from it. sated for by extra stimulation.1 Diminished in¯ux of In this paper we will discuss the subject in the blood will lead to a slower onset of the erection, but following order: may be accepted. -

Effects of Androgenic-Anabolic Steroids on Apolipoproteins and Lipoprotein (A) F Hartgens, G Rietjens, H a Keizer, H Kuipers, B H R Wolffenbuttel

253 Br J Sports Med: first published as 10.1136/bjsm.2003.000199 on 21 May 2004. Downloaded from ORIGINAL ARTICLE Effects of androgenic-anabolic steroids on apolipoproteins and lipoprotein (a) F Hartgens, G Rietjens, H A Keizer, H Kuipers, B H R Wolffenbuttel ............................................................................................................................... Br J Sports Med 2004;38:253–259. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2003.000199 Objectives: To investigate the effects of two different regimens of androgenic-anabolic steroid (AAS) administration on serum lipid and lipoproteins, and recovery of these variables after drug cessation, as indicators of the risk for cardiovascular disease in healthy male strength athletes. Methods: In a non-blinded study (study 1) serum lipoproteins and lipids were assessed in 19 subjects who self administered AASs for eight or 14 weeks, and in 16 non-using volunteers. In a randomised double blind, placebo controlled design, the effects of intramuscular administration of nandrolone decanoate (200 mg/week) for eight weeks on the same variables in 16 bodybuilders were studied (study 2). Fasting serum concentrations of total cholesterol, triglycerides, HDL-cholesterol (HDL-C), HDL2-cholesterol (HDL2- C), HDL3-cholesterol (HDL3-C), apolipoprotein A1 (Apo-A1), apolipoprotein B (Apo-B), and lipoprotein (a) (Lp(a)) were determined. Results: In study 1 AAS administration led to decreases in serum concentrations of HDL-C (from 1.08 (0.30) to 0.43 (0.22) mmol/l), HDL2-C (from 0.21 (0.18) to 0.05 (0.03) mmol/l), HDL3-C (from 0.87 (0.24) to 0.40 (0.20) mmol/l, and Apo-A1 (from 1.41 (0.27) to 0.71 (0.34) g/l), whereas Apo-B increased from 0.96 (0.13) to 1.32 (0.28) g/l.